Happy Women’s History Month! All through March, we’ll be celebrating women who changed free expression in comics. Check back here every week for biographical snippets on female creators who have pushed the boundaries of the format and/or seen their work challenged or banned.

Jessica Abel

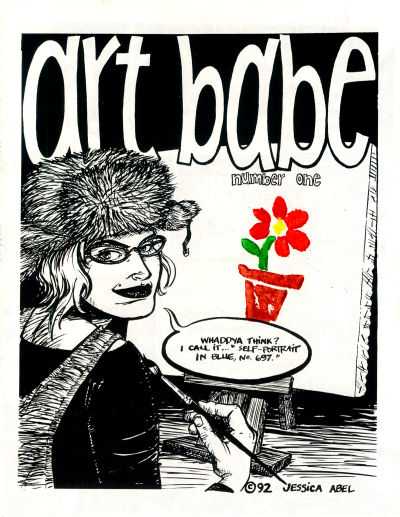

The underground comix movement may have ended, but 1990s artist Jessica Abel would not only find her voice in one of the remaining vestiges of that time—the zine—but she would become a true pioneer of the genre that we now embrace as alternative comics and someone dedicated to bringing comics into school curriculum.

The award-winning artist got her start in comics in 1992 by photocopying and hand-sewing individual issues of her zine Artbabe. A series of individual non-fiction stories that told the tales of native Chicagoans like herself, these hand-crafted, self-published comics were the roots of what would become standard fare at SPX (Small Press Expo) and APE (Alternative Press Expo) today.

Jessica Abel was an original indie creator, embracing the autobiographical narrative form and using comics not only as a means to tell her story, but to comment upon the medium itself. After receiving the 1995 Xeric Award, Abel would have her entire run of Artbabe published. From there, she would become one of the biggest voices of the alternative comics scene.

Since Artbabe, the self-proclaimed “super narrative geek” has continued to hone her craft and publish a wide variety of works on a crazy number of different topics. From a book about the masters of radio, to the story of a hoverderby player on Mars, for Abel the narrative power of comics is what makes them so unique and important. “In a lot of ways, my story is all about investigating story,” says Abel. “I love finding systems, strategies, and tools that allow me to make the strongest stories possible. It helps that I’m intense and long-sighted, with a gift for understanding deep narrative structure.”

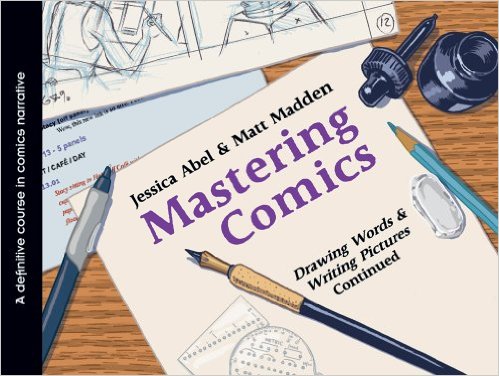

Although Abel has spent decades writing and drawing comics telling her own story, she has also dedicated the past several years to educating others and helping them find their narrative voices. Whether it be teaching at the School of Visual Arts or making books that are dedicated to mastering the craft of comics, along with being a pioneer in the alternative comics scene, Abel has also been a pioneer of comics in the classroom. Comics may have been perceived as kiddie-fodder in the 1950s, but it has become Abel’s mission to show that comics as a narrative form can do so much more and means so much more to creators today:

We all can find ourselves deep in the dark forest of creative crisis when in the midst of making an ambitious story, and I work together with narrative artists to find their own, unique path out of the forest and to a brighter, better, stronger story.

Abel may have started with zines, but she has certainly influenced the way that so many new creators tell their personal stories today, and she has also helped lay the groundwork for using graphic novels in the classroom. Her decades of pounding the pavement have opened new doors both within and outside the comics industry.

