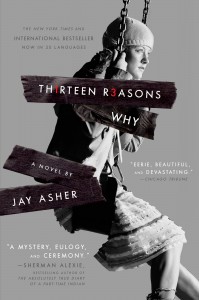

Jay Asher’s young adult novel Thirteen Reasons Why, first published 10 years ago, has recently returned to the national spotlight due to this year’s Netflix series based on it–which is both a hit with teens and a source of anxiety for parents and school administrators, who worry that it may glamorize or otherwise encourage suicide. As a recent blog post from the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom shows, however, Asher has heard these arguments before–but he’s also heard from teens whose lives were saved because they recognized their own experience in the book and found the strength to seek help.

Jay Asher’s young adult novel Thirteen Reasons Why, first published 10 years ago, has recently returned to the national spotlight due to this year’s Netflix series based on it–which is both a hit with teens and a source of anxiety for parents and school administrators, who worry that it may glamorize or otherwise encourage suicide. As a recent blog post from the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom shows, however, Asher has heard these arguments before–but he’s also heard from teens whose lives were saved because they recognized their own experience in the book and found the strength to seek help.

It may seem strange to classify Thirteen Reasons Why as an example of what fellow YA author Laurie Halse Anderson has dubbed “resilience literature”; main character Hannah Baker does kill herself, after all. But the vital role of books that deal with difficult experiences faced by real teens every day, like Thirteen Reasons Why, Anderson’s Speak, Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, and Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower, is to inspire resilience in the readers who need it, even if the fictional characters don’t always come through unscathed.

Sadly, each of the books listed above is also frequently challenged by adults who hone in on single words or out-of-context passages without considering the positive impact of the entire work. For Asher, this point was driven home in 2013 when his book made the previous year’s Top Ten List of Frequently Banned and Challenged Books:

The very day I found out ‘Thirteen Reasons Why’ was the third most challenged book, I received an e-mail from from a reader claiming my book kept her from committing suicide. I dare any censor to tell that girl it was inappropriate for her to read my book.

When Asher hears from a librarian or teacher fighting a challenge to the book, he forwards them emails like that one to show that preserving access to it could actually be a question of life or death. He adds that his conversations with readers, both online and face-to-face, have only strengthened his belief that they deserve and respond to honesty when reading about difficult topics:

Having spoken to thousands of teens since my book came out, I even more firmly believe that books dealing with these issues need to be written as emotionally honest as possible. Not only is it appropriate, it’s responsible. If people are dealing with it, we need to talk about it. Otherwise, we contribute to the main reason people don’t reach out for help. I consistently hear readers say my book was the first time they felt understood, which is sad. I’m sure many people around them would understand. If my book proves that there are people who get what they’re going through, I’m honored.

It is quite understandable that some adults react to books like Thirteen Reasons Why by trying to shield teens from the terrifying specter of suicide. Each parent, of course, is free to decide whether their own child is ready to read the book–but as Asher argues convincingly, they should not presume to make that judgment for all teens. Read the full post from OIF here.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.