Happy Women’s History Month! All through March, we’ll be celebrating women who changed free expression in comics. Check back here every week for biographical snippets on female creators who have pushed the boundaries of the format and/or seen their work challenged or banned.

Grace Drayton and Margaret Gebbie Hays

Today, we examine the work of a sister act: Grace Drayton and Margaret Gebbie Hays, whose comics of cherubic, misbehaving children would help define not just the comics pages for decades, but would have a lasting impact in the world of advertising. Their influence can be felt even today, echoing in the Japanese style of kawaii, or cuteness.

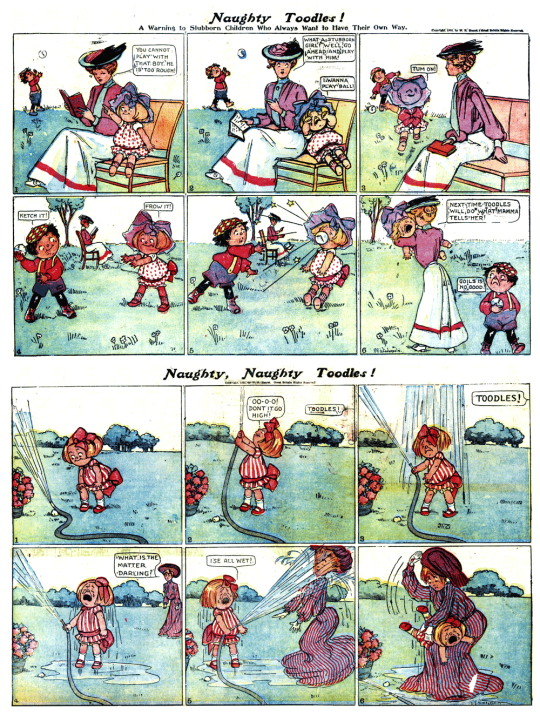

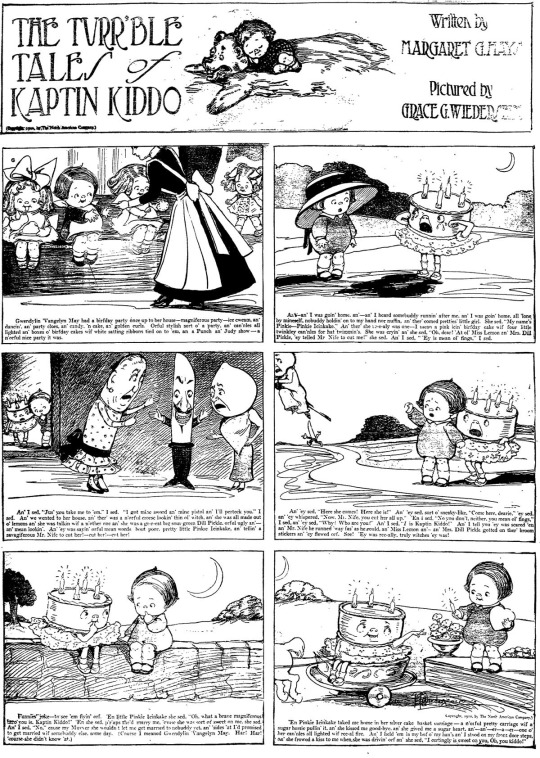

Drayton, who worked for several years under her first husband’s name Wiederseim, would begin her foray into the comics pages with Naughty Toodles (1903), becoming the first woman cartoonist on the Hearst Syndicate. She would also produce cartoons such as Dolly Dingle and Dolly Dimples. Together, Drayton and Hays created The Adventures of Dolly Drake and Bobby Blake in Storyland (1905) and The Turr’ble Tales of Kaptin Kiddo (1909). Drayton and Hays’ work featured cute, round-faced and rotund tots whose independent spirit meant they frequently found themselves in a tight spot. The dialogue, too, reflected this cuteness, utilizing exaggerated baby talk and childish dialect.

Drayton, who worked for several years under her first husband’s name Wiederseim, would begin her foray into the comics pages with Naughty Toodles (1903), becoming the first woman cartoonist on the Hearst Syndicate. She would also produce cartoons such as Dolly Dingle and Dolly Dimples. Together, Drayton and Hays created The Adventures of Dolly Drake and Bobby Blake in Storyland (1905) and The Turr’ble Tales of Kaptin Kiddo (1909). Drayton and Hays’ work featured cute, round-faced and rotund tots whose independent spirit meant they frequently found themselves in a tight spot. The dialogue, too, reflected this cuteness, utilizing exaggerated baby talk and childish dialect.

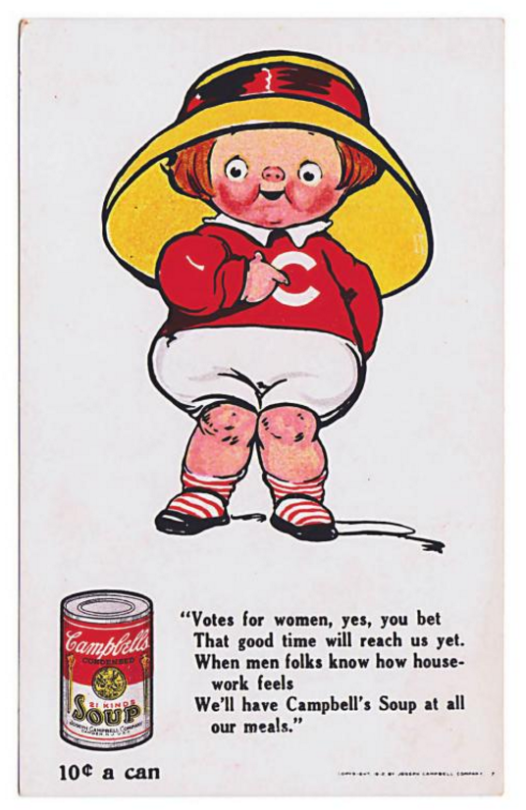

Drayton would find her greatest fame in commercial art with the Campbell’s Soup kids. In 1904, her then-husband Theodore Wiederseim submitted an advertising proposal to Campbell’s that featured some of Drayton’s wide-eyed children. Executives loved it, and Drayton’s work was soon featured on the sides of streetcars and in prominent magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post.

Drayton would find her greatest fame in commercial art with the Campbell’s Soup kids. In 1904, her then-husband Theodore Wiederseim submitted an advertising proposal to Campbell’s that featured some of Drayton’s wide-eyed children. Executives loved it, and Drayton’s work was soon featured on the sides of streetcars and in prominent magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post.

Drayton drew her angelic children for dozens of Campbell’s advertisements. Extremely childish at first, the Campbell’s kids eventually transitioned into more mature advocates for healthy eating and active lifestyles, and the characters remained a cornerstone of Campbell’s advertising for decades. Shortly after launching the campaign, Campbell’s soon recognized the merchandising potential of Drayton’s work. She was enlisted to draw dozens of postcards (including at least one that references women’s suffrage, but whether Drayton wrote the copy is unknown), and the drawings inspired a line of dolls that is still sought after by collectors today.