–by Caitlin McCabe

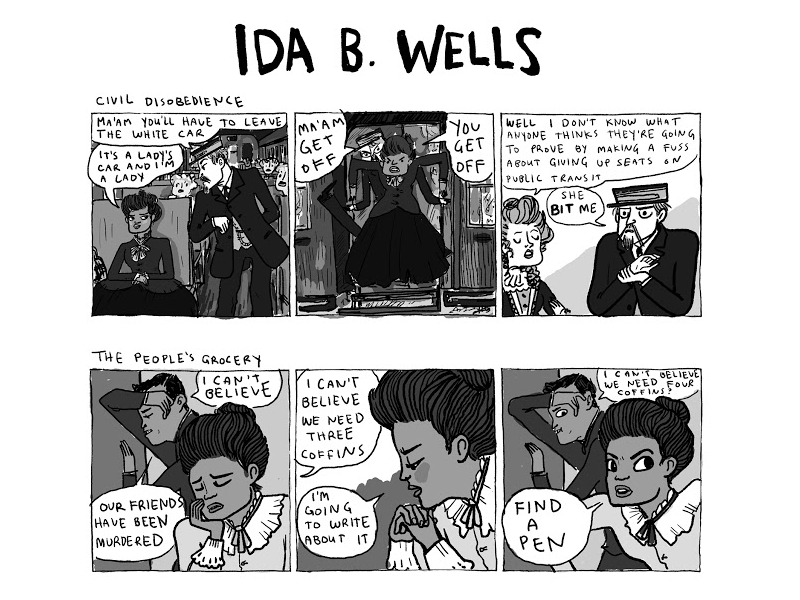

Kate Beaton

As a self-taught comic creator from the first generation to come of age on the Internet, Kate Beaton first shared her comics online simply as a way to stay in touch with distant friends. Before long this placed her among the pantheon of webcomics pioneers, but her sustained success in the years since is entirely due to her unique facility for comic timing, facial expressions, and historical humor that is both zany and erudite. According to publisher Peggy Burns of Drawn & Quarterly, which has released two bestselling Beaton collections, “she should be a national treasure. Everyone in Canada should know who Kate Beaton is.”

As a self-taught comic creator from the first generation to come of age on the Internet, Kate Beaton first shared her comics online simply as a way to stay in touch with distant friends. Before long this placed her among the pantheon of webcomics pioneers, but her sustained success in the years since is entirely due to her unique facility for comic timing, facial expressions, and historical humor that is both zany and erudite. According to publisher Peggy Burns of Drawn & Quarterly, which has released two bestselling Beaton collections, “she should be a national treasure. Everyone in Canada should know who Kate Beaton is.”

Beaton was born in 1983 in the tiny coastal village of Mabou, Nova Scotia. Growing up in the tight-knit rural community, she was recognized early on as one of a few students in her class cohort of 23 who could draw. With no art classes offered at the local K-12 school, Beaton’s parents cultivated her natural talent by getting her involved in 4-H and by introducing her to local artists. In those days her exposure to comics was mostly through the strips that happened to run in the newspaper, the Foxtrot collections which she bought at school book fairs, and the old Peanuts books in the school library–where she discovered both that Charles Schulz’s style had changed over time, and that she preferred the older strips.

Beaton also had a lifelong interest in history and spent summers in her teen years working in museums or archives. While attending Mount Allison University, where she majored in History and Anthropology, she submitted comics to the student newspaper and eventually became editor of the comics section. She relished the chance to flex her creative muscles and to finally get informed feedback for her work, she told The Comics Journal’s Chris Mautner in an interview:

You could put anything you wanted in there. And I did. And I got good attention for it. I knew that it was everybody’s favorite part of the paper. I knew that everybody read the comics section. I knew that if people found out that I was the one behind this one comic or the humor column they would get excited, that’s a rush when you’ve spent your whole life drawing without anybody really paying attention.

After college, though, Beaton again found herself without an audience. To pay off her student loan, she did office work for a year at a remote mining site in the Alberta oil sands. The next year she found a job she loved as an administrative assistant at the Maritime Museum of British Columbia in Victoria, but regretfully had to leave when they were unable to offer more than part-time hours. She returned to the oil sands for another year, even though the work was soul-deadening. To cheer herself up in the evenings she worked on pencil-and-ink comics and, encouraged by friends from college and back in Victoria, used the office scanner to upload them to LiveJournal and the nascent Facebook.

By that time Beaton’s work had begun to pivot away from the more personal and contemporary comics she did early on, and towards what she is most known for today: quirky but informative spoofs of historic figures and classic literature. She soon amassed a devoted following, and was surprised to find herself at the vanguard of a new format: webcomics. In 2008 she moved her work to her own website, Hark! A Vagrant, and took the plunge of working on comics full-time. She credits her merchandising partnership with Topatoco, which lasts to this day, with allowing her to support herself through comics and to gauge her audience in those early days.

In 2009 Beaton self-published her first book, Never Learn Anything From History, and was more than a little embarrassed when her signing line at SPX dwarfed those of more established creators. She also became an unwilling symbol of the alleged battle between webcomics and print, she told Mautner:

When I came in it was ‘Print vs. Web! Who’s cool and who’s legit and who’s not or who deserves what.’ I never had invested in any part of comics culture at all. So it was like coming in and looking into the glass window and seeing all this kerfuffle that I just watched it with interest. I didn’t identify with either side.

Beaton’s blockbuster success continued with her next book, Hark! A Vagrant, published by Drawn & Quarterly in 2011. Time critic Lev Grossman described it as “the wittiest book of the year,” while Toronto Globe & Mail’s Martin Levin said it was “one of the most innovative and delightful collections I’ve come across.” The book spent five months on the New York Times bestseller list, and Beaton won a total of four Harvey Awards in 2011 and 2012, including overall Best Cartoonist the second year.

During this time Beaton lived in Brooklyn and Toronto, also ticking off a longtime goal of having some cartoons published in The New Yorker. For her second collection in 2015 titled Step Aside, Pops, Drawn & Quarterly ordered its largest-ever first printing of 50,000 copies. Also in 2015, she broke into children’s books with The Princess and the Pony, the tale of a young warrior princess and her rotund, flatulent steed. A second picture book with Scholastic, King Baby (inspired by Beaton’s nephew Malcolm), is slated for Fall 2016. She continues to post historical comics on Hark! A Vagrant, as well as occasional sketches of her visits home on Tumblr and Twitter.

