Welcome to Using Graphic Novels in Education, an ongoing feature from CBLDF that is designed to allay confusion around the content of graphic novels and to help parents and teachers raise readers. In this column, we examine graphic novels, including those that have been targeted by censors, and provide teaching and discussion suggestions for the use of such books in classrooms.

“Today, although as a whole, the industry is still male-dominated, more women are drawing comics than ever before, and there are more venues for them to see their work in print. In the 1950s, when the comic industry hit an all-time low, there was no place for women to go. Today, because of graphic novels, there’s no place for aspiring women cartoonists to go but forward.” — Trina Robbins, Pretty in Ink (2013)

In this post, to close out Women’s History Month, we look at two very different books with two very different approaches to celebrating women’s contributions.

Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists 1896-2013, by Trina Robbins, is a more traditional biography that discusses the lives, times, struggles, and contributions of women in the world of cartoons and comics. (Recommend for high school and older.)

Bad Girls: Sirens, Jezebels, Murderesses, Thieves and Other Female Villains, by Jane Yolen and Heidi Stemple, illustrated by Rebecca Guay, incorporates both prose and illustration to put the deeds of 26 women — who were both famous and infamous — in perspective. (Recommended for middle school readers.)

Let’s take a closer look.

Table of Contents

- OVERVIEW

- TEACHING/DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS

- SUGGESTED PAIRED READINGS

- COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS(CCSS)

- ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

OVERVIEW

Pretty in Ink by Trina Robbins

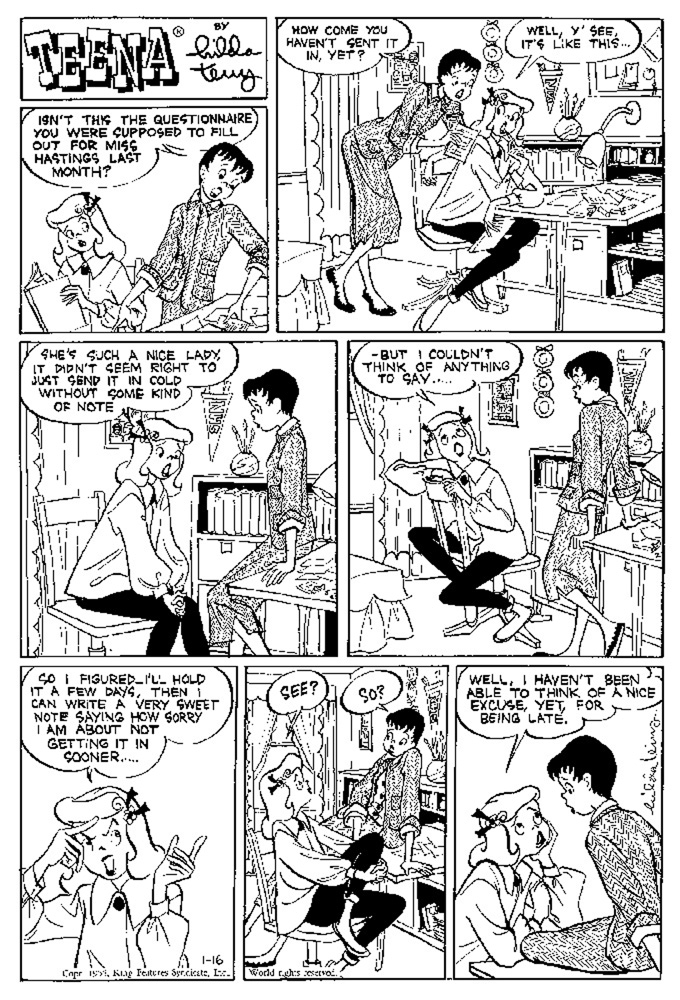

By cartoonist and comic historian Trina Robbins, Pretty in Ink explores 117 years of female cartoon creators and artists. Not only does Robbins discuss the lives of these women, but she puts them and their contributions in the context of their times. Pretty in Ink is a history of women cartoonists and of the cartoon and comics industry as a whole. Robbins has researched and relayed the stories behind the women in comics and cartoons, along with some outstanding samples of their work.

