Welcome to Using Graphic Novels in Education, an ongoing feature from CBLDF that is designed to allay confusion around the content of banned books and to help parents and teachers raise readers. In this column, we will examine books that have been targeted by censors and provide teaching and discussion suggestions for the use of such books in classrooms.

Welcome to Using Graphic Novels in Education, an ongoing feature from CBLDF that is designed to allay confusion around the content of banned books and to help parents and teachers raise readers. In this column, we will examine books that have been targeted by censors and provide teaching and discussion suggestions for the use of such books in classrooms.

In our first column, we’ll take a closer look at Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi.

The autobiographical graphic memoir Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi was pulled from Chicago classrooms this past May by Chicago Public Schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett due to “inappropriate” graphic language and images, specifically, scenes of torture and rebellion. Parents, teachers, and First Amendment advocates protested the ban, and as a result — while still pulled from 7th grade — Persepolis is currently under review for use in grades 8-10. (For details, see CBLDF Rises to Defense of Persepolis.)

Persepolis is an important classroom tool for a number of reasons. First, it is a primary source detailing life in Iran during the Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War . Readers of all ages get a glimpse of what life is like under repressive regimes and relive this period in history from a different perspective. It also begs detailed discussion of the separation of church and state. Furthermore, this is a poignant coming-of-age story that all teens will be able to relate to and serves as a testament to the power of family, education, and sacrifice.

SUMMARY

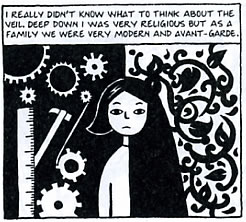

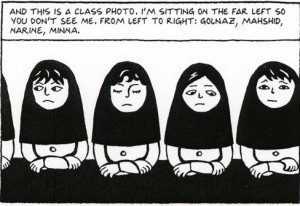

Persepolis is the story of Marjane Satrapi’s childhood and coming of age within a loving, educated family that lived in Tehran during the Islamic Revolution and Iran-Iraq War. It is drawn in simple, stark, black and white ink with style, poignancy, and elegant detail as well as occasional flourishes (usually in the dream sequences) traditionally found in Eastern art.

Introduction: Satrapi provides a brief text introduction that delivers historical context and background. She also explains her goal: to show that the West’s perception of modern Iran as an Islamic Fundamentalist country filled with “fanaticism and terrorism…is far from the truth…I also don’t want those Iranians who lost their lives in prisons defending freedom, who died in the war against Iraq, who suffered under various repressive regimes, or who were forced to leave their families and flee their homeland to be forgotten.”

Main Text: Satrapi depicts her childhood growing up in volatile Tehran between the ages of 6 and 14 ((1970-1984). It is a personal story, one we can all relate to as she talks about school, friends, and dreams, and yet her story is starkly different from ours as she grew up in Iran during war, religious upheaval, and revolution.

Main Text: Satrapi depicts her childhood growing up in volatile Tehran between the ages of 6 and 14 ((1970-1984). It is a personal story, one we can all relate to as she talks about school, friends, and dreams, and yet her story is starkly different from ours as she grew up in Iran during war, religious upheaval, and revolution.

Throughout Persepolis, Satrapi discusses the following:

- Tolerance and intolerance on personal, political, and social levels;

- Being required to do and say things she did not remotely believe in;

- The dramatic changes that took place in her school and personal life after the Revolution;

- The games she played growing up;

- Her various career goals, from “last prophet” to social rights advocate;

- Her father’s explanation of the history of the Revolution, from Reza Shah’s desire to overthrow the King of Persia to install a republic, to British aid to Reza Shah, to life under the Shah, to life after the Shah and the Revolution.

- The roles her family played in Iran, from being princes to revolutionaries and communists;

- The Iran-Iraq war and the role played by Islamic Fundamentalists, revolutionaries, common citizens, and the West;

- Her family’s search for truth;

- The totalitarian dictates of religion;

- The impact of class differences and status and how that changed pre and post Revolution;

- Typical coming of age issues such as rebelling against her parents, parties, music, and life ambitions.

TEACHING/DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS:

Culture and Cultural Diversity

Discuss the similarities and differences between growing up in an Islamic versus Western cultures in terms of:

Discuss the similarities and differences between growing up in an Islamic versus Western cultures in terms of:

- Going to school — classrooms, uniforms, curriculum

- Kids’ games and interests outside of School (Satrapi discusses how they played “Revolutionaries,” pretending to be Castro, Che Guevara, and Trotsky.)