Drayton drew her angelic children for dozens of Campbell’s advertisements. Extremely childish at first, the Campbell’s kids eventually transitioned into more mature advocates for healthy eating and active lifestyles, and the characters remained a cornerstone of Campbell’s advertising for decades. Shortly after launching the campaign, Campbell’s soon recognized the merchandising potential of Drayton’s work. She was enlisted to draw dozens of postcards (including at least one that references women’s suffrage, but whether Drayton wrote the copy is unknown), and the drawings inspired a line of dolls that is still sought after by collectors today.

Hays lived in the shadow of her younger sister. She did draw a few of her own comic strips, including Jennie and Jack, also the Little Dog Jap, but she found more popularity as an artist of greeting cards, paper dolls, and children’s books.

Hays lived in the shadow of her younger sister. She did draw a few of her own comic strips, including Jennie and Jack, also the Little Dog Jap, but she found more popularity as an artist of greeting cards, paper dolls, and children’s books.

Saccharine by modern standards, Drayton and Hays’ style of art was a hit at the turn of the 20th century and heavily influenced the comics pages and commercial art for decades, into the 1930s and 1940s. Drayton and Hays were contemporaries with Rose O’Neill, whose incredibly popular Kewpies were conceived around 1909 and launched as toys in 1912 and also fueled the market for cartoons and merchandise featuring angelic, apple-faced children.

Saccharine by modern standards, Drayton and Hays’ style of art was a hit at the turn of the 20th century and heavily influenced the comics pages and commercial art for decades, into the 1930s and 1940s. Drayton and Hays were contemporaries with Rose O’Neill, whose incredibly popular Kewpies were conceived around 1909 and launched as toys in 1912 and also fueled the market for cartoons and merchandise featuring angelic, apple-faced children.

Much of this merchandise found a market outside of the United States, too, which likely influenced Japanese shojo (girls’) manga, including artist Matsumoto Katsuji, whose character Kurukuru Kurumi-chan reflected the lovable style employed by Drayton, Hays, and O’Neill. Launched in 1938 in a long-running manga, Kurumi-chan was also hugely popular in merchandise, including stickers, paper dolls, and toys. When asked about the influences on the character, Matsumoto couldn’t name a specific artist, but the inspiration of Drayton, Hays, and O’Neill is undeniable. As Ryan Holmberg writes for The Comics Journal, Matsumoto’s work bears the hallmarks of their artistic style:

“[Kurumi-chan] has many of the exaggerated neotenic features and sartorial accouterments that are associated with Japanese kawaii: an oversized head, low wide-set eyes, fat truncated limbs, adorable hand gestures, bell dress, a ribbon in the hair.

Hays passed away in 1925, and Drayton passed away in 1936, one year after starting her final comics venture, The Pussycat Princess. Even after passing, their work was reproduced and emulated for decades, putting an indelible mark on the market for cuteness worldwide.

Hays passed away in 1925, and Drayton passed away in 1936, one year after starting her final comics venture, The Pussycat Princess. Even after passing, their work was reproduced and emulated for decades, putting an indelible mark on the market for cuteness worldwide.