Pretty in Ink relates the role of women in the history of comics in eight chapters:

- The Queens of Cute

- The Pursuit of Flappiness

- Depression Babies and Babes

- Blonde Bombers and Girl Commandos

- Back to the Kitchen

- Chicks and Womyn

- See You in the Funny Pages

- Postscript: 21st Century Foxes

Chapter 1: The Queens of Cute is devoted to the first women creators or artists of comics. For the most part, women from 1895 to the 1920s created comics with cute cherubic kids who got into trouble (i.e. Kewpies, and The Turtle Tales of Kaptin Kiddo) or they were creating/writing about suffrage and love (i.e., Flora Flirt). To help make ends meet, many of these women were also drawing for corporate advertising for companies such as Campbell (i.e. the Campbell Soup Kids, Jello, and Ivory Soap).

Chapter 2: The Pursuit of Flappiness takes us from 1920s flappers to the Great Depression. These were the days and times of pretty girls and flappers. Nell Brinkley set the style and stage during the 1920s with her “Brinkley Girls,” whose fashionable clothes and flamboyant hair inspired controversy and fan mail. (Robbins notes that Florenz Ziegfeld made his fortune glorifying Brinkley Girls in his Ziegfeld Follies.) Robbins notes that while Brinkley created the what many considered the ultimate female, her daily panels provided sharp commentary of women’s roles and rights of her time, “squeezing” in important comments on suffrage, working women, and women in sports. Brinkley is just the starting point in the chapter –Robbins then discusses the other women contributors of this era and their valuable contributions to comics.

Chapter 3: Depression Babies and Babes takes us from roaring parties to depression. Robbins notes that while the average heroine of the 1920s had been a pretty girl, often a co-ed with nothing on her mind but boys, the 1930s plunged America into a the Great Depression and brought us “the Depression strip” (i.e. Apple Mary by Martha Orr). Robbins notes:

“This type of strip featured unglamorous protagonists dealing with real problems: poor but happy American households; upbeat unflappable orphans; plucky working girls (i.e. Brenda Starr by Dale Messick) out to earn a living rather than merely having a good time.” (p. 51)

Chapter 4: Blonde Bombers and Girl Commandos reflects America in 1940s — a country teetering on the brink of (and then collapsing into) war. Robbins notes that movies, pulp fiction, and the new medium of comic books all echoed the action-oriented themes of war. While earlier comics had been about cute animals and kids and pretty girls out to have fun in a carefree world, women were now more involved men’s world — both in the story content and in their production. Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr, for example, paved the way with a Rita Hayworth-like reporter who parachuted from planes, joined girl gangs, escaped from kidnappers, almost froze to death in snow-covered slopes, and got marooned on desert islands. Other comics followed with female spies, female commandos and undercover agents soon followed.

Robbins notes, however, that while other comics had women as foils for the hero to rescue, only the Fiction House comics had women in charge. Fiction House, started in 1936 by Jerry Iger and Will Eisner, was also the company that hired more women cartoonists than any other. It was also one of the only publishers who had women writing the stories.

As America entered the war, women assumed men’s places at work as the men went off to fight. Robbins notes that while few women drew the costumed heroes that had been popular since Superman in 1938, most excelled at and drew female figures. Typical wartime heroine titles were Yankee Girl (drawn by Ann Brewster) and Blonde Bomber and Girl Commandos (drawn by Jill Eglin and later Barbara Hall). Furthermore, women were able to work under their own names. The only times pseudonyms were used was when drawing and / or creating action strips. Those remained male domains.

Chapter 5: Back to the Kitchen relates what happened to women and the industry after the war. The returning men assumed the production of the superhero / action comics, while the women developed children’s action comics, teen comics, and love comics. Robbins notes that teen and romance comics continued to employ women throughout the 1950s, but the number of women in the field slowly dropped, with many female artists moving into illustrating children’s books. Robbins pegs the recession in the comics market during the 1950s to Dr. Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent , which (falsely) claimed that comics were responsible for juvenile delinquency. DC and Marvel, the two major comic book publishers to survive the resulting comic book depression began gearing themselves toward superheroes and the young male market. Female-oriented comic books were being slowly phased out.

