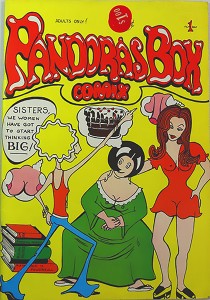

Joyce Farmer walked into Fahrenheit 451 Bookstore & Art Gallery the morning of December 4, 1973, feeling confident. She carried with her several copies of her new underground comic book Pandora’s Box, fresh from the printer. Like Joyce’s earlier comics, this one was best described as “blatantly outrageous.” She and Lyn Chevli had outdone themselves this time.

Having already sold a number of comics in the Bay Area, Joyce didn’t anticipate any problems in her hometown. True, Laguna Beach, California was not as good a market as, say, San Francisco, but the owners of Fahrenheit 451 could usually be counted on for a small sale. After all, they knew Lyn. Lyn and her then-husband, Dennis Madison, had founded Fahrenheit 451 back in 1968. Gordon and Evelyn Wilson had bought the bookstore from Lyn back in the spring of 1972, right before she and Joyce had embarked on their career in comics.

That day, though, there was to be no sale. Instead, a somber Evelyn told Joyce that Fahrenheit 451 couldn’t carry her new book. The day before, she and her husband had been arrested for selling underground comic books. Lyn and Joyce should take care, said Evie. They were likely to be next.

***

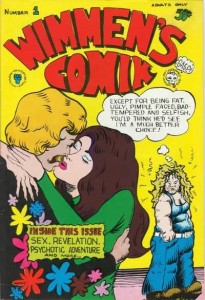

Wimmen’s Comix #1, published November 1972. At the time of the bust, three issues of the series were in print. Cover art by Patricia Moodian.

Five days before the Wilsons’ arrest, Laguna Beach Police detective Anthony Smith had stopped by Fahrenheit 451 on unrelated business. What business he may have had there remains unknown; the store, which specialized in countercultural texts like The Whole Earth Catalogue and Jonathan Livingston Seagull, wasn’t necessarily a popular destination for police officers. Perusing Fahrenheit 451’s eclectic wares, the store’s collection of underground comics caught Detective Smith’s eye.

The Wilsons hadn’t given much thought to the comic books, which they had inherited along with the rest of their stock. They sold one, maybe two, underground comic books a day, as they told a reporter later. Neither considered themselves a fan, since underground comix—graphic, satirical stories full of violence, sex, drugs, and occasional political commentary, spelled with an “x” to designate their alternative status—were not what they would call literature, but neither was overly concerned about them, either.

Detective Tony Smith, though, was quite perturbed by the comix. They were, as he told the Daily Pilot, “‘filthy and dirty’—some involving the dismemberment of human bodies and sexual acts.” He picked up four of the comic books—Wimmen’s Comix, Greaser, Zap Comix No. 5, and El Perfecto, as the Daily Pilot later reported—and took them to the register, making sure to get a receipt for his purchase.

Smith then headed to the district attorney’s office. He presented the underground comix to a deputy district attorney, asking for a legal opinion as to whether or not they would be considered obscenity. The office found three out of four of the comics to be “without redeeming social value,” as reported in the Daily Pilot. The D.A. issued a court warrant for the Wilsons on the charges of selling and distributing pornography, a misdemeanor crime.

The following Monday, December 3, Detective Smith went back to Fahrenheit 451, this time bringing along his fellow officer Bruce Briggs. Seizing a copy of Zap Comix No. 3, the two placed Evelyn Wilson under arrest. After searching the Wilsons’ small apartment above the bookstore, the police escorted Evie to the police station, where they took her fingerprints and mug shots, as they did for Gordon when he arrived. The Wilsons paid their $500 bail—$250 each, the couple’s Christmas money—and were released.

Outraged by what he considered to be an act of overt censorship, Gordon marched straight to the offices of the Laguna Beach Daily Pilot, where he was ushered to the desk of Jack Chappell. After listening sympathetically to Gordon’s story, the young reporter made the Wilsons front page news.

“LAGUNANS HELD ON SMUT RAP,” blared Tuesday’s Daily Pilot. “COMICS PROMPT TWO ARRESTS.”

***

Joyce hadn’t seen that morning’s headlines before she arrived at Fahrenheit 451, but she understood the significance of