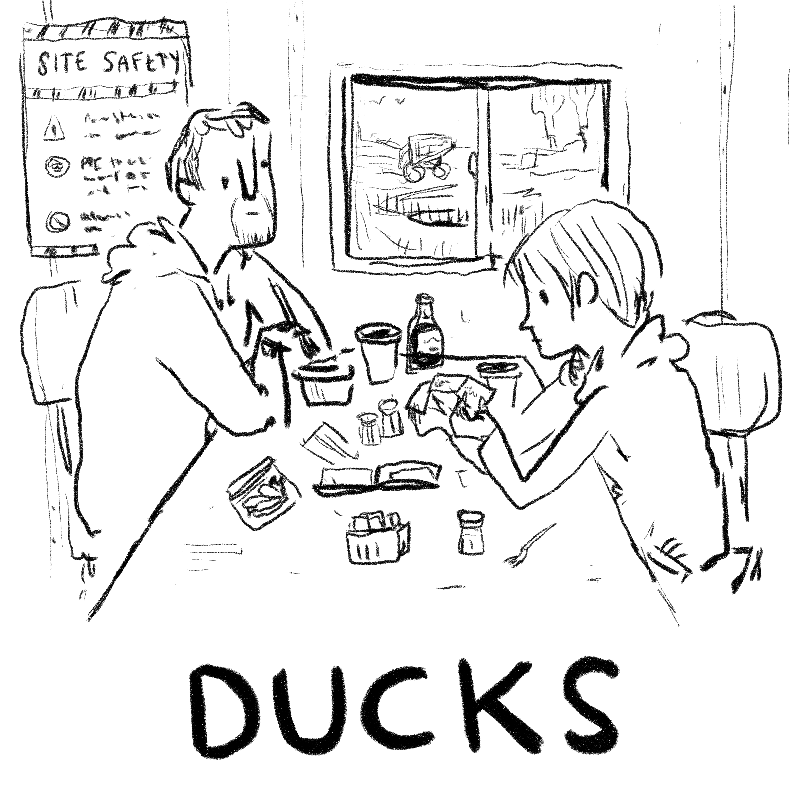

Late last year, Beaton moved from Toronto back to Mabou, where she says the residents are “immensely proud” of her success and the post office sells her books, supplied by her mother via Amazon. Her next project, she recently said on Twitter, may be a graphic memoir of her time working in the oil sands, an expansion of a previous five-part Tumblr comic called Ducks which reflected on the impact of oil drilling for both the environment and the workers. Despite widespread praise from critics, fans, and colleagues alike, she told Mautner that her status as a groundbreaking creator still hasn’t quite sunk in:

I don’t think that I ever got used to [success] in some ways. And in some ways, it happened so fast that I don’t completely trust it – will it go just as fast? But then, it might just be my nature, I’m a worrier. I don’t feel like I have done the thing yet that solidifies my place in the world. Where I can take that breath and look back and think, ‘OK, you did it.’ I’m happy for success but I’m not much good at reveling in it. There’s comics to make.

