In celebration of Black History Month, CBLDF has partnered with Black Nerd Problems to spotlight Black comics creators and cartoonists who made significant contributions to free expression. Visit CBLDF.org throughout the month of February to learn more!

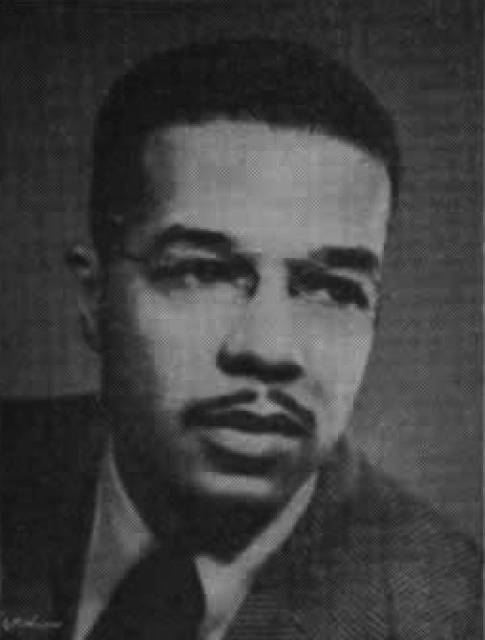

If you were to call Orrin C. Evans bold in the pursuits he enjoyed in his life, it would be like saying the monuments in Egypt are bigger than average. More than that, Evans’ life work wasn’t so much being bold as it was surviving the best way he knew how. A man whom The New York Times proclaimed “The Dean of Black Reporters,” Evans rose to a position of becoming one of the first comic book writers as an outsider to comics himself and stepped into a limelight that had scarcely seen the his like.

Evans’ roots in reporting, imaginative solutions, and unique perspectives began at home in the early 1900s. At the turn of the century in Pennsylvania, his family did well comparatively speaking. They lived in mostly white neighborhoods, thanks to his father working for the railroad and his mother being one of the first Black women to graduate from the Williamsport Teacher College. Despite that seemingly successful standing, things weren’t that way in the open, even in their own home. Evans’ father was lightly complected enough that he could and did pass for white at home and at work. In the presence of company, his mother would often keep up the facade that she was the maid of the household, all to protect the delicate foundation they wanted their kids to stand upon. Evans didn’t necessarily take this to heart as a pathway for him to go to school, get a job, and follow in their footsteps. Dogged by the urge to live as a writer, Evans dropped out of the 8th grade to pursue that passion.

Evans’ first gig was with The Sportsman’s Magazine before moving on to the Philadelphia Tribune, the oldest Black newspaper in the country. He would crossover into a mainstream viewership with the Philadelphia Record as its first Black writer to cover general assignments at a white newspaper. He drew accolades for speaking about segregation in the armed forces, but in 1944 — war time — it drew threats of violence too.

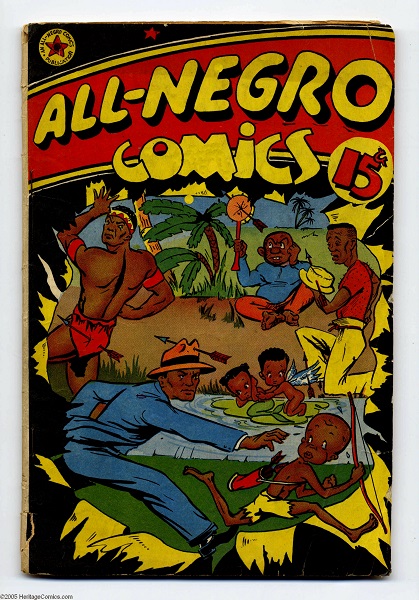

After the paper shut down in 1947, Orrin developed an interest in comic books, noting he might be able to widen his readership and still produce the same message he had as a journalist. He started to study comics more closely and realized that he didn’t see much representation in the heroes of most popular comics. He went to work on sculpting his own comic book and drew a number of past and present colleagues to aid in his vision. The result was All-Negro Comics.

All-Negro Comics #1 was released around June 1947. It presented a number of stories that depicted Black heroes and was produced entirely by Black creators. A second issue of All-Negro Comics #2 was planned, but is never saw print — vendors would not sell Evans paper for printing and distributors mysteriously pulled out.

Despite the success of All-Negro Comics and other comics focused on Black issues, such as Parents Magazine’s Negro Heroes and Fawcett’s Negro Romance, the books did not start the groundswell some anticipated for more Black comic books. There were small snapshots of Black characters in comics over the years, very few of any real relevance. It wasn’t until the mid 1960s that Black Panther finally debuted as a Black protagonist for a major publisher, and of course, being created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, didn’t include any Black creators at the time.

Before Evans died in 1971, he created a legacy as a legendary newspaper man, one that stood out among his White colleagues by covering stories and events dealing with the Black experience that many did not have the gumption or perspective to cover. But he also opened up a portal in comic books that flew as a direct challenge to the White hero default. The many battles fought today concerning representation in comics began with Evans, who had no twitter coalition or public opinion at his back, just sheer will to see himself in the stories he loved to read.

For more on Orrin Evans, visit “Orrin C Evans and the story of All Negro Comics” by Tom Christopher.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

William H. Evans is Editor-in-Chief for Black Nerd Problems.