The year was 1954. The location: Glasgow, Scotland’s Southern Necropolis, a massive graveyard harboring over 250,000 sets of mortal remains. Over a span of three nights that September hundreds of children under the age of 14 reportedly assembled there with makeshift weapons, ready to take on a vampire they had conjured from their own collective imagination. That would be bizarre enough, but then adults blamed the unusual behavior on their own particular bogeyman: American horror comics.

The year was 1954. The location: Glasgow, Scotland’s Southern Necropolis, a massive graveyard harboring over 250,000 sets of mortal remains. Over a span of three nights that September hundreds of children under the age of 14 reportedly assembled there with makeshift weapons, ready to take on a vampire they had conjured from their own collective imagination. That would be bizarre enough, but then adults blamed the unusual behavior on their own particular bogeyman: American horror comics.

The fantastic story of the Gorbals Vampire was recounted in a BBC Radio 4 documentary in 2010, including interviews with some of the now middle-aged former vigilantes. Rumors had run through Glasgow schoolyards that a seven foot tall vampire with iron teeth and a taste for children was on the prowl in the area. He had already eaten two boys, they believed despite the fact that none were missing, and would certainly come for more unless he was stopped. Adults proved typically useless in this scenario, so they took matters into their own hands.

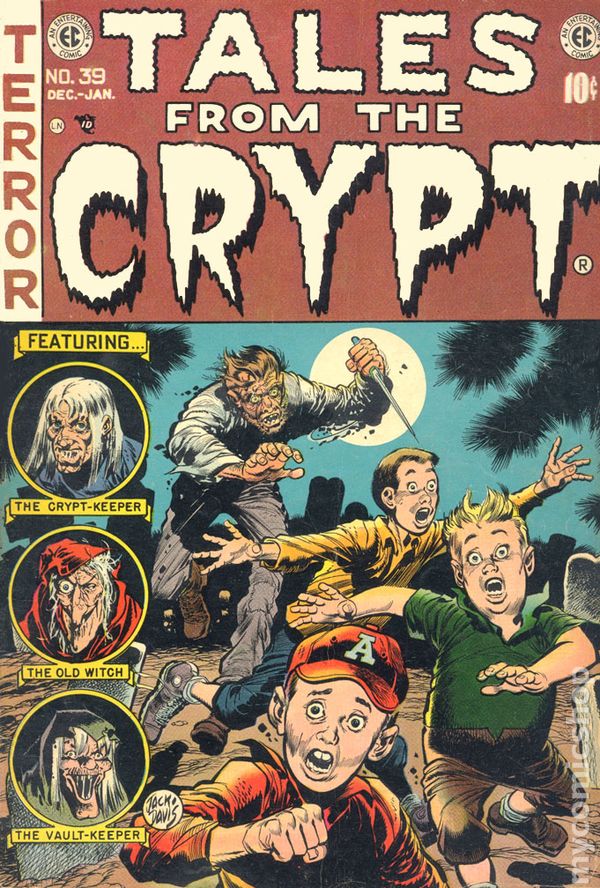

Despite being dispersed by police and a local school headmaster the first night, the pint-sized mob converged on the cemetery for two more nights after that. That was enough time for the story to catch fire in local and national newspapers, which sought an explanation for the children’s unshakeable belief in the vampire. Anti-comics crusaders seized their opportunity, claiming that the seed had been planted by “terrifying and corrupt” horror titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror.

Never mind that horror comics were already difficult to obtain in Scotland, and locally produced fare tended to the “squeaky clean” like The Beano and The Dandy. Never mind also that the specific detail of the iron teeth was associated not with a monster from comics, but from the Bible as well as “a poem taught in local schools.” The Gorbals Vampire Affair provided convenient fuel for those who wanted comics regulated by the government. Unlike in the U.S. where the industry pre-emptively policed itself with the Comics Code, the U.K. censors succeeded in 1955 when Parliament passed the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act. The law, technically still in force today although largely ignored, bans the sale of comics and magazines portraying “incidents of a repulsive or horrible nature” to minors.

That law may seem like a quaint vestige of the 1950s, but it had a relatively recent echo in 2007 when the city of Beijing labelled Death Note an “illegal terrifying publication” and banned its sale at newsstands after parents and teachers complained that children were “spending too much time on reading the horror stories and not enough time on studying.” In both cases, perhaps the adults could have benefitted from the same imagination workout their children got from leisure reading!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.