–by Maren Williams

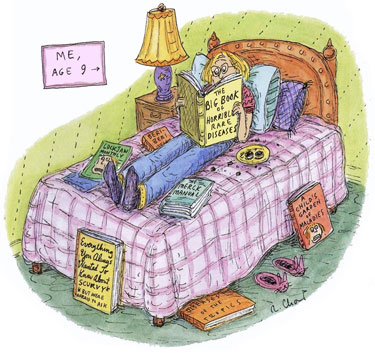

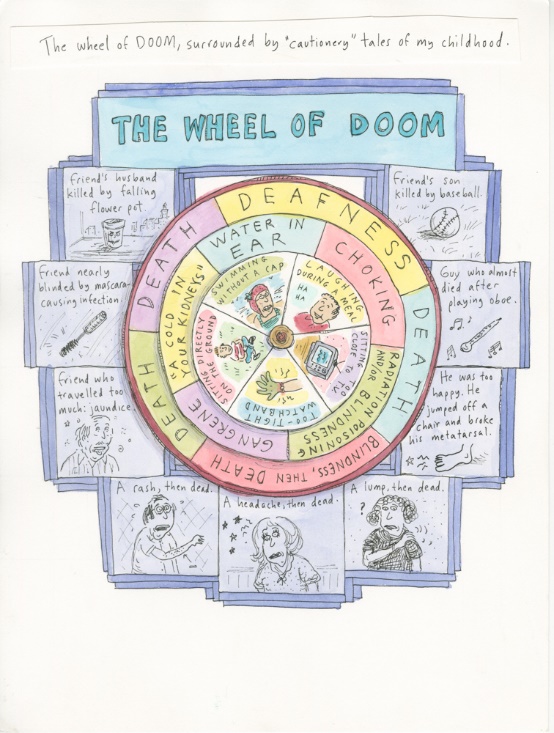

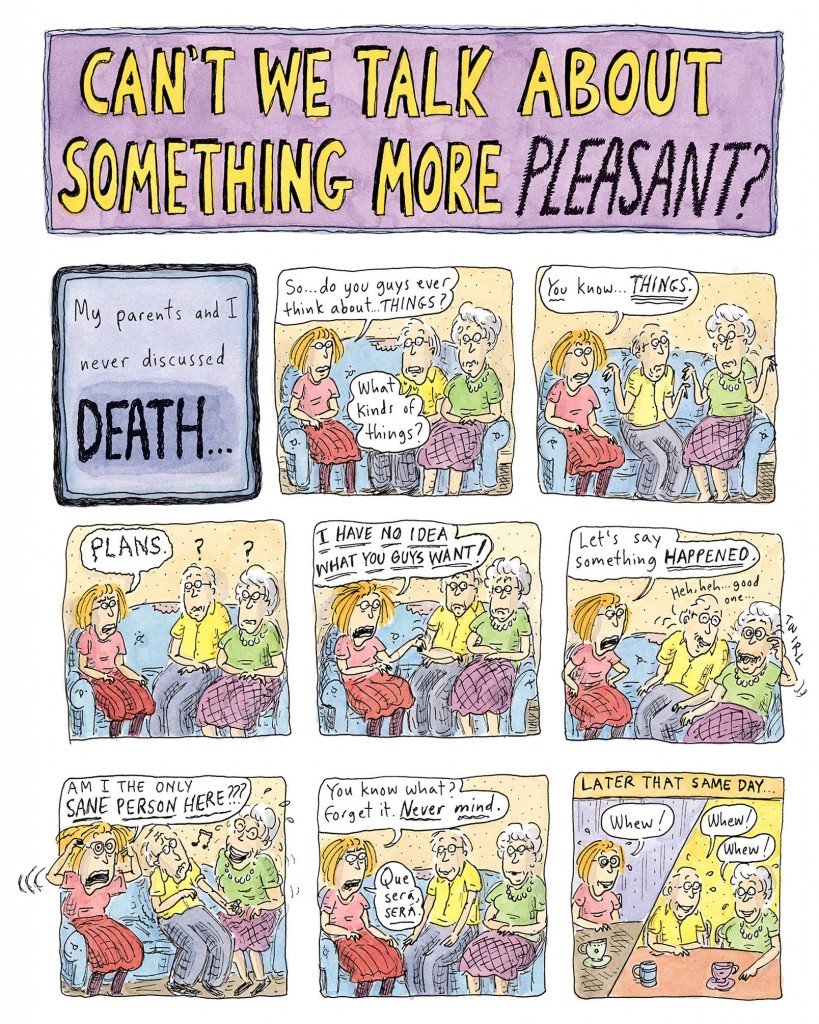

Roz Chast

Since 1978 Rosalind “Roz” Chast’s cartoons have graced the pages of The New Yorker along with numerous other publications. Called “the magazine’s only certifiable genius” by Editor David Remnick, the award-winning cartoonist, author, and children’s book illustrator has made a career out of depicting the raw and real aspects of her own life and, by extension, ours. From Theories of Everything and The Alphabet from A to Y with Bonus Letter Z! to her graphic memoir Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, which tackles her parent’s deaths, Chast has mastered the craft of balancing comedy with reality and dominated the highly competitive professional field of editorial cartoons.

Having a fondness for drawing and a unique curiosity about the world from an early age, the native New Yorker saw art and humor as a way to make sense of her mortality, and it is that humorous and honest approach to topics like life, death, and the ordinary and mundane that have made her a voice that resonates with so many people. “I’ve done a lot of death cartoons – tombstones, Grim Reaper, illness, obituaries…,” said the cartoonist in an interview with Forbesmagazine. “I’m not great at analyzing things, but my guess is that maybe the only relief from the terror of being alive is jokes.”

Delving into editorial cartooning in the 1970s, Chast faced obstacles that many young women did during that time – proving that they had they had what it took, that their age wasn’t an issue, and that they had something new and different to say. Chast had all of these things and more. In fact, her unique approach to cartooning is what has set her apart and above many other cartoonists doing work then and even today. “Being female was just one more way I felt different and weird,” recalls Chast. “I was also a young ‘un, and also my cartoons were not like typical New Yorker cartoons.”

Her greatest and most personal work to date, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, is the finest mix of humor and being human. Tackling the difficult subject of death by telling the story of her parents’ last years alive, Chast shows the one of the saddest parts about being human through a lens of humor, building a truly unique narrative not many can emulate and one that you can’t help but read.

From black-and-white panels to full-color covers and spreads, magazine cartoons or graphic memoirs, if there is a story to tell, despite the obstacles and sensitivity of the topic, Chast has adapted her skills and honed her craft to get that story told. The award winning cartoonist has been recognized both within and outside the cartoonist community as an indomitable force who won’t let decorum stifle her voice.