Chapter 6: “Chicks and Womyn relates what the female comic book artists and creators did to survive the post-Wertham era. They, like most of the comic book industry, went underground, developing the comix market. Robbins notes that the early comix were psychedelic, focusing on design rather than story. The women’s underground comics of the later 1970s dealt with political and social issues from the female perspective.

By the 1970s, the only way for women to produce comic books was on their own, and so many women, including Robbins, created their own anthologies. The late 1970s saw the beginning of a boom in self-publishing and in small press black-and-white comics. It also saw the rising of comic book specialty stores.

Chapter 7: See You in the Funny Pages relates how in the 1980s and 1990s, attempts at producing comics for women and girls were scattered and mostly failed because comic book stores either didn’t carry them or ordered too few and failed to reorder when their few copies sold out. These comic book stores traditionally catered to the young male market that the major comic book publishers courted. In 1993, Robbins notes that Friends of Lulu — a group of the comic book industry’s women began to create and distribute their own comics with mixed success. Women creating comic strips, however, met with more success, as many were self-syndicated.

Chapter 8: 21st Century Foxes relays the successes and disappointments of the 21st Century (to date). In terms of the disappointments, Robbins notes that women creators, artists, and inkers are still significantly underrepresented in the major publishing houses. She notes, for example that in 2011, as DC opened their new line of comics, “The New 52,” only 1% of the new line creators were women, and 12% of their canceled strips were done by women.

On the positive side, with Will Eisner’s A Contract with God and Art Spiegelman’s 1992 Pulitzer Prize winning Maus, the graphic novel became a more accepted art and literary form. Now there are more than simply superhero graphic novels available — there are graphic stories (fiction and nonfiction) and graphic memoirs, with more and more women behind the pen. Webcomics, which are mostly creator owned, have also give women a stronger voice in the industry. It is on this upbeat note that Robbins ends her history with the hope of even greater access to women’s stories and women’s work in the future.

Bad Girls: Sirens, Jezebels, Murderesses, Thieves and Other Female Villains

By mother-daughter team Jane Yolen and Heidi Stemple and illustrated by Rebecca Guay, this book explores notorious women throughout history while trying to add perspective on why these women were both famous and infamous.

Their key message is a thoughtful one:

“There are more bad girls in history than we can count… Often, though, a tough girl, an outspoken girl — is mistaken for a bad one… In this book we’re…looking at the baddest of the bad, as well as those who may have been just misunderstood…Every crime — no matter how heinous — comes with its own set of circumstances, aggravating and mitigating, which can tip the scales of guilt. And views change. The line between right and wrong, criminal and hero, good girl and bad, is sometimes very thin.” (Pp.1-2)

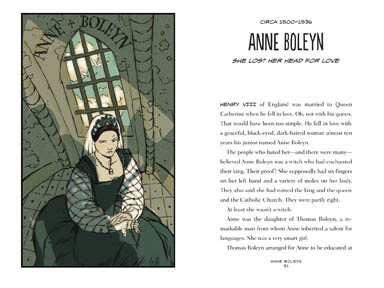

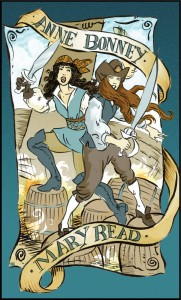

In this 146-page, predominantly text-based book, Yolen and Stemple present a 2- to 5-page (prose) biographical sketch for 26 notoriously “evil” women from biblical times to the present. Following each sketch is a one-page comic in which mother and daughter discuss the woman. While the biographical sketches provide information on these murderesses, pirates, bank-robbers, queens, spies, and all-around badass women, the comic component adds sass as the creators attempt to provide perspective by debating the actions of the women portrayed.