—by Betsy Gomez

Ramona Fradon

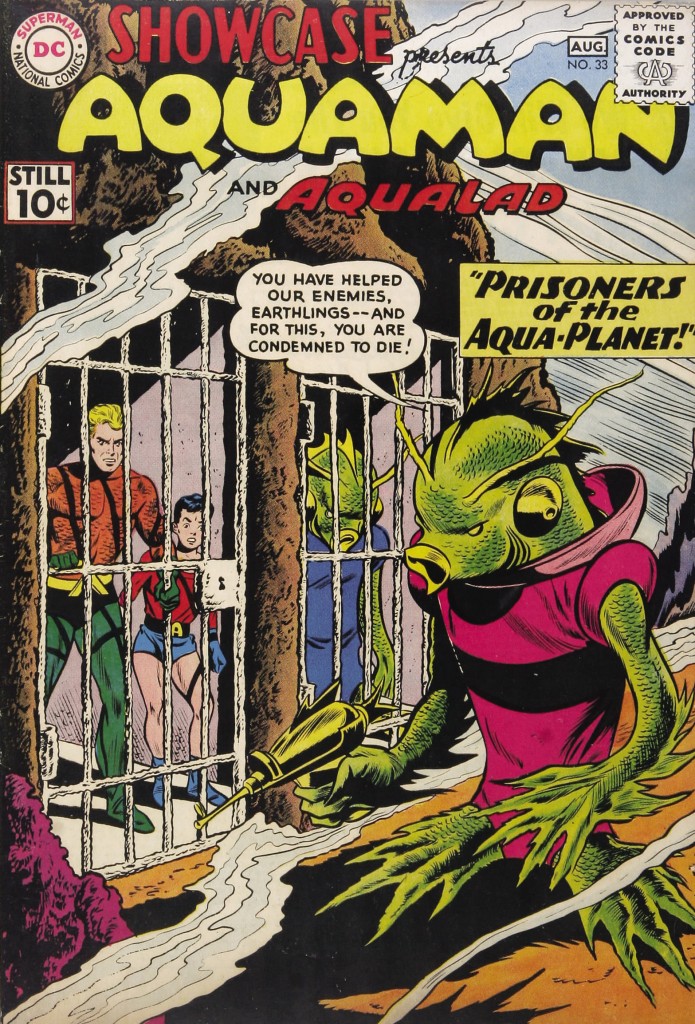

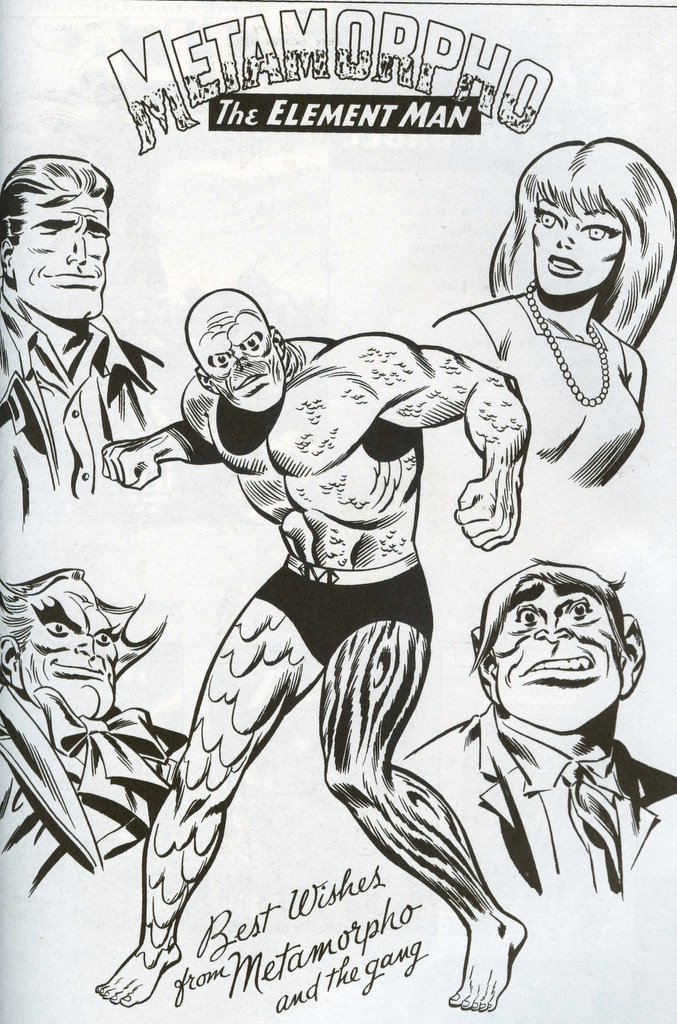

For a long stretch during the Silver Age of comics, Ramona Fradon was one of only two women artists working on superheroes. Over a long career drawing Aquaman, Metamorpho, Plastic Man, and the drastically different newspaper comic Brenda Starr, Reporter, among many others, she has earned praise and recognition from others in the industry, such as Jon Morris, who said that her character designs for Metamorpho “convey [the relationships between characters] in a manner so perfectly executed and nuanced that I honestly believe they’re the best-realized character designs in the entire genre of superhero comics.”

For a long stretch during the Silver Age of comics, Ramona Fradon was one of only two women artists working on superheroes. Over a long career drawing Aquaman, Metamorpho, Plastic Man, and the drastically different newspaper comic Brenda Starr, Reporter, among many others, she has earned praise and recognition from others in the industry, such as Jon Morris, who said that her character designs for Metamorpho “convey [the relationships between characters] in a manner so perfectly executed and nuanced that I honestly believe they’re the best-realized character designs in the entire genre of superhero comics.”

Fradon was born in 1926. Since her father was an artist, she said, “I grew up drawing, so it only seemed natural that I should become an artist.” She studied at the New York Art Students’ League and Parsons School of Design, graduating from the latter in 1950. Newly married to cartoonist Dana Fradon and “very poor,” she was encouraged by their friend George Ward, a comic book letterer, to try her hand at comics. In a 2000 interview with Katherine Keller, she recalled how she broke into the business: “I went out and bought a whole bunch of comic books and spent a couple of weeks reading them. I did a page of western action shots and took them up to DC and got a job.”

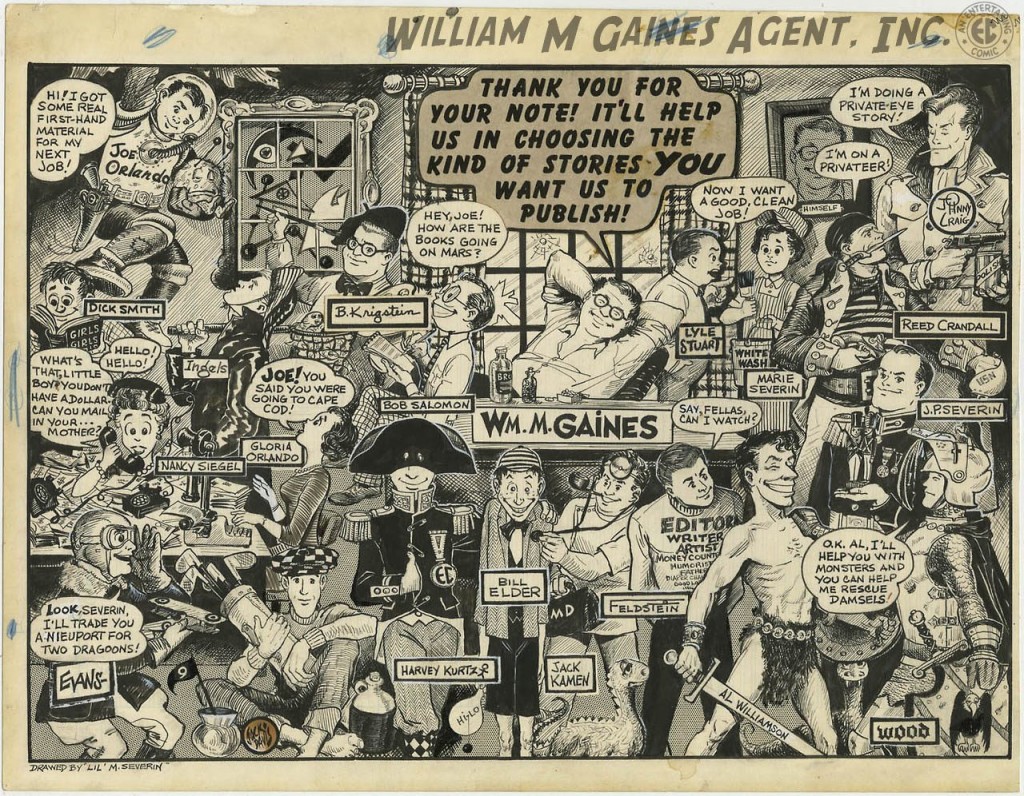

Her first work at DC was penciling and inking the Shining Knight story “Gadget Boom in Camelot” in Adventure Comics #165. A few issues later, the Shining Knight was replaced by Aquaman, and Fradon became one of the principal artists for that character for the next ten years. In 1960 she and writer Robert Bernstein co-created the Atlantean king’s sidekick Aqualad. In that era Fradon and Marie Severin at Marvel were the only women artists working on superhero comics, but Fradon later told Comic Book Resources’ Alex Dueben that their experiences were very different:

It’s funny that [Severin] was drawing Sub-Mariner while I was drawing Aquaman. People always used to ask me if I knew her, but I didn’t meet her until years later, at a convention. I didn’t work in a bullpen like Marie did so, aside from being uncomfortable with male fantasies and the violent subject matter, I never really experienced what it was like being the only woman working in a man’s world.

Fradon has always most enjoyed drawing characters with a humorous edge, as opposed to the more serious superheroes who she saw as “cardboard figures punching each other,” she told Keller. After a few years away from comics to raise her daughter, in 1965 she briefly returned to DC to co-create Metamorpho along with writer Bob Haney. After being exposed to a radioactive meteorite, Metamorpho can transform his body into different elements, combine those elements into compounds, transmute from a solid into a liquid or a gas, and shapeshift at will. Whereas with other characters, Fradon usually worked from a script and didn’t even know who wrote it, her collaboration with Haney was very different, she told Dueben: “That was a real meeting of minds. His goofy stories gave me ideas about how the characters should look and act, and my goofy pictures gave him new ideas. We laughed a lot while co-creating that crazy feature.”

Fradon then returned to childrearing full-time until the mid-1970s, when she returned to DC and worked on another quirky shapeshifting character, Plastic Man. She also penciled most issues of the Super Friends comic which ran from 1976 to 1981. In 1980 she made the leap to newspaper comics, taking over the illustration of Brenda Starr, Reporter from its original creator Dale Messick (previously profiled here).

