Cows are natural comedians, as Far Side creator Gary Larson proved many times over the years. A great deal of the bovine potential for visual humor lies in their udders, and early animators from Disney and other studios quickly latched on (pun intended) in the late 1920s. But the udder party lasted only a few years before Hollywood censors decided that nude cows were not appropriate for the silver screen. Come with us on a strange trip through the history of animated cowdom.

Although other studios also used cows in their cartoons, the udder restrictions are most easily traced via Disney’s Clarabelle Cow. In her first few years, when she walked on four legs and wore only a cowbell, animators positively lavished attention on her pendulous udder. It was involved in numerous sight gags, and swung freely when she was in motion. The animation studios’ brief love affair with bovine mammaries was halted in February 1931, however, as reported by Time:

Motion Picture Producers & Distributors of America last week announced that, because of complaints of many censor boards, the famed udder of the cow in the Mickey Mouse cartoons was now banned. Cows in Mickey Mouse or other cartoon pictures in the future will have small or invisible udders quite unlike the gargantuan organ whose antics of late have shocked some and convulsed other of Mickey Mouse’s patrons.

Instead of suddenly making familiar cows’ udders “small or invisible,” though, most animators opted to clothe them. At first Clarabelle wore only a skirt and continued to walk on four legs, but her creators seemed to realize that looked odd and soon had her bipedal most of the time. (At that point she also sprouted three-fingered hands on her front legs rather than hooves.) Eventually the skirt became a full dress, and Clarabelle’s transformation from bovine to humanoid was complete. As with the oft-remarked Goofy-Pluto dichotomy, Disney animated shorts henceforth draw a distinction between Clarabelle and more cow-like cows, who walk on four legs and do not speak. In 1931’s “Mother Goose Melodies” there is even a humanoid skirt-wearing cow (not identified as Clarabelle) in the frame story and a floppy-uddered bovine cow–she who jumped over the moon–in one of the nursery rhyme sequences.

Although animators’ initial relish for udders seems to stem more from comedic instinct than from salaciousness, there is hardly any doubt that they took to taunting the censors once they began to receive complaints. In the case of Disney this is most evident in 1930’s “The Shindig,” where Clarabelle’s udder is given a last hurrah before being covered up forever. Alert readers will note that this cartoon actually predates the 1931 udder ban reported above, which applied to all U.S. studios; Disney apparently decided independently to clothe Clarabelle before then so as to assure maximum distribution of its films, since it was already taking criticism from individual state censorship boards and from other countries including Canada.

But first, the studio took a masterful parting shot at what it obviously considered ridiculous levels of prudery. When Clarabelle first appears onscreen in “The Shindig” she is alone in her boudoir/barn, contentedly chewing cud and reading a book called Three Weeks while resting on her ample udder. The inclusion of Three Weeks by Elinor Glyn is a joke that has sadly been lost to time, but adults of 1930 would have recognized it as a steamy romance novel that was quite literally “banned in Boston”–and in Canada. After that wink at would-be censors, Clarabelle’s beau Horace Horsecollar arrives to take her to a barn dance. “I’ll be out in a minute,” she warbles–and coyly steps behind a partition to don her skirt which had been hanging on the wall. Only then do viewers realize that according to the film’s internal logic, she was “naked” until that point! For good measure she also primly readjusts her skirt after hopping on the back of Horace’s motorcycle, to ensure that no hint of udder is showing.

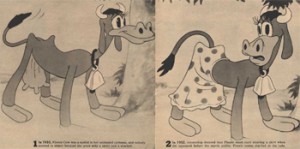

Ironically, “The Shindig” itself did end up banned in Ohio, supposedly only because of Three Weeks and not the suggestion of nudity. But in any case, Clarabelle’s udder made no more appearances on film–once animators had clothed her, they were no more likely to unclothe her than they would Minnie Mouse. The transition was rather more abrupt for the nameless cows of other studios, like the Warner Brothers bovine shown above in 1931 and 1932. Although the Hays Code–the Hollywood equivalent of and inspiration for the later Comics Code–was not fully enforced until 1934, the ban on ostentatious cartoon udders was widely reported in the press in 1931 and was apparently taken seriously by studios.

The end of udder prohibition seems to have come around 1941, when Donald Duck and a cow named Clementine starred in the milking extravaganza “Old MacDonald Duck.” Only a year earlier, the Hays Office had been ridiculed in the press for banning the udder of Elsie the Borden cow when she made a cameo in the live-action family feature Little Men. In September 1940, Hollywood columnist Jimmie Fidler reported mockingly:

Mr. Hays & Co….were busy saving American youth from utter catastrophe by banning shots–horrors, how can I bring myself to say it?–shots of the udders, the bare, undraped udders, of Elsie the cow! Yes, the Hays censors, in rightful indignation, were very busy ruling that scenes showing Elsie being milked must be taken from the side opposite the milker, so those naked udders could not be seen.

This is a time for compromise. I’m sure you’ll agree particularly those of you who live on farms and know the moral depravity that can result from [the] sight of an undressed cow–that we have been saved from a major disaster by the Hays office alertness.

Fidler’s rival at United Press, Frederick C. Othman, provided a detailed account of the reaction on the set of Little Men to the memo saying that udders should be “suggested, rather than shown.” Although the milking scene was key to the film’s plot, the Hays Office predicted it would be censored in certain localities if filmed as written. Wrote Othman:

These gentlemen [censors], particularly in Ohio, New York and the city of Chicago, have odd ideas about what is moral and what isn’t and the act of milking a cow, even if it’s Elsie, the most beautiful cow in the world, is something they will not allow their citizens to see upon the screen.

Director Norman McLeod, after some consternation as to “how in the Sam Hill…anyone expect[ed] him to suggest an udder,” eventually settled for focusing “the camera on Elsie’s placid face, so that her milk department would not actually show on the screen” as actress Kay Francis “made vague milking motions” near the hind end.

In light of this event, there is some question as to why Donald Duck was permitted only a year later to not only milk a cow, but gleefully use the contents of her udder to spray a pesky fly. All of Hollywood and a good part of the mainstream American public was most certainly aware of what happened on Little Men; did the Hays Office buckle under widespread ridicule? Was “Old MacDonald Duck” designed to test the boundaries? In any case Disney animation had by then transitioned to its signature naturalist style, and the exaggerated udders of the early years were no more–the animated Clementine’s udder was proportional to the real Elsie’s, if viewers had been allowed to see the latter.

Today the Hays Code has long since been replaced by the MPAA content ratings system, and film studios at least consider udders (on cows other than Clarabelle, who still appears occasionally in all types of Disney media) to be family friendly. Nevertheless, Disney has encountered viewer complaints about milking scenes and udder gags at least a few more times over the years. A review of 101 Dalmatians (1961), for instance, says that a scene in which the puppies on the run suckle from some kindly cows was “cut from some prints because the sight of teats was deemed offensive.” And the largely forgotten Home on the Range (2004) provoked mild backlash from parents who objected to a cow’s indignant description of her own mammaries: “Yes, they’re real!” The Hays Code’s repression arguably still echoes today in our culture’s warped relationship to milk glands–in more than one species.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.