Guay provides a stunning visual portrait of each the characters and engaging graphic art for the comics, and Guay’s portraits are outstanding. They bring each woman to life while adding an air of mystery, reinforcing the authors’ wish to empower the reader to come to their own conclusions about each of the women depicted. While the comic strip and discussion between mother and daughter becomes somewhat repetitive and predictable, the historical perspective they provide (in chronological order) contains intriguing facts and speculations with just enough information to whet the appetite The book provides additional resources in the bibliography for full school reports and discussion.

The 26 femme-fatales featured in the book on are: Delilah, Jezebel, Cleopatra, Salome, Anne Boleyn, Bloody Mary, Elisabeth Bather, Moll Cutpurse, Tituba, Anne Bonney and Mary Read, Peggy Shippen Arnold, Catherine the Great, Rose O’Neal Greenhow, Belle Starr, Calamity Jane, Lizzie Borden, Madame Alexe Popova, Pearl Hart, Typhoid Mary, Mata Hari, Ma Barker, Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner, Bonnie Parker, and Virginia Hall.

TEACHING/DISCUSSION SUGGESTIONS

Cultural Diversity, Civic Responsibilities, and Social Issues

Pretty in Ink

- Use this book as a reference to a particular period of American history from 1896 to the present. Look at the comics Robbins selects and analyze and discuss how the reflect the period in which they were written.

- Select a period of American history (1896-present), and compare, analyze, and discuss women’s roles in comics versus other industries at that particular time.

- Use this book to discuss the course of American publishing. How has it changed? Ask students to predict where it is going.

- Challenge students to explore the work of one female creator in particular. Ask them to examine how she entered the industry, the work for which she was famous, and the challenges she faced in her career.

Bad Girls

- Discuss how history and changing historical perspectives change how people see figures such as the women featured in Bad Girls. Consider whether the women are perceived differently now than they were when they lived and what might have produced that difference in perspective.

- As the authors present twenty-six portraits, they are, by necessity, somewhat oversimplified. Select one of these women and learn more about them and to create a mock trial for their “crimes.”

Language, Literature, and Language Usage

Pretty in Ink

- Select comics done by men versus comics done by women of a particular tie period. How do they differ in content, in style, and in language?

- Reading through Pretty in Ink one gets a very definite perspective on history. Discuss this perspective and how it influences one’s understanding of the eras involved. Are there other perspectives in the book?

Bad Girls

- Compare the language used in the prose with the language used in the comic strips that appear throughout the book. How do the tones differ? How are they similar?

- Make a table comparing the words and images used to describe the actions of one (or several) of the women in the book. Differentiate between words and images that are considered negative and those considered positive. Does the book determine whether the woman is bad or is it left to the reader to decide? How is this accomplished?

Critical Thinking and Inferences

Pretty in Ink

- Investigate the Great Depression and World War II and how they affected the roles of women in American society. Based on what is learned, predict how the role of women in comics might be different if either event had not happened.

- Compare the topics covered by women early in the comics era with those covered by women starting in the 1970s. How did they change, and what were some of the external factors (societal changes, changing roles in the home and workplace, etc.) that might have driven these changes?

Bad Girls

- Examine why some women are considered “bad” and why some women are considered “good.” What are the characteristics of each type of woman?

- Are the women depicted in Bad Girls actually bad? Discuss why or why not.

- While Bad Girls presents notoriously evil women, have students research and evaluate women who, fall into the category of “a tough girl, an outspoken girl … mistaken for a bad one” — women who made enemies, whom many would have said were “bad” but others would have said were “good.” Some examples:

- Isabella of Castile (Queen Isabella)

- Elizabeth I, Queen of England

- Empress Dowager Cixi of China

- Maria Theresa (enlightened despot); Hannah Szenes (poet, spy, resistance fighter)

- Eva Peron

- Emmelie Pankhurst (militant suffragette)

Modes of Storytelling and Visual Literacy

In graphic novels, images are used to relay messages with and without accompanying text, adding additional dimension to the story. Compare, contrast, and discuss with students how images can be used to relay complex messages. For example:

Pretty in Ink

- While Pretty in Ink is more of a traditional history and relies on prose to carry the narrative, it is heavily illustrated, reproducing many pieces by female comics creators and cartoonists. Pick two images, one from the beginning of the book and one from later on, and compare the two based on style, use of color, and content.

