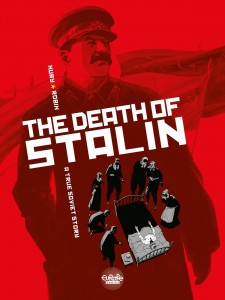

Last week Russian Ministry of Culture officials revoked the distribution license for Armando Iannucci’s satire, The Death of Stalin, based on the Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin’s graphic novel of the same name. When the Pioneer cinema in Moscow proceeded with screening anyhow, the movie theater was raided by armed Russian police and plainclothes investigators.

The movie and the graphic novel are about the death of Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union dictator who may be “ultimately responsible for the deaths of between 20 and 25 million people.” On March 1st, 1953, Stalin was found semi-conscious in his rooms and, because of intense fear and paranoia that Stalin himself created, his care was beyond terrible until his death on the 5th of March that year. Stalin left no clear successor, and no way in which to handle a succession, so it is easy to see how someone could devise a farce based on facts coinciding with his death.

The graphic novel opens with the following disclaimer:

Although inspired by real events, this book is nonetheless a work of fiction: artistic license has been used to construct a story from historical evidence that was at best patchy, at times partial, and often contradictory.

Having said this, the authors would like to make clear that their imaginations were scarcely stretched in the creation of this story, since it would have been impossible for them to come up with anything half so inane as the real events surrounding Stalin’s death.

The Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky said the ban on the film is not censorship,

We don’t have censorship.We are not afraid of critical and unpleasant assessments of our history, but there is a moral line between the critical analysis of our history and desecrating it.

And the history is of particular importance with the 75th anniversary of the victory of the Battle of Stalingrad falling on this Friday, February 2, 2018.

The Battle of Stalingrad “is often regarded as one of the single largest (nearly 2.2 million personnel) and bloodiest (1.7–2 million killed, wounded or captured) battles in the history of warfare.” Marshall Georgy Zhukov, portrayed in the film by Jason Isaacs, was integral to the win in Stalingrad, which was a major loss to Germany that is seen by many to have turned the tide in World War II.

Maria Zhukova, the daughter of Russian military giant Georgy Zhukov, portrayed in the film by Jason Isaacs, spoke with the Russian Military Historical Society,

This is a revolting film and a mockery of our history, our heroes, in particular of my father. The way in which all Soviet people are depicted is quite simply offensive. First of all for the descendants of those depicted in it and likewise for war veterans.

The Russian narrative is not different from the narrative common in America; both nations feel they saved the world from fascism and neither finds anything funny about that. So seeing Marshall Zhukov portrayed as a buffoon feels wrong to the Ministry of Culture. The disconnect comes from the fact the film isn’t mocking the war or the heroes in it, but rather mocking the chaos in a bizarre period of Russian history a decade later.

The irony is if they hadn’t banned the film, it probably would have passed by with less comment on it. Joy Neumeyer, a journalist and historian, noted,”Young people don’t care much about Stalin, but they have grown up with the ability to watch whatever they want.” They are clearly drawing more attention to it by prohibiting it, and the youth in Russia is well known for their myriad of piracy and torrent sites. So it’s a good bet that the ban isn’t actually prohibiting people from seeing it, so much as it is prohibiting people from paying for it.

This isn’t the first ham-fisted attempt at censorship by the Ministry of Culture in recent news. Earlier this year, they pushed back the opening of children’s movie Paddington 2 by a couple weeks to boost sales at Going Vertical and The Scythian, two movies made and financed in Russia. But this delay forced the cinemas to refund thousands of dollars for advanced tickets sales and the ministry of culture was un-shockingly unsympathetic, blaming the cinemas themselves for pre-selling tickets before acquiring their distribution license.

Neumeyer concludes:

By preening and scrambling like Jeffrey Tambor’s deputy Georgy Malenkov in The Death of Stalin, officials made Iannucci’s point about the buffoonery of power for him — an analogy that was not lost on audiences. “I think our chinovniki [bureaucrats] were outraged by the film because they recognised themselves in it,” a student who made it to one of the few screenings said.