Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in 2013 on Bleeding Cool after the CBLDF shirt was unveiled at SDCC. This year the author, Brian Puaca, has joined the CBLDF editorial team, and we decided to revisit this question, it being as relevant now as it was then.

Bill Gaines Was Right, Right?

by Brian M. Puaca

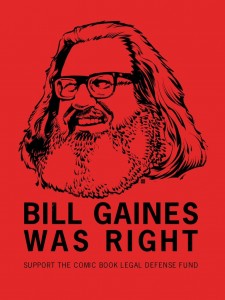

It’s hard to miss this Comic Book Legal Defense Fund shirt while walking the floor of comic conventions. The bright red shirt, featuring the publisher of EC Comics and creator of Mad Magazine late in his career, states simply “Bill Gaines Was Right.” While sharp-eyed fanboys might notice a strong similarity to a “Magneto Was Right” shirt that appeared in Grant Morrison’s New X-Men (#135), the red and black top might conjure more revolutionary connotations in the minds of others. This is only fitting, as Gaines was undoubtedly a trailblazer in the field of comics and fought fiercely against censorship for almost five decades.

Perhaps the most famous example of Gaines’s struggle against censorship is his testimony at the 1954 Senate Subcommittee Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency. Much has been written about Gaines’s appearance, the fact that he testified while taking diet pills, and the frustration of many of his colleagues in the field who believed he had done more harm than good. That said, the actual testimony from the hearing makes fascinating reading and offers a great number of insights into not only Gaines’s thinking but that of the subcommittee as well. Furthermore, it highlights the tensions felt by a superpower seeking to combat the spread of communism in the early days of the Cold War.

At the start of his testimony, the subcommittee permitted Gaines to read an opening statement in which he discussed the history of his company and its publications. In it, he made an impassioned plea for intellectual freedom and pushed his audience to look deeper into American society in order to identify the causes of juvenile delinquency. Gaines was quickly challenged by Herbert Beaser, chief counsel to the subcommittee, when he referenced the testimony of Fredric Wertham. Testifying immediately before Gaines, Wertham, a psychiatrist and outspoken critic of comic books, had pointed out multiple examples of violence, racism, and intolerance in EC publications. Gaines sought to use this opportunity to engage the subcommittee in a discussion of the content of his comics. In a brief exchange — in which, notably, not one senator on the subcommittee participated — Gaines pointed out the need for context when discussing his publications. He noted that the explicit purpose of the seemingly offensive language cited in the examples used by Wertham was to critique racism and to show the evils of prejudice and violence. Here Gaines was on solid footing, although it should also have been clear to him that these senators did not wish to engage in a debate about inequality in postwar America with a comic book publisher. (His next move, which was to suggest that censoring comic books would help turn the United States into Russia, probably did not help his case either.) Instead, the subcommittee asked him why, if children could draw positive messages from comic books, they could not also have negative effects. Unable to formulate a coherent response, Gaines never really recovered from this line of questioning.

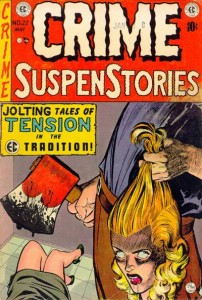

To answer the question posed in the title above, Gaines was right, but arguably for reasons different than those he actually offered in his testimony. Forced to comment on recent covers of EC publications before the subcommittee (famously Crime Suspenstories 22 and 23, which both depicted brutal murders), Gaines boxed himself into a corner when he defended his comic as being in “good taste.” This sparked a barrage of questions from his inquisitors that left Gaines nowhere to go. Was there any limit to what he would publish, they asked? “Only within the bounds of good taste.” In a follow-up question, Senator Kefauver noted that the cover of Crime Suspenstories 22 seemed “to be a man with a bloody ax holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?” Gaines said that it was in good taste for a horror comic. He countered that a cover in bad taste “might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be dripping blood from it and moving the body over a little further so that the neck could be seen to be bloody.” It is, however, hard to imagine that he actually believed that more blood dripping from the head of a decapitated woman would merit external censorship.

To answer the question posed in the title above, Gaines was right, but arguably for reasons different than those he actually offered in his testimony. Forced to comment on recent covers of EC publications before the subcommittee (famously Crime Suspenstories 22 and 23, which both depicted brutal murders), Gaines boxed himself into a corner when he defended his comic as being in “good taste.” This sparked a barrage of questions from his inquisitors that left Gaines nowhere to go. Was there any limit to what he would publish, they asked? “Only within the bounds of good taste.” In a follow-up question, Senator Kefauver noted that the cover of Crime Suspenstories 22 seemed “to be a man with a bloody ax holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?” Gaines said that it was in good taste for a horror comic. He countered that a cover in bad taste “might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be dripping blood from it and moving the body over a little further so that the neck could be seen to be bloody.” It is, however, hard to imagine that he actually believed that more blood dripping from the head of a decapitated woman would merit external censorship.

Indeed an earlier idea, mentioned by Gaines in his opening remarks, offered a more promising strategy for his testimony. Gaines stressed the fact that children were not simple-minded readers who emulated whatever they read in comic books. Young Americans, Gaines argued, had the ability to make decisions about their own lives, including what they read and how they conducted themselves. Furthermore, he emphasized the fact that children were also citizens, and that in this regard they, too, had rights that needed to be respected. This notion of citizenship — the word “citizen” appears only once in his entire testimony — is one to which not one senator responded. Quite the contrary is true, in fact, as Senator Robert Hendrickson (R-NJ) and Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN) made clear in their remarks at the start of the hearings that in no way did they wish to challenge or call into question basic rights of freedom of speech and the press.

Another interesting development comes in the last portion of Gaines’s testimony, when the subcommittee employed a rather subtle strategy to further discredit him. The senators posed several questions to Gaines regarding the circulation of his comics, total sales, advertising revenues, and his salary. At first glance, one might believe that the questions were intended to highlight the influence of EC Comics in terms of sales figures. A more careful reading, however, reveals what seems to be a more subtle strategy designed to further undermine Gaines’s reputation. The tone of the questioning suggests that the subcommittee sought to portray Gaines as a crass businessman whose amoral (or perhaps immoral) practices endangered young Americans. This is particularly ironic at a time when the United States was engaged in an effort to spread American business practices throughout western Europe and elsewhere. To indict a comics publisher for making money illustrates both the serpentine strategy of the subcommittee as well as a more general insecurity about prosperity in American society.

The Cold War context in which the subcommittee operated is worth remembering. At a time when America feared the Soviet Union and the spread of communism, many perceived juvenile delinquency to be a threat to national security. The fact that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI had only recently released data showing significant increases in crime, especially among young Americans, only further heightened the anxieties of parents, teachers, and lawmakers. At the same time, the CBLDF shirt is not designed merely to commemorate Gaines and his past efforts to protect the comics medium at a particularly dangerous time in its history, important though they might have been. The shirt also serves to highlight the contemporary relevance of Gaines’s efforts and ongoing challenges to those comic creators who challenge readers. One only needs to think of recent efforts to ban Drama and Fun Home to be reminded that the debate continues.

To learn more about Bill Gaines, check out CBLDF’s Charles Brownstein at the Library of Congress.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Brian M. Puaca is an associate professor of history at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, where he teaches a course on the history of comic books and American society. He can be reached at bpuacaATcnu.edu