There is no doubt that in the proper pedagogical context, reading level scores like Lexile and Accelerated Reader can serve as useful tools for measuring young readers’ progress compared to their peer group. All too often, though, students are restricted from reading the books they would actually enjoy–the ones that would make leisure reading a positive experience and hopefully a lifelong habit–simply because they’re expected to meet one of these third-party benchmarks.

There is no doubt that in the proper pedagogical context, reading level scores like Lexile and Accelerated Reader can serve as useful tools for measuring young readers’ progress compared to their peer group. All too often, though, students are restricted from reading the books they would actually enjoy–the ones that would make leisure reading a positive experience and hopefully a lifelong habit–simply because they’re expected to meet one of these third-party benchmarks.

This week in a post on the blog of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, longtime school librarian and recent Ph.D. graduate April Dawkins delved into the issues that arise when students are directed to only choose books that fall within a certain coldly calculated range. She didn’t need to look far for a prime example: when her niece was a high-achieving reader in the 6th grade, she recalls, the only books in the school library that matched her Lexile level were the novels of James Fenimore Cooper. “Do you want to turn off a student from reading?” asks Dawkins rhetorically. “Tell them they have to read 19th century American fiction for fun.”

Apart from this phenomenon of shoehorning high-achieving but young readers into books that technically match their level, the scores also cause problems for older students who struggle with reading. Dawkins points out that if every book in a school library is prominently labeled with a score, students who could benefit greatly from reading high-interest books that fall lower on the scale are often simply too embarrassed to be seen reading them.

Moreover, would-be censors sometimes seize on the discrepancy between a book’s reading level score and its suggested age range or grade level to justify removing it from a curriculum–as the superintendent of schools in Wallingford, Connecticut did with Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower in 2015. The issue is further complicated by the common assumption among parents that Lexile or AR scores also function like content ratings for profanity, sex, drug use, violence, or other mature themes. This is not the case, as Lexile customer support employees valiantly try to make clear in numerous FAQs on their website:

Lexile measures analyze the semantic and syntactic characteristics of a book, and do not describe the content of a book. Sometimes a Lexile measure by itself is not enough information to choose a particular book for a particular reader. Parents and educators should use their discretion to decide if a book’s content is age-appropriate for their readers.

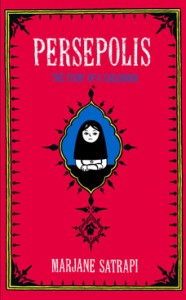

Comics and graphic novels are particularly susceptible to these misconceptions based on their assigned score. As Lexile also admits in explaining how it measures graphic novels, a purely text-based score cannot possibly take into account “the impact of picture support on reading comprehension.” The frequent result is that a graphic novel may be assigned an artificially low score, making it ‘off limits’ for students who can read at a high level but would still benefit from developing their visual literacy skills. For a striking example of this chasm, consider that Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi scores a 380 on the Lexile scale, putting the text alone at the reading level of an average 2nd grader. Anyone who’s read the book understands that as with any graphic novel, the images are not just supplemental to the text, but a vital component to actually comprehend the story. But going by the Lexile score alone, it would be nearly impossible to match a reader to the critically acclaimed modern classic.

As Dawkins concludes, reading level scores can certainly be one useful factor involved in selecting books for students to read. But too often, school administrators try to make it the only factor and effectively suck the joy out of reading for students, she says:

How do educators create a society of readers? It’s not by restricting reading to an accepted range of Lexile levels or only books that have a quiz attached to them. Reading levels can be a useful tool to assist in guiding a child to the right book for them, but when those numbers become the only determining factor of what is acceptable to read, we have a problem.

Dawkins also offers some tips for school librarians under pressure to limit students’ reading choices based on these measures. Check out her full post here at the OIF blog.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.