- Ask students to draw their own comic strip or comic book depicting the life of one of the female cartoonists profiled in Pretty in Ink. Then, discuss how comics can be used to connect with biographical subjects.

Bad Girls

- Compare and contrast the art styles and designs Guay uses for these women. Also compare the art and design of the Guay’s portrayal of the women versus Yolen and Semple’s discussions.

- Bad Girls is an excellent example of a creative hybrid book incorporating both prose and comic formats. Evaluate and discuss how Yolen, Stemple and Guay have managed to do this, and how effectively they’ve accomplished their goals.

SUGGESTED PAIRED READINGS

Pretty in Ink

- The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, by David Hadju: Examines how Fredric Wertham’s attack on comic books changed the industry forever.

- Persepolis by Maryanne Satrapi: An autobiographical graphic novel that explores the artist’s upbringing in Iran during the 1979 Revolution.

- Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, by Gerald Jones: Examines the colorful characters that populated the comic book industry during its advent.

- Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, by Scott McCloud: Using the comics format, this graphic novel illustrates how comics are read, how they are made, and how they are used to tell stories.

- Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist, by Nancy Goldstein: Examines the life of Jackie Ormes, one of the few African American female cartoonists, who drew comics in the 1930s to the 1950s.

- Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics, by Hilary L. Chute: Explores the work of several contemporary female comics creators.

Bad Girls

- Goose bottom Books The Thinking Girl’s Treasury of Dastardly Dames: An outstanding collection of books, each book devoted to a dastardly dame such as:

- Cleopatra: Serpent of the Nile

- Agrippina: Atrocious and Ferocious

- Mary Tudor: Bloody Mary

- Catherine de Medici: The Black Queen

- Njinga: The Warrior Queen

- Marie Antoinette: Madam Deficit

- Cixi: The Dragon Empress

- Lily Renée, Escape Artist: From Holocaust Survivor to Comic Book Pioneer, by Trina Robbins and Illustrated by Margaret Oh and Anne Timmons: Shares the story of Holocaust survivor and comics pioneer Lily Renée Wilheim, who wrote comics such as The Werewolf Hunter, Senorita Rios, and more.

- Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas, by Jim Ottaviani and illustrated by Maris Wicks: Uses the graphic novel format to examine the lives of three of the most prominent female primatologists.

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS(CCSS)

Both Pretty in Ink and Bad Girls are nonfiction biographical works. Pretty in Ink takes a much more traditional approach that relies on prose but incorporates copious illustrations of the comics and cartooning work of women over the last 100-plus years. Bad Girls incorporates comics as a way to offer another perspective on some of history’s most notorious women. Both rely in varying degrees on verbal and visual storytelling that addresses multi-modal teaching, and meets Common Core State Standards.

Pretty in Ink, given its reliance on higher-level prose and coverage of some of the more mature comics created by women, is recommended for high school level and higher. Bad Girls is recommended for middle school, but it may find traction in higher-level classes (or with reluctant readers) as a jumping-off point for more in-depth coverage of historical women and how perceptions of these figures has shifted over time.

The books meet the following Common Core Anchor Standards:

- Knowledge of Language: Apply knowledge of language to understand how language functions in different contexts, to make effective choices for meaning or style, to comprehend more fully when reading or listening.

- Vocabulary Acquisition and Use: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases by using context clues, analyzing meaningful word parts, and consulting general and specialized reference materials; demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meaning; acquire and use accurately a range of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases sufficient for reading, writing, speaking and listening at the college and career readiness level.

- Key ideas and details: Reading closely to determine what the texts says explicitly and making logical inferences from it; citing specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text; determining central ideas or themes and analyzing their development; summarizing the key supporting details and ideas; analyzing how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of the text.

