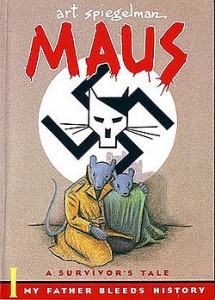

We may be biased (we’re biased), but it is difficult to see how the increased use of comics in higher education could be a bad thing. Starting with Art Spiegelman’s Maus over thirty years ago, educators at all levels have discovered the unique benefits of graphic literature in the classroom. Today entire courses built around comics can be found at every type of post-secondary institution from community colleges to large universities.

We may be biased (we’re biased), but it is difficult to see how the increased use of comics in higher education could be a bad thing. Starting with Art Spiegelman’s Maus over thirty years ago, educators at all levels have discovered the unique benefits of graphic literature in the classroom. Today entire courses built around comics can be found at every type of post-secondary institution from community colleges to large universities.

Nevertheless, the advancement of comics in academia is also inspiring some hand-wringing backlash from certain pundits, as a recent post from The Beat’s Heidi MacDonald shows. George Leef, director of research for a North Carolina-based think tank called the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, published a brief article this week on National Review’s The Corner which summarized a longer report by Shannon Watkins of the Martin Center. Watkins’ piece is titled “Graphic Novels Are Trending in English Departments, and That’s a Problem.”

Watkins cites some of the most commonly assigned–and challenged–graphic novels, including Maus and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. While she purports to believe that “graphic novels do have artistic merit, and are of aesthetic interest,” she also makes the unsupported claim that “they don’t possess the same merit as traditional literature.” Her main concern, however–the one she mentions first–seems to be that “the majority of graphic novels tend to advance political agendas.” As evidence of this, Watkins cites Fun Home and Kelly Sue DeConnick’s Bitch Planet.

Fun Home in particular has been a locus of controversy at the post-secondary level. In 2014 some South Carolina legislators attempted to enact punitive budget cuts against the College of Charleston for selecting Bechdel’s memoir as an optional summer reading book. Ultimately the funds were restored to the College’s budget, but earmarked only for “teach[ing] the U.S. Constitution, Declaration of Independence and Federalist papers”–topics that are already covered in history courses.

The following year, Duke University in North Carolina selected Fun Home as an optional summer reading book for the incoming freshman class. Although many students appreciated the selection and the conversation it inspired, others objected and at least one proclaimed that he would not read the book (again, optional) because it was “pornographic.” That same year in California, Fun Home was one of four graphic novels that a community college student said should be “eradicated from the system,” while back in North Carolina a UNC freshman wrote a column critical of a course he was not taking called ‘Literature of 9/11,’ which included Spiegelman’s book In the Shadow of No Towers.

Despite Watkins’ repeated contention that graphic novels are not as “intellectually demanding” as prose texts, the objection in each of these cases was not that the books were too simplistic or unserious, but rather that they treated topics the readers (or non-readers as the case may be) simply didn’t expect to encounter in comics. The California student made this quite clear when she confessed that in signing up for a class on graphic novels, she “expected Batman and Robin, not pornography.”

This ignorance of the format only proves all the more that post-secondary students should be exposed to the unique storytelling modes that graphic literature makes possible. While Watkins alleges that comics are “in some cases supplanting more standard text-based curricula,” no one is actually proposing that they should be the only literature studied at any level. Whether critics like it or not, however, graphic novels are finally being accorded their place in the academic canon. We happen to believe that students can only benefit from experiencing new ways to consume and critique texts in all formats!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.