By Nora Flanagan

Welcome to Using Graphic Novels in Education, an ongoing feature from CBLDF that is designed to allay confusion around the content of graphic novels and to help parents and teachers raise readers. In this column, we examine graphic novels, including those that have been targeted by censors, and provide teaching and discussion suggestions for the use of such books in classrooms.

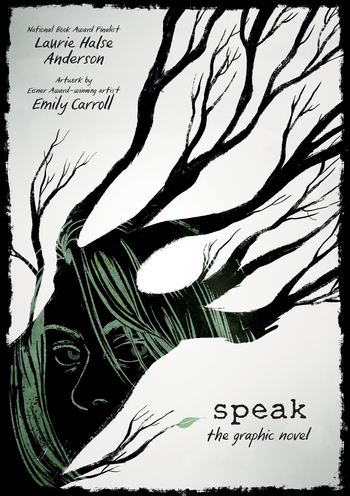

April, as Sexual Assault Awareness month, offers a chance to explore an important addition to the comics world, Speak: The Graphic Novel, by Laurie Halse Anderson and illustrated by Emily Carroll (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018). We’ll look at its themes, merits, causes for concern, opportunities for classroom discussion and activities, and additional resources available to support this text.

OVERVIEW

When Speak, by Laurie Halse Anderson, was released as a novel in 1999, its frank prose and relatable narrator resonated immediately. Teachers, librarians, and parents alike watched young people, especially young women, tear through it and then pass it right along to friends they thought also needed to read Speak. Speak would go on to become a National Book Award Finalist, an American Library Association Best Book for Young Adults, and a Golden Kite Award winner, among many other honors over the years since its release. The book’s power with its audience hasn’t faded; nor have the objections to its direct discussion of sexual assault.

To call Emily Carroll’s visual adaptation of Speak ‘powerful’ would be a staggering understatement. Carroll’s use of negative space, nonstandard panel arrangement, inner monologue, and the flashback story arc central to the original novel collaborate to absorb the reader into Melinda’s battle to find her voice and her place as a high school freshman trying to recover from a sexual assault the previous summer. Speak: The Graphic Novel offers a broad range of classroom opportunities for thematic discussion, close study of comics as a narrative medium, interdisciplinary research, and more.

This adaptation has already garnered a number of honors. Speak: The Graphic Novel is a School Library Journal Best Book of 2018, a 2019 selection as an Amelia Bloomer Best Feminist Book for Young Readers, and a nominee for both the Eisner and the Edgar Allen Poe Awards, among others. The publisher’s recommended age range for this book is 12-18.

Main Characters:

- Melinda

- Melinda’s parents

- Rachel, her former best friend

- Nicole, another former friend

- Heather, her new fair-weather friend

- Melinda’s teachers: “Mr. Neck,” “Hairwoman,” Mr. Freeman

- David Petrakis, her inspiring classmate

- Andy Evans

Themes:

- Sexual violence

- Communication barriers

- Friendships, cliques, and bullying

- Teachers and teaching

- School policies

- Family tensions

- Mental health

- Art as therapy

- Students standing up to authority

SUMMARY

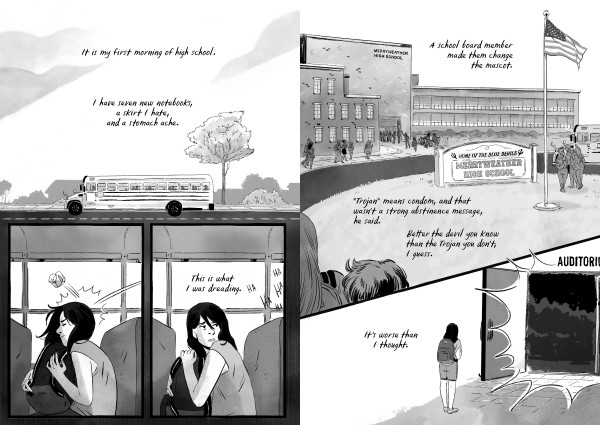

Speak: The Graphic Novel follows the format of the original novel very closely: the book as a whole is divided into the four marking periods of the main character’s freshman year of high school, and those sections are subdivided into short vignettes with titles ranging from literal (“The Marthas”) to ironic and sarcastic (“Our Teachers Are the BEST!” and “Giving Thanks”).