- The difference in kids’ heroes between Islam and the West

- Career goals

- The place of religion in home, school, and government

- Adult, teen, and children’s involvement in the politics and issues around them

- Have students recall incidents in which Satrapi, as a child and later as an adult, had to do things because she was told to, without either understanding or believing in the rationale behind the edicts, which came from both her parents and the government. Discuss, re-enact, or have students create journal entries relaying what it feels like to be made to do things that you do not understand or want to do, and ask them to predict what the alternatives might have been.

- Discuss when one should forgive and forget, and when one should fight or at least stand up for their views and perspectives?

History, Governance, Civic Ideals, and Global Connections

- Define “revolution, “ and compare the Iran Revolution to the following:

- American Revolution

- French Revolution

- Communist Revolution

- Industrial Revolution.

- Compare Satrapi’s story of the Iran Revolution and Iran-Iraq War to those told by Western media and historians. Discuss the role of perspective.

- Discuss the roles of certain figures in revolutions.

- Ms. Satrapi discusses how she and her friends played “Revolutionary,” each child assuming a different role: Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Trotsky, and Lenin. Ask students why Satrapi and her friends picked these revolutionaries. Then, break the class into small groups to research these individuals.

- Ask students to come up with their own games of “Revolutionary.” Have them identify who they would play in the game and why.

On pages 12-13, Satrapi notes that to enlighten her, her parents bought books about Palestine, Castro, and revolutionaries, such as such F. Rezat, Dr. Fatemi, and H. Ashraf, of her country. Have students investigate the contribution Rezat, Fatemi, and Ashraf made to the Iranian Revolution.

On pages 12-13, Satrapi notes that to enlighten her, her parents bought books about Palestine, Castro, and revolutionaries, such as such F. Rezat, Dr. Fatemi, and H. Ashraf, of her country. Have students investigate the contribution Rezat, Fatemi, and Ashraf made to the Iranian Revolution.- Satrapi mentions her favorite book — a comic book entitled Dialectic Materialism, in which Descartes and Marx discuss “the material world.” Have students research and read the works of Descartes and Marx and then have them stage that discussion.

- Discuss truth and the nature of reporting news in Iran as well as in the West.

- On page 19, Satrapi relates a discussion she had with her father. After the revolution, textbooks were changed and while they were taught the new books in school, her father related the truth at home.

- On pages 83-84, 111, and 135, Satrapi mentions how they couldn’t trust the news reports and had to rely on other methods.

- Compare the role of religion in the West and in predominantly Islamic countries.

- Discuss the issues of church versus state and the religious debates that began in the West in the late 1700s to today.

Language, Literature, and Language Usage

Discuss the use of political slogans.

Discuss the use of political slogans.

- On page 115 Ms. Satrapi relays a slogan in Iran, “To die a martyr is to inject blood in the veins of society.” Ask students to discuss what this means and then have them compare this slogan to other political slogans from around the world.

- Discuss idioms on life, liberty, and/or revolution.

- On page 10 (see section below) Satrapi notes in simile that, “The revolution is like a bicycle. When the wheels don’t turn, it falls.” Discuss this image, and have students create their own idioms on life, liberty, and/or revolution.

- Have students go on a scavenger hunt for puns, similes, and metaphors throughout Persepolis.

- Have students hunt for Satrapi’s references to philosophers, political leaders and writers of Iran, Russia, and the West. Compare the difference in text types, use of language and text purpose when Satrapi discusses these figures versus when she tells her own story.

Modes of Storytelling and Visual Literacy

In graphic novels, images are used to relay messages with and without accompanying text, adding additional dimension to the story. Discuss with students how images can be used to relay complex messages. For example:

- On page 10, Satrapi notes that, “And so went the revolution in my country.” The image shows one large bicycle with seven seats and 20-30 people riding on it or lying on it, (taking up the whole bottom of the page) with arms, legs, and heads flailing in multiple directions. Have students analyze this image. Then, have students create text to replace the image. Discuss the pros and cons of relaying messages in text versus image.

- Page 77 contains text at the top: “Things got worse from one day to the next. In September 1980, my parents abruptly planed a vacation. I think they realized that soon such things would no longer be possible. …And so we went to Italy and Spain for three weeks…” The rest of the page has an image of buildings on either side, with swirls, a female figure rising from the swirls, and Marjane and her parents flying on a carpet above the woman and the swirls. Discuss the way text and images relay complex messages.

