Welcome to Using Graphic Novels in Education, an ongoing feature from CBLDF that is designed to allay confusion around the content of graphic novels and to help parents and teachers raise readers. In this column, we examine graphic novels, including those that have been targeted by censors, and provide teaching and discussion suggestions for the use of such books in classrooms.

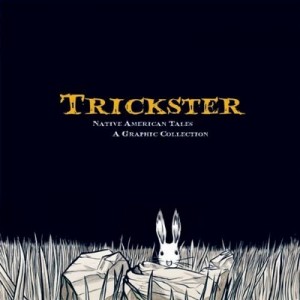

This post takes a closer look at the Trickster: Native American Tales: A Graphic Collection, compiled and edited by Matt Dembicki.

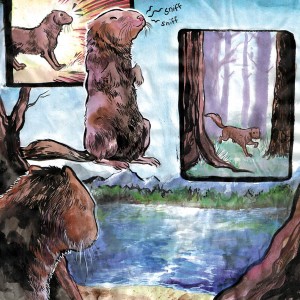

Trickster collects 21 Native American tales from across the continent. In Native American traditions, the Trickster takes many forms and the diversity of the Trickster’s form and talents are clearly reflected in this anthology. Whether a coyote, rabbit, raccoon, raven, beaver, fox, or man, Trickster is always a crafty creature who disrupts, humiliates, or betters himself or those around him.

In this anthology, Dembicki has paired Native storytellers with a writer or artist, and he illustrated one of the stories as well. The stories come from all over the United States. The range of locations adds to the range and depth of the selected stories. Trickster is the recipient of the 2010 Maverick Award, the 2011 Aesop Prize for Children’s folklore, and a 2011 Eisner Award Nominee.

Trickster includes the following stories:

- “Coyote and the Pebbles” by Dayton Edmonds and Micah Farritor

- “Raven the Trickster” by John Active and Jason Copland

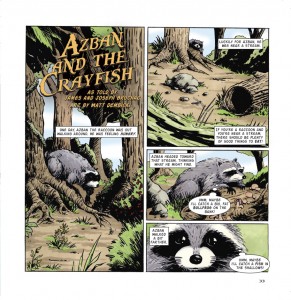

- “Azban and the Crayfish” by James Bruchac, Joseph Bruchac, and Matt Dembicki

- “Trickster and the Great Chief” by David Smith and Jerry Carr

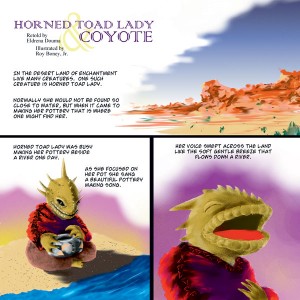

- “Horned Toad Lady and Coyote” by Eldrena Douma and Roy Boney Jr.

