by Brian M. Puaca

As popular anxieties regarding comic books intensified after World War II, the federal government decided to enter the fray in 1954 by holding Congressional hearings to investigate the link between the four-color publications and juvenile delinquency. Throughout these hearings, elected officials claimed that they had no interest in censoring comic books and stressed their support of the First Amendment. Publishers, however, were deeply worried about possible federal restrictions on their products, and within months, banded together to introduce the Comics Code Authority as a tool of self-censorship. Indeed, the mere suggestion of federal involvement – a threat that never materialized – mobilized the industry into action. This fear was justified, and some of the publishers may have recalled that the government had already gone after comics a few years earlier.

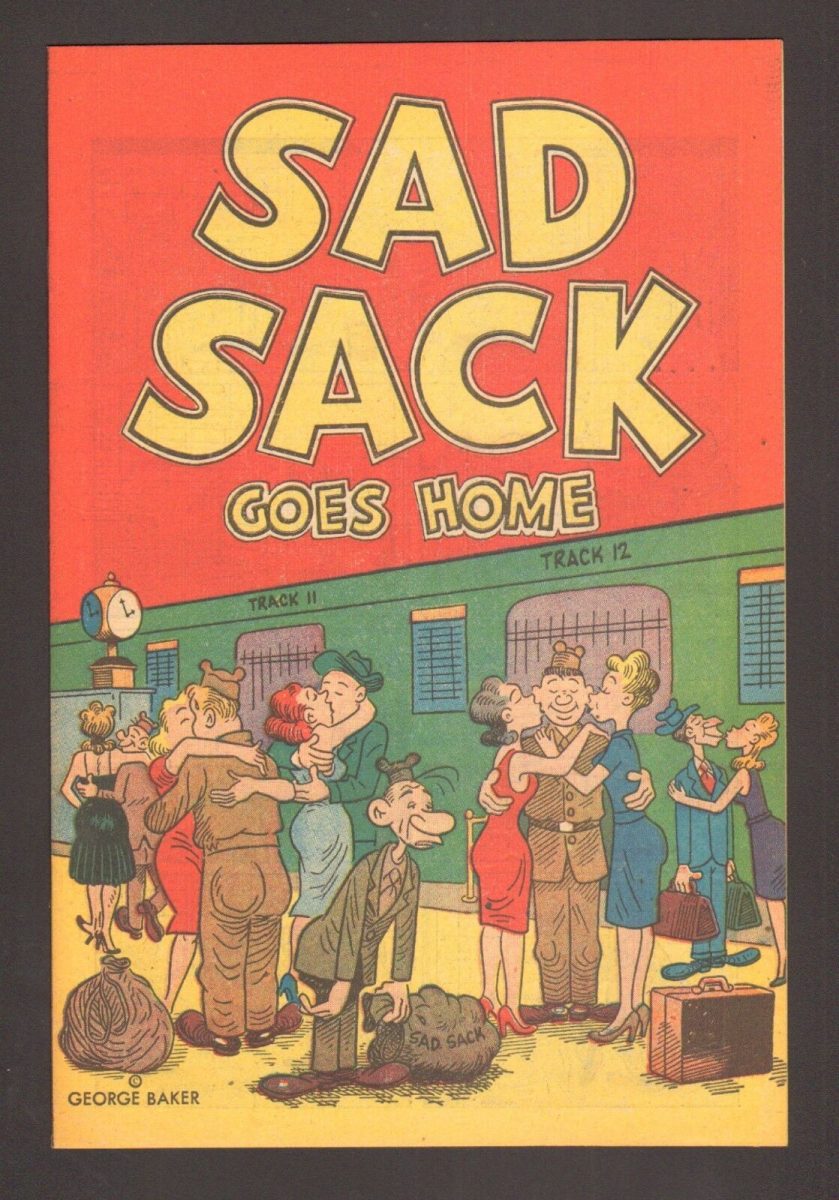

Three years prior to the infamous Senate Subcommittee Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency, the U.S. government engaged in a largely forgotten war with a comics hero of its own making. George Baker’s Sad Sack had premiered in the first issue of the weekly Armed Forces tabloid Yank in 1942, and the character was an immediate success. Enlisted men identified with the struggles of the downtrodden and luckless soldier who consistently found himself in trouble with superiors, baffled by Army bureaucracy, or simply frustrated with his daily predicament. Sad Sack had proven so popular with soldiers that he was used to encourage subscriptions to Yank during World War II, and the U.S. Army sent Baker to bases around the world to find material for his satirical (and usually silent) stories. Sad Sack continued to appeal to older readers, especially veterans, after the war; he received a regular Sunday newspaper strip in 1946 and appeared in a new comic book series published by Harvey Comics in 1949. By the early 1950s, Sad Sack’s Sunday strip appeared in ninety newspapers across the country.