—by Caitlin McCabe

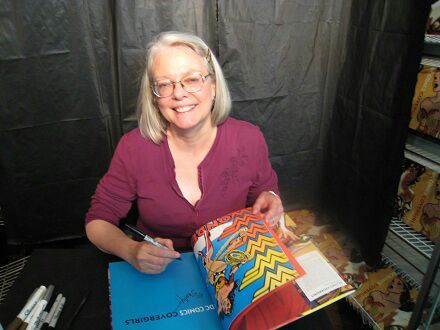

Colleen Doran

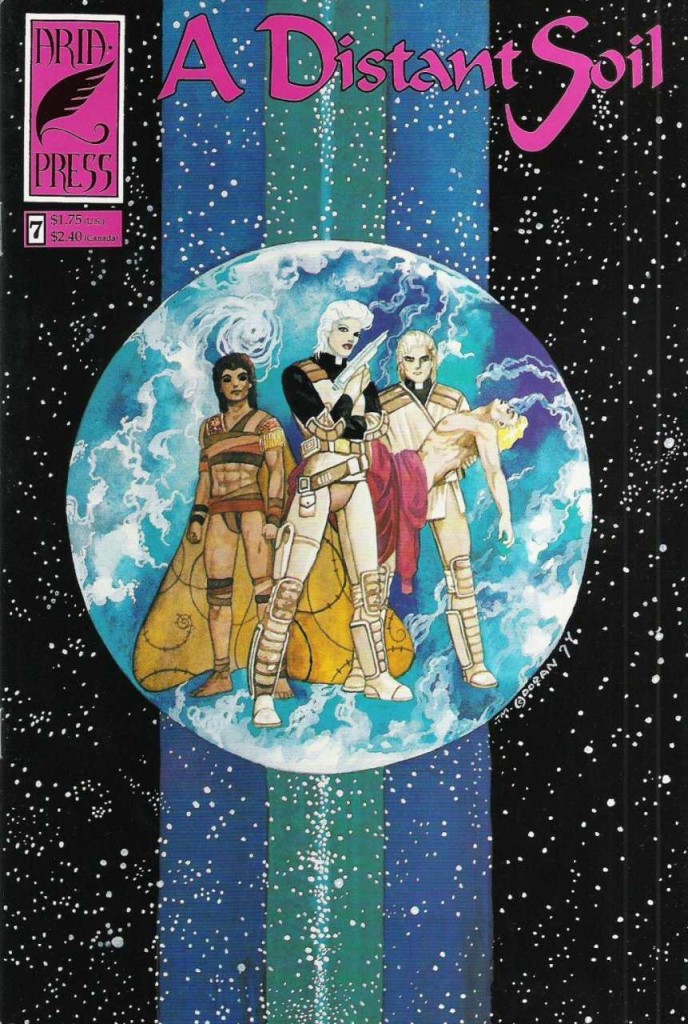

Colleen Doran started out as an exceptionally precocious artist, winning a Disney art contest at the age of five in the late 1960s. At that time she had every intention of eventually becoming an animator, but also felt pulled to comics. At 12 years old, a lengthy bout with pneumonia unexpectedly cemented her career track in two ways: a friend of her father’s gifted her a huge box of comics to read while bedridden, and she also had lots of time to write and draw her own creations. It was at that early juncture that she began work on her long-running independent series A Distant Soil, which has since become a touchstone in self-published comics.

At 15 Doran attended her first science fiction convention. Impressed by the fanart she saw there the first day, she returned with her own work the following day and sold out. By the time she went to college, she was already working fulltime as an artist and A Distant Soil was being published by WaRP Graphics. After the publisher attempted to claim full copyright on her work, however, Doran left WaRP and started the series over again at Starblaze Graphics, an imprint of the Donning Company.

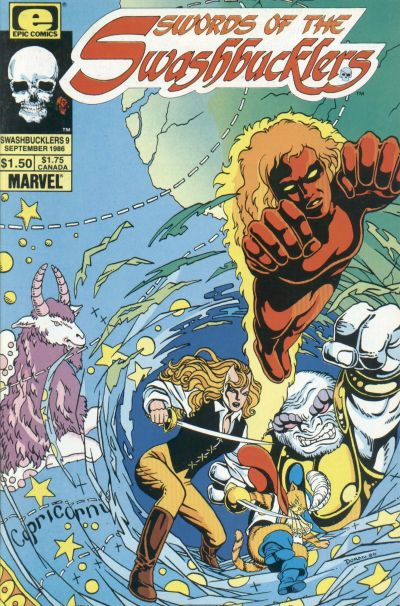

After Donning in turn went out of business, Doran worked for a time on major properties including Amazing Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, The Sandman, and Legion of Superheroes. A Marvel adventure comic she illustrated in 1986, Swords of the Swashbucklers #9, was one of the books seized in the police raid of Friendly Frank’s comic shop which led to the establishment of CBLDF. The issue was reportedly targeted due to lesbian themes, but ultimately was dropped from the case before store manager Michael Correa was prosecuted and convicted for display of obscene materials.

Having been burned in her previous attempts to find a publisher for A Distant Soil, in 1991 Doran decided to take on the job herself. Through her own company Aria Press she re-released the issues that had been published by now-defunct Donning, then continued the story with new material. In 1995 the series was picked up by Image Comics, which still publishes it to this day.