- “Rabbit and the Tug-of-War” by Michael Thompson and Jacob Arrenfeltz

- “Moshup’s Bridge” by Jonathan Perry, Chris Piers, and Scott White

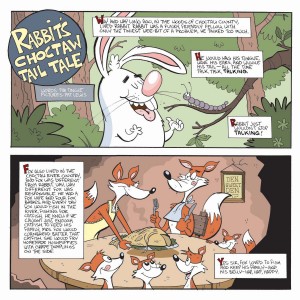

- “Rabbit’s Choctaw Tail Tale” by Tim Tingle and Pat Lewis

- “The Wolf and the Mink” by Elaine Grinnell and Michelle Silva

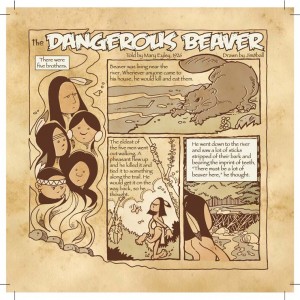

- “The Dangerous Beaver” by Mary Eyley and Jim8ball

- “Giddy up, Wolfie” by Greg Rodgers and Mike Short

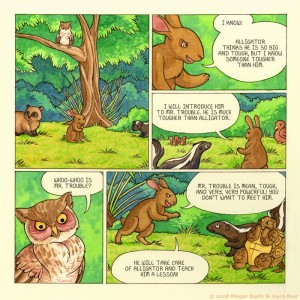

- “How the Alligator Got His Brown, Scaly Skin” by Joyce Bear and Megan Baehr

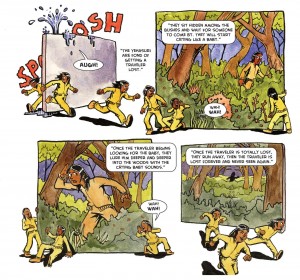

- “The Yehasuri, the Little Wild Indians” by Beckee Garris and Andrew Cohen

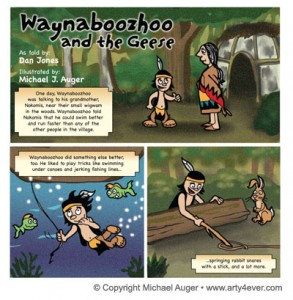

- “Waynaboozhoo and the Geese” by Dan Jones and Michael J. Auger

- “When Coyote Decided to Get Married” by Eirik Thorsgard and Rand Arrington

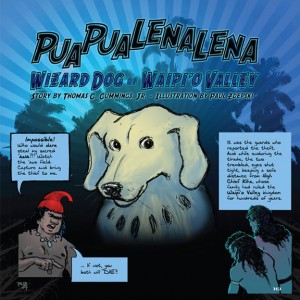

- “Puapualenalena, Wizard Dog of Waipi’o Valley” by Thomas C. Cummings Jr. and Paul Zdepski

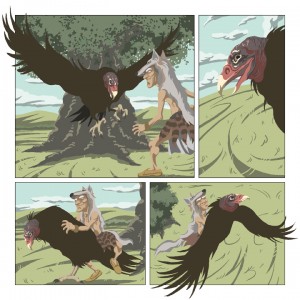

- “Ishjinki and Buzzard” by Jimm Goodtracks and Dimi Macheras

- “The Bear Who Stole the Chinook” by Jack Gladstone and Evan Keeling

- “How Wildcat Caught a Turkey” by Joseph Stands With Many and Jon Sperry

- “Espun and Grandfather” by John Bear Mitchell and Andy Bennett

- “Mai and the Cliff-Dwelling Birds” by Sunny Dooley and J. Chris Campbell

OVERVIEW

What is so nice about Trickster is that it is an eclectic collection of stories and artistic styles. As the stories come from across North America, the stories and the depictions of Trickster reflect multidimensional characters we learn to love, fear, and/or respect. In some cases the Trickster is cruel albeit creative and smart. In other cases the Trickster is wise or powerful, small or large. Furthermore, while almost all depictions of Trickster are animals, because the stories come from different places, the rabbits or foxes or ravens or wolves vary in character and craftiness. Through most of these stories the Trickster is wonderfully developed, making this a fun read for all ages. The art is also wonderfully engaging and artistic styles and designs range widely. Throughout the book, the artistic design and use of colors reflect the locale of the story.

SERIES SUMMARY

Below is a brief description of each of the stories:

“Coyote and the Pebbles” by Dayton Edmonds and Micah Farritor is about how the stars were placed in the sky: They were pebbles thrown to the heavens by coyote, who, when asked to help the others create more light in the sky, came too late. Coyote did not follow instructions like the others and is banned from their celebrations. As a result he now stands alone at night howling at the sky. The art uses greys and sepia tones, and the animals morph from animal to human form and back. The art and design are rich in detail, and the dark, somber colors reflect the tone and theme of the story.

“Raven the Trickster” by John Active and Jason Copland is about how the raven tricked a sea anemone and ended up with a much larger meal. Copland uses a limited palette of light blues for water, greens, and browns. His color decisions add to the feel of life in the bogs, where the story unfolds.

“Azban and the Crayfish” by James Bruchac, Joseph Bruchac, and Matt Dembicki is a story about how Azban, a raccoon Trickster, desperately hungry, came upon a crayfish. But instead of eating the crayfish, Azban fooled him into bringing his entire community. Dembicki uses greens, blacks and browns to depict stream and forest life and the panel shapes, design, and organization are wonderfully engaging.