As a condition of Fradon’s employment on the strip, the Tribune Media Services Syndicate made a stipulation that was unconventional to say the least: half of Messick’s annual pension was deducted from Fradon’s salary. Because Messick’s separation from the strip she created 40 years earlier was less than voluntary, Fradon said the older woman was “so angry at the syndicate that she vowed to live forever so that she could keep collecting that pension.” Messick was still going strong 15 years later when Fradon left the strip, and ultimately lived to 98 years of age.

Although Fradon found important differences between comic books and newspaper comics, telling Dueben it could be “somewhat discouraging to see all of the work you have done reduced to the size of a postage stamp,” she enjoyed depicting the life of a working mother like herself and especially loved hearing from women who had been fans of Brenda Starr over the years, including, she recalled, “one or two prominent women journalists [who] said that they were inspired by Brenda’s example to become reporters.”

In a 2014 tribute to Fradon’s work, Comics Alliance’s Patrick A. Reed described what makes it unique:

Fradon’s work is deceptively simple, with a number of defining elements – she’s a master of perspective, often placing the reader slightly below the horizon, looking up at the scene; her skill at depicting body language and facial expressions is unequaled; and her pages and covers are rendered with an expert sense of composition. Her design for Metamorpho is both memorable and totally unique, imbued with all the liquid, breezy, and down-to-earth qualities that an elemental hero could require. And in a time when women were almost non-existent in the industry, she established herself as a first-rate stylist and a one-of-a-kind creator.

At 89 years old, Fradon is still taking custom commissions and is a frequent guest on the convention circuit. At San Diego Comic Con 1999, she told Keller that “Ilove meeting fans. I love to sit here and watch these men who are in their forties now, they come and see my work and they get the sweetest smiles on their faces. It warms my heart.”

—by Maren Williams

Hilda Terry

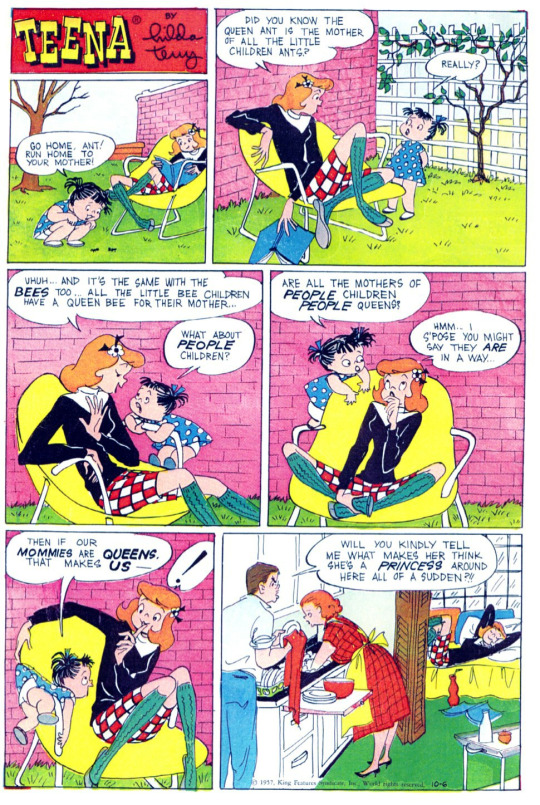

Today, we look at the work of a woman whose first comic strip came about at the direct request of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who was the first woman to join the exclusive boys club that was the National Cartoonists Society (holding the door open for other women behind her), and who helped pioneer the field of scoreboard animation.

Today, we look at the work of a woman whose first comic strip came about at the direct request of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who was the first woman to join the exclusive boys club that was the National Cartoonists Society (holding the door open for other women behind her), and who helped pioneer the field of scoreboard animation.

Hilda Terry began her career as a cartoonist for The Saturday Evening Post and other magazines. Her work caught the eye of William Randolph Hearst, who telegraphed subordinates, demanding that they “Get Hilda Terry” for his comics pages. In 1941, Terry’s first feature, It’s a Girl’s Life, ran for King Features. One of the very few comics (and for a long time, the only comic) to focus specifically on the interests of teen girls, the strip would eventually be retitled Teena and run in newspapers until 1964.

Terry’s husband, Gregory D’Alessio, nominated her to the National Cartoonists Society. At the time, the organization was exclusively male, and members hesitated to include women, presumably because “men wouldn’t be able to curse.” Terry didn’t hesitate to demand that the organization either rename itself or admit women. Her letter to NCS read:

Terry’s husband, Gregory D’Alessio, nominated her to the National Cartoonists Society. At the time, the organization was exclusively male, and members hesitated to include women, presumably because “men wouldn’t be able to curse.” Terry didn’t hesitate to demand that the organization either rename itself or admit women. Her letter to NCS read:

Gentlemen:

While we are, individually, in complete sympathy with your wish to convene unhampered by the presence of women, and while we would, individually, like to continue, as far as we are concerned, the indulgence of your masculine whim, we find that the cost of your stag privilege is stagnation for us, professionally. Therefore, we appeal to you, in all fairness, to consider that:

WHEREAS there is no information in the title to denote that it is exclusively a men’s organisation, and

WHEREAS a professional organisation that excludes women in this day and age is unheard of and unthought of, and

WHEREAS the public is therefore left to assume, where they are interested in any cartoonist of the female sex, that said cartoonist must be excluded from your exhibitions for other reasons damaging to the cartoonists professional prestige,

We most humbly request that you either alter your title to the National Men Cartoonists Society, or confine your activities to social and private functions, or discontinue, in effect, whatever rule or practice you have which bars otherwise qualified women cartoonists to membership for purely sexual reasons

Sincerely,

The Committee for Women Cartoonists

Hilda Terry, temporary chairwoman

Even though Terry met some resistance from a handful of NCS members, she had the support of majority, including Milton Caniff and Al Capp, so the boys club came to an end. Terry was admitted to NCS, and she shortly began nominating her female cartoonist friends for admission to the organization.

After a few years of freelance illustration, Terry left comics for baseball – more accurately the burgeoning field of scoreboard animation. The National Cartoonists Society awarded her its Best Animation Cartoonist award in 1979 for her giant animated portraits of baseball players.

After a few years of freelance illustration, Terry left comics for baseball – more accurately the burgeoning field of scoreboard animation. The National Cartoonists Society awarded her its Best Animation Cartoonist award in 1979 for her giant animated portraits of baseball players.

Terry effectively retired from animation and illustration in the 1980s, but she continued to teach at the Art Students League, where she herself learned art and met her husband, and she maintained an active online presence until her death in 2006 at the age of 92.

Terry effectively retired from animation and illustration in the 1980s, but she continued to teach at the Art Students League, where she herself learned art and met her husband, and she maintained an active online presence until her death in 2006 at the age of 92.

—by Betsy Gomez

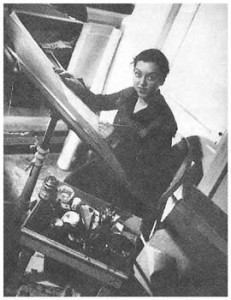

Marie Severin

Called the “First Lady of Comics,” award-winning artist and colorist Marie Severin has led one of the most interesting lives in the American comic book industry. Despite the myth that the industry was no place for a gal, her numerous achievements both in pre-code comics as well as in mainstream superhero fare proved time and time again that comics were in no way simply a boy’s club.

