In celebration of Black History, CBLDF is rerunning some amazing profiles created in partnership with Black Nerd Problems to spotlight Black comics creators and cartoonists who made significant contributions to free expression. To see the full list of resources, visit https://cbldf.org/profiles-in-black-cartooning/

Profiles in Black Cartooning: Bertram A. Fitzgerald and Golden Legacy

This is the story of a mild-mannered accountant, Bertram A. Fitzgerald, who unexpectedly became a pioneer in comics publishing. At a time when the field of African American Studies was largely confined to academia, Fitzgerald saw the pedagogical potential of both the comics format and Black history as a means to engage youth who had seldom seen themselves reflected in their history books.

Growing up in Harlem in the 1930s and ‘40s, Fitzgerald was an avid reader of history and classic literature. Among the books he devoured were the Classics Illustrated series of comic adaptations, but he later came to realize that the African heritage of authors such as Alexander Pushkin and Alexandre Dumas had been completely omitted in the short biographies included in the books.

Despite this lack of representation in the mainstream press, Fitzgerald developed an interest in Black history thanks to his seventh grade history teacher, who noticed his students were more engaged when the curriculum included the contributions of people of African descent in all eras and sectors of society, rather than just a brief unit on slavery. That history class, Fitzgerald later told the New York Times, “was like an elixir. Like a shot in the arm. It made the Constitution true for me.”

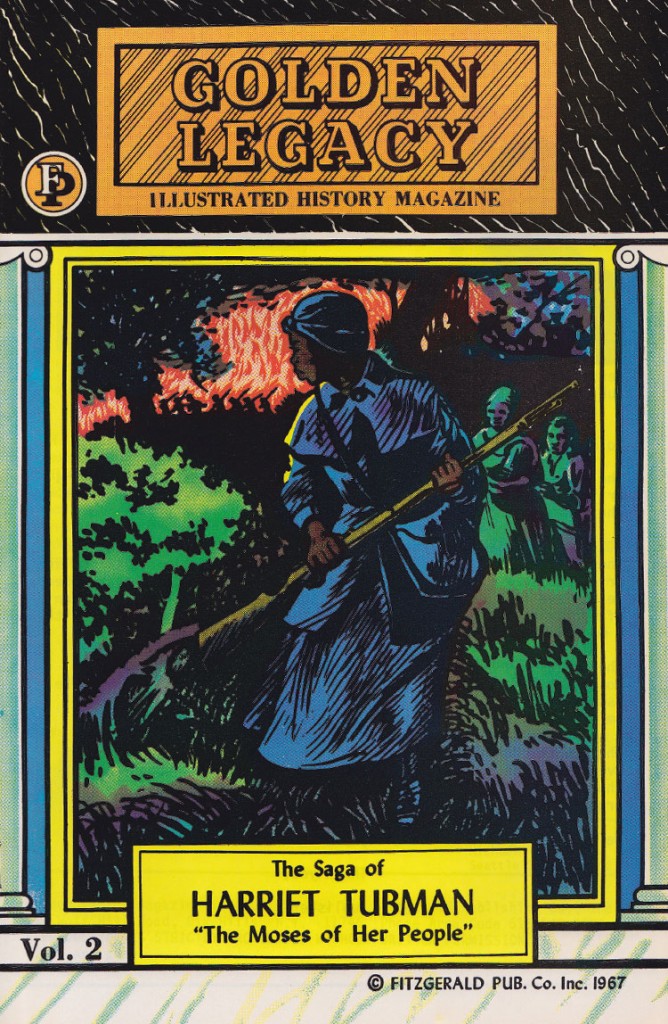

After serving in the Air Force and earning a degree from Brooklyn College in 1953, Fitzgerald became an accountant, eventually working for the New York State Department of Taxation and Finance. In the mid-1960s, when Black history was still largely neglected in schools, he struck upon the idea of producing comic-style biographies of the people who so inspired him in his youth. Finding no interest from any established publishing companies, however, he was obliged to start his own. Golden Legacy Illustrated History Magazine Vol. 1, about Haitian Revolution hero Toussaint L’Ouverture, appeared in 1966 with text by Fitzgerald himself and art by Leo Carty.

