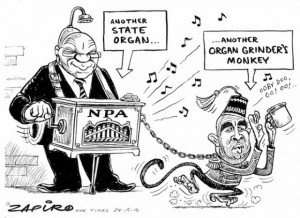

One of South Africa’s most well-known political cartoonists has become embroiled in controversy since the publication of a cartoon with what he said were unintended racist overtones. The cartoon by Zapiro, AKA Jonathan Shapiro, depicts the country’s top prosecutor Shaun Abrahams, a black man, as an organ grinder’s monkey.

One of South Africa’s most well-known political cartoonists has become embroiled in controversy since the publication of a cartoon with what he said were unintended racist overtones. The cartoon by Zapiro, AKA Jonathan Shapiro, depicts the country’s top prosecutor Shaun Abrahams, a black man, as an organ grinder’s monkey.

The cartoon published on May 24 was a commentary on South Africa’s long-running “spy tapes” scandal, which has taken down other government officials over the past ten years and implicates current president Jacob Zuma for taking bribes in exchange for a lucrative arms contract in 1999, when he was deputy president. Corruption charges against Zuma have been brought, dropped, and revived multiple times since 2005. Most recently, the nation’s High Court reversed a 2009 decision by Abrahams’ predecessor to drop the charges, but Abrahams then countered last week that he would appeal the court’s ruling and push for the charges to be dropped once again.

Abrahams’ decision was widely condemned by South Africans, who see it as yet more evidence of corruption and political cronyism since Abrahams was appointed by Zuma himself. But when Zapiro drew the president and prosecutor as an organ grinder and his dancing monkey, a debate spun off in the national press over the longtime association of simian imagery with racism. In response to criticism from political commentator Eusebius McKaiser, Zapiro initially published a column headlined “Why I Refuse to Self-Censor,” insisting that the cartoon must be considered in context. (As an aside, Zuma is always depicted in Zapiro’s cartoons with a shower head springing from his neck due to his testimony in a 2009 rape trial, where he said he avoided contracting HIV by taking a shower immediately after unprotected intercourse.)

By the next day, however, Zapiro seems to have reconsidered, describing the cartoon as “a mistake.” In an interview published May 27, he went even further, saying that “this is the first time ever that I am utterly sorry. I wish I could turn the clock back and I should never have done that.” For his part, McKaiser shot back in another column that “artistic criticism isn’t censorship,” explaining that while Zapiro certainly has the right to offend, he also should be prepared for sometimes impassioned responses to his work. McKaiser elaborated on the bargain that every artist makes with the public in a free society:

I still maintain that the balance of liberal democratic rights and values – which we signed up for in 1994 – demand that we accept that Zapiro can of course depict black people as monkeys if he so wishes. No one is asking him to be censored or asking him to censor himself. I certainly am not.

Instead of defending himself against the aesthetic and moral criticism levelled against this particular cartoon, Zapiro changes the subject by asserting speech rights.

That is lame. Speech rights are going nowhere. Too many of us value such rights to simply allow them to be trampled on.

But columnists, authors, artists, cartoonists, film-makers and anyone else in society who depicts their view of society and places that view in the public space is susceptible to criticism.

The same speech rights that entitle us to put our views in the public space demand of us to engage our interlocutors on the content of their criticism of our works.

Finally, McKaiser gladly accepted Zapiro’s previous challenge to a public debate. Although nothing has yet been scheduled, McKaiser added that he hoped the cartoonist would agree “to wear a monkey suit for the occasion. Just for laughs.”

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.