Called the “First Lady of Comics,” award-winning artist and colorist Marie Severin has led one of the most interesting lives in the American comic book industry. Despite the myth that the industry was no place for a gal, her numerous achievements both in pre-code comics as well as in mainstream superhero fare proved time and time again that comics were in no way simply a boy’s club.

In the 1950s, she fought alongside the EC group when the crusade against comics was in full force. In the 1960s, she would replace Steve Ditko and Bill Everett as the artist on Marvel’s Doctor Strange and would co-create Spider-Woman, costume and all. In the 1970s through her retirement, she took a stab at and conquered almost every genre of comic book she tackled, from horror to humor. To Editor Al Feldstein she was “the conscience of EC,” to Stan Lee “Mirthful Marie,” and today she stands as the inspiration for many myths and legends, representing one of the most acclaimed woman cartoonists in (mainstream) comics history.

Severin grew up in New York, the birthplace of the comics industry and lived with a family of artists. Her father was a trained artist from the Pratt Institute, her mother dabbled in illustration, and her brother John Severin was an EC artist. “I just took it for granted that’s what one did in this house, so I did,” noted the artist in an interview.

When Severin took on work at the EC offices in the late 1940s she was like a fish to water – the homegrown artist fit right in, never missing a beat in the frantic atmosphere of a publication house that prided themselves not only of producing the best comics, but embracing free expression. Although EC is often remembered for creating some of the most striking and gruesome horror scenes ever printed in four colors, the same freedom given to artists was extended to then colorist Severin, who is credited with using her personal color craft to bring a subdued, tasteful atmosphere to the gore and guts.

When Severin took on work at the EC offices in the late 1940s she was like a fish to water – the homegrown artist fit right in, never missing a beat in the frantic atmosphere of a publication house that prided themselves not only of producing the best comics, but embracing free expression. Although EC is often remembered for creating some of the most striking and gruesome horror scenes ever printed in four colors, the same freedom given to artists was extended to then colorist Severin, who is credited with using her personal color craft to bring a subdued, tasteful atmosphere to the gore and guts.

When the 1954 Senate Subcommittee Hearings all but forced the closure of EC and decimated the mainstream comics industry, Severin didn’t close shop… She went to Marvel. There, with Stan Lee’s blessing, she became a staff artist, working on Doctor Strange, Captain America, Sub-Mariner, Incredible Hulk, and Marvel’s satire magazine Not Brand Echh, to name a few. At Marvel, Severin was an inker, penciler, colorist, and art director. Her talent, positive attitude, and striking sense of humor saw her moving around the Marvel office just like any other creator. She wasn’t the demure, fragile female secretary that took notes and managed the important peoples’ schedules; she was one of the important people in the bullpen.

“Marie Severin, wide brown eyes hidden behind her glasses, dressed in what Robin Green described as ‘very Peck & Peck,’ held her own against both the boys’ club and the fans, all of whom she targeted in brilliant, wicked caricatures that were pinned up all around the [Marvel] office,” writes journalist Sean Howe.

“Marie Severin, wide brown eyes hidden behind her glasses, dressed in what Robin Green described as ‘very Peck & Peck,’ held her own against both the boys’ club and the fans, all of whom she targeted in brilliant, wicked caricatures that were pinned up all around the [Marvel] office,” writes journalist Sean Howe.

Severin was a powerhouse, and no one told her what she could and could not do. Unlike many female creators of the time, who found freedom of expression in the refuge of the Underground Comix Movement, Severin was a woman of the mainstream comics scene, and she dominated. Whether it be as the “conscience of EC,” “Mirthful Marie,” recipient of numerous awards, or member of the Eisner Hall of Fame, Severin truly is the First Lady of comics.

Severin was a powerhouse, and no one told her what she could and could not do. Unlike many female creators of the time, who found freedom of expression in the refuge of the Underground Comix Movement, Severin was a woman of the mainstream comics scene, and she dominated. Whether it be as the “conscience of EC,” “Mirthful Marie,” recipient of numerous awards, or member of the Eisner Hall of Fame, Severin truly is the First Lady of comics.