First Marking Period

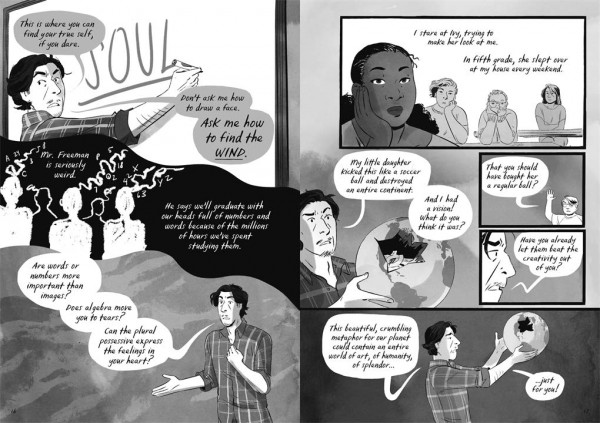

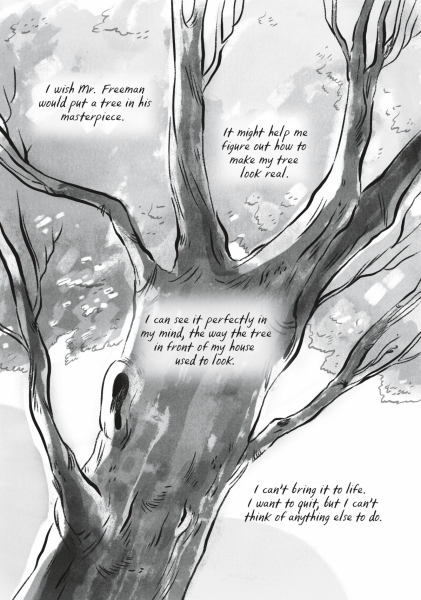

Melinda is an outcast at her new high school; whispers and hostility follow her as soon as she enters the building. She learns quickly that “It is easier not to say anything. Shut your trap, button your lip, zip it.” This introduces a main conflict of the novel: Melinda’s fight to find her voice. She is intrigued, but also a little overwhelmed, by her art class, in which the teacher assigns a subject theme for the year — Melinda gets trees as her theme — and tells his students, “Welcome to the only class that will teach you how to survive.”

Melinda continues to experience targeted bullying, beyond what even the most oblivious adult could excuse as ‘normal’: she is tripped, shoved, mocked, and excluded at every turn, including by the girls who were her closest friends in elementary school the year before. Melinda’s only company is a new student named Heather, who desperately tries to fit in, make friends, and join activities. Melinda is exhausted enough by the mere act of survival. As a result, she rarely does any schoolwork. To avoid bullying and schoolwork, she furnishes a janitor’s closet as a hiding spot.

We see the first indications of self-harm in this section, as Melinda bites her lips until they are bloody and ragged. We learn that Melinda is a target because she called the police about a party that summer, leading to arrests for some in attendance. Melinda alludes to more having happened, but feels she can’t tell anyone. The section ends with Melinda encountering a male student she refers to as “It” who attends Merryweather and clearly terrifies her.

Second Marking Period

Melinda is incrementally shutting down, spending more time in her closet at school and feeling increasingly distant from Heather, her parents, and her classes. At home, Thanksgiving goes disastrously. Melinda’s parents descend quickly into arguing, and Melinda is overlooked. While the turkey ends up inedible, Melinda makes some inspired art out of its wishbone and some dismantled doll parts.

By Christmas, Melinda is sure she’s invisible to everyone, but her parents give her art supplies as gifts because they noticed how much she’s been drawing. Melinda wishes she “could tell them what happened,” but ultimately feels she can’t.

As unhinged as he might occasionally seem, Mr. Freeman and the space he creates in his art class continue to offer Melinda reprieve and a sense of safety. She is inspired by his resistance to school authorities, too, much like her classmate David’s protests against their bigoted history teacher. A frog dissection in biology class sends Melinda back to that night at the party, and she passes out. Soon after, we see that Melinda has been cutting herself and thinking about suicide, but she still feels unable to ask for help. She has two run-ins with the young man she has called “It,” whose real name is Andy Evans. He bullies Melinda, too, but more intimately, and his presence sickens Melinda. Her grades have dropped further, and her parents are enraged at this point.

Third Marking Period

Melinda sees more reasons not to speak up — to classmates, at home; even art class feels less welcoming, as her teacher continues his fight against the school board. To make matters worse, Heather breaks off her friendship with Melinda, now that she has finally found a clique. Heather blames Melinda’s depression, and Melinda realizes that her half-hearted friendship with Heather was the only social connection she had.

A meeting at school, in which Melinda’s parents argue and school officials offer little help, leaves her feeling even more alone and unheard. A chance conversation soon after with Mr. Freeman helps, though. He tells her, “When people don’t express themselves, they die one piece at a time. It’s the saddest thing I know.”

