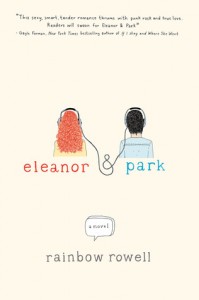

Rainbow Rowell, author of the best-selling young adult novel Eleanor & Park, spoke with CBLDF regarding the recent controversy she faced when two parents managed to gain the support of a Minnesota school district and library board to cancel planned speaking engagements due to her “dangerously obscene” book.

Eleanor & Park was released in early 2013, and the literary world fell in love. Not only was the novel an Amazon Best Book of the Month and a New York Times best seller, but it grabbed the attention of acclaimed author John Green (The Fault in Our Stars), who wrote in his heartfelt review of the book that “[he] had never seen anything quite like Eleanor & Park.”

Anoka Country Library also recognized how special the story is and selected Rowell’s novel for their summer reading program, inviting the author to speak at Minneapolis-area schools and libraries this fall. Unfortunately, those engagements were cancelled after the Anoka-Hennepin school district, county board, library board, and Parent’s Action League decided that the book was inappropriate. Not only did they rescind Rowell’s invitation to speak, but also demanded that Eleanor & Park be removed from the libraries and requested disciplinary action against the librarians who selected it.

And what, exactly, makes the book “dangerously obscene?” From a review on Parents Action League:

“…this book is littered with extreme profanity and age-inappropriate subject matter that should never be put into the hands and minds of minor children.”

Eleanor & Park follows the relationship of two misfit teenagers who fall in love over a series of comic book and mix-tape exchanges on a school bus. Park Sheridan is the only Asian kid in his neighborhood, and although he comes from a good family, he doesn’t fit in with anyone around him. He’s small, quiet, and slightly awkward, a little too feminine for his father’s taste. In fact, Park wonders why the heroines from the pages of comics do more for him than the girls he’s actually kissed — until he meets Eleanor. A spectacle among the other high school students, Eleanor stands out immediately with her unkempt red hair, androgynous gypsy wardrobe, and hardened exterior. Inside, though, Eleanor is painfully vulnerable about everything from her impoverished family to her body image — Eleanor is fat. Not an average sized girl with a couple of extra pounds, but a generous body like a “barmaid,” which is a desperately underrepresented type of beauty in young adult fiction. As she and Park begin a tentative friendship, both characters come alive with the realization that they finally fit with someone. The couple face bullies, domestic violence, exploration of racial identity, and understanding the class differences between their families in ways that feel authentic, heartbreaking, and relatable. Why should this book not be thrust into the hands of teenagers, especially those facing similar struggles?

Eleanor & Park follows the relationship of two misfit teenagers who fall in love over a series of comic book and mix-tape exchanges on a school bus. Park Sheridan is the only Asian kid in his neighborhood, and although he comes from a good family, he doesn’t fit in with anyone around him. He’s small, quiet, and slightly awkward, a little too feminine for his father’s taste. In fact, Park wonders why the heroines from the pages of comics do more for him than the girls he’s actually kissed — until he meets Eleanor. A spectacle among the other high school students, Eleanor stands out immediately with her unkempt red hair, androgynous gypsy wardrobe, and hardened exterior. Inside, though, Eleanor is painfully vulnerable about everything from her impoverished family to her body image — Eleanor is fat. Not an average sized girl with a couple of extra pounds, but a generous body like a “barmaid,” which is a desperately underrepresented type of beauty in young adult fiction. As she and Park begin a tentative friendship, both characters come alive with the realization that they finally fit with someone. The couple face bullies, domestic violence, exploration of racial identity, and understanding the class differences between their families in ways that feel authentic, heartbreaking, and relatable. Why should this book not be thrust into the hands of teenagers, especially those facing similar struggles?

Rainbow Rowell shares her thoughts on the banning, as well as why her story — and others like it — are important for young adults.

