Well over a month after a high school principal in Pensacola, Florida cancelled a summer reading program rather than allow students to read Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother, we finally heard this week from that principal’s boss, Escambia County School District Superintendent Malcolm Thomas. While Thomas admitted that Washington High School Principal Michael Roberts ignored or perhaps was not even aware of district policy on removing materials from the curriculum, he also gave no indication that the decision will be reconsidered.

Well over a month after a high school principal in Pensacola, Florida cancelled a summer reading program rather than allow students to read Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother, we finally heard this week from that principal’s boss, Escambia County School District Superintendent Malcolm Thomas. While Thomas admitted that Washington High School Principal Michael Roberts ignored or perhaps was not even aware of district policy on removing materials from the curriculum, he also gave no indication that the decision will be reconsidered.

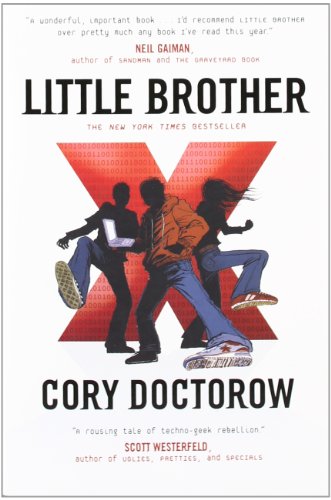

Roberts had previously approved Little Brother as a One Book/One School reading selection for the program organized by English teacher Mary Kate Griffith and librarian Betsy Woolley. After school was already dismissed for the summer, however, Roberts apparently took a closer look at reviews of the book and didn’t like what he found. According to Doctorow, he put the kibosh on the program with an email to Griffith:

[T]he principal cited reviews that emphasized the book’s positive view of questioning authority, lauding ‘hacker culture’, and discussing sex and sexuality in passing. He mentioned that a parent had complained about profanity (there’s no profanity in the book, though there’s a reference to a swear word). In short, he made it clear that the book was being challenged because of its politics and its content.

In local news coverage, meanwhile, Roberts claimed that “there has been no banning” — simply a removal of the book from 9th and 10th grade reading lists due to “language” and “overtures.” As CBLDF and other member organizations of the Kids’ Right to Read Project from the National Coalition Against Censorship pointed out at the time, Roberts should have directed any parent who had concerns about the book to submit a formal complaint as outlined in the district’s policy on challenged materials. The challenge would then be considered by a school-level review committee; if no agreement was reached there the issue could move up to a district-level review committee. But of course, all of that would take time and the challenged materials policy also says that “access to challenged resources shall not be restricted during the review process.” Based on Roberts’ own objections to the book’s themes cited above, it appears his goal was not to conscientiously address a parent’s complaint, but to immediately minimize the number of students reading the book. (We’re willing to bet that plan has backfired!)

In an article from the Pensacola News-Journal, Superintendent Thomas stopped short of naming Roberts when he said that “no one involved in that case communicated well, and they didn’t take advantage of the procedures available to them.” Thomas also managed to imply that English teacher Griffith did not provide alternate options for students or their parents who were uncomfortable with anything in Little Brother. Luckily, Griffith’s original summer reading assignment sheet is still online at Doctorow’s website, and that information is front and center:

Parents are the ultimate authority in deciding appropriate material for their children, so parents requesting an alternative assignment should contact Mrs. Griffith.

So when Thomas says that “no one involved…communicated well,” surely he only means Roberts. Besides, if he knew that district policy was being ignored, why did he not point it out at the time? Even at this late date, the best course of action would still be to reinstate the reading program, provide an alternate option to the one parent who complained, and send the book to a review committee if that parent still wishes to pursue a challenge.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.