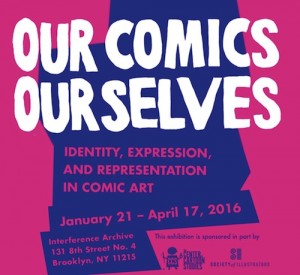

Earlier this year, CBLDF Executive Director Charles Brownstein toured the exhibit Our Comics, Ourselves: Identity, Expression, and Representation in Comic Art at Brooklyn’s Interference Archive. The physical exhibit packed up in April, but it lives on as a Tumblr blog with a series of guest curators–and this week it’s Brownstein’s turn!

Earlier this year, CBLDF Executive Director Charles Brownstein toured the exhibit Our Comics, Ourselves: Identity, Expression, and Representation in Comic Art at Brooklyn’s Interference Archive. The physical exhibit packed up in April, but it lives on as a Tumblr blog with a series of guest curators–and this week it’s Brownstein’s turn!

In his posts this week, Brownstein has highlighted our recent list of LGBTQ comics creators, Caitlin McCabe’s historical overview of how the Comics Code helped set the stage for LGBTQ comics emerging from the underground comix movement, Brownstein’s own profile of Dori Seda that will appear in the upcoming She Changed Comics, and Atena Farghadani’s bold return to cartooning just weeks after she was released from prison in Iran.

Expanding on the way that freedom of expression is too often taken for granted in the United States, he also featured a Beirut symposium organized by the Lebanese comics collective Samandal in which he participated this past March. The international panel of participants naturally brought different perspectives on freedom of expression in comics, he said:

I started, examining censorship as an exercise of social control by government through the prism of comics censorship cases in the United States. I fundamentally advocated that more speech is always preferable than less speech; that freedom of expression guarantees the ability to compete in the marketplace of ideas, but does not inoculate from criticism; and that violence and political suppression must always be shunned as methods of combating speech. But my point of view comes from the privilege of living in the United States, where the First Amendment guarantees our right to free expression.

Dr. Irina Chiaburu, an expert in Soviet animation during the late Soviet period, examined censorship as a fact of state reality and suggested a framework through which artists seek to “outsmart” censorship. It’s easy for those of us in the United States to take for granted intellectual freedom, however it is not a basic and established right everywhere. In parts of the world where state censorship is a given, there are more fundamental arguments concerning intellectual freedom still raging. From my point of view, this should make us more deeply appreciative and protective of the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment.

You can listen to the full two-hour symposium here!

In another post, Brownstein examined the 1953 war story “In Gratitude” from EC Comics’ Shock SuspenStories, as well as the well-reasoned discussion between adults, many of them military service members, that ensued through letters columns in subsequent issues. In contrast to the popular image of comics at the time, the story by Al Feldstein and Wallace Wood about a Black soldier who died saving his comrades-in-arms is “a meditation on heroism, sacrifice, bigotry, and race,” says Brownstein. But perhaps even more remarkable are the letters that followed it:

It’s far more than kids that were reading these comics, if kids actually read them at all. I’ve also presented a letters page from Shock Suspenstories #13, with an outraged letter from an active duty serviceman who took umbrage with this story, and a flood of responses to that letter that were published in Shock Suspenstories #16.

Gaines died before I got into comics, and Feldstein I met only briefly. I wish I could have asked them why the industry conceded that comics were being sold predominantly to kids during the Senate Hearings of 1954, when their letters pages were proof positive that their comics were a platform for serious adult debate concerning one of the key social justice issues of the time.

Check out Brownstein’s guest posts and the entire Our Comics, Ourselves blog here!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!