“Trickster and the Great Chief” by David Smith and Jerry Carr is one of the simpler stories both in terms of content and art and design. In this story, Trickster, in human form, is out for a walk. He comes upon a tribe mourning the loss of their leader. Trickster decides to rob the dead leader of his fine furs and bow but gets caught by the dead chief’s spirit. Trickster apologizes and makes everything right again, teaching readers to respect the dead.

“Horned Toad Lady and Coyote” by Eldrena Douma and Roy Boney Jr. is about Coyote, who stumbles across Horned Toad Lady as she makes pots by a river in the desert. She’s singing a beautiful song, and he wants to learn it. She tells him it’s a pottery song that horned toads sing, not coyotes. But he pushes her, and in fear of being eaten, she sings it. He learns it, forgets it, and returns. When Horned Toad Lady refuses to teach it again, he eats her, instantly regretting it because he realized too late he’d never hear it again. While the panel arrangement here is simple, the art is very different from the other stories as figures are drawn to look like clay figures in front of simple backgrounds.

“Rabbit and the Tug-of-War” by Michael Thompson and Jacob Arrenfeltz is about how Rabbit decides to have some fun with two buffalo. He tricks each into a tug-of-war. While each buffalo thinks he’s in for an easy win against a rabbit, they are actually having a tug-of-war with each other. The art is deceptively complex, the panel arrangement is engaging, and it is all done in varying shades of brown and black.

“Moshup’s Bridge” by Jonathan Perry, Chris Piers, and Scott White takes place along the coast of “Noepe our name for the island of Martha’s Vineyard.” It is about Moshup, a giant who decides to build a bridge to the chain of islands nearby. The jealous and prying Cheepee hears this and tricks Moshup, who never finishes the bridge as a result.

“Rabbit’s Choctaw Tail Tale” by Tim Tingle and Pat Lewis is about how the rabbit got his tail (spoiler alert: he was outfoxed by fox). This story is drawn in a wonderfully engaging and inviting cartoon style and is a lot of fun to read as the humor oozes from text and images.

“The Wolf and the Mink” by Elaine Grinnell and Michelle Silva is about a mink who doesn’t want to share his hard-caught fish. Mink is soon outwitted by Wolf, who takes all Mink’s food while he’s sleeping. Upon waking, Mink doesn’t remember eating his food but since it’s not there, he decides “Hey I must have eating those fish. If I’ve eaten two fish, then I must be full!” The story is drawn in rich, dark watercolors, using browns, greens, and purples that add to the feeling of the forest in which it takes place.

“The Dangerous Beaver” by Mary Eyley and Jimbball is about an evil beaver who tricks, kills, and eats four of five brothers. The fifth brother however, while searching for his brothers, stumbles upon an injured meadow lark. He fixes its leg, and in return the lark warns him of the evil beaver. The youngest brother strikes Beaver (as instructed by Lark). Beaver becomes the mild animal we are all familiar with, and the brothers’ bones came to life. This story is told in sepia colors with wonderful panel and page design. While not as colorful as the other stories, the color choice adds an earthy feeling to the story.

“Giddy Up, Wolfie” by Greg Rodgers and Mike Short is a story about how Rabbit, who loves a wolf, tricks her into loving him. It is smart, tricky, and drawn in an array of vibrant colors.

“How the Alligator Got His Brown, Scaly Skin” by Joyce Bear and Megan Baehr is about how Alligator got his brown scaly skin by being mean, and how Rabbit taught Alligator a lesson: If he doesn’t behave “Mr. Trouble” will teach him another lesson.

“The Yehasuri, the Little Wild Indians” by Beckee Garris and Andrew Cohen is about The Yehasuri – wild little Indians who inhabit the native spirit world of the Catawba. Native American children are told stories of the Yehasuri and how they particularly enjoy taunting children who misbehave. In this story, Cohen plays with borders and gutters and has the Yehasuri running in, through, and around the panels, emphasizing their mischievous nature.

“Waynaboozhoo and the Geese” by Dan Jones and Michael J. Auger is about Wyanaboozhoo who claims to be the best swimmer and fastest runner in his village and who likes to play tricks like swimming under canoes and jerking fishing lines. One day, he plays a trick on geese. What’s interesting about this story is that there is no clear end or repercussions, and it’s up to the reader to decide the characters’ fates.

