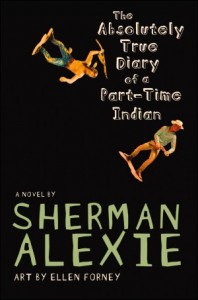

School district administrators and teachers in Waterloo, Iowa are currently locked in a debate as to whether Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian is appropriate for middle school classrooms. The district’s curriculum director sent an email ordering the book’s removal on March 13, but at least five teachers have pushed back, pointing out that the existing challenge policy has not been observed.

School district administrators and teachers in Waterloo, Iowa are currently locked in a debate as to whether Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian is appropriate for middle school classrooms. The district’s curriculum director sent an email ordering the book’s removal on March 13, but at least five teachers have pushed back, pointing out that the existing challenge policy has not been observed.

The district received a parent complaint about the book sometime last month, but instead of forming a review committee as the challenge policy clearly requires, curriculum director Debbie Lee simply sent an email to 60 teachers and other employees that read in part:

I am requiring all copies of the novel, ‘The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian’, be removed from our classroom booksets. This book is not appropriate for use as an instructional tool in our middle school classrooms.

When some teachers responding to the email directive pointed out that the challenge policy had been ignored, Lee initially argued that the parent’s complaint did not constitute a challenge at all, even though that’s precisely what it was. Superintendent Jane Lindaman also claimed that because she and Lee agreed with the parent’s complaint, “there was no need to file a request to remove the book.”

Lee and Lindaman’s statements evince a shameful and alarming failure to comprehend the entire point of having a challenge policy, let alone any policies at all. Policies exist in part to ensure that contentious situations are handled equitably and without favoritism or bias. If the two administrators agreed with the parent’s assessment of the book, that should have been a clue that they needed to seek input from the diverse group of experienced teachers, librarians, parents, and other administrators who would sit on a review committee. That process is designed precisely to avoid the danger of any one person exerting too much control other the district’s curriculum and library collections.

In the emails responding to the order to remove Absolutely True Diary, several middle school teachers disagreed with Lindaman’s view that the book is “inarguably inappropriate for such young minds.” Eighth grade literacy teacher Kevin Roberts noted that his advanced class had just finished reading the book, and “some students told him it was the only book they had ever read they actually liked.” The very fact that he and other teachers were arguing proved that the book is not “inarguably inappropriate,” he said, and thus the review procedure should be observed.

In the midst of the email debate with teachers, Lee also made a particularly worrying statement about curriculum design in general: “If you ask yourself if maybe a text might be controversial, then it probably is, so don’t use it.” Roberts strongly disagreed with that mindset, stating:

I ask if, as a district, we value discourse and the inclusion of professionals in the censoring process. I cannot support the guidelines for text selection laid out in Dr. Lee’s original email as they have a chilling effect on discourse and growth in the classroom as well as belittle the role of teachers as responsible decision makers.

As of Wednesday when the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier broke this story, Lee and Lindaman showed no inclination to reverse course and follow the challenge policy. To the contrary, in fact, Lindaman hinted she would prefer to change the policy itself, “adding language where needed to enhance clarity on the process for approving materials containing sexual references and profanity (i.e. who is involved, forms needing to be submitted).”

This story naturally calls to mind the 2013 removal of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis from classrooms in Chicago Public Schools. There as well, the ban was orchestrated by a few administrators who likely hadn’t read the entire book, but concluded based on a few excerpts that it was inappropriate for all students. Although many heroic CPS teachers and librarians quietly worked behind the scenes to make sure students could still read the book, sadly the atmosphere in that district is so repressive that few dared to protest the classroom ban directly. Judging by the lively debate that arose in response to Lee’s order, Waterloo Public Schools have not yet reached that point, but administrators should ask themselves if that’s really the direction they want to take. Another important difference between the two cases is that while Chicago does not have a challenge policy for classroom materials, Waterloo does. Administrators should follow it immediately, not just to make sure that free speech is defended, but also as a demonstration of good faith and respect for their teachers’ professional judgment.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.