—by Caitlin McCabe

Lyn Chevli

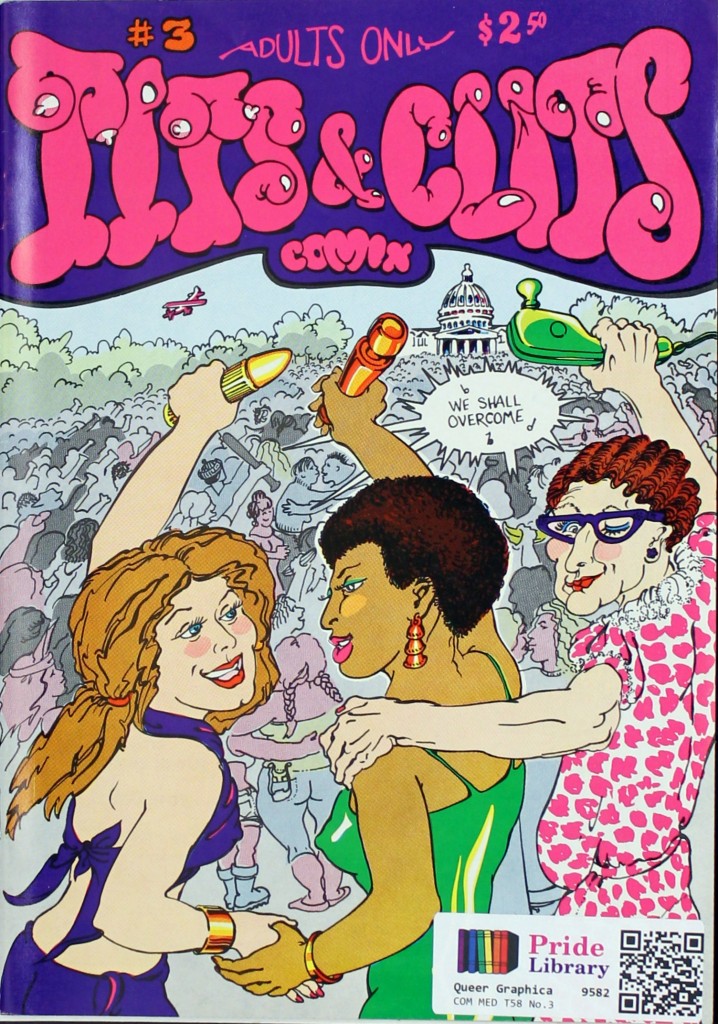

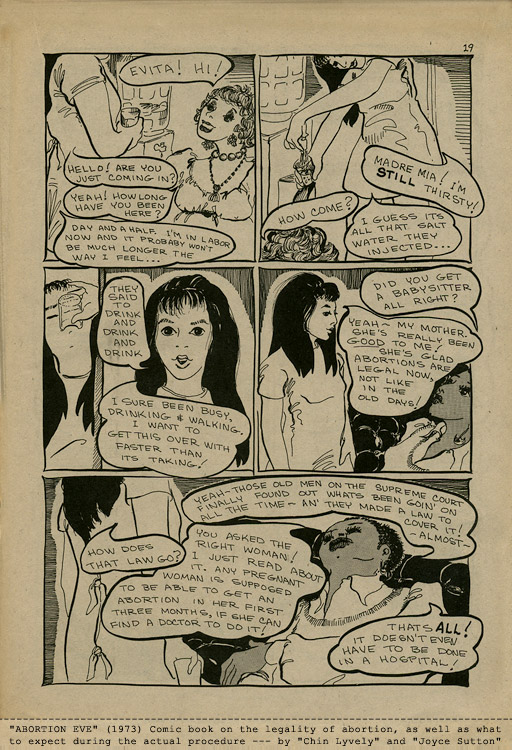

Entrepreneur and underground comix creator Lyn Chevli (a.k.a Lyn Chevli or “Chin Lyvely”) combated sexism in the underground and ignorance in the mainstream, helping create the seminal comix series Tits & Clits and reproductive rights one-shot Abortion Eve.

Entrepreneur and underground comix creator Lyn Chevli (a.k.a Lyn Chevli or “Chin Lyvely”) combated sexism in the underground and ignorance in the mainstream, helping create the seminal comix series Tits & Clits and reproductive rights one-shot Abortion Eve.

In a time when women’s health was something discussed behind closed doors, the co-founder of Nanny Goat Productions would use the comix medium to cast light on many important issues women faced in the 1970s. Whether it be the governmental regulation of women’s bodies — in 1973 the Supreme Court ruled after years of debate that abortions were legal, inciting huge political backlash that still continues to this day — or misconstrued ideas propagated by other all-male comics (and comix) that the feminine body was an object of sex, so talking about it was tantamount to pornographic taboo, Chevli sought to fight these detrimental ideas by teaming up with fellow women’s movement member Joyce Farmer and creating comix explicitly for women about women.

It must be noted that Chevli greatly admired the works of fellow underground artist like R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson, but their books didn’t speak to her as a woman. Instead of waiting for someone else to make the books she was interested in, though, the sculptor and bookstore owner took matters into her own hands by fighting for feminism in comix. Out of that initiative came Tits & Clits — an all-female anthology that ran from 1972 through 1987. “Hard at work at their drawing boards, [Chevli and Farmer] saw themselves as purveyors of feminist knowledge, putting women’s real-life experiences with sex and sexuality on paper,” notes Bitch Media.

Tits & Clits, much like Wimmen’s Comix, featured independent comix from women creators across the United States. To this day, it remains one of the Underground Comix Movement’s most memorable and important works, both for the doors it opened for women creators and for the conversations it started about women’s issues. Preceding Wimmen’s Comix to stores by 2 months, Chevli and Farmer’s idea to tell women’s stories through women’s eyes was a truly original and, shortly after its publication, a completely controversial concept.

Tits & Clits, much like Wimmen’s Comix, featured independent comix from women creators across the United States. To this day, it remains one of the Underground Comix Movement’s most memorable and important works, both for the doors it opened for women creators and for the conversations it started about women’s issues. Preceding Wimmen’s Comix to stores by 2 months, Chevli and Farmer’s idea to tell women’s stories through women’s eyes was a truly original and, shortly after its publication, a completely controversial concept.

Though Chevli and Farmer’s intentions were good, they found themselves on the wrong side of public perceptions about the landmark Supreme Court caseMiller v. California, the 1973 decision that established the test for determining whether material was obscene. Obscene materials are not protected by the First Amendment and as such open to legal prosecution. Sadly, the attention drawn by the court case as well as other political obstacles surrounding the regulation of women’s bodies, meant Chevli and Farmer’s work was openly being labeled pornography and obscene, proving a hindrance to distribution despite the fact that Chevli and Farmer’s work would have undoubtedly passed the Miller test for obscenity.

Though Chevli and Farmer’s intentions were good, they found themselves on the wrong side of public perceptions about the landmark Supreme Court caseMiller v. California, the 1973 decision that established the test for determining whether material was obscene. Obscene materials are not protected by the First Amendment and as such open to legal prosecution. Sadly, the attention drawn by the court case as well as other political obstacles surrounding the regulation of women’s bodies, meant Chevli and Farmer’s work was openly being labeled pornography and obscene, proving a hindrance to distribution despite the fact that Chevli and Farmer’s work would have undoubtedly passed the Miller test for obscenity.

In 1973, the new owners of Chevli’s old bookstore, Farenheit 451, were arrested for distributing pornographic materials, demonstrating just how close the scrutiny impacted Chevli and her work. “The decision to be vulgar rather than high class arose out of sheer ignorance,” said Chevli in an interview withCultural Correspondence:

Neither of us was much of a comics fan, but at the time we started I owned a bookstore, sold Ugs [undergrounds], and was impressed by their honesty but loathed their macho depiction of sex. Our work, originally, was a reaction to the glut of testosterone in comics […] As most of us know, sex is a very political business. All we want to do is equalize that by telling our side […] Our original commitment was to concentrate of female sexuality, and our title indicates that.

The 1970s were full on “sexual anarchy,” but instead of sitting on the sidelines while yet again another war was waged against women, Chevli wanted to make sure that women didn’t become the victims of misinformation and that they had a place to talk about themselves and their bodies — despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that many had labeled such conversations “pornographic” and “obscene.”

—by Caitlin McCabe

Joyce Farmer

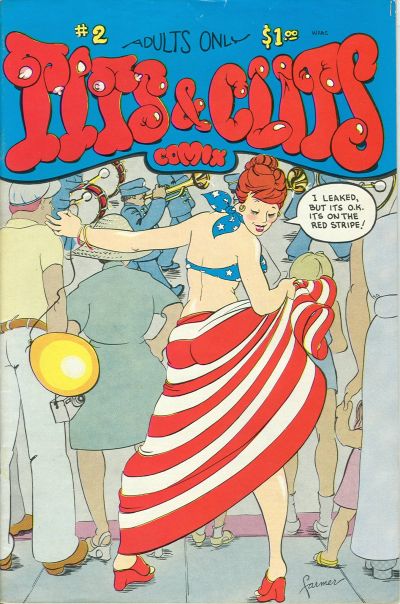

Joyce Farmer was born in 1938 and grew up in South Los Angeles. Just out of high school in the 1950s she took classes in Advertising Design at the Art Center School, but left after two semesters. Starting in the early 1970s, Farmer and her publishing partner Lyn Chevli (previously profiled here) were involved in two groundbreaking underground comix that countered the male-dominated field.

Joyce Farmer was born in 1938 and grew up in South Los Angeles. Just out of high school in the 1950s she took classes in Advertising Design at the Art Center School, but left after two semesters. Starting in the early 1970s, Farmer and her publishing partner Lyn Chevli (previously profiled here) were involved in two groundbreaking underground comix that countered the male-dominated field.

