In the 1940s and ‘50s, comic books were the scapegoat of choice for politicians, parents, and “experts” like Fredric Wertham, who sought something to blame for increasing juvenile delinquency and violence. Of course, that line of argument was cut short when the industry self-imposed the Comics Code Authority in 1954 and mainstream comics suddenly became much more upright and buttoned-down. For a few decades the older generations cast about for new scapegoats — rock & roll, the Pill — until they finally hit upon one with staying power: video games.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, comic books were the scapegoat of choice for politicians, parents, and “experts” like Fredric Wertham, who sought something to blame for increasing juvenile delinquency and violence. Of course, that line of argument was cut short when the industry self-imposed the Comics Code Authority in 1954 and mainstream comics suddenly became much more upright and buttoned-down. For a few decades the older generations cast about for new scapegoats — rock & roll, the Pill — until they finally hit upon one with staying power: video games.

In this month’s issue of Reason, Jesse Walker compiled “A Short History of Game Panics.” Many of them will be familiar to current gamers: Grand Theft Auto makes the list, as does the perpetual media-driven effort to connect video games to every mass shooting perpetrated by a young male from Columbine to Sandy Hook. But one section particularly stands out to us, as it reads like a template was lifted from the 1950s comic book panic and applied to video games in 1993. That was the year that then-Senator (and later vice presidential candidate) Joe Lieberman convened a Senate hearing on video games. “[V]iolence and violent images permeate more and more aspects of our lives, and I think it’s time to draw the line,” he said. “I know that one place where parents want us to draw the line is with violence in video games.”

Just as their predecessor Estes Kefauver did with comics in 1954, Lieberman and some of his colleagues highlighted the most salacious out-of-context snippets they could find from games like Mortal Kombat and the previously little-known Night Trap. In the latter case they entirely misunderstood the game’s objective, claiming that it was an “effort to trap and kill women” when in fact the player’s goal was to save the women from bloodsucking vampire-things.

And just as with comic book publishers like Bill Gaines at the 1954 hearings, the video game industry didn’t get anything close to a fair trial:

The senators kept grandstanding, the witnesses from Sega and Nintendo spent more time sniping at each other than defending their medium, and Sen. Herb Kohl (D-Wis.) issued a direct warning to the industry: ‘If you don’t do something about it, we will.’ Kohl and Lieberman underlined the threat a few months later, introducing a bill to impose government-run ratings on the industry if game makers didn’t adopt a satisfactory alternative themselves. That summer, the Entertainment Software Association duly announced a new ratings system.

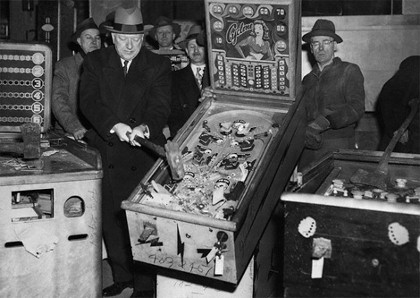

There’s an obvious parallel here to the founding of the Comics Code Authority, although a ratings system is a marginal improvement: At least games rated T and M can still be made (for now), while similar content in comics would have been verboten under the CCA. (Yes, there is an even more restrictive rating of AO for “Adults Only,” but it’s vanishingly rare and most major retailers won’t carry the games.) But even twenty years later, when the Senate’s concern over Mortal Kombat seems about as quaint as Fiorello LaGuardia’s 1942 crusade against pinball machines, politicians and the media are still hashing out this very same debate. One may hope that video games will gain some favor as those who grew up with them increasingly enter the halls of power — indeed, there’s already at least one hardcore gamer in Congress — but this repeating scenario suggests an unfortunate truth: Certain individuals will likely find some other new technology or format to take the blame for all that ails today’s youth.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.