Heavily influenced by manga, A Distant Soil was among the first U.S. comics to feature openly LGBT characters. In a 1995 interview in Comics Buyer’s Guide, Doran said she saw no reason not to include fully rounded characters of all orientations:

I thought I was pretty obvious. Rieken and D’mer are lovers and bisexual…. I do plan to explore gay rights concerns at greater length in the future. Gay rights are human rights and I don’t care if people think I’m a lesbian. Just shows how homophobic they are. Like straight people can’t support gay rights! That’s like saying men can’t be feminists! Really stupid.

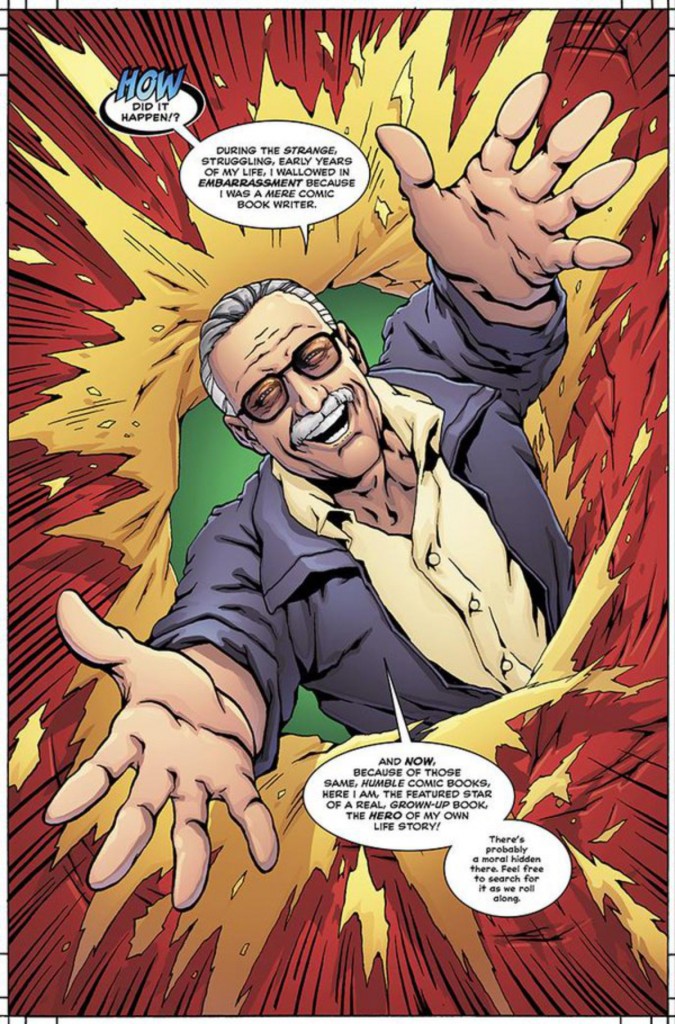

Doran’s recent portfolio is as diverse as ever. In 2012 she illustrated the multi-generational Irish American family saga Gone to Amerikay, written by Derek McCulloch. Last year, it was Stan Lee’s memoir Amazing Fantastic Incredible, and her next major project, coming this fall, is a graphic novel adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s short story “Troll Bridge.” In between there have been covers for The Walking Dead, Squirrel Girl, and S.H.I.E.L.D., among many others. On top of all her creative achievements, Doran is also now credited as a pioneer in comics self-publishing, and continues to advocate tirelessly for creators’ rights to their own work.

–by Maren Williams

Posy Simmonds

Rosemary Simmonds, nicknamed Posy, was born in 1945 and grew up on her family’s dairy farm in Berkshire, England. The middle of five children in a well-off family, she stoked her artistic talent early by browsing back issues of the touchstone satirical magazine Punch. She soon learned, she later recalled in an interview in The Guardian, “that if I drew a fairy very well people would say it was good. But if I then made her smoke a cigarette people would laugh.”

After attaining high marks at boarding school, Simmonds studied art at the Sorbonne in Paris and the Central School of Art and Design in London. After obtaining her degree, she made a meager living off of freelance illustration, later telling The Guardian’s Nicholas Wroe that her best-paying gigs were forReader’s Digest, which gave artists “wonderful instructions: ‘No smoking, no drinking, no sex, no big noses.’” In 1969 she debuted a daily comic strip called Bearin the tabloid paper The Sun, and subsequently worked her way into more highbrow publications such as Cosmopolitan, Harper’s, and The Guardian itself, which would become her home base over the following decades.

From 1977 to 1987, The Guardian ran Simmonds’ strip Posy, which skewered the British bourgeoisie that was her own milieu. One reviewer, assessing a collected edition of the strips, predicted that “in a hundred years’ time, she will be required reading for social historians” because of her talent for loading characters down with subtle status symbols and convincingly portraying their way of speaking. Simmonds also continued freelance illustrations for periodicals and published several offbeat and inventive children’s picture books such as Fred, about two siblings who discover that their recently deceased cat led a secret life as a feline rock star.