CBLDF: How did you first come to learn that the Parent’s Action League was making attempts to have Eleanor & Park removed from the library?

Rainbow Rowell: I heard in mid-August that two parents had objected to the book and gotten support from the PAL. But at that point, it seemed like it wouldn’t affect my trip. I didn’t really understand what was happening until the National Coalition Against Censorship got involved.

I read that the librarians who were recommending your book for their summer reading program could be facing discipline–do you know if they have?

The Parent’s Action League “alert” about Eleanor & Park asks that the librarians be disciplined. I’m not in contact with anyone inside the school district, but I don’t believe that this has happened.

This week, the teachers union came to the librarians’ defense, which I was really happy to see.

I was shocked when I read the specific reasons your book was being challenged — too much profanity and too much sexual content. I recall absolutely no graphic sex. It’s all implied. Did you and your publisher feel that the romantic content was appropriate for older teens? Had you received any push back until this event?

There’s no explicit sex or sexual scene in the book. The characters do kiss and touch each other, but not explicitly, and they eventually decide not to have sex. (Spoiler alert.)

The romantic content was never questioned — and has never come up with teachers and librarians. I don’t think it’s steamy, even for a YA book.

As a parent, I use Common Sense Media a lot to decide whether something is appropriate for my kids. And Common Sense gave Eleanor & Park a really great review, saying it was “a fabulous book for mothers (especially those who grew up in the ’80s!) to read along with their teen daughters.”

Common Sense Media recced it for people 14 and up, which I agree with.

When I first heard that the Parents’ Action League called the book “pornographic,” I thought, “Are we talking about the same book?”

I find the romance scenes really accurate in that way that only your first love can exist — you’re learning about yourself as a sexual person, you’ve finally found someone who doesn’t notice any of the flaws you do, and you’re dealing with an exceptional lack of privacy and free time to make these discoveries. What was important to you when you were writing the physical parts of their romance?

You know, through the whole book, through everything, I wanted the story to feel real. I tried to remember what it felt like to be 16, what it felt like to fall in love for the first time. What it felt like to be in that strange place between belonging to your parents and belonging to yourself.

You feel things so strongly at that age — and romance and sex are such potent and overwhelming concepts.

So I guess when I was writing those physical scenes, I was thinking about how awkward and new everything is. Not just the sex or the almost-sex — everything. By far the most explicit scene in the book is when Eleanor and Park hold hands for the first time. When I was writing their story, I didn’t want to skip past the handholding and the thrill of just sitting next to each other.

I feel like I should say that this was my approach to writing the whole story: make it feel real, remember everything as well as I could.

Eleanor & Park does have curse words in it, mostly used by a character that is mentally and physically abusive. Teenagers also occasionally use them. Eleanor is frequently offended by how much her stepfather curses, Park’s mother admonishes her family when they use inappropriate language, and Park himself tries to block out profanity on at least one occasion. Do you feel like anyone from the league actually read your book and looked at his or her concerns in context? And when dealing with material that could potentially be viewed as offensive, isn’t context key?

Right, right, right.

This is the thing that kept me up all night for two weeks. Like I just wanted to sit down with whoever put this report together and say, “YES, BUT IN CONTEXT…”

Because the very first line of the book is: “XTC was no good for drowning out the morons at the back of the bus. Park pressed his headphones into his ears.”

He’s trying to block out the cursing!

The two main characters of the book rarely curse, and when they do, they regret it. I don’t personally object to profanity — but in this book, the profanity separates Eleanor and Park from all the crude and cruel things happening around them. When Eleanor even thinks the F-word, she feels tainted by her terrible stepdad, who uses it all the time.

It was really healing/helpful for me when Linda Holmes wrote this piece about ugliness in Eleanor & Park for NPR. I felt like she said everything I’d been wanting to say about why banning this book is specifically cruel and absurd.