For distribution of the early issues, Fitzgerald relied on the specialized sales market that already existed for products geared toward Black customers, such as hair products, makeup, and stockings. He found it difficult to get paid through these small and varied distribution channels, however, and by Volume 3 in 1967 he used his business savvy to strike a plum deal with the Coca-Cola Company. The soda giant got the prime ad space on the back of every Golden Legacy volume, and in return the company paid Fitzgerald’s printing costs. As part of its marketing in Black communities, Coke also bought wholesale bundles of each issue and distributed copies for free in schools, libraries, and local chapters of the NAACP and the Urban League. This arrangement lasted until Volume 11 in 1970, after which Fitzgerald negotiated similar deals with other major companies including AT&T, Avon, McDonald’s, and Columbia Pictures.

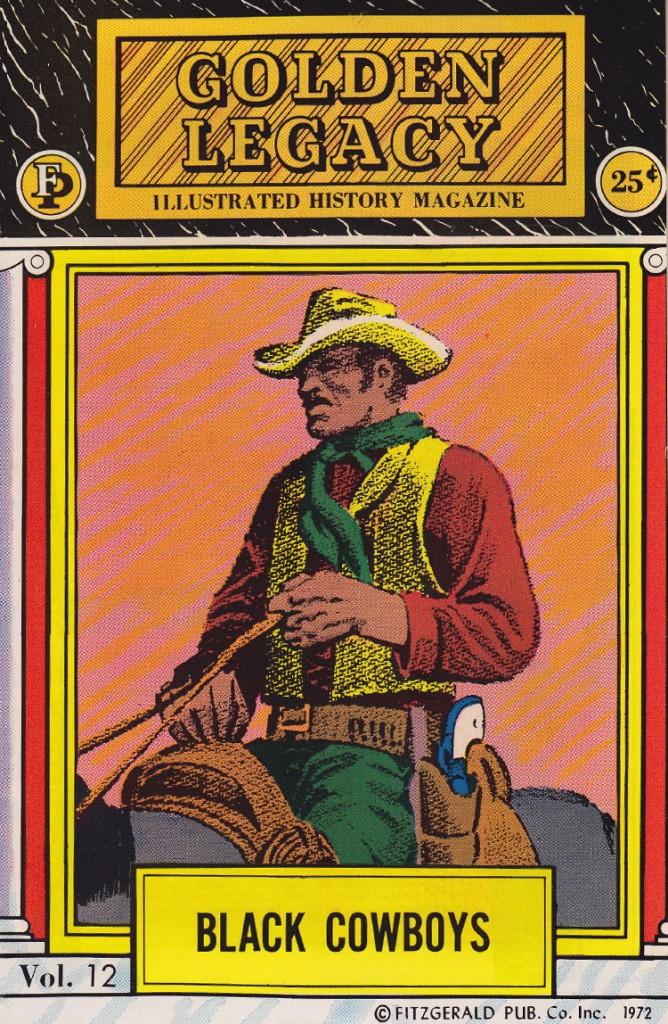

Over a decade of publishing, Fitzgerald produced a total of 16 Golden Legacy volumes about figures from Harriet Tubman to Alexander Pushkin to Martin Luther King, Jr. By the 1970s and ‘80s, Black history finally began to be integrated into curricula, so schools and libraries were buying full sets of Golden Legacy. Fitzgerald was enormously gratified to see more students getting exposure to their own history, later telling the New York Times that “if there is nothing to counter the negativism that you read, which is fully covered, you will get the impression…that there were no contributions by blacks. You feel kind of small.”

Tragically, the success of Golden Legacy came to a screeching halt in 1983 when another publisher named Bill R. Baylor managed to convince Fitzgerald’s printer that he had bought the business from Fitzgerald, which was untrue. The printer relinquished the original plates and negatives to Baylor, who commenced printing Golden Legacy with his own name attached. Fitzgerald sued for copyright infringement and eventually won, but not before a five-year court battle, during which he suffered two heart attacks. In 1988 he finally got the negatives back and was at least able to publish his own books again, but Baylor had disappeared and Fitzgerald never got the damages he’d been awarded by the court.

According to a 1989 profile from Black Enterprise magazine, Fitzgerald had plans for nine more Golden Legacy volumes including Sojourner Truth, W.E.B. Dubois, and Marcus Garvey. Those never materialized, but the original 16 volumes are still sold through Golden Legacy’s website. After the lawsuit was finally resolved, Fitzgerald returned to accountancy full-time, though he still served as publisher of Golden Legacy. He passed away at the age of 84, in 2017, but as his obituary concluded, his “legacy will itself live on in the lives and attitudes of the black youth he lovingly tried to reach.”

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2019 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

CBLDF Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.