First published in 1972, Tits & Clits Comix (also known in the New York Times as “a notorious series about women’s sexuality whose title can’t be reproduced here”) was a response to other underground titles like Zap Comix, which Farmer described as “really brutal against women.” Tits & Clits, on the other hand, was from the perspective of “women and how they actually look at sex: they’re worried about birth control, they’re worried about menstrual factors. There’s many factors to sex that men don’t pay any attention to, and women have to pay exquisite attention to, or we pay heavily.” Despite a 1973 pornography investigation by the Orange County district attorney, Farmer and Chevli continued the irregular series until 1987.

Also in 1973, shortly after the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision guaranteed women the right to abortion, Farmer and Chevli created the one-shot comic Abortion Eve. Both were then working as pregnancy counselors and wanted to help dispel abortion myths and provide matter-of-fact information about the procedure. The book’s cover promises “a discussion about the legality of abortion, what to expect during an abortion, head trips—before and after, and much more….” Inside is the story of five women of different ages, races, and backgrounds who meet in the waiting room of an abortion clinic and slowly realize that their own opinions about why other women choose abortion are often wrong–and above all, irrelevant.

Also in 1973, shortly after the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision guaranteed women the right to abortion, Farmer and Chevli created the one-shot comic Abortion Eve. Both were then working as pregnancy counselors and wanted to help dispel abortion myths and provide matter-of-fact information about the procedure. The book’s cover promises “a discussion about the legality of abortion, what to expect during an abortion, head trips—before and after, and much more….” Inside is the story of five women of different ages, races, and backgrounds who meet in the waiting room of an abortion clinic and slowly realize that their own opinions about why other women choose abortion are often wrong–and above all, irrelevant.

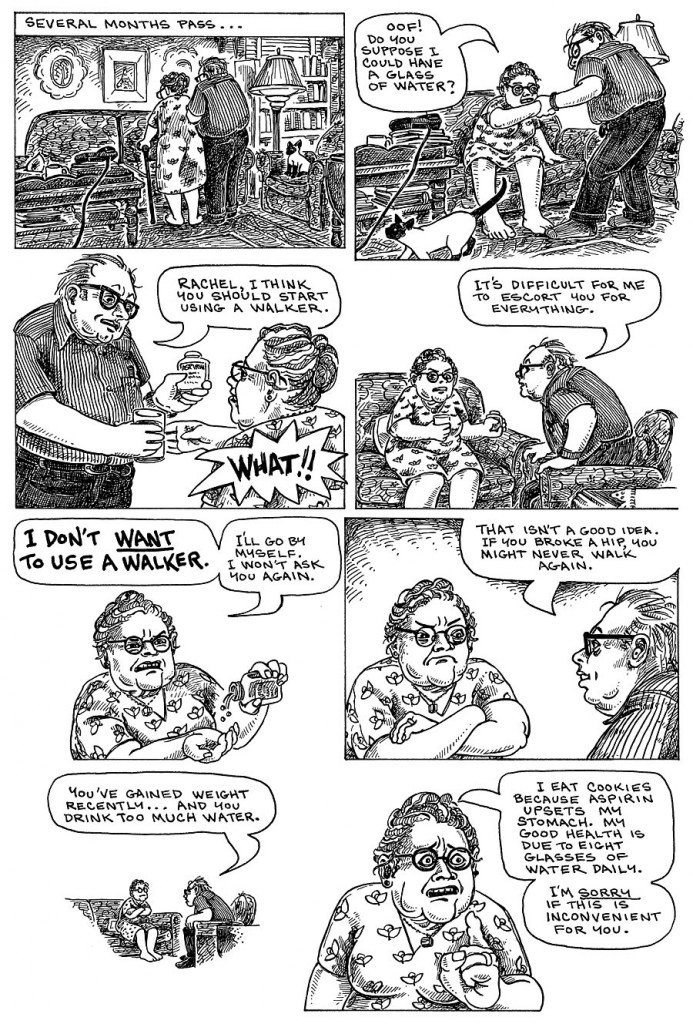

In the post-Tits & Clits years of the late 1980s and early ‘90s, Farmer took an extended break from comics as she struggled to make ends meet financially, working for a time as a bail bond agent. Meanwhile, her life was also consumed with caring for her aging father and stepmother, her own mother having died when Farmer was very young. A few years after they died of lung cancer and Alzheimer’s, she realized that the aging process and death were topics ripe for exploration in the graphic novel format and set about creating her tour de force Special Exits.

In the post-Tits & Clits years of the late 1980s and early ‘90s, Farmer took an extended break from comics as she struggled to make ends meet financially, working for a time as a bail bond agent. Meanwhile, her life was also consumed with caring for her aging father and stepmother, her own mother having died when Farmer was very young. A few years after they died of lung cancer and Alzheimer’s, she realized that the aging process and death were topics ripe for exploration in the graphic novel format and set about creating her tour de force Special Exits.

Farmer painstakingly drew, lettered, and inked all 200 pages of Special Exits by hand, a process that wound up taking 13 years. While working on the book she developed macular degeneration and had surgery for the condition just after she finished the penciling, completing the rest of the project while wearing an eye patch. The result is a meticulously detailed and brutally honest memoir that does not shy away from the ugly facts of death such as dementia, loss of dignity, and mistreatment by medical personnel. While the book was in progress, Farmer sent pages to Robert Crumb for feedback. His glowing assessment took pride of place on the cover when it was finally published by Fantagraphics in 2010: “One of the best long-narrative comics I’ve ever read, right up there with Maus… I actually found myself moved to tears.”

Farmer painstakingly drew, lettered, and inked all 200 pages of Special Exits by hand, a process that wound up taking 13 years. While working on the book she developed macular degeneration and had surgery for the condition just after she finished the penciling, completing the rest of the project while wearing an eye patch. The result is a meticulously detailed and brutally honest memoir that does not shy away from the ugly facts of death such as dementia, loss of dignity, and mistreatment by medical personnel. While the book was in progress, Farmer sent pages to Robert Crumb for feedback. His glowing assessment took pride of place on the cover when it was finally published by Fantagraphics in 2010: “One of the best long-narrative comics I’ve ever read, right up there with Maus… I actually found myself moved to tears.”

After Special Exits was published to universal critical praise, Farmer was asked in an interview with Comic Book Resources’ Alex Dueben what she planned to do next. After so long away from the scene, perhaps a collected edition of Tits & Clits was in order? She admitted she wasn’t sure, since the creation of Special Exits was largely a therapeutic exercise and its success was a surprise:

I haven’t been in the comics community for years. Part of the reason why is that ‘Tits and Clits’ was so poorly misunderstood when we did it. I got enough negative flack from enough people that I just went on with my life and didn’t worry about it. If something happens now it’ll be nice.

In any case, if she did choose to throw herself into another sequential art project, Farmer was sure that it would break more taboos–not out of any deliberate effort to be edgy, but because she simply can’t imagine any other way of making art. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times’ Deborah Vankin, she relishedthis role: “I can be wild. I’m always doing something. And I don’t care if it’s radical or not. That’s part of being an artist. You have to have an edge, or there’s no point.”