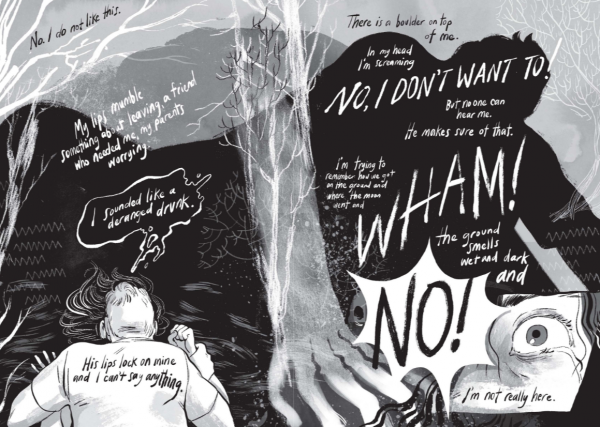

This section ends with Melinda sitting outside in the snow and remembering in detail what happened at the party last summer. She recounts drinking her first few beers, wandering outside, and flirting with a boy. They kiss, and she’s excited for what feels like a scene out of a high school romance, but things grow increasingly aggressive and frightening, and he doesn’t listen to her when she indicates she doesn’t want this. He holds her down, covers her mouth, and rapes her. She wanders back into the party and calls the police in a traumatized daze. People at the party realize what she has done, but they have no idea what has just happened to her.

Fourth Marking Period

Home sick with a fever, Melinda finally acknowledges that she was raped.

Melinda panics when she realizes her former best friend, Rachel, is now dating Andy Evans. Melinda tries telling Rachel, what Andy Evans did to her, but Rachel refuses to believe her and presumably tells Andy. After an encouraging conversation with another former friend, Melinda writes a warning about Andy Evans on the bathroom wall at school.

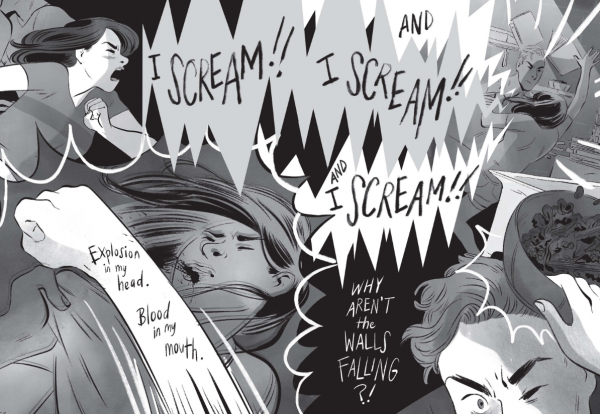

In one of the book’s last scenes, Melinda finds herself trapped in her closet hiding place with Andy after he follows her there. He attacks her, blaming her for his increasing notoriety among classmates as a rapist. Melinda fights back this time; she screams loudly while defending herself to the extent of holding a sharp object to his neck, just as others hear what is happening and start pounding on the door to help her.

The book concludes with Melinda realizing that her rape did not define or end her, and she will continue to grow, emerge, and speak.

TEACHING AND DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS

For Women’s History Month

- Research the #MeToo movement in mass media and politics. How did it begin? How did it gain and maintain momentum? What have been its outcomes so far? Reflecting on these questions, how is it similar to and different from previous protest movements around women’s rights?

- Bonus: Research and discuss Laurie Halse Anderson’s response to #MeToo.

- Melinda adds a poster of Maya Angelou to her hideout closet at school. One of Maya Angelou’s most famous works is I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, an autobiographical narrative that includes an account of experiencing sexual assault. What other women writers have included sexual assault stories in their work? How has it been received? (Hint: On page 79, Melinda mentions that one of Maya Angelou’s books has been banned at her school….)

Critical Reading and Making Inferences

- Emily Carroll draws Melinda often reacting silently to the words of others. What should we infer from these depictions? What do the author and artist want us to see or feel about Melinda’s silence?

- Melinda’s friendship with Heather is nuanced and complicated; we’re not sure if Melinda even likes Heather sometimes. Why does she spend so much time with Heather, including helping her win over a new group of friends? Reread the scene when Heather tells Melinda she doesn’t want to be friends anymore (182–186). Heather says, “We were never really really friends, were we?” Is Heather right in saying this? Why or why not?

- On page 217, Melinda calls out the double standards presented to women about their bodies and appearances. Explain the contradictions in your own words. Research more on this issue: how are young women speaking up about body shaming and expectations about their appearances? How does this issue impact young men, too? Find another point in the book when Melinda spots and highlights hypocrisy.