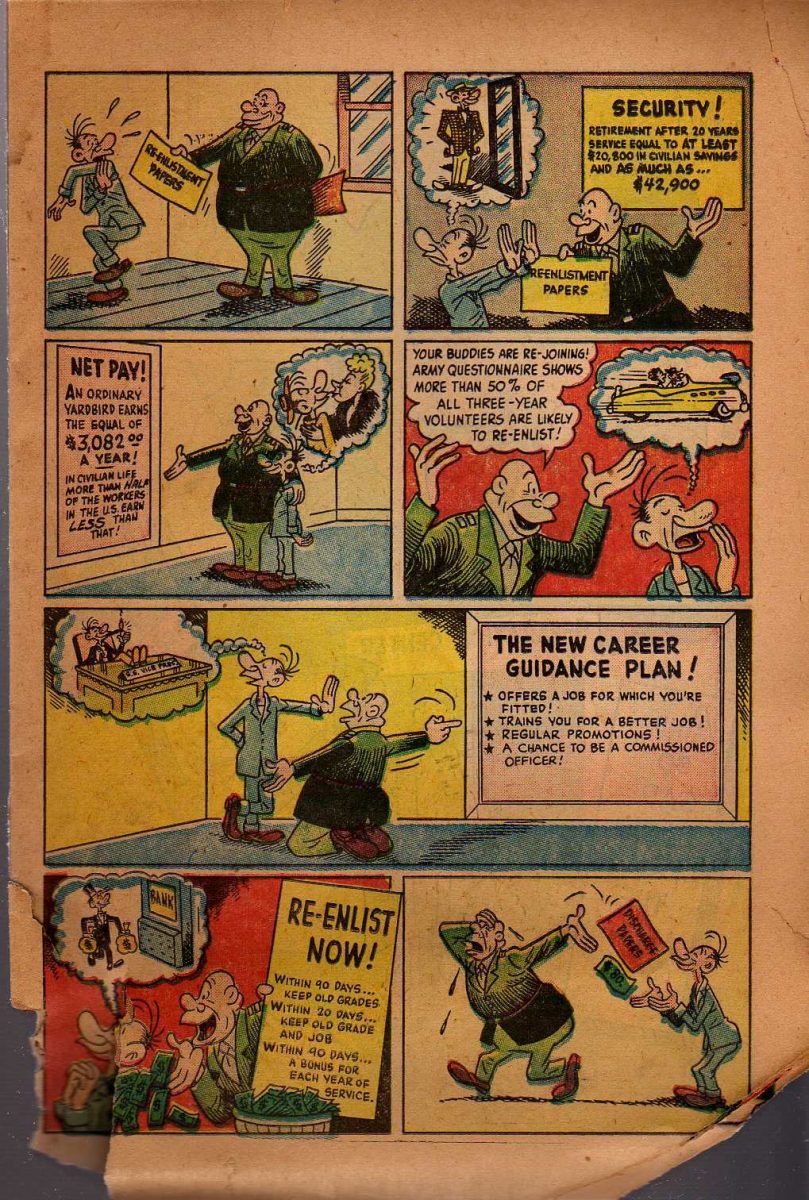

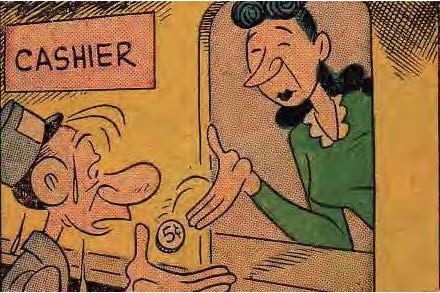

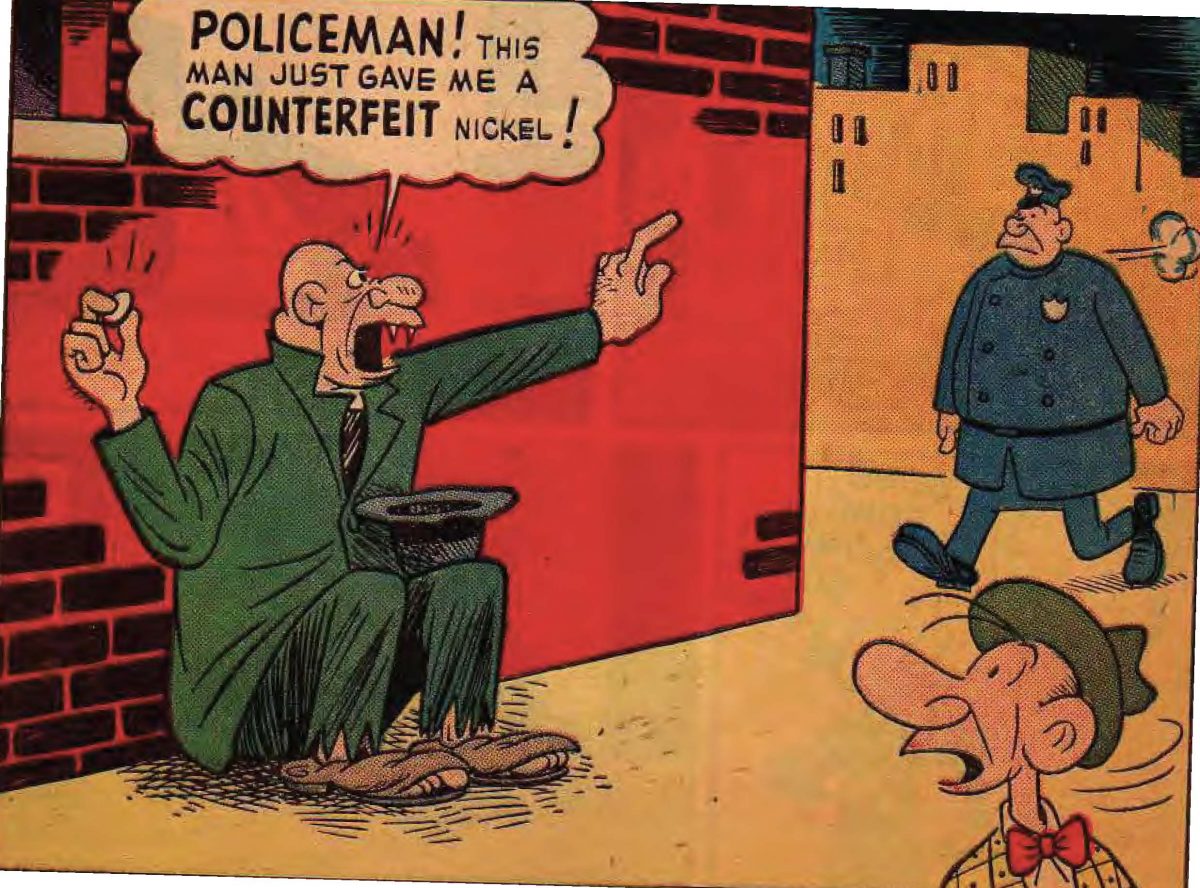

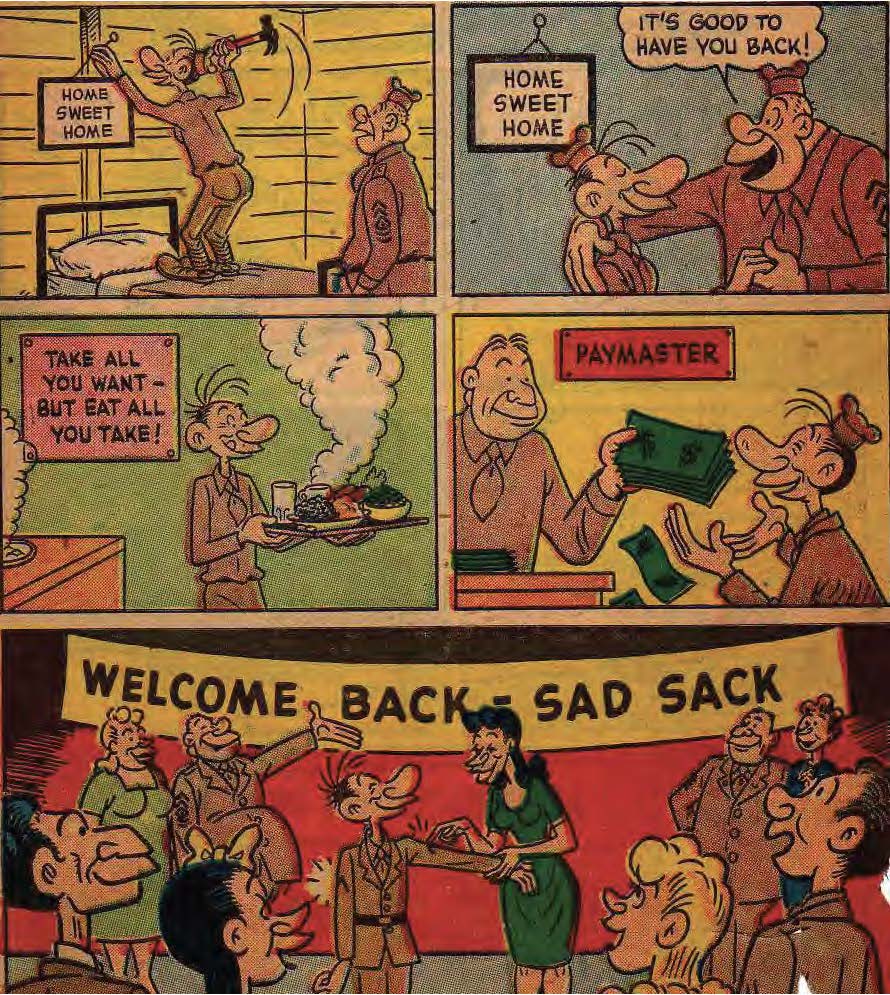

Because of Sad Sack’s appeal to teen and adult male audiences, and his particular resonance with soldiers, the U.S. Army contracted with Harvey Comics in 1951 to produce a promotional comic book to encourage reenlistment. This comic book, which was given to soldiers free of charge, poked fun at the Army while it also highlighted some of the challenges of readjusting to civilian life. The sixteen-page comic book, entitled “Sad Sack Goes Home,” opens with the usual litany of humiliations for Sad Sack before he is called to the captain’s office. Sad Sack is then overjoyed to learn that his time in the service has come to an end. Despite the lengthy presentation of benefits that accompany reenlistment, which are presented in detail throughout several panels, Sad Sack cannot wait to pick up his discharge papers and return to civilian life. His happiness, however, is short-lived. Sad Sack cannot find a clean and affordable