- Craft and structure: Interpreting words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings and analyzing how specific word choices shape meaning or tone; analyzing the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs and larger portions of the text relate to each other and the whole; Assessing how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

- Integration of knowledge and ideas: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually…as well as in words; delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence; analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take

- Range of reading and level of text complexity: Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently

- Research to Build and Present Knowledge: Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based of focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation; gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of teach source, and integrate the information while avoiding plagiarism; draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- Comprehension and collaboration: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively; integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively and orally; evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

- Presentation of knowledge and ideas: Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization; adapt speech to a variety of contexts and communicative tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate.

These books and related discussions also cover the following themes identified by The National Council for the Social Studies:

- Culture and Cultural Diversity: “…students need to comprehend multiple perspectives … to consider the strengths and advantages that this diversity offers to the society in general and to their own growth…to analyze the ways that a people’s cultural ideas and actions influence its members…”

- Time, Continuity, and Change: “…facilitate the understanding and appreciation of differences in historical perspectives and the recognition that interpretations are influenced by individual experiences, societal values, and cultural traditions… examine the relationship of the past to the present and extrapolating into the future… provide learners with opportunities to investigate, interpret, and analyze multiple historical and contemporary viewpoints within and across cultures related to important events, recurring dilemmas, and persistent issues, while employing empathy, skepticism, and critical judgment…”

- Individual Development and Identity: “…describe how family, religion, gender, ethnicity, nationality, socioeconomic status, and other group and cultural influences contribute to the development of a sense of self…have learners compare and evaluate the impact of stereotyping, conformity, acts of altruism, discrimination, and other behaviors on individuals and groups…”

- Individuals, Groups, and Institutions: “…help learners understand the concepts of role, status, and social class and use them in describing the connections and interactions of individuals, groups, and institutions in society…analyze groups and evaluate the influence of institutions, people, events, and cultures in both historical and contemporary settings…identify and analyze examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and efforts of groups and institutions to promote social conformity…”

- Power, Authority, and Governance: “…understanding the historical development of structures of power, authority, and governance and their evolving functions in contemporary American society… enable learners to examine the rights and responsibilities of the individual in relation to their families, their social groups, their community, and their nation… examine issues involving the rights, roles, and status of individuals in relation to the general welfare…explain conditions, actions, and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among nations…challenge learners to apply concepts such as power, role, status, justice, democratic values, and influence…”

- Civic Ideals and Practices: “…assist learners in understanding the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law…analyze and evaluate the influence of various forms of citizen action on public policy…evaluate the effectiveness of public opinion in influencing and shaping public policy development and decision-making…”

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- Note that both books contain excellent resources for future reading and research that should be explored.

- http://larecord.com/interviews/2014/01/10/pretty-in-ink-and-trina-robbins-she-was-unstoppable Trina Robbins, in an interview with Chris Ziegler shares fascinating background and research stories that will make the concept of research come alive for students.

- For page excerpts from Pretty in Ink: http://issuu.com/fantagraphics/docs/pretty-in-ink

- From 2018, an data evaluation of women working in comics by Tim Hanley on Comics Beat: https://www.comicsbeat.com/women-in-comics-by-the-numbers-summer-and-fall-2018/

Meryl Jaffe, PhD teaches visual literacy and critical reading at Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth Online Division and is the author of Raising a Reader! and Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning. She used to encourage the “classics” to the exclusion comics, but with her kids’ intervention, Meryl has become an avid graphic novel fan. She now incorporates them in her work, believing that the educational process must reflect the imagination and intellectual flexibility it hopes to nurture. In this monthly feature, Meryl and CBLDF hope to empower educators and encourage an ongoing dialogue promoting kids’ right to read while utilizing the rich educational opportunities graphic novels have to offer. Please continue the dialogue with your own comments, teaching, reading, or discussion ideas at meryl.jaffe@cbldf.org and please visit Dr. Jaffe at http://www.departingthe text.blogspot.com.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

All images (c) their respective creators and/or publishers.