“When Coyote Decided to Get Married” by Eirik Thorsgard and Rand Arrington is about Coyote, who seeks a wife. He wants the purest, most beautiful woman he can find. Coyote, “ being a hero and chiefly individual with strong medicine, would be a great addition to any family” so each father vied for the prize. One day Coyote finds the woman he wants, and while she secretly loves another, allows her family to offer her to Coyote. Coyote, however, sees in her eyes that her love for him is not pure and punishes them all by turning them into stone. Drawn in earth tones, many of the panels are borderless, adding a nice depth to the storytelling.

“Puapualenalena, Wizard Dog of Waipi’o Valley” by Thomas C. Cummings Jr. and Paul Zdepski is about a Wizard Dog, who through cunning and bravery restores the sacred conch shell to its tribe by outwitting the spirits and saving his master. Zdepski brilliantly illustrates the story. It is more an illustrated story than one told with sequential panels but this adds to the magic and trickery.

From “Puapualenalena Wizard Dog of Waipi’o Valley,” retold by Thomas C. Cummings, Jr. Art by Paul Zdepski.

“Ishjinki and Buzzard” by Jimm Goodtracks and Dimi Macheras is about Ishjinki, who dresses in a robe of a raccoon skins and asks Buzzard to pity him because he wants “to walk just as you walk.” Buzzard warns him that he won’t be able to get used to it but eventually Buzzard gives in to Ishjinki, and has him ride on his back as he flies. Ishjinki eventually falls off and seeks revenge over Buzzard. This is why today Buzzard has a bald head “and he stinks very much.”

“The Bear Who Stole the Chinook” by Jack Gladstone and Evan Keeling is actually an illustrated song. It’s about a tribe that discovers that Bear has stolen the Chinook in the dead of winter. An orphan boy called the animals to his home as the Elders of the council met and prayed. Each animal tried unsuccessfully to take the Chinook from Bear. Then, the boy made medicine smoke appear, and as Bear finally slept, Coyote crept in, released the wind from a bag and “the warm wind never was again his friend.” That is why bears hibernate in winter. As Gladstone breaks the song into individual panels, Keeling’s art — in particular the wind — is wonderfully moving.

“How Wildcat Caught a Turkey” by Joseph Stands With Many and Jon Sperry is about how Rabbit saves himself from the Wildcat’s jaws by helping him find more substantial meal — turkeys. Rabbit tells Wildcat to play dead while he promises to lure the turkeys to him… “And that’s how wildcat caught himself a turkey!”

“Espun and Grandfather” by John Bear Mitchell and Andy Bennett is about Espun “a curious person” in the form of a long legged raccoon. This is essentially a story of how Espun, who traveled the world and looked for something new, finds Grandfather Rock, who never travels. Through mischief and mishap, the story is about how Raccoon ends up with the short legs he has today.

“Mai and the Cliff-Dwelling Birds” by Sunny Dooley and J. Chris Campbellis drawn in vibrant pastel colors. It is about Mai, a coyote that trotted everywhere, never satisfied with what he saw, heard, smelled, tasted, or touched. One day, he saw a flock if birds and he asked one to teach him to fly. The bird reluctantly agreed (after much prodding from Mai) on the condition that he’d give Mai three lessons. Mai has some success, and finds two blue jays who were tossing their eyes into the air while flying under them to catch them. Mai wanted to try but missed catching his eyes. The blue jays couldn’t understand why he was upset because “He never used his eyes to see anything anyway…”

In short Trickster is an anthology of stories depicting how various characters — some well-intentioned, some ill-intentioned, and some simply mischievous — creatively devise plans to get what they need, whether it’s entertainment, revenge, particular skills, or food. It also is a collection of how very different and diverse characters interact and the diversity of Native storytelling.

TEACHING/DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS:

Plot, Themes, and Values Related

- Chart and discuss the themes and the morals of each story. You may want to break the class into groups, each given a story to analyze, discuss, and present.

- Divide the stories according to their location (i.e., desert states, forest, mountains, island, water, Eastern states, etc.). Evaluate how location influences the story’s plot and values.

