In 1971, American society was changing at such a rapid clip that the Comics Code Authority actually took notice and tried to keep up. Following a tumultuous decade of assassinations, riots, advances in civil rights, and increasing mistrust of government largely due to the Vietnam War, the first revision of the Code since its 1954 implementation allowed comics to inch somewhat closer to gritty reality. But among the many implied restrictions that remained: any mention of drugs, whether in a positive or negative light.

In 1971, American society was changing at such a rapid clip that the Comics Code Authority actually took notice and tried to keep up. Following a tumultuous decade of assassinations, riots, advances in civil rights, and increasing mistrust of government largely due to the Vietnam War, the first revision of the Code since its 1954 implementation allowed comics to inch somewhat closer to gritty reality. But among the many implied restrictions that remained: any mention of drugs, whether in a positive or negative light.

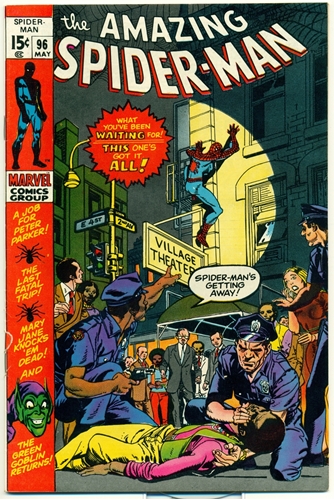

This week on the blog of ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, guest contributor and Pittsburgh librarian Tess Wilson covers the story of the infamous Amazing Spider-Man arc which was issued in the first half of 1971 without the Code seal because it included a subplot that dealt with drug abuse.

Never mind that according to Stan Lee, a government official from the National Institute of Mental Health had requested the storyline to raise awareness among young people–or that our hero Peter Parker definitely does not approve. (“My life as Spider-Man is probably as dangerous as any,” he observes in issue 96, “but I’d rather face a hundred super-villains than toss it away by getting hooked on hard drugs!”) According to the CCA, drug references were completely verboten and fell under Standards Part C:

All elements or techniques not specifically mentioned herein, but which are contrary to the spirit and intent of the code, and are considered violations of good taste or decency.

Nevertheless, Lee and Marvel took the daring step of releasing the three issues without approval–and as Lee wryly observes in his memoir Amazing Fantastic Incredible, “the world didn’t come crashing down.” Indeed, the rejection of the anti-drug storyline simply highlighted the absurdity of the Code, which was revised again that same year to clarify that drug addiction could be mentioned as long as it was portrayed “as a vicious habit.”

The defiant Spider-Man issues were actually written up in the New York Times, in a 1971 article now available online. There we see that while Comics Magazine Association of America president and Archie Comics publisher was willing to consider the drug-abuse arc to be Marvel’s “one slip” that he would allow to pass without sanction, DC publisher Carmine Infantino resented that his competitor seemed to skirt the rules:

You know that I will not in any shape or form put out a comic magazine without the proper authorities scrutinizing it so that it does not do any harm, not only to the industry but also to the children who read it. Until such a time, I will not bring out a drug book.

Indeed, DC did wait until shortly after the Code was revised again that year to address “the shocking truth about drugs” in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85. But without Lee and Marvel pushing the envelope, that revision might not have come about so soon!

Check out Wilson’s full post at OIF’s Intellectual Freedom Blog, as well as the contemporary New York Times article on the initial Code revisions and the Amazing Spider-Man arc. This story and its historical context were also explored in a 2012 post by CBLDF contributor Joe Sergi.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.