place to live; his ex-girlfriend is now married with kids; clothes and food are shockingly expensive; and he finds himself trapped in a new job as a janitor. As the story ends, Sad Sack receives five cents in payment for his work – after all sorts of taxes, fees, commissions, and benefits are withdrawn – and that nickel turns out to be counterfeit. The story ends with Sad Sack reenlisting in the Army, enjoying an all-he-can-eat meal in the mess hall, getting a healthy paycheck, and celebrating his return with friends in the final panel.

This story, created by Harvey Comics staff in collaboration with the U.S. Army, epitomizes the appeal of Sad Sack to readers. Sad Sack is the same unlucky fellow who struggles with the day-to-day routine of Army life. And while the excitement of leaving the service is presented as genuine, the return to civilian life bedevils Sad Sack from the very start. On this score, the story offered a thinly veiled message about the challenges of readjusting to civilian life and the opportunities and benefits of being a soldier. The Army likely viewed the comic book as a valuable tool for retaining soldiers because Sad Sack was universally known to enlisted men, his experiences were widely relatable, and the benefits outlined in the story were clearly appealing in the face of the harsh realities of the world as presented to veterans.

Accordingly, the U.S. Army ordered 500,000 copies of “Sad Sack Goes Home” for use on military bases around the world. Although Baker was not involved in the creation of the story, he agreed to allow the Army to use the character without royalty or payment of any kind. Harvey collaborated with Army personnel on the project and printed the comic books as a public service. At a cost of $17,544, the Army acquired a half million comic books that promoted the opportunities offered to soldiers who reenlisted. To the officers who had organized the project, the book served as a low-cost, high-yield strategy for retaining soldiers who might otherwise have left the service for civilian life. The comic book, or “booklet,” as the Army termed it in its correspondence on the project, entered circulation in July 1951.

