One of the key legal cases in CBLDF’s history is that of Mike Diana, who in 1994 was actually banned from drawing for three years after a jury in Pinellas County, Florida, convicted him of obscenity for his raunchy zine Boiled Angel. In celebration of Banned Books Week, The Guardian’s David Barnett recently featured the Diana case and its repercussions — including Neil Gaiman’s 12-year tenure on CBLDF’s board of directors and his generous ongoing support of our education programs via the Gaiman Foundation.

One of the key legal cases in CBLDF’s history is that of Mike Diana, who in 1994 was actually banned from drawing for three years after a jury in Pinellas County, Florida, convicted him of obscenity for his raunchy zine Boiled Angel. In celebration of Banned Books Week, The Guardian’s David Barnett recently featured the Diana case and its repercussions — including Neil Gaiman’s 12-year tenure on CBLDF’s board of directors and his generous ongoing support of our education programs via the Gaiman Foundation.

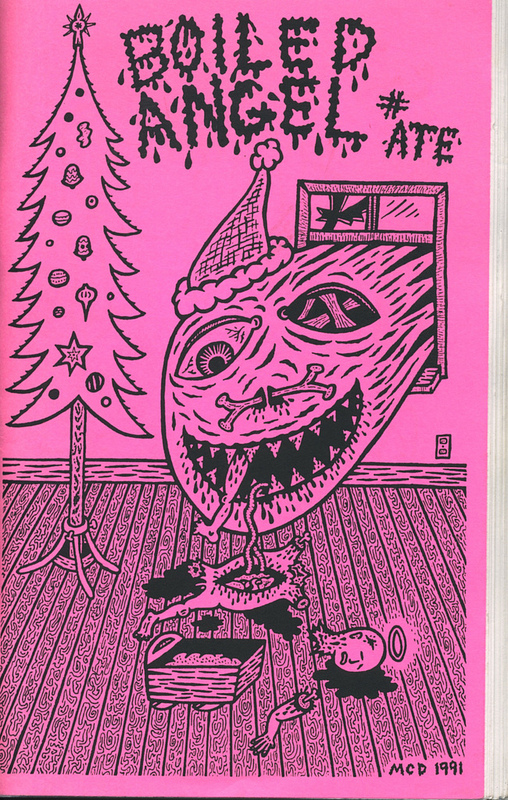

There is no question that Mike Diana’s work, influenced by surrealist art as well as underground and horror comics, is well out of the mainstream — which is precisely the sort of content that CBLDF was founded to defend in 1986, after the police raid of Chicago-area Friendly Frank’s comic shop and the arrest of store manager Michael Correa. Like the underground comix by Denis Kitchen, Robert Crumb, and others seized in that raid, Diana’s Boiled Angel featured nudity and sexuality, but also extreme violence, including mutilation, rape, and child molestation, as well as taboo subjects such as necrophilia and cannibalism.

Diana came to the FBI’s attention in 1991 after some issues of Boiled Angel were found in the possession of Danny Rolling, then under investigation for the serial murders of five Gainesville students. Rolling acted alone and would later plead guilty in 1994 before being executed in 2006, but investigators apparently thought Diana could have been an accomplice based on no evidence apart from Boiled Angel. He was cleared of involvement in the murders after providing a blood sample, but the FBI turned his work over to local police, who then charged him with obscenity.

This is where CBLDF came in, financing Diana’s defense by local attorney Luke Lirot. Despite Lirot’s valiant efforts and the fact that Boiled Angel did not meet the definition of obscenity as laid out in the three-pronged Miller Test, Diana was convicted and received a fine of $3,000, as well as a sentence of three years’ probation, which included stipulations that he stay away from minors and refrain from drawing. He found this last condition to be untenable, later admitting that he hid works-in-progress in the trunk of his car in case of surprise police checks on his home.

Although this outcome certainly was not favorable for Diana, the blatantly unconstitutional conviction and sentence galvanized free speech advocates in and out of the comics industry, much the same way they had united around Correa and Friendly Frank’s eight years earlier. Neil Gaiman cites the Diana case as his direct inspiration for joining CBLDF’s board of directors in 1992, based on his strong conviction that “you can always defend someone who is essentially just making marks on paper,” even if their work may seem repulsive to the average viewer.

When Gaiman retired from the board over a decade later, his foundation donated $60,000 to kickstart our education programs, which he hoped could “provide information and advice to anyone feeling threatened by censorship, to any shop told it can’t sell comics, to the librarians whose jobs are on the line because someone doesn’t like to see an Alan Moore graphic novel contaminating the shelves.” Today, the Gaiman Foundation backs several CBLDF education initiatives, including our quarterly news magazine Defender, our podcast, our Banned Books Week handbooks, and much more. By promoting awareness of the comics medium and related First Amendment issues, CBLDF hopes to prevent any future repeats of the Mike Diana scenario — although of course our legal resources are at the ready if it does happen!

Check out Barnett’s article on CBLDF, Gaiman, and the Mike Diana case here at The Guardian.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.