Last week marked the 61st anniversary of the founding of the Comics Code Authority (CCA) and the implementation of the infamous series of rules, regulations, and guidelines that changed the entire face of the comic book industry. The Comics Code and the Comics Code Seal of Approval may now be defunct, but they had a lasting impact that can still be felt today.

In 1954, the Comics Magazine Association of America established the CCA — a group comprised of school officials, volunteer citizens, and publishers — as a last ditch effort to save an industry that had come under the vicious attack of parental organizations, child psychologists, and even the United States government for content many adults believed to be rotting the minds of America’s youth, converting them from upstanding citizens to emotionally maladjusted delinquents on the fast road to a life of crime and degradation. From horror and crime to superheroes and romance, comics became the direct target of magazine and newspaper articles, television broadcast specials, and “scientific” case studies, reports, and symposiums in a nation-wide battle to save and protect America’s children from what the U.S. Senate called “extremely cruel,” “sadistic,” and “lurid” publications.

In 1954, the Comics Magazine Association of America established the CCA — a group comprised of school officials, volunteer citizens, and publishers — as a last ditch effort to save an industry that had come under the vicious attack of parental organizations, child psychologists, and even the United States government for content many adults believed to be rotting the minds of America’s youth, converting them from upstanding citizens to emotionally maladjusted delinquents on the fast road to a life of crime and degradation. From horror and crime to superheroes and romance, comics became the direct target of magazine and newspaper articles, television broadcast specials, and “scientific” case studies, reports, and symposiums in a nation-wide battle to save and protect America’s children from what the U.S. Senate called “extremely cruel,” “sadistic,” and “lurid” publications.

The first attacks against comics, published in the late 1940s in magazines like Collier’s and Ladies Home Journal, sported bold headlines on their covers like “Do Comics Create Child Criminals?” and “Horror in the Nursery.” And other magazines, such as Time and Saturday Review of Literature, included summaries of findings from field experts like professor of education and director of the “Clinic for the Social Adjustment of the Gifted,” Harvey Zorbaugh, and the child psychologist out of Harlem, New York, who would be credited with writing the book that cemented the future of the comics industry, Fredric Wertham. Flashy stories like the “Psychopathology of Comic Books” and books like Wertham’s own Seduction of the Innocent reinforced arguments that comics corrupt and were the direct link to the statistical rise in youth violence and delinquency, and other pieces like “What can YOU do about Comic Books?” directly incited parents and teachers to take action against the rising epidemic of comic book consumption.

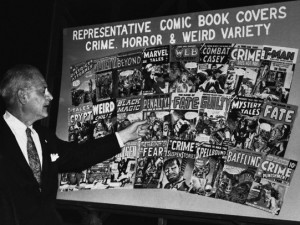

All of this media coverage culminated in a three-day hearing in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency in April of 1954. The hearing became a platform for experts to publicly announce both on television and on the radio the dangers of comics and parade through the courts publishers and comics creators that produced the amoral publications polluting American newsstands.

The conclusion reached after the hearing was that regulation of the industry and its editorial content needed to occur, and that regulatory body became the Comics Code Authority. As Joe Sergi wrote for CBLDF:

The conclusion reached after the hearing was that regulation of the industry and its editorial content needed to occur, and that regulatory body became the Comics Code Authority. As Joe Sergi wrote for CBLDF:

After the devastating Senate hearings, the comics industry was faced with an angry public and the fear of Congressional interference through adverse regulations. In response, the industry created the Comics Code Authority (CCA). Similar to the Association of Comic Magazine Publishers, the CCA sought to self-regulate comics. Essentially, the CCA sought to sanitize comics and eliminated the crime and horror genres. Essentially, comics for older teens and adult disappeared for nearly fifteen years.

“The comic-book medium, having come of age on the American cultural scene, must measure up to its responsibilities,” starts the Preamble for the Comics Code, the self-regulatory “guidelines” initiated by the CCA on October 26, 1954:

Constantly improving techniques and higher standards go hand in hand with these responsibilities…

In the same tradition, members of the industry must see to it that gains made in this medium are not lost and that violations of standards of good taste, which might tend toward corruption of the comic book as an instructive and wholesome form of entertainment, will be eliminated.

Therefore, the Comics Magazine Association of America, Inc. has adopted this code, and placed strong powers of enforcement in the hands of an independent code authority.

That independent authority was responsible for screening and requesting editorial changes to any comics that were destined for the newsstand. No retailer would dare put a comic on their racks unless they had the literal seal of approval by the CCA. In one of the largest instances of mandated censorship, comics were literally “legislate[d]… off the newsstands and out of the candy stores,” writes pop culture historian David Hajdu in his book The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How It Changed America.

Whereas some genres like funny animals, illustrated adaptations of classic literature, and other children-oriented books would leave the aftermath of the hearing virtually unscathed for their “wholesome” content, others were not so lucky.

