Chinese cartoonist Wang Liming, also known as Rebel Pepper, is stranded in Japan on a temporary visa and turning to online supporters for financial help after his social media and retail sites were shut down, likely on orders from the Chinese government. Although Wang has been boldly speaking out via social media for years, he suspects the last straw was a cartoon in which he drew President Xi Jinping as a steamed bun.

Chinese cartoonist Wang Liming, also known as Rebel Pepper, is stranded in Japan on a temporary visa and turning to online supporters for financial help after his social media and retail sites were shut down, likely on orders from the Chinese government. Although Wang has been boldly speaking out via social media for years, he suspects the last straw was a cartoon in which he drew President Xi Jinping as a steamed bun.

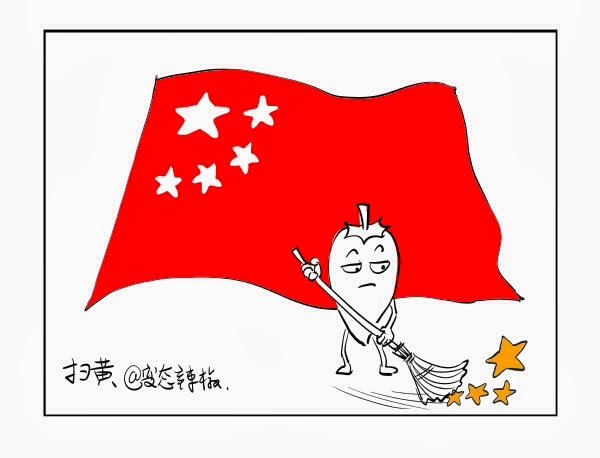

The culinary imagery was inspired by the nickname “Steamed Bun Xi,” which came into use on social media sites like Weibo and Tencent after the president made a grand show of visiting a humble steamed bun restaurant in 2013. Many Chinese netizens mockingly noted the similarity to the “regular folks” photo-op visits of American politicians to fast food restaurants, and a meme was born. In China, visual memes and wordplay like puns and nicknames are much more than amusing diversions; they are vital tools for evading censorship. As fast as the armies of in-house censors employed by social media companies can block keywords for whatever topic of discussion is displeasing to the government this week, subversive users come up with stand-ins.

So when Wang posted his cartoon showing other foods bowing before a pampered steamed bun in December 2013, it was a highly subversive act. His first clue that the government was not going to let it slide came months later, when his Tencent and Weibo accounts with hundreds of thousands of followers each were shut down without warning on the same day. A week later, his online shop on Alibaba-owned site Taobao followed. That account where he resold items from Japan to Chinese customers was his primary means of support, and since he happened to be in Japan at the time he concluded that he might be better off staying there.

Meanwhile, online government-controlled media websites were circulating an article that accused him of sharing “pro-Japanese remarks” on social media, and said that he “should be dealt with…according to the law. He should not be allowed to say whatever he wants to confuse people.” Wang got the message, he said:

They published this to intimidate me. This was a very clear signal from the government that if I went back I would have no online shop…no way to make a living, no freedom to work and that I would be punished.

Wang and his wife are currently staying in Japan on “cultural exchange” visas which are only valid through the end of the year; Japanese authorities have not allowed them to apply for political asylum. Saitama University gave him an unpaid position as a visiting scholar, along with a low-cost apartment, but the two are obliged to live off of their quickly-depleting savings and what little money Wang can earn from occasional freelance work. In desperation, last month he appealed to online supporters for help via PayPal or transfers to his Japanese bank account:

An Internet friend learned about my situation and encouraged me to set up a money collection. I’ve always felt embarrassed to do this, but now I have to give way to my impoverished state. I hope everyone sees me continuing to work and helps me from afar in my urgent situation. I also have a plan to make a series of graphic novels about modern and contemporary Chinese history, starting with an uncovering of June 4th. I hope everyone can continue to support me.

June 4th, by the way, is not just yesterday’s date; it’s the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the very mention of which is strictly forbidden in China. Although Wang could be sent back home at the end of the year if his options run out in Japan, he’s decided to throw caution to the wind: “If the government says I am an enemy of the state I will say whatever I want to say. I have nothing to lose any more.”

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.