In celebration of Black History Month, CBLDF has partnered with Black Nerd Problems to spotlight Black comics creators and cartoonists who made significant contributions to free expression. Visit CBLDF.org throughout the month of February to learn more!

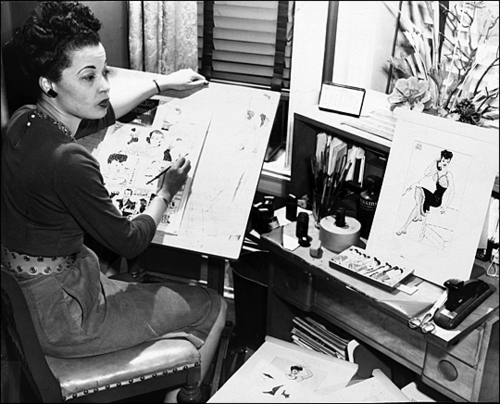

Zelda Jackson Ormes, better known as Jackie, was the first African American woman to make a living as a cartoonist. Between 1937 and 1955, her strips were syndicated extensively nationwide in the Black press, featuring Black women front and center in roles and social situations they were never accorded in the mainstream media of the day.

Ormes got her start in journalism while she was still in high school, reporting for the Pittsburgh Courier, which had a nationwide distribution. For her first assignment she covered a boxing match — with the Courier’s sports editor as a chaperone since “I was just a punk,” she said later. She relished the excitement of the news business, recalling in an interview that she “had a great career running around town looking into everything the law would allow, and writing about it.”

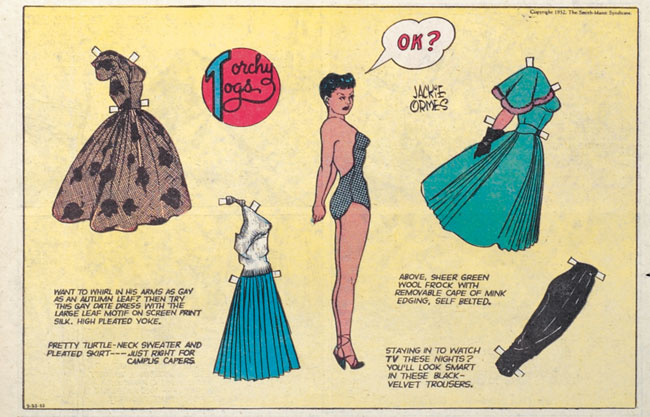

In 1937 Ormes tried her hand at cartooning with her first strip, Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem. Through the heroine Torchy, a southern transplant to New York who became a performer at the Cotton Club, Ormes was able to address not only racism and prejudice, but also women’s careers and other issues she felt strongly about. She later described herself as “antiwar [and] anti-everything-that’s-smelly.” Although Torchy Brown initially appeared only in the Pittsburgh Courier, before long the strip was syndicated in 14 more Black papers across the country.