- Speak: The Graphic Novel levels focused criticism at Melinda’s school for failing to support her, or even to see her, while she was struggling with a mental health crisis. Find instances in the narrative when the school missed an opportunity to reach out to Melinda more effectively. What could staff members have done better? What changes could a school like Merryweather make to be more responsive to students in crisis? What resources are available at your school or in your community?

- One minor subplot involves the school’s ongoing dilemma of its mascot. Does this have anything to do with any of the larger themes in Speak: The Graphic Novel? How? Research a school mascot conflict from within the past few years, and find quotes from students involved on each side of the issue.

Language, Literature, and Language Usage

- Trees figure prominently in the imagery throughout Speak: The Graphic Novel. How does Melinda’s selection of a tree as her art theme for the year reflect her struggles? How is a tree representative of what she experiences throughout the year? Consider different possible tones for this question, and find panels and sequences that support your ideas.

- Animals also factor into the storytelling often, and Melinda interacts with them in a range of ways: the frog dissection (136), the bird Melinda sees as part of a flashback on her day off from school (175), the bunnies (231), even the turkey that ends up inedible on Thanksgiving (90). Is there any pattern to their purpose? How do the author and artist collaborate to anthropomorphize animals throughout the narrative?

- The author and artist emphasize sensory images throughout Speak: The Graphic Novel — smells, sounds, even the sensation of weight on Melinda is used to describe and depict different ways she feels. Find examples of this and note how the author and artist collaborated on these sensory images at key moments.

Modes of Storytelling and Visual Literacy

- Flashbacks: How does the author and artist’s use of flashback slowly reveal what has happened to Melinda impact our experience with the book? Find a point in the narrative when the timeline switches back to the summer before high school. How did Laurie Halse Anderson and Emily Carroll indicate these flashbacks? How would the book feel different if we were given the entire narrative of Melinda’s assault at the beginning of the book?

- Visual depictions of character traits: Choose one physical trait of a character and find panels where the artist highlights this trait. Identify the trait, and analyze choices made by the artist to bring this trait forward. Next, choose a non-physical trait of a character, and repeat this exercise.

- Panels: After viewing examples of classic panel layouts in comic books and graphic novels, find examples in Speak: The Graphic Novel where Emily Carroll chose asymmetrical panel layouts, single-panel pages, and other unusual ways to visually divide up a page of narrative. Why might she have done this? How does it impact these moments in the narrative?

- Panel project: students should tell a brief story (or create a scene) on one page of traditionally divided comic panels. Then they should rebuild their stories using floating panels, bleeds, and other nonstandard arrangements as demonstrated in Speak. How do these choices impact their stories? This task can also be completed with students retelling an existing page of another graphic novel or comic book with more traditional panel arrangement.

- Bleeds: Find examples in the book when the visual images go all the way to the edge of the page. In comics, this is called a ‘bleed.’ Are there any patterns in the moments the artists depicts using bleeds? How do they impact the storytelling in Speak: The Graphic Novel? How do they change the feel or mood of a page?

- Expressionism: Emily Carroll often projects Melinda’s moods and anxieties onto depictions of other characters. As a visual arts movement, Expressionism encourages distortion in visual imagery to convey tension and emotion, as in Edvard Munch’s The Scream; Mad Woman, by Chaim Soutine; or Portrait of a Girl, by Gabriele Münter. Find an example in Speak: The Graphic Novel of a character’s features drawn in a distorted and figurative way to reflect Melinda’s state of mind. What do we learn from these depictions?

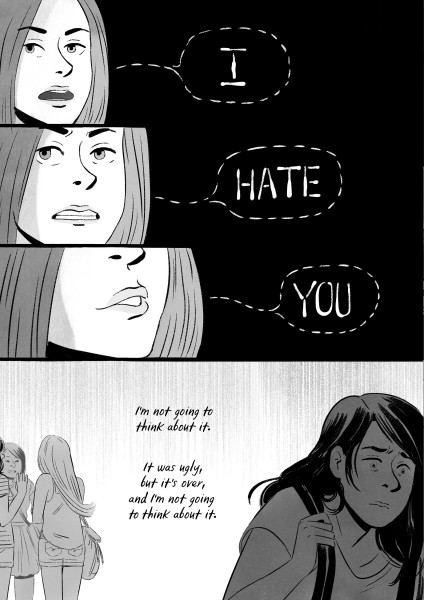

- Negative space: When artists use negative space, the background is darkened and the image we are meant to notice emerges in white or lighter tones. We see an early example of this in Speak: The Graphic Novel when Rachel mouths “I HATE YOU” to Melinda in the chapter titled “Welcome to Merryweather.” Alone or with a partner, find three more examples of negative space in Speak: The Graphic Novel (there are many), and try to speculate a purpose for its overall use in the book. What kind of moments does Emily Carroll choose for this technique? What impact does it have on our perception of these moments?