Suggested Prose Novel Pairings

For greater discussion on literary style and/or content here are some prose novels you may want to read with Persepolis:

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: A fictional accounting (based on fact) of life in Paris during the French Revolution.

- The Chosen by Chaim Potok: About a boy from an ultra orthodox Jewish family who wants to shape his own life and destiny and who wrestles with the role of religion in secular life.

- Marching for Freedom: Walk Together, Children and Don’t You Grow Weary by Elizabeth Partridge: An account of the Freedom March of 1965 that depicts the power of teen voices.

- Mao’s Last Dancer by Cunxin Li: An autobiography about Li’s rise from poverty in Communist China to dance stardom and a defection that caused an international incident. This account reflects life under a Communist rule, in which life choices are frequently dictated rather than chosen.

- The Kid’s Guide to Social Action by Barbara A. Lewis: Just as Marjane and her parents participated in demonstrations protesting aspects of Islamic rule, students can read how they might effect social changes in their communities.

- Snow Falling in Spring: Coming of Age During the Cultural Revolution in China by Moying Li (memoir): This work also reflects life under a Communist rule and how life choices are dictated under the regime.

- The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain by Peter Sis (memoir): This work reflects the lack of personal choice under Soviet Communist rule.

Common Core State Standards

This non-fiction memoir is full of advanced vocabulary, simile, metaphors, slogans, and details of historical events from a different viewpoint. It promotes critical thinking, relates a non-Western perspective of the turmoil in Iran during the Revolution and the subsequent Iran-Iraq War, provides verbal and visual story telling that addresses multi-modal teaching, and meets Common Core State Standards including:

- Key ideas and details : Citing textual evidence, determining a theme or central idea, describing how a plot unfolds, analyzing how particular elements of the story interact; analyzing how particular lines of dialogue or incidents of a text reveal aspects of a character or provoke a decision; analyzing a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature.

- Craft and structure : Determining the meaning of words and phrases including figurative and connotative meaning; analyzing how particular sentences, chapters, scenes or stanzas fit into the overall structure of a text; explaining how a point of view is developed; analyzing how a text’s structure or form contributes to its meaning; analyzing a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature; determining the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies; describing how a text presents information

- Integration of knowledge and ideas: Comparing and contrasting texts; and distinguishing among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text.

- Range of reading and level of text complexity: Reading and comprehending literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in grades 6-8; in grades 8-10 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

- Knowledge of language: Using knowledge of language and its conventions when writing, speaking, reading, or listening

- Vocabulary acquisition and use: Determining the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases; demonstrating understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in world meanings; and acquiring and using accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases.

- Research to build and present knowledge: Drawing evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research;

- Comprehension and collaboration: Engaging effectively in a range of collaborative discussions building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.

- Presentation of knowledge and ideas: Presenting claims and findings, sequencing ideas logically and using pertinent descriptions, facts, and details to accentuate main ideas or themes.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

- http://libwww.freelibrary.org/onebook/obop10/teacher_resources.cfm

- http://libwww.freelibrary.org/onebook/obop10/Persepolis_Discussion_Questions.pdf

- http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/

- http://www.pbs.org/wnet/wideangle/episodes/pilgrimage-to-karbala/memoir-marjane-satrapis-persepolis/marjane-satrapis-persepolis-introduction/1637/

- http://islamicunitstudies.wordpress.com/2009/06/17/persepolis-lesson-plans/

- http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/pictures-tell-story-improving-1102.html

Meryl Jaffe, PhD, teaches visual literacy and critical reading at Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth OnLine Division and is the author of Raising a Reader! and Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning. She used to encourage the “classics” to the exclusion comics, but with her kids’ intervention, Meryl has become an avid graphic novel fan. She now incorporates them in her work, believing that the educational process must reflect the imagination and intellectual flexibility it hopes to nurture. In this monthly feature, Meryl and CBLDF hope to empower educators and encourage an ongoing dialogue promoting kids’ right to read while utilizing the rich educational opportunities graphic novels have to offer. Please continue the dialogue with your own comments, teaching, reading, or discussion ideas at meryl.jaffe@cbldf.org and please visit Dr. Jaffe at http://www.departingthe text.blogspot.com.

All images (c) Marjane Satrapi.