Only two months after it appeared, the Army’s Sad Sack comic book encountered criticism from an unusual source. In September 1951, Senator Homer Capehart (R-IN) attacked the comic after hearing about it from an angry constituent. Speaking to a reporter about the story, Capehart stated that the “alleged comic book” looked to him “like socialistic propaganda aimed at discrediting American industry.” Precisely at the same time that local groups were targeting comic books as pernicious influences on American youth, the senior Senator from Indiana asserted that these publications posed a danger to adults as well. Echoing concerns voiced by critics in cities and towns in his native Hoosier state, Capehart linked comic books to American anxieties exacerbated by the Cold War competition with the Soviet Union. According to Capehart, the Sad Sack comic book presented private businesses, the cornerstone of American capitalism, as cold, cynical, and exploitative.

Capehart’s public criticism of the Army’s Sad Sack comic book, widely covered in the American press, sealed its fate. The Army withdrew the comic from circulation immediately after Capehart’s remarks appeared in print. The comic book was removed from bases and no longer given to soldiers as a reenlistment tool. While internal Army correspondence stated that the “booklet was not receiving [the] desired response” at the time it disappeared from bases in September 1951, the timing was anything but coincidental. Now stuck with hundreds of thousands of comic books that had been denounced by a U.S. Senator, the Army decided to destroy the remaining copies. Less than two weeks after the controversy began, a public relations officer at Fort Ord in California reported that several hundred packages of the comic book were thrown into the incinerator on orders of the Sixth Army. While the Army was frustrated that newspaper coverage suggested that all 500,000 copies were destroyed – and that the entire cost to the taxpayer was wasted – it did not counter this narrative by announcing how many copies had actually been given out.

The Army’s burning of its own comic book, however, is not the end of the story. A month later on the floor of the United States Senate, Capehart spoke about the episode and inserted two documents – telegrams exchanged between George Baker and himself – into the official record. In his remarks in the chamber, Capehart reiterated his concern that the comic book “placed private employers in the worst possible light.” He also informed his fellow lawmakers that the Department of Defense had responded by destroying the remaining copies. Then, he shared the remarks of George Baker on the controversy, which focused on rehabilitating his reputation and that of his creation. Baker noted that he had not been personally involved in the project, but he had given it his blessing as a “patriotic gesture.” Furthermore, he emphasized that the Army had prepared the material with Harvey staff and that it had approved it for publication. In short, Baker argued, Capehart’s criticisms should be aimed at the Army, not himself or his character. Capehart’s response, also included in the Congressional Record, notes that Sad Sack is “one of his favorite comic book characters” and that he intended no criticism of the character. Then, presuming to speak for both of them, Capehart declared that what they object to “is the use of the powerful Sad Sack influence in such a way as to belittle American employers.” Capehart, again, condemned the comic book for its critique of American capitalism.

The controversy surrounding the Army’s Sad Sack comic book offers several valuable insights about comic book history and censorship. First, this episode highlights the influence of national politicians and the media in vilifying comic books. The destruction of hundreds of thousands of comic books resulted from the criticisms of a single U.S. Senator published in newspapers across the country. Second, the attack on Sad Sack illuminates popular anxieties about American society and culture that dominated popular discussions of comics in the early Cold War era. Although the specific concern in this instance is American business, the broader fears of comic books undermining American social and cultural values and institutions echoes the views of critics like Frederic Wertham. Finally, this affair raises the issue of censorship, although no one explicitly mentioned it at the time. Certainly, Senator Capehart did not see any problem with his critique or the outcome. Perhaps more surprising is the fact that George Baker did not mention it either in his response. However, if a U.S. Senator could believe that comic books posed such a threat to adult men in 1951 that the only solution was to incinerate them, it is not hard to imagine that his colleagues would be willing to take action against them to protect children a few years later. As comics readers today well know, these issues – an outspoken minority concerned about content, popular anxieties about social and cultural change, and censorship as a means of “protecting” audiences – are hardly confined to the distant past.

Article Links

Map of Comic Book Burnings in America, 1945–1955

Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency

R.C. Harvey, “George Baker and the Sad Sack,” December 20, 2013 (The Comics Journal)

“National Affairs: The Pressagent Touch,” October 1, 1951 (Time Magazine)

Extension of Remarks, Sen. Homer E. Capehart, Congressional Record Vol. 97, Appendix 15, pg. A6851

Brian M. Puaca is Professor of History at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, where he teaches a course on the history of comic books and American society. He can be reached at bpuaca@cnu.edu.