As an avid reader of YA, I’ve always found that the best YA books are ones that don’t tell their audiences how to behave in life scenarios they may face, but rather presents options and a platform for discussion. What responses have you received from teen readers on the impact your book has had on them?

Well, I hear from a lot of teenagers and adults. Young people are often really grateful that Eleanor isn’t described as perfect looking. (Neither of the main characters are.) They appreciate the idea that you don’t have to be extremely, conventionally beautiful to fall in love — or to be the main character of a love story.

Also, girls often talk to me about how kind and good Park is, which makes me so happy. I like to write about people who are trying to be good or to do the right thing. Park isn’t perfect, but he tries so hard. When a girl tells me she wants to find her Park, I always think, “YES. Find someone who will be kind to you. Someone who loves you for everything that you already are.”

Adults are more likely to talk to me about their own experiences with domestic abuse, bullying and poverty. I think those are issues that are easier to talk about after you have some emotional distance from them.

What are the risks of banning a book like Eleanor & Park?

Oh. I’m not sure I’m going to be able to put this eloquently.

I think that first of all, it undermines the work of educators and librarians who really care about their work and would never share a book with young people unless they really believed in it.

Also, my visit to the Anoka County public library was canceled. It’s so dangerous to keep ideas out of the public library just because you find them unpleasant or disagree with them. The freedom to read is the freedom to think.

As far as the risks to young readers — when I told my sister that people objected to the language in the book, her response was, “They should try living through it.”

I feel like, if you’re a kid like Eleanor who’s neglected and abused and bullied . . .

Or you’re a kid like Park, who feels isolated by his race and his inherent weirdness . . .

What does it say to you to have this book banned? I feel like it says that it’s not okay. To be a victim. To be a misfit. It’s not okay to talk about all the things that are hurting you, because your life is too ugly to mention.

All I want to say to those kids — and to Eleanor and Park — is, “You are okay. All the terrible things that happen to you don’t define you. You get to have beauty, too. You get to rise above.”

Currently, we are celebrating Banned Books Week and providing education, access, and platforms for books that have been challenged at some point. Have you ever had your access limited or restricted to certain pieces of literature?

Hmm. That’s a really interesting question. My mother was very strict about what we watched and listened to, but I think that’s very different. I wonder if my access was restricted and I didn’t even realize it?

I will say that the only thing my mom wasn’t strict about was reading; I think she thought that reading was an inherently healthy activity. And now I’m so glad! Books were my salvation as a teenager — they gave me hope when I couldn’t find it anywhere else

Even the prospect of reading gave me hope. Like, getting to read a book that I loved was enough to live for.

The National Coalition Against Censorship has been helping fight back for your book. Any updates on how it’s going? [CBLDF signed the letter sent in defense of the book and Rowell’s talks. —Ed.]

Yes, the coalition just formally protested the county’s decision to cancel my visits. (It’s confusing because the challenge against my book involved the school district, the county board and the public library board.)

The goal is to support the school and public library in keeping the book on their shelves — and for me to still visit the area and talk to students who read it.

Your talks that were planned in the school district and libraries were cancelled. What were you planning on discussing? What are parents, teachers, and young people missing out on when they deny you — and any other authors — time with their communities?

Oh, I was hoping to talk about Eleanor & Park. I would have talked about why I wrote it and answered any questions the students had about it — or about writing. I just got back from a school in Baltimore where my book had been a summer reading pick. It was amazing. Like a giant book club. For me, it’s exhilarating and fascinating to see the characters through other people’s eyes. And I think, for the students, it’s cool to be able to ask the author why certain things happened or didn’t happen. Whenever I go to a school, we talk a lot about the book’s ending. And also about Eleanor and Park’s families. I end up telling the students all the things I know about the characters that I didn’t put in the book.

CBLDF is a sponsor of Banned Books Week. Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Casey Gilly is a comics journalist and cat enthusiast living in Oakland, CA, where she eats tacos and plays ukulele.