- Have students discuss how each story makes them feel. Discuss the power of sad versus funny stories and the values they relate.

Critical Reading and Making Inferences

- In each of the stories, the Trickster is a human, raccoon, alligator, coyote, wolf, dog, raven bear, rabbit, or beaver. What traits are found in all of the Tricksters and what traits pertain to the type of creature they are?

- In some of the stories, the Trickster is called, “Rabbit” or “Coyote” or whatever animal form the Trickster takes. In others, the character has a specific name (such as “Azban, the Man-Eater” or “Paupualenalena, the Wizard Dog of Waipi’O Valley). Discuss how the name may or may not influence the story.

- There are four stories about Rabbit the Trickster (“Rabbit and the Tug of War;” “Rabbit’s Choctaw Tail Tale;” “Giddy Up, Wolfie;” and “How Wildcat Caught a Turkey”). Have students compare and contrast Rabbit’s character in each story. What appear to be universal traits and what traits seems to be unique to each particular story? Compare and contrast the stories, discussing traits and themes that overlap versus traits and themes unique to that story.

- There are several stories about Coyote the Trickster (“Coyote and the Pebbles;” “Horned Toad Lady and Coyote;” and “When Coyote Got Married”). Have students compare and contrast Coyote’s character in each story and the way he is portrayed (his color, his size, etc.). What appear to be universal traits and what traits seems to be unique to each particular story? Compare and contrast the stories, discussing traits and themes that overlap versus traits and themes unique to that story.

- There are two stories about Raccoon the Trickster (“Azban and the Crayfish” and “Espun and Grandfather”). Have students compare and contrast Raccoon’s character in each story and the way he is portrayed (his color, his size, etc.). What appear to be universal traits and what traits seems to be unique to each particular story? Compare and contrast the stories, discussing traits and themes that overlap versus traits and themes unique to that story.

Language, Literature, and Language Usage

- As each story is told by a relayed a different author, evaluate and discuss how the storytelling changes from story to story. Evaluate, for example, the use of simile, metaphor, and hyperbole in each of the stories. How do literary devices help the telling of the story?

- Discuss how the stories’ titles promote the story’s theme or its characters. Discuss which titles appear to be more or less successful in setting the story’s tone or theme.

- In Giddy Up, Wolfie, when Chockfi invites Rabbit in to her cave for dinner (p. 115) she says, “Come on in… scrumptious.” Discuss how Rabbit and Chockfi interpret “scrumptious” differently.

Modes of Storytelling and Visual Literacy

In graphic novels, images are used to relay messages with and without accompanying text, adding additional dimension to the story. Trickster, being an anthology, offers a wonderful opportunity to see how color, formatting and design play a unique role in storytelling.For example:

- The stories come from different regions in the United States. How does the color reflect the locale of each story?

- How does the choice of color in each story reflect its mood and its theme?

- Compare and contrast the different styles used by each of the artists. For example some or realistically drawn, some are cartoons, etc. How does the format reflect the tone, theme, and/or location of the story? How does it reflect the characters’ dispositions?

- Some stories use simple panel and page design and others incorporate more sophisticated choices in panel arrangement and page design. Discuss how these differences influence and affect the storytelling.

Suggested Prose Novel and Poetry Pairings

For greater discussion on literary style and/or content here are some prose novels about growing up, about being a pre-teen/teen, and about challenges of middle school and high school that you may want to read and pair with Trickster:

- XOC by Matt Dembicki: the story of a great white shark that brilliantly shows the shark as both predator and prey and relays the perils posed by man not only in hunting the great white but in polluting the waters they swim in.

- Trick of the Tale: A Collection of Trickster Tales by John and Caitlin Matthews: a multicultural array of Trickster stories from around the world.

- The Coyote Road: Trickster Tales edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling: a collection of Trickster stories from around the world, written by twenty-six authors including Holly Black, Charles de Lint, and Jane Yolen.

- Anansi the Spider: A Tale from the Ashanti by Gerlad McDermott: a retelling of the story from the Ashanti of West Africa. It is a picture book and the art clearly reflects the culture from which the story came.

- Coyote: A Trickster Tale from the American Southwest by Gerald McDermott: a vividly illustrated story of how Coyote desperately tries to lean to sing, dance, and fly like the crows.

