One of our missions here at CBLDF is promoting the use of comics and graphic novels in schools — hence our publications Raising a Reader! How Comic & Graphic Novels Can Help Your Kids Love to Read! and CBLDF Presents Manga: Introduction, Challenges, and Best Practices, as well as Meryl Jaffe’s column Using Graphic Novels in Education. So, we were thrilled to see the Washington Post’s comics blogger Michael Cavna recently feature 10 graphic novels from 2013 that should be embraced by educators to “smartly employ the resources of visual learning.”

One of our missions here at CBLDF is promoting the use of comics and graphic novels in schools — hence our publications Raising a Reader! How Comic & Graphic Novels Can Help Your Kids Love to Read! and CBLDF Presents Manga: Introduction, Challenges, and Best Practices, as well as Meryl Jaffe’s column Using Graphic Novels in Education. So, we were thrilled to see the Washington Post’s comics blogger Michael Cavna recently feature 10 graphic novels from 2013 that should be embraced by educators to “smartly employ the resources of visual learning.”

Cavna’s essay is inspired by the experience of a young relative, whose grade school teacher forbade her from doing a book report on David Hall’s Stitches — or even reading it in the classroom — because “Graphic. Novels. Aren’t. Books.” Although he notes that this attitude is increasingly rare, Cavna argues that more graphic novels deserve to be not simply tolerated as leisure reading, but incorporated into the curriculum. After all, he says:

Why not use every effective teaching tool at our disposal? Decades of studies have shown the power of visual learning as an effective scholastic technique. Author Neil Gaiman…recently noted that comics were once falsely accused of fostering illiteracy. We now know that comics — the marriage of word and picture in a dynamic relationship that fires synapses across the brain — can be a bridge to literacy and a path to learning.

Cavna’s chosen 10 include:

-

March by John Lewis: Partly inspired by Congressman and Civil Rights hero Lewis’ experience of reading the comic Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story in his youth. March was co-written by Andrew Aydin, a former aide and comics fan who found a kindred spirit in Lewis. Cavna calls the book “a landmark that belongs in every school library and every classroom.”

-

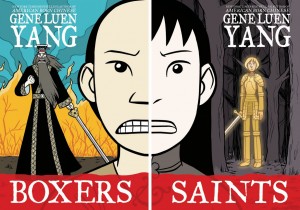

Boxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang: Says Cavna, “before Yang was a two-time finalist for the National Book Award, he was a high-school teacher who observed up close how some students respond better to visual learning.” In fact, we’ve featured this two-volume work in a Using Graphic Novels in Education post, which you can read here!

-

The Freddie Stories by Lynda Barry: A humorous but nuanced exploration of teenage anxieties — “measured against the actual adolescence of many kids, enjoying a little schadenfreude at Freddie’s fictional expense is positively a laff riot.”

-

Hip-Hop Family Tree by Ed Piskor: A detailed and reverent account of the 1970s origins of hip hop which “satisfies a distinct need in classrooms and libraries: Literate comics that reflect a facet of life many students actually care about.”

-

The Great War by Joe Sacco: A 24-foot-long wordless accordion-style foldout illustrating a single day in World War I. Cavna says: “So much about size and scope and tragic enormity can be lost in the translation when a student is perusing a textbook or half-sleeping through an in-class film.”

-

The Property by Rutu Modan: A young Jewish woman accompanies her grandmother to Poland as they try to recover the family property that was lost in World War II; Cavna calls it “an accessible and unintimidating way for teen students to approach the larger fallout of war.”

-

Marble Season by Gilbert Hernandez: An all-ages-appropriate account of 1960s childhood that “could convert many next-generation children into comics readers…[w]hile the kiddoes are still impressionably young.”

-

Battling Boy by Paul Pope: Cavna says the action-packed teen superhero story is “the sort of book that could turn a reluctant reader into an aspiring wordmaster.”

-

Woman Rebel by Peter Bagge: A biography of birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger that uncovers “over-the-top escapades from a person who curated a somber image for politics’ sake.”

-

Zits: Chillax by Jerry Scott: An “illustrated novel” from the creators of the newspaper comic. Cavna notes that the genre pioneered by Diary of a Wimpy Kid creator Jeff Kinney has “helped engage a new generation of young readers — largely those pre-teen grade-schoolers who will read healthy swaths of text if broken up even only occasionally by deceptively simple art and hand lettering, which function as winking visual cues of a non-threatening aesthetic.” Sherman Alexie’s frequently-challenged Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian also fits in this category.

With so many curriculum-worthy graphic novels in just one year, Cavna expresses hope that “the persistent empty prejudices against such works will fall.” Obviously, he says, the challenge the graphic literature must overcome in schools is “not one of providing quality stories, but of recasting public perception of the illustrated medium — and educators stand smack on the front lines of shifting perspective.” Stay tuned to CBLDF for more resources to aid in that transformation!

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read in 2014! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.