It may come as a surprise, but the freedom of speech laid out by the First Amendment doesn’t actually include all forms of speech. Roth v. United States is a landmark case that held that obscene speech was a category that did not fall under the umbrella of First Amendment protection. This case also clumsily tried to define what obscenity actually is, which led to much debate until the Miller Test was established in Miller v. California almost 16 years later.

Roth v. United States is actually a combination of two lower court cases that had similar legal facts and issues. The goal of this case was to test the constitutionality of both federal and state laws that banned obscene speech.

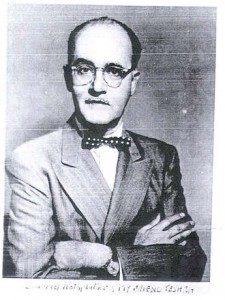

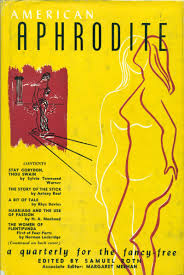

Samuel Roth, born in 1893, immigrated from Eastern Europe to Manhattan at the age of 4. In the Land of Opportunity, he began working at extremely young age of 8 years old. Roth continued to work small jobs to help earn money for his family until the age of 16, when he discovered his love for writing while working for the New York Globe as a correspondent. Shortly after, he lost this job and became homeless but continued his dreams of being a writer despite the hardship. This perseverance gave him the opportunity to attend Columbia University for a year on scholarship, and eventually he opened his own bookstore and started his first magazine. Unfortunately, as things were finally starting to look up for Roth, he was utterly destroyed by the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression. The desperate circumstances led Roth to the distribution of erotic literature as a means to earn some sort of income. Despite numerous fines and prison sentences due to his new career path, he continued this activity  until 1957, when he promoted a publication called American Aphrodite using circulars and advertisements. Roth was charged and convicted under a federal obscenity statute for mailing the circulars, which were deemed obscene because they advertised a publication that contained literary erotica and nude photographs.

until 1957, when he promoted a publication called American Aphrodite using circulars and advertisements. Roth was charged and convicted under a federal obscenity statute for mailing the circulars, which were deemed obscene because they advertised a publication that contained literary erotica and nude photographs.

In California, David Alberts ran a mail order business and was charged and convicted under the California Penal Code, which made it illegal to “keep for sale obscene and indecent books” and to promote such material.

Before these two cases, it had yet to be determined if it was even constitutional to have laws that suppressed people’s freedom of speech based on content that was considered obscene or lewd. So, in 1957, Alberts’ and Roth’s cases were combined in order for the Supreme Court to finally tackle this issue.

In their decision, the Court starts out by looking at the history of the freedom of speech. It makes it clear that the First Amendment doesn’t give absolute protection, but it is not necessarily clear on what exactly is not protected. Right off the bat, when the Constitution was being ratified, the majority of states instituted laws against libel, blasphemy, and profanity. The purpose of the First Amendment is to promote the free exchange of ideas about political and social change, yet it is not necessary for some things to be protected. Justice Brennan clarifies this further:

All ideas having even the slightest redeeming social importance — unorthodox ideas, controversial ideas, even ideas hateful to the prevailing climate of opinion — have the full protection of the guaranties, unless excludable because they encroach upon the limited area of more important interests. But implicit in the history of the First Amendment is the rejection of obscenity as utterly without redeeming social importance”

If obscene speech is utterly without redeeming social importance, then there is no need to protect it because it does not promote the goals of the First Amendment. Now that the court determined that obscenity should be categorically excluded, it is important to actually articulate what the court sees as obscene rather than just pointing to the Webster’s dictionary definition of the word. Justice Brennan makes it clear that sex itself is not to be considered obscene — it is far too integral to life to not be able to discussed or depicted in a protected manner — so something more would be needed to define obscene material. The court defined the “something more” as prurience, or the arousal of or appeal to sexual desire:

Obscene material is material which deals with sex in a manner appealing to prurient interest. The portrayal of sex, e. g., in art, literature and scientific works, is not itself sufficient reason to deny material the constitutional protection of freedom of speech and press….It is therefore vital that the standards for judging obscenity safeguard the protection of freedom of speech and press for material which does not treat sex in a manner appealing to prurient interest.

In 1957, the only other legal standard to define obscenity was found in the 1868 British case, Regina v. Hicklin. This standard was previously followed by some U.S. courts, but the Supreme Court decided that it was not going to work. The Hicklin test for obscenity looked at isolated passages, judged by the most sensitive people. This test just couldn’t work — surely anyone could claim that even the most innocuous statement could appeal to the prurient interest, and the court would have to stand by such claims. The Hicklin test was frequently used against legitimate works of literary and visual art, and it effectively gave control of freedom of speech to parties that were very religious or conservative. The Court articulated a better standard for defining obscenity:

The test in each case is the effect of the book, picture or publication considered as a whole, not upon any particular class, but upon all those whom it is likely to reach. In other words, you determine its impact upon the average person in the community. The books, pictures and circulars must be judged as a whole, in their entire context, and you are not to consider detached or separate portions in reaching a conclusion. You judge the circulars, pictures and publications which have been put in evidence by present-day standards of the community. You may ask yourselves does it offend the common conscience of the community by present-day standards.”

The new standard required looking at the questionable speech in comparison to the work as a whole. The Court recognized that things taken out of context can acquire a completely different meaning than is intended, so the work must be viewed in its entirety in order to fairly judge the material. Also, the material is to be judged based on community standards and not on the opinions of individuals, who might be unreasonably intolerant. Therefore, if a very liberal community wished to grant a work freedom of speech, it would not be hindered by the opinion of one overly conservative individual and vice versa.

In Roth v. United States, the Court didn’t just conclude that obscenity falls outside of First Amendment protection and that a stronger standard for defining obscenity was needed. The Court also concluded that Roth and Alberts’ convictions were proper under the Court’s new definition of obscenity. Roth subsequently served a 4-year prison term. The decision has since been overturned, but this 1957 case is a landmark because it begins the long road toward defining an important facet of First Amendment protection.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Eric Margolis is a 3L at St. John’s Law School who wishes to pursue a career in Entertainment / Intellectual Property law.