- Raven: A Trickster Tale from the Pacific Northwest by Gerald McDermott: a beautifully illustrated story of how Raven wants to give people the gift of light but needs to find where Sky Chief keeps it.

- American Indian Trickster Tales (Myths and Legends) by Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz: a collection of illustrated short stories from over sixty tribes.

- Coyote Tales of the Northwest by Thomas George: a collection of Coyote tales from the Pacific Northwest.

- Raven and the First People: Legends of the Northwest Coast by Thomas George: a collection of Raven tales from the West Coast.

Common Core State Standards (CCSS):

As this is an anthology, its 21 stories all have very different voices — different art and design and different stories. As a result it reaches ages 8 and older and can be incorporated into language arts and content-area classes for a variety of grades. I therefore will be using the Common Core Anchor Standards for College and Career Readiness for Reading, Writing, and Speaking and Listening. Reading Trickster and incorporating the teaching suggestions above promotes critical thinking and its graphic novel format provides verbal and visual story telling across subject areas while addressing multi-modal teaching. Here’s a more detailed look:

- Knowledge of Language: Apply knowledge of language to understand how language functions in different contexts, to make effective choices for meaning or style, to comprehend more fully when reading or listening.

- Vocabulary Acquisition and Use: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases by using context clues, analyzing meaningful word parts, and consulting general and specialized reference materials; demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meaning; acquire and use accurately a range of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases sufficient for reading, writing, speaking and listening at the college and career readiness level.

- Key ideas and details: Reading closely to determine what the texts says explicitly and making logical inferences from it; citing specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text; determining central ideas or themes and analyzing their development; summarizing the key supporting details and ideas; analyzing how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of the text.

- Craft and structure: Interpreting words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings and analyzing how specific word choices shape meaning or tone; analyzing the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs and larger portions of the text relate to each other and the whole; Assessing how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

- Integration of knowledge and ideas: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually…as well as in words; delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence; analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take

- Range of reading and level of text complexity: Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently

- Comprehension and collaboration: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively; integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively and orally; evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

- Native American Tricksters of Myth and Legend, http://www.native-languages.org/trickster.htm — contains a long list of Tricksters from various tribes. It has their original names and pronunciations, it has tribal origins to famous tales along with links for each tale.

- Interview with Matt Dembicki at NPR, http://www.npr.org/2010/06/06/127483926/native-american-folk-tales-take-a-graphic-turn — with some wonderful background into the making of the book and its collection of stories. Joseph Stands With Many reads his story from the anthology, “How Wild Cat Caught a Turkey.”

- Dembicki also speaks with the Washington City Paper, which ran interviews with many of the book’s creators, including Paul Zdepski, Michael Auger, Chris Piers, Andrew Cohen, and Jacob Warrenfeltz.

- Anansi stories at http://anansistories.com/ — a wonderful collection of Anansi the trickster spider in African and Caribbean folklore. This site has a variety of Anansi stories and discusses how Anansi came to America.

- Myths and Legends, http://myths.e2bn.org/mythsandlegends/origins11717-anansi-brings-stories-to-the-world.html — discusses the Anansi story and has links for teacher guides to help students create their own stories.

- Trickster tales from around the world, http://kidworldcitizen.org/2014/01/17/trickster-tales-around-world/— Discusses what Trickster tales are, and has links to various Trickster tales from around the world.

Meryl Jaffe, PhD teaches visual literacy and critical reading at Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth OnLine Division and is the author of Raising a Reader! and Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning. She used to encourage the “classics” to the exclusion comics, but with her kids’ intervention, Meryl has become an avid graphic novel fan. She now incorporates them in her work, believing that the educational process must reflect the imagination and intellectual flexibility it hopes to nurture. In this monthly feature, Meryl and CBLDF hope to empower educators and encourage an ongoing dialogue promoting kids’ right to read while utilizing the rich educational opportunities graphic novels have to offer. Please continue the dialogue with your own comments, teaching, reading, or discussion ideas at meryl.jaffe@cbldf.org and please visit Dr. Jaffe at http://www.departingthe text.blogspot.com.