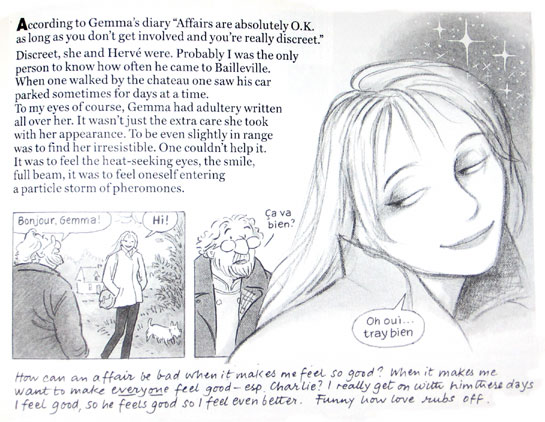

In 1999 Simmonds broke new ground with Gemma Bovery, a graphic novel update of and homage to Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Much like the original Emma Bovary, Simmonds’ bored adulteress eventually meets a tragic end–but Gemma Bovery is a modern-day middle-class Englishwoman living in France, and reviewer David Hughes proclaimed that the book encapsulates “all that ever needs to be said about the English trying to settle in France, the unsettling nature of the French, the nature of culture clash, lurk[ing] with sly hilarity.”

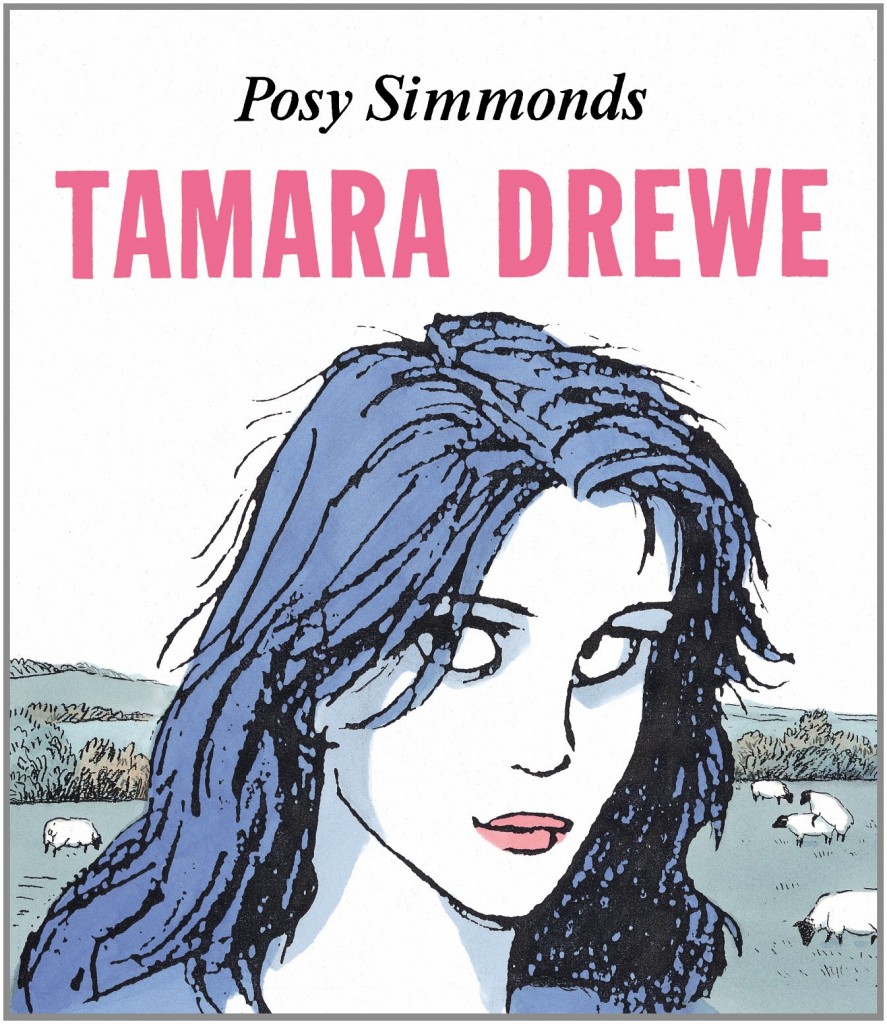

Gemma Bovery was initially serialized in The Guardian before it was released in book form, a pattern Simmonds repeated with her next graphic novel Tamara Drewe in 2007. This was also inspired by a classic novel, Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd, but that parentage is less obvious than in Gemma Bovery. A review in The New Yorker compared the book’s “lushly realistic drawings and complex female characters” to those of Alison Bechdel, but added that Simmonds’ “learned references and her ear for a variegated British vernacular make her unique.”

In recent years Simmonds has continued to do freelance illustrations and cartoons for various periodicals, and is now lauded as one of the bright lights of British cartooning. In 2012 her work was featured in a large exhibition at the Belgian Comics Centre in Brussels, and last year she was invited to present a career retrospective at the Queen’s Gallery in the Buckingham Palace complex.