—by Maren Williams

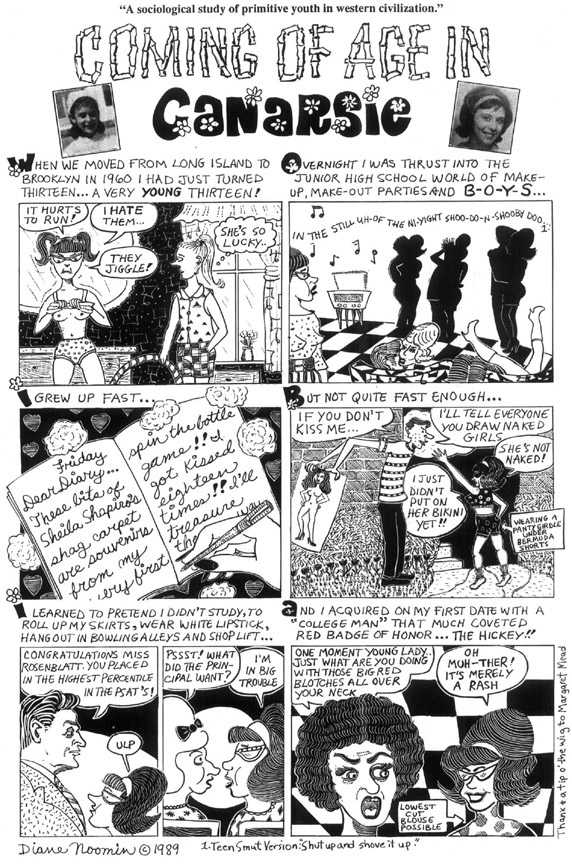

Diane Noomin

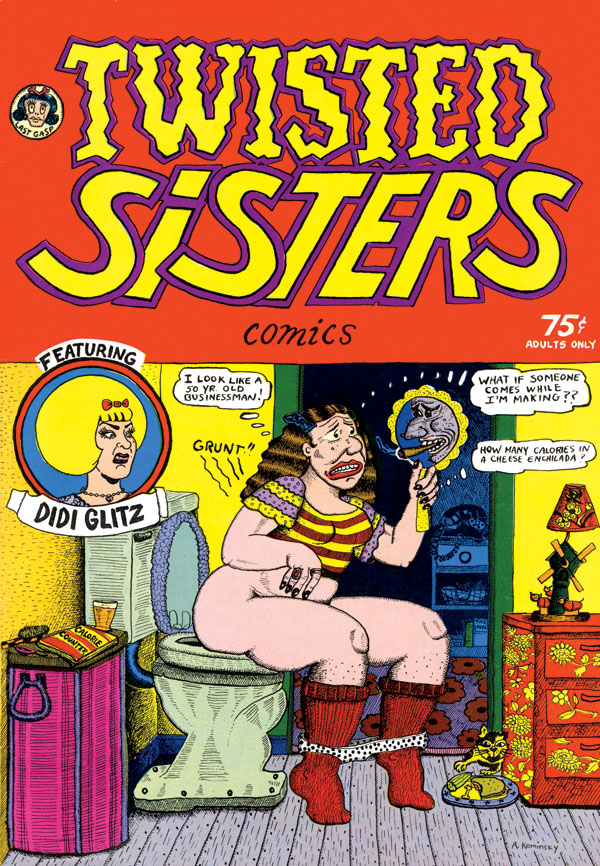

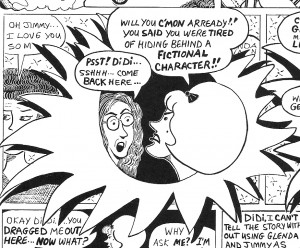

An original contributor to the underground anthology Wimmen’s Comix, co-founder of the equally important Twisted Sisters comics, and creator of the boisterous DiDi Glitz, Dianne Noomin was a true renegade of the underground.

An original contributor to the underground anthology Wimmen’s Comix, co-founder of the equally important Twisted Sisters comics, and creator of the boisterous DiDi Glitz, Dianne Noomin was a true renegade of the underground.

Unlike some female comix creators of the 1970s, who were paving the way for women through the creation of all-female comic collectives, Noomin blended her talents and told her stories in the same books as R. Crumb, Bill Griffith, and Art Spiegelman. For Noomin, the possibility and power of the medium, especially for women, extended past a starkly defined male/female divide, and it is in this space that she conquered and explicitly proved the boys’ club was no “men-only” club.

“There was a very strong need for feminism across the board in this country,” said Noomin in an interview with The Comics Journal:

“There was a very strong need for feminism across the board in this country,” said Noomin in an interview with The Comics Journal:

When I was looking for work after high school, there were jobs called girl Fridays, and there were separate want ads for men and women… I think a lot of younger women don’t have to think about it today, so that earlier stuff can come across as strident, but that wasn’t my interest in doing comics. My interest was in personal stories.

Whether it be Weirdo, Young Lust, Arcade, or Wimmen’s Comix—all books Noomin contributed to—the important thing for the creator was the story. “I could do comics about anything,” notes Noomin. If she couldn’t find the right space to tell her own story, Noomin created it, and that was how Twisted Sisters was born in 1976.

When Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Noomin felt that the “women’s collective” mentality was becoming more about politics—“a hot-bed of bickering and power plays”—and less about telling women’s stories, they got in touch with publisher Last Gasp and “just created our own comic,” recounts Noomin. “We went to Last Gasp and asked Ron Turner if he would do Twisted Sisters. It was just Aline and me. She did the front cover, I did the back cover, and we each did a story as long as we wanted and that was it.”

For Noomin and Kominsky-Crumb, “we preferred to have our flaws and show them”:

For Noomin and Kominsky-Crumb, “we preferred to have our flaws and show them”:

Basically, we felt that our type of humor was self-deprecating and ironic and that what they were pushing for in the name of feminism and political correctness was a sort of self-aggrandizing and idealistic view of women as a super-race.

Twisted Sisters—and really all of Noomi’s women characters—were women who were, as Nicole Rudrick describes DiDi Glitz, “equal parts sex, anxiety, domesticity, and rebellion—by turns a garish, boozy mess and a modern, self-affirming woman.”

Didi Glitz would become Noomin’s comic doppelganger and a vehicle to tell stories and share experiences that were more personal and autobiographical. Noomin’s subject matter may have been “the woman,” but her storytelling was about showing her raw, human sides. The work that Noomin did early in her career and still today, illustrating the adventures of DiDi. would inspire and set the groundwork for many of the graphic memoirs that are prevalent in the industry now.

Didi Glitz would become Noomin’s comic doppelganger and a vehicle to tell stories and share experiences that were more personal and autobiographical. Noomin’s subject matter may have been “the woman,” but her storytelling was about showing her raw, human sides. The work that Noomin did early in her career and still today, illustrating the adventures of DiDi. would inspire and set the groundwork for many of the graphic memoirs that are prevalent in the industry now.

–by Caitlin McCabe

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.