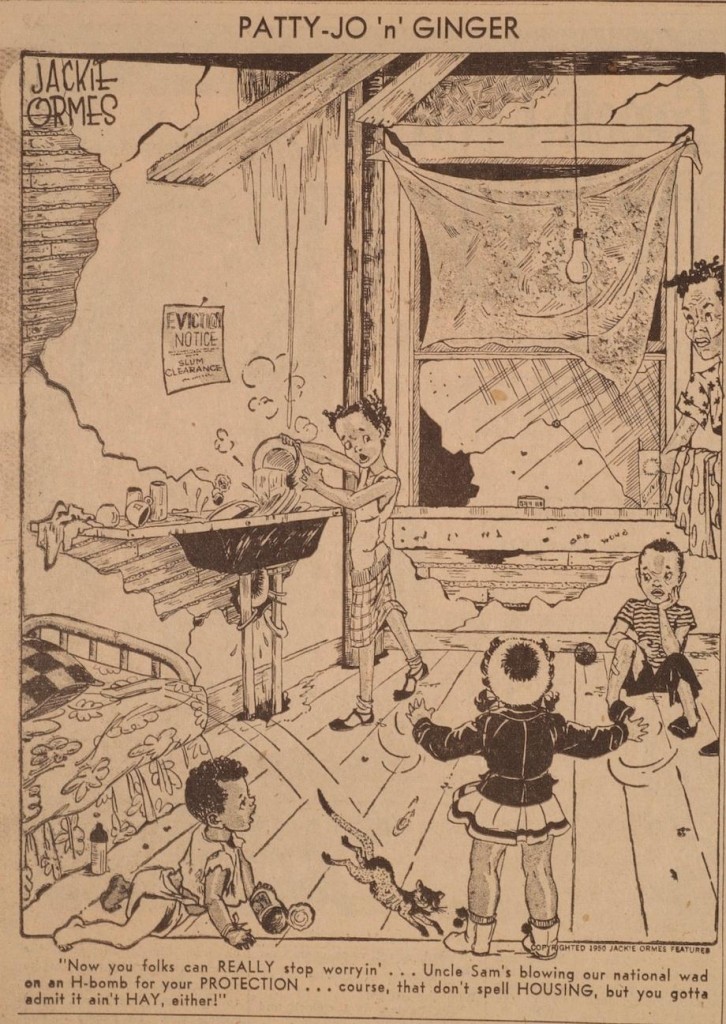

In 1940 Ormes brought the original Torchy Brown to an end and briefly moved with her husband Earl to his small hometown of Salem, Ohio, but she was unhappy there, and they soon moved again to Chicago. There, Ormes got a reporting job with the Chicago Defender, and by the mid-1940s she had conceived of another comic strip, the single-panel Candy. In 1946 she started another single-panel strip, Patty Jo ‘n’ Ginger, which featured the acerbic little girl Patty Jo and her fashion-plate older sister Ginger. Through the voice of Patty Jo, Ormes again commented on issues of the day, such as racism, sexism, the military-industrial complex, and McCarthyism. In 1948 she also licensed a Patty Jo doll, which was the first nationally distributed Black doll and remains a highly-sought-after collector’s item to this day.

In 1950 a national syndicate persuaded Ormes to bring back Torchy Brown for a new strip, Torchy in Heartbeats. Initially, however, the syndicate only wanted her to provide the art to match a male writer’s storylines. This did not work out well, as Ormes said she constantly had to remind the writer that the character she created “was no moonstruck crybaby, and that she wouldn’t perish between heartbreaks. I have never liked dreamy little women who can’t hold their own.” Eventually Ormes again gained full creative control over the strip, which ran until 1955, when papers like the Courier and the Defender cut their comics sections to give more space to news coverage of the growing Civil Rights Movement. Ormes switched to fine art painting until she also had to give that up due to rheumatoid arthritis.

By the time Ormes retired from comics, her husband was managing the historic DuSable Hotel on Chicago’s South Side, hosting a veritable who’s who of Black performers, artists, and writers visiting the city. The couple formed lifelong friendships with celebrities including Lena Horne and Sarah Vaughan. Jackie also was heavily involved in local advocacy through the Chicago Urban League and the South Side Community Art Center.

Ormes died in 1985, but in recent years her groundbreaking work has finally begun to be widely recognized. In 2008 the University of Michigan Press published a biography by Nancy Goldstein, Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist. In an interview on NPR, Goldstein stressed the importance of positive representation for Black girls and women at a crucial turning point in history:

Here’s Ginger. She’s just graduated from college. I can do that, too. Here’s Torchy. She’s challenging the racism and the status quo of the era, and I can do that, too. And so she was giving voice to what was in the hearts and minds of so many people to move forward and make progress.

But while Ormes inspired confidence in Black women generally, her own industry remains virtually off-limits to them. From 1989 to 2005 there was exactly one nationally syndicated Black woman newspaper cartoonist, Where I’m Coming From creator Barbara Brandon-Croft — who credits Ormes as an inspiration from her own youth. Brandon-Croft ended the strip over a decade ago, and any potential successors have apparently been stifled not only by the familiar combination of racism and sexism, but also by syndicates’ heavy reliance on zombie strips.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

CBLDF Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.