—by Maren Williams

Louise Simonson

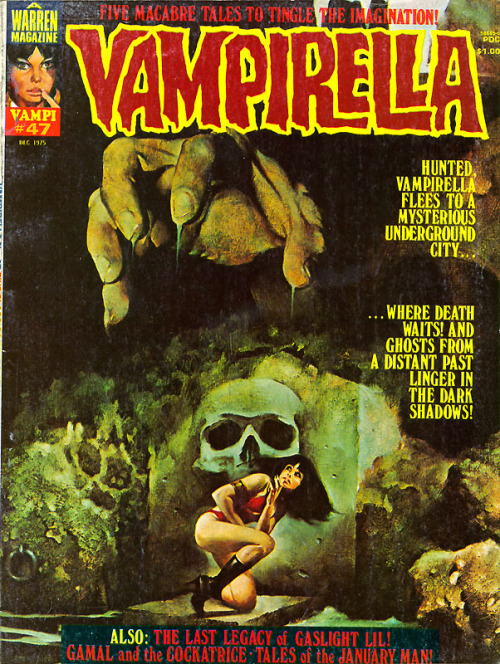

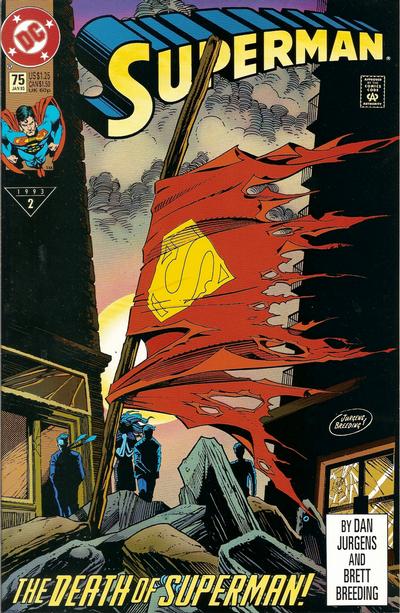

“Girls can have their own clubs, too.” This is how extraordinary comics editor and writer Louise Simonson described the comics industry in a 2011 interview. Never one to be held back or let socially assumed boundaries define what she could and could not do in comics, Simonson worked as an editor for Warren Publishing in the 1970s, created Power Pack and edited Marvel’s X-books in the ’80s, and played a major role in constructing the seminal “The Death of Superman” storyline in the ’90s. According to Comics Alliance:

Louise Simonson has influenced superhero comics to a degree that few women have… [and] while Simonson is no longer writing at the heart of superhero comics, her influence still echoes through DC and Marvel alike.

Simonson got her start in the industry in 1974 in the production department and later as an assistant editor for the historically important publisher, Warren Publishing—the publisher who bypassed the Comics Code by producing horror comic “magazines.” After working at Warren for almost a decade, in 1982 when Editor Bill Dubay left, Simonson issued a challenge to publisher James Warren: “Look, I will edit the line for six months on my Assistant Editor salary and I will get it done, I will get it done on schedule.” Not only did she become editor of the full line of books, but she was made a Vice President. “I was a big fish in a little itty bitty pond,” is how the writer describes her experience at Warren.

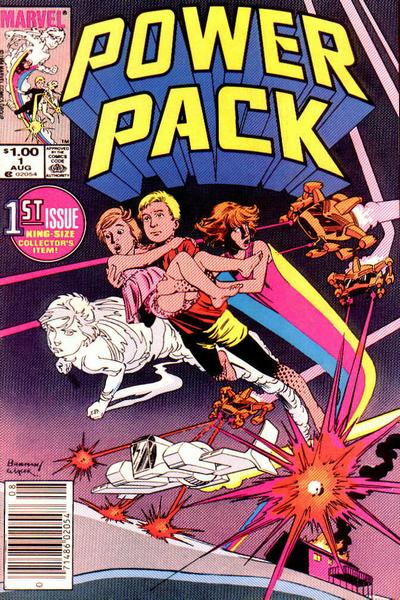

Simonson was a powerhouse and her tenacity and chutzpah got her noticed by Marvel in the early ’80s. Hired by Jim Shooter to edit the line of X-books includingUncanny X-Men, X-Factor, and The New Mutants, Simonson quickly jumped into the writing pool in 1984 creating Power Pack.

In the ’90s she began working for DC where she helped launch Superman: The Man of Steel and later played a significant role in the construction of the “Death of Superman” storyline.

From Warren, to Marvel, to DC, and a long list of other publishers, Simonson never let the preconceived baggage of being a woman prevent her from telling the kind of stories she wanted. In fact, she saw that “baggage” as an opportunity to prove that she was better than any male editor or writer in any boys’ club. “Honestly, I think the women who make it in superhero comics don’t make it because they’re as good as the guys,” said Simonson. “They make it because they’re better than the guys. You have to be. You have to be smarter, you have to work harder…”

All of the smarts and hard work Simonson put into the comics industry over the last 40 years have made her one of the industry’s most successful and influential writers in the contemporary superhero genre and comics in general.

–by Caitlin McCabe

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!