Cultural Diversity, Civic Responsibilities, and Social Issues

- Melinda’s school surveys the students about what mascot they prefer, but they don’t seem good at listening about issues that matter. How can schools amplify student voices around policy decisions, safety problems, and student wellness issues?

- Melinda’s classmate, David Petrakis, stands up to a teacher who is bullying his students with racist and xenophobic tirades. How can schools support students who have concerns about these issues in their school community? How does David’s conflict with their teacher influence Melinda?

- Research sexual assault statistics at the high school and college level. What percentage of assaults do experts believe get reported? What factors might determine if an assault gets reported or not? What steps can schools, police departments, and other entities take to increase the likelihood that a victim will report an assault?

Suggested Prose Novel and Poetry Pairings

- Speak, by Laurie Halse Anderson

- Shout, by Laurie Halse Anderson — The author’s poetic memoir includes formative experiences and observations as a young woman, how she survived sexual assault, and why she came to write Speak.

- In the Dreamhouse, by Carmen Maria Machado — this memoir, widely praised and highly inventive, chronicles the author’s experience in an abusive relationship.

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, by Maya Angelou — Autobiographical account of Maya Angelou’s early life.

- “Caged Bird,” by Maya Angelou — this poem was written long after the publication of the book whose title is similar; it describes the challenges faced by a bird who cannot sing out freely.

- “Windigo,” by Louise Erdrich — this poem describes a mythical beast that menaces young girls.

- “I Wish I Want I Need,” by Gail Mazur — this poem talks about complicated communication, in both romantic and mother-daughter relationships.

- “A Man’s Requirements,” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning — while interpretable a number of ways, many read this poem as an effusive love poem with a twist at the end, leaving us with a commentary on relationship expectations versus reality.

- Because I Am Furniture, by Thalia Chaltas — A young woman learns to find her voice and her strength in an abusive household in this young adult novel.

- The Hate U Give, by Angie Thomas, also includes themes of powerlessness for its young woman protagonist. In the novel, Starr must learn to speak up against police violence after losing a dear friend, and her journey includes difficulties in her school community as she navigates this loss and its ensuing conflicts.

- Young women are consuming poetry more than any other demographic group. Here are a bunch to check out, according to Bustle. Encourage students to find poetry that speaks to Melinda’s story.

- We Believe You: Survivors Campus Sexual Assault Speak Out, by Annie E. Clark and Andrea L. Pino

Common Core State Standards

The graphic novel format provides verbal and visual storytelling, which not only addresses multi-modal teaching, but also meets the following Common Core State Standards:

- Knowledge of Language: Apply knowledge of language to understand how language functions in different contexts, to make effective choices for meaning or style, to comprehend more fully when reading or listening.

- Vocabulary Acquisition and Use: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases by using context clues, analyzing meaningful word parts, and consulting general and specialized reference materials; demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meaning; acquire and use accurately a range of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases sufficient for reading, writing, speaking and listening at the college and career readiness level.

- Key ideas and details: Reading closely to determine what the texts says explicitly and making logical inferences from it; citing specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text; determining central ideas or themes and analyzing their development; summarizing the key supporting details and ideas; analyzing how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of the text.

- Craft and structure: Interpreting words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings and analyzing how specific word choices shape meaning or tone; analyzing the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs and larger portions of the text relate to each other and the whole; assessing how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

- Integration of knowledge and ideas: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually as well as in words; delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence; analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

- Range of reading and level of text complexity: Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently.

- Research to Build and Present Knowledge: Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation; gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of each source, and integrate the information while avoiding plagiarism; draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- Comprehension and collaboration: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively; integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively and orally; evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

- Presentation of knowledge and ideas: Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization; adapt speech to a variety of contexts and communicative tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

- Discussion Guide from the publisher

- Teacher’s Guide from the publisher

- An Educator’s Guide to Laurie Halse Anderson: Building Resilience Through Young Adult Literature (Penguin)

- “The Voice of Speak Is Loud as Ever” (author interview in The Atlantic, 2012)

- RAINN — the nation’s largest organization to fight sexual violence.