After coming across one instance of pixelated genitals in the YA graphic novel Mangaman, a mother in Issaquah, Washington, plans to formally request that the book be removed and/or restricted in the library at her 14-year-old son’s high school. In observance of their challenge policy, Issaquah School District administrators have pointed Shirley Lopez towards the Request for Re-evaluation of Materials form. Lopez has in the meantime aired her grievance with a local news station, attacking the school for making the book available.

After coming across one instance of pixelated genitals in the YA graphic novel Mangaman, a mother in Issaquah, Washington, plans to formally request that the book be removed and/or restricted in the library at her 14-year-old son’s high school. In observance of their challenge policy, Issaquah School District administrators have pointed Shirley Lopez towards the Request for Re-evaluation of Materials form. Lopez has in the meantime aired her grievance with a local news station, attacking the school for making the book available.

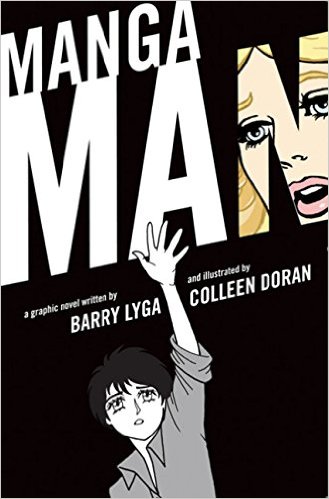

Mangaman was written by Barry Lyga and illustrated by Colleen Doran. It tells the story of Ryoko, a manga character who falls through a dimensional rift into a real-world American high school. The book received starred reviews from Kirkus (“an inventive offering, sure to please fans of both American and Japanese comics”) and School Library Journal (“a story full of clever humor and human emotions”), as well as praise from Bone creator Jeff Smith, who called it “an eye-popping fun-ride through the comics traditions of East and West.” All available reviews judge it to be appropriate for high-school-aged readers, while some even go a bit younger (12-13) in their recommendations.

In the clever metanarrative of Mangaman, Ryoko has trouble fitting in at his new school because he involuntarily brought with him various manga conventions: heart eyes when he develops a crush on the beautiful Marissa Montaigne, speed lines when he moves fast, and perhaps most embarrassing of all, pixelated genitals. On the page that Lopez flagged as objectionable, the nude Ryoko sheepishly cites Article 175 of Japan’s Criminal Code to assure Marissa that “it’s there, you just can’t see it.” In the next few panels both Ryoko and Marissa admit with relief that they are not yet ready to have sex anyway.

Lopez told local news station KIRO that she considers Mangaman to be “erotica,” but to the contrary, it actually speaks to teen manga fans with sly visual tropes they already understand about an awkward situation many of them probably recognize.

Nevertheless, Lopez insists she does not “want my kid to be feeding his mind with that.” She has already spoken to Issaquah High School’s librarian and principal, both of whom judged the book appropriate to remain on library shelves. They did offer to bar Lopez’s son from checking it out while keeping it available to other students, but she was apparently unsatisfied with that solution. A district spokeswoman told KIRO that the next step would be for Lopez to fill out and submit a challenge form, and she said she intends to do that. The form does ask if the complainant has read the material in its entirety, but does not require that they do so before submitting.

If and when Lopez does file a formal challenge to Mangaman, the book will be assessed by the standing Instructional Materials Committee, consisting of 17 members including eight teachers and three librarians from all school levels, five community members, and a non-voting chairperson. They will issue a recommendation within two weeks, and if Lopez is not satisfied with the decision she can appeal it to the school board which would have the final say. In the meantime, district policy says the book is to remain available in the library. We will be watching this case closely, so stay tuned for updates!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.