Horror

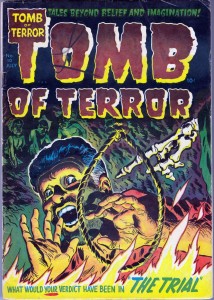

From EC Comics’ Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror to Harvey Publications’ Chamber of Chills and Tomb of Terror, no genre was more targeted and more directly affected by the Comics Code than horror. Before the Code, the success that EC saw with its own line of horror comics opened the door for virtually every publisher in business to have at least one horror comic on its monthly roster. Ajax-Farrell had Haunted Thrills, Charlton had The Thing, and Fawcett had This Magazine is Haunted.

From the in-house artists at EC to Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby, and Joe Simon, everyone worked on horror comics! “The horror comics were our favorites,” writes popular children’s author R.L Stine in the introduction to Jim Trombetta’s The Horror! The Horror! Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You to Read. “The art was amazing. The stories were ghastly and gruesome. They were written with something new to us: a wonderful combination of humor and horror.”

After the implementation of the Code, though, which prohibited the inclusion of words like “horror” or “terror” in the titles of comics as well the depiction of “evil” as something “alluring” the genre all but disappeared and has never quite been the same since.

Crime

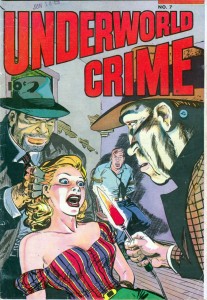

Another genre vehemently attacked by the American public and a direct target of the CCA, crime comics went from one of the most popularly published genres to one that virtually disappeared. Before the Code, any publisher worth their salt had a crime comic. EC had Shock SuspenStories and the infamous Crime SuspenStores, the latter of which was explicitly attacked during the 1954 Senate hearing for its questionable “good taste.” Lev Gleason Publications, who is credited with creating some of the first real crime comics, had Crime Does Not Pay and Crime and Punishment, and a smattering of smaller publishers capitalized on the crime trend with series like Crime Must Pay the Penalty (Junior Books), Thrilling Crime Cases (Star Publications), Underworld Crime (Fawcett), and The Perfect Crime (Cross Publications).

The series frequently declared that they told true stories with true facts and covered subjects from gangsters to serial killers. Each publisher tried to outdo the other with over-the-top depictions of murder and mayhem, but it was those attempts that landed the genre in hot water with the CCA and led to the whole first part of the Comics Code—General Standards, Part A—being dedicated to eliminating the glorification of crime and the “disrespectful” representation of police and judicial authorities.

Romance

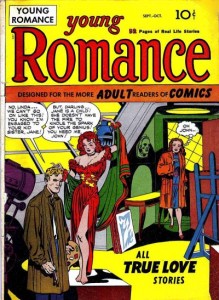

In order to reach the audience of girls and young women reading comics, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby of Captain America fame created what is credited as one of the first romance comics in 1947 — Young Romance (Crestwood Publications). Capitalizing on what were considered “real-life” stories of young American women, the genre quickly gained popularity and spawned whole other teen-oriented genres. From Flaming Love (Quality Publications) to Glamorous Romances (Ace Magazines) and Hollywood Confessions (St. Johns), romance comics appealed to readers of all ages and were the Harlequin Romance and Seventeen magazine of the day.

Like most pre-Code comics, though, not all romance comics were innocent tales of true love or young women coping with their husbands and boyfriends going off to war. Some romance comics could be as hot and spicy as the most popular romance books being printed today. From depictions of divorce, illicit affairs, and even murder in the name of love, romance comics ran the gamut from innocent tales of Hi-School Romance (Harvey Publications) to lurid secret lives: My Secret Affair (Fox Feature Syndicate), My Secret Life (Charlton), and My Secret Marriage (Superior Publishers Limited).

It was these aspects that made the genre a target of the CCA, specifically when it came to depicting the sanctity of marriage in a negative light. The Code set standards that called for the removal of any romance comic that “devalued” the home and/or would “stimulate the lower and baser emotions.” The Code also targeted explicitly the kinds of advertisements featured in romance comics, rejecting the advertisement of “sex or sex instruction books” and “medical, health, or toiletry products of questionable nature.”

Jungle Girls & Westerns

Two targeted genres that were never quite able to bounce back were the Jungle Girl and Western comics. Similar to most other comics before the Code, adventure was taken to the highest entertainment levels possible, with over-the-top action, graphic fights and death scenes, and in the case of jungle girls, sex appeal.

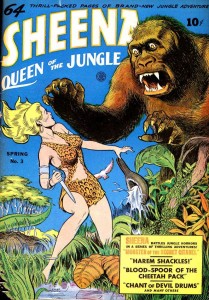

Although a significantly smaller group of comics compared to the glut of horror, crime, and romance comics coming out at the time the Code was instituted, readers who were interested in sexy ladies of the wild fighting beasts and falling in love could get their fill with Nyoka the Jungle Girl (Fawcett) and Rulah, Jungle Goddess (Fox Feature Syndicate). Some publishers gave the jungle theme a horror twist with comics like Terrors of the Jungle (Star Publications), but nothing was more successful than the tried-and-true scantily clad women as in probably the most notable jungle girl comic, Will Eisner and Jerry Iger’s Sheena, Queen of the Jungle (Fiction House).

Likewise, pre-Code the western genre saw a boost in interest with Badmen of the West (Magazine Enterprises) and Black Diamond Western (Lev Gleason Publications). Readers wanted the real-life tales of Billy the Kid, Buffalo Bill and the Cisco Kid. The West held the allure of a raw and untamed wilderness, and the gruff men who inhabited these spaces had a raw and untamed sense of justice that appealed to those interested in the Wild West, in the same way the crime genre appealed to those interested in the gritty gangsters of New York.

When the Code banned skimpy costumes and “suggestive and salacious” illustrations, though, jungle girl comics were out. And when the Code did away with unlawful behavior, Westerns went out too.

Superhero

Since the early 1930s, when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman, and especially around the time that the United States entered World War II, the superhero genre became one in which readers could relish stories of good versus evil and divorce themselves from the harsh realities of an increasingly violent world. From Captain America (Timely Comics, later Marvel Comics) and Captain Marvel (Fawcett Publications, now DC Comics) to The Blue Beetle (Fox Feature Syndicate), superheroes helped readers escape and in many cases also helped bolster patriotism.

After World War II, though, America had less need for the brightly colored super-men who did their part to help win the war. Although the Code didn’t explicitly target superheroes, it did target what superheroes meant to those who engaged in reading the books. Whether it be violence or vigilante behavior, superheroes where perceived as juvenile fantasies that distorted the minds of children. “One of the wonderfully appealing things about children is that they haven’t come to the age where reality and unreality are divorced,” declared news reporter Paul Coates in his 1955 television expose on comics, Confidential File. “The emotional impact of something they read in a comic-book may be much the same as a real-life situation they witness.” The allegation that comics and superheroes could distort children’s perceptions of reality is what led to the stricter enforcement of the Code on this genre. As Joe Sergi writes about some of the changes the Code enforced:

A lot of times, the changes were insignificant to the content of the story and comic creators creatively found ways around the Code. However… a lot of the time the stories had to be changed to the point where a) they didn’t make sense or b) they just weren’t as good. In all cases, the creator’s original vision was changed. That’s a shame.

Superhero comics fared better than most genres under the Comics Code, but they became pale shadows of Pre-Code titles, most suitable for only the youngest and most naive readers.

Where We Are Today

In 2011, the Comic Magazine Association of America officially dissolved when the last two holdouts — Archie Comics and DC Comics — decided to stop using the Seal. As publishers stopped heeding the Comics Code in the years leading up to its official dissolution, comics genres that had been suppressed and censored for decades were able to again grow and flourish. Some genres, like jungle girl, western, and romance, have seen little resurgence, the vestiges of those genres are apparent in recent adaptations of The Lone Ranger, Jonah Hex, and Jungle Girl as well as newer iterations of that were once relegated to the magazine format, such as Conan, Red Sonja and Dejah Thoris.

But other genres have flourished, notably the superhero genre, which has continued to be a dominant genre in the comics industry. Superhero comics diversified as the Code crumbled, featuring more sophisticated story lines and nuanced characterization that reflect societal changes and issues. Comics such as Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns deconstructed the superhero genre, drawing attention from audiences that previously weren’t as invested in comics, such as librarians and educators. The superhero genre has also found popularity in other formats, including television and cinema.

Horror and crime comics have also seen greater returns with the dissolution of the Code, whether it be Vertigo’s Hellblazer and The Sandman, Dark Horse’s Hellboy and BPRD, Marvel’s Ghost Rider, and Image’s The Walking Dead, all of which have found popularity beyond the comics format. Books like Frank Miller’s Sin City (Dark Horse) and Matt Wagner’s Grendel (Image) opened a door for contemporary crime comics, and creators like Ed Brubaker, Brian Azzarello, and John Wagner have all found success revitalizing the crime genre from its bland post-Code depictions of police officers doing their job to gritty investigative procedurals and psychological thrillers.

With the end of the most regulated era in comics history, the CMAA donated the official Comics Code Seal of Approval to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, and the symbol that stood for the censorship of decades’ worth of comics became one that is now used to protect and defend everyone’s right to free speech.

As Amy Kiste-Nyberg of Seton Hall University and author of Seal of Approval writes:

Today, publishers regulate the content of their own comics. The demise of the Comics Code Authority and its symbol, the Seal of Approval, marks elimination of industry-wide self-regulation, against which there is little legal recourse. Now, the comic book community can answer its critics by invoking its First Amendment rights, assisted by the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, whose mission is to protect those rights through legal referrals, representation, advice, assistance, and education.

Although the decades of censorship under Comics Code still looms over the comics industry, we see its influence dissolve more and more with each new comic published. Despite the Code’s legacy, we can still celebrate what it helped teach us about the value of free speech. Hopefully, it will take far less than another 61 years to see its effect pass away entirely!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Caitlin McCabe is an independent comics scholar who loves a good pre-code horror comic and the opportunity to spread her knowledge of the industry to those looking for a great story!