In the modern popular imagination, the 1950s represent the height of repression, conformity, paranoia, and of course censorship. To be sure, the era did see the brief rise of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, the continued effects of the Hollywood blacklist (instituted in 1947), and the founding of the Comics Code Authority in order to stave off government regulation of comics. But a recent historical feature from the Jacksonville, Illinois Journal-Courier about a 1953 purge of “books of a salacious, vulgar or obscene character” from the state library’s collection shows that even at that time, the general public did not take kindly to censorship.

In the modern popular imagination, the 1950s represent the height of repression, conformity, paranoia, and of course censorship. To be sure, the era did see the brief rise of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, the continued effects of the Hollywood blacklist (instituted in 1947), and the founding of the Comics Code Authority in order to stave off government regulation of comics. But a recent historical feature from the Jacksonville, Illinois Journal-Courier about a 1953 purge of “books of a salacious, vulgar or obscene character” from the state library’s collection shows that even at that time, the general public did not take kindly to censorship.

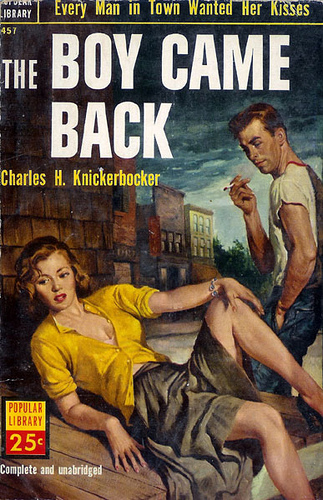

The story started with a state library program that distributed lending collections of books to rural schools that did not have their own libraries. That was how, in southern Illinois’ Richland County, a high school student wound up checking out a pulp novel called The Boy Came Back by Charles H. Knickerbocker. In his piece for the Journal-Courier, Illinois historian Tom Emery describes the plot:

The central characters were simply known as the Boy, an alcoholic, violent Army veteran, and his wife, the Girl, who is desired by most of the town’s married men. She is later murdered by her husband. Graphic sexual descriptions and profanity are frequent in the book, which received favorable reviews.

Scandalized, the mother of the teenaged girl who checked out the book turned it over to Richland County Sheriff Jesse Shipley, who then wrote a letter to Governor William Stratton urging that “the guilty persons [who purchased the book for the state library] be prosecuted and that the legislature conduct an inquiry into the matter.” Although The Boy Came Back was in fact targeted at an adult audience and library staff said it was only sent to the high school due to a clerical error, Shipley added that it “appeared to have a communistic intent of attempting to lower the morality of American boys and girls.”

Richland County school superintendent Loren W. Cammon also sent his own letter direct to the state library, describing the book thusly:

Without a doubt, it is the worst form of reading material I have ever seen in a high school. It is lewd in every sense of the word. I strenuously protest having such immoral reading material issued to the schools of Richland County.

In 1953 as today, the title of State Librarian in Illinois was held by the elected Secretary of State, who was unlikely to have any practical experience in library administration or much involvement in the day-to-day operations of the State Library in Springfield. Helene Rogers, the woman who actually did run the library, was technically the Assistant State Librarian. (Today the person who fills that role at least gets the title of Director.) Secretary of State Charles Carpentier publicly rebuked Rogers and ordered her to remove all “books of a salacious, vulgar or obscene character” from circulation.

Rogers subsequently comes out looking like a villain in this saga, but a strong argument can be made that her actions were in fact calculated to highlight the impractical (not to mention unconstitutional) nature of Carpentier’s directive. One clue: Before proceeding with the purge, Rogers wryly noted that “if we acted on [the order] as it stands we would start with the Bible.” Instead, she diligently set about removing any books that were not on a fiction core title list published by library industry vendor H.W. Wilson. Core title lists are valuable resources for building collections and ensuring broad coverage, but they are intended to be supplemented by librarians’ specialized knowledge of items in demand from their particular patron group.

In a little over a month, Rogers had pulled 400 titles, including works by popular authors such as Sinclair Lewis, John Dos Passos, and Mickey Spillane. Many of those titles had multiple copies in the library collection for statewide distribution, so the total number of volumes removed was between 6,000 and 8,000. But in mid-December Carpentier’s hometown newspaper the Moline Dispatch got wind of the story, which quickly spread nationally and even internationally. According to Emory, Illinoisans were none too happy with their sudden status as a universal laughing stock, and Stratton quickly realized his administration had miscalculated the public’s tolerance for censorship:

Public opinion swayed against the ban. The Dispatch quoted Mrs. Howard Riordan of Erie, who had to return one of her borrowed books, in calling the purge ‘a ridiculous gesture.’ Nervous political leaders scrambled to quiet the furor, and Gov. Stratton retreated from his original stance, now saying that child readers should be ‘protected’ while ‘the adult population can read what they want.’

Secretary of State Carpentier again laid the blame on Helene Rogers. A statement from his office said that “this overzealous and wholesale withdrawal of hundreds of books from general circulation goes far beyond protecting school children in the selection of reading material, and has the tendency of making his original intention appear ridiculous.” Indeed!

The Daily Illini student newspaper at the University of Illinois, home to a trailblazing library school that remains top-ranked to this day, published a short article on the reactions of faculty members who also happened to sit on the state library’s advisory committee. University library (and library school) director Robert B. Downs, later the namesake of an intellectual freedom award presented to CBLDF in 2010, stated that “I believe the directive should be withdrawn immediately.” Fellow committee member and associate professor of rural sociology Clinton L. Folse decried “witch hunting in the libraries.” (Incidentally, another hint that the 1950s were not quite as buttoned-up as we tend to imagine today lies two columns to the right, in the mainstream cinema ad for a French girls’-school movie released in the U.S. as The Sinners.)

On January 5, 1954, Carpentier issued another order to Rogers — this time, to restore all the books she had withdrawn including The Boy Came Back. But there was still a catch: Carpentier remained determined to “make it impossible for school children to obtain smut or objectionable materials from the Illinois State Library.” Certain books were therefore stamped with the enticing notice “this book is for adult readers.” Even then, Carpentier still couldn’t win in the eyes of the international press, says Emory:

The stamping process itself only inflamed the controversy. Over 500 newspapers in Great Britain carried news of the book stamping, one writing that ‘they are not burning books in the state of Illinois, they are putting “red flags” on them.’ On Feb. 6, Carpentier wearily admitted that the book-banning ‘had turned into a comedy of errors … I’m ready to climb the walls over this thing.’

“Red-flagging” is the term still used for marking library books alleged to have objectionable content — a practice occasionally requested by parents or imposed by school administrators, but frowned upon by the American Library Association and other intellectual freedom advocates (including CBLDF).

While there is no doubt that elected officials Carpentier and Stratton completely fumbled what the Washington Post simply called The Illinois Book Controversy, we will unfortunately never know for sure if Helene Rogers was actually in league with or against them. On March 25, 1954, the very day she would have met with the state library advisory committee, she suffered a stroke in her office. Rogers never recovered well enough to return to her position before she died 14 years later. What is certain, however, is that already at that time Illinois citizens themselves were willing to defend their right to read whatever they wanted — even pulp novels and popular fiction with no highbrow literary pretensions.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.