This week marked the 4th anniversary of the gruesome Charlie Hedbo attack, where two brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, forced their way into the newspaper’s office and killed 12 people, injuring 11 more. At the time of the tragedy, the world was horrified by the violence against the paper – a rally for national unity took place less than a week later with 40 world leaders present as part of the group of 2 million, and an additional 3.7 million joining in demonstrations all across France, everyone chanting “Je suis Charlie” or “We are Charlie.” Now four years later, we look back in sadness at these attacks and wonder, are we still all Charlie? Or was this attack just the beginning of the normalization of violence against the press that we are still deeply in the dark about.

This week marked the 4th anniversary of the gruesome Charlie Hedbo attack, where two brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, forced their way into the newspaper’s office and killed 12 people, injuring 11 more. At the time of the tragedy, the world was horrified by the violence against the paper – a rally for national unity took place less than a week later with 40 world leaders present as part of the group of 2 million, and an additional 3.7 million joining in demonstrations all across France, everyone chanting “Je suis Charlie” or “We are Charlie.” Now four years later, we look back in sadness at these attacks and wonder, are we still all Charlie? Or was this attack just the beginning of the normalization of violence against the press that we are still deeply in the dark about.

The morning of the attack, January 7 2015, the staff of Charlie Hedbo was gathered getting ready for the first editorial meeting of the new year in the unmarked work space they had moved to after their previous office was firebombed four years earlier. The two gunmen, initially having entered the wrong location looking for the newspaper, found the correct building and encountered cartoonist Corinne “Coco” Rey. The men threatened Rey to get her to open the locked door.

The brothers entered, firing a spray of bullets through the lobby, killing Frédéric Boisseau, a maintenance worker. They then forced Rey at gunpoint to take them to the editorial meeting still underway upstairs. Once they entered, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi began calling out for Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier), the director of Charlie Hedbo, to identify himself and then shooting people in the meeting. Rey was able to survive the attack by hiding under a desk after the Kouachi’s started murdering the journalists one by one. Rey watched the murder of Georges Wolinski and Jean Cabu, two of her fellow cartoonists, from her hiding place. Reporter Laurent Léger also survived by hiding under a desk, while crime reporter Sigolène Vinson survived after one of the two killers told her he wouldn’t shoot her because she was a woman. That didn’t stop them from murdering Elsa Cayat, a psychoanalyst and columnist of Tunisian Jewish descent who was the only woman killed in that attack.

Other people killed in the attack include Franck Brinsolaro, Charb’s assigned bodyguard; Bernard Maris, editor, columnist, and economist; Mustapha Ourrad, copy editor; Michel Renaud, a travel writer visiting Charb; Ahmed Merabet, police officer killed outside of the offices; and cartoonists Philippe Honorè, Tignous, and, of course, Charb himself.

Saïd and Chérif Kouachi escaped the offices and began running from the mounting manhunt aimed at apprehending them. On January 9th, the brothers fled into an industrial group of buildings. Armed French police surrounded the compound and the siege last for nearly nine hours before the brothers ran out and opened fire onto the officers, successfully martyring themselves as was their desire. Across town an ally of the Kouachi brothers, Amedy Coulibaly, had taken hostages in a kosher supermarket, telling police he would kill his hostages if the brothers were harmed at the other siege. Coulibaly died within minutes of the Kouachi brothers, who he had reportedly been in contact with during the siege.

Just last month in December 2018, Peter Cherif was arrested by French authorities for playing a crucial role organizing the attacks on Charlie Hedbo. Cherif had been eluding French custody since 2011, when he fled right before being sentenced to five years in prison on unrelated terrorism charges.

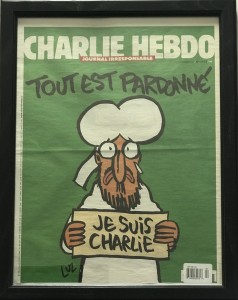

The next issue of Charlie Hedbo following the attack, 1178, which ran the now-iconic cover of Muhammad with a sign reading “Je suis Charlie,” was put together by the surviving staff in the office of another French newspaper, Libèration. Normally an issue of Charlie Hedbo would have a print run of 60,000 copies. 1178 had a print run of 7.95 million copies, making it a record breaking publication for not just Charlie Hedbo but the entire nation of France.

The next issue of Charlie Hedbo following the attack, 1178, which ran the now-iconic cover of Muhammad with a sign reading “Je suis Charlie,” was put together by the surviving staff in the office of another French newspaper, Libèration. Normally an issue of Charlie Hedbo would have a print run of 60,000 copies. 1178 had a print run of 7.95 million copies, making it a record breaking publication for not just Charlie Hedbo but the entire nation of France.

The solidarity felt after the shooting was in no means absolute. there were many who participated in victim-blaming, accusing the staff of Charlie Hedbo of being responsible for their own violent deaths for publishing satire that some deemed offensive. There were massive protests in Yemen, Pakistan, Algeria, Senegal, Niger – where the protests were so violent that there were 10 fatalities – and many other places around the world.

122 Journalists have been murdered, including the ones who worked for Charlie Hedbo, since 2015. 2018 was the deadliest year yet, with at least 34 confirmed murders including journalists killed in the mass shooting at The Capitol Gazette in Annapolis, Maryland and the murder and dismemberment of Washington Post reporter Jamal Khashoggi. But now there are no protests and there is no unity. Despite Time magazine’s declaration that the people of the year for 2018 are The Guardians of Truth, those out there reporting regardless of concerns for their own freedom and safety, it seems at every turn people in power are railing against the straw man of “fake news.” This is the new normal. So now when people think, “Je suis Charlie” – are they thinking about solidarity with a media under constant attack for exercising free speech? Or does the phrase “We are Charlie” mean something darker now? That the whole of journalism is now Charlie Hedbo – under fire for utilizing the free press too many take for granted?

If you want to do your part to support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2019, please consider visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!