In celebration of Black History Month, CBLDF has partnered with Black Nerd Problems to spotlight Black comics creators and cartoonists who made significant contributions to free expression. Visit CBLDF.org throughout the month of February to learn more!

Black History Month has become a multifaceted parade of Black greatness in all of my social media feeds — first Black man to do this; first Black woman to do that. This is our community stepping in to share a history most of us didn’t learn in school, and highlighting trailblazers who brought us to the multicultural world developing around us. In that spirit, I approached learning more about Richard Eugene “Grass” Green — a pioneering fan and cartoonist whose work started in the 1960s and continued until his death in 2002.

To understand Green’s work, it helps to know about the Comics Code Authority and its impact on comic book publishing in the1950s and ’60s. As we know, the 1950s was a scary time in the US of A. The Great War was over. McCarthyism was ruining the lives of white artists and creators. Black folk were getting fed up and heading for the explosion of the Civil Rights Movement. There was a widespread concern among respectable people about the corrupting influences of comics on youth — particularly comics that featured horror, crime, and (gasp) sex. In September 1954, in an attempt to head off official censorship from the government, the leading comics publishers created their own governing body — the Comics Magazine Association of America — responsible for setting decency guidelines and handing out their seal of approval. Reputable bookstores and newspaper stands wouldn’t stock comics that didn’t bear the code seal.

Now what counted as “decent content”? You can check here for the actual list. But what really happened was that anything the censors didn’t like was out — just having a Black main character was sufficient grounds for refusing to certify a comic in 1954. As is to be expected, this silencing pushed Black comics creators and Black issues out of the mainstream publications and into the fanzines of the 1960s.

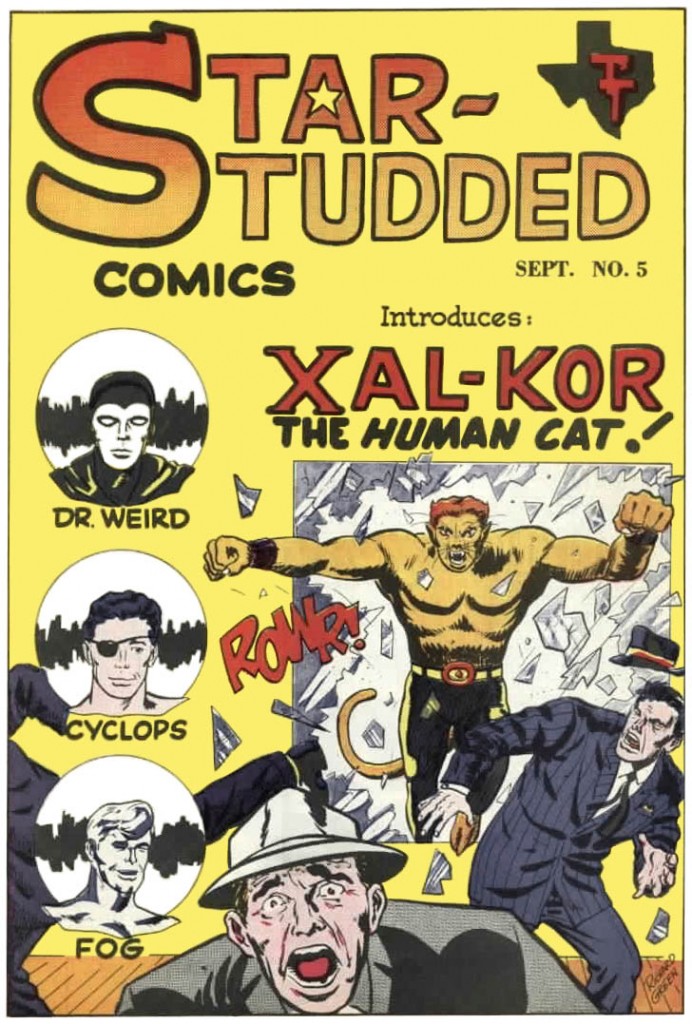

Fanzines, then as now, are content produced by and for fans of a particular pop culture topic. These are the kinds of non-traditional publications that are mail-ordered or passed person to person — censors couldn’t stop their distribution. It is into this arena that Richard “Grass” Green brought his art, debuting in fanzines like Star Studded Comics in 1964. He quickly became a fan favorite (along with, oddly enough, George R. R. Martin, who also got his writing start in Star Studded Comics in 1964).

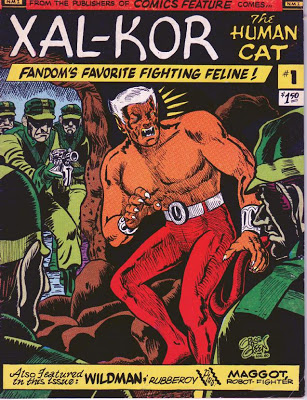

Grass Green’s most popular character was Xal-Kor the Human Cat.

Hailing from the far away planet of Felis, Xal-Kor is sent to Earth to fight the rat people by The Great White Cat. Once here, Xal-Kor starts battling Earth criminals as well. Possessing all the abilities of a cat, Xal-Kor uses his dimension belt to change from his normal form, a common house cat, to his man-cat form, or a fully human form. When human, he has an alter-ego — newspaper photographer Colin Chambers. This is all classic Golden Age comic fare.

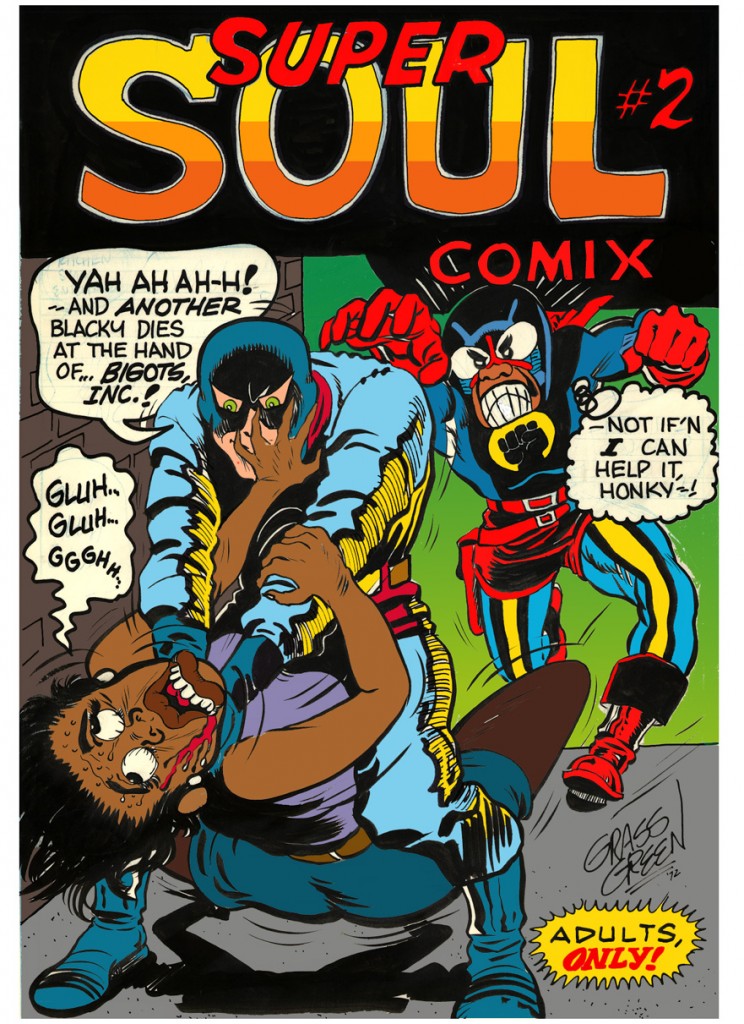

Green continued to create comics, writer, artist, and letterer, for both fanzines and professional publications throughout the late 1960s, really coming into his own with 1972 underground production of Super Soul Comix.

Underground comix (the x is intentional) was a movement of comic book creators that existed in direct defiance of the Comics Code. The comix featured crime, corruption, drug use, and sexual expressions of all types. Often pigeon-holed as the white cultural product of 1960s drug culture, underground comix provided space for Black creators to produce and distribute without requiring the rubber stamp of mainstream media. It is in the underground comix scene, distributed via non-traditional means, that the first comic with a Black superhero lead — Ebon by Larry Fuller — was born. (Note: Ebon the character debuted in 1970, after Black Panther (1966), but Black Panther didn’t headline his own books until 1973.)

Green’s Super Soul Comix featured Soul Brother American, a returning Vietnam War veteran who, after taking a beating from some police officers, takes something suspiciously similar to a Super Soldier Serum and becomes a fighter against Bigots, Inc. — a nasty corporation of racist thugs who are terrorizing his city. The comix sold 200,000 copies and is quite collectible to this day. It featured a characteristic blend of social commentary and sexually explicit content.

Green started his career as a fan artist and continued to create his art in a professional setting, a plot arc that I find personally inspiring, as any fan could. He used adult comics as a medium for commentary on American social life, a tradition that continues in modern indie, artist-owned publications. His work, along with others in the underground comix movement, introduced inclusive stories for Black people and set the stage for many of the comic book tropes we see today.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Leslie Light is a writer, mother, and editor, a damn good cook and a pathetic housekeeper. She’s a published short story author and has written her first novel — The Queen of Hunger — available through Amazon. While she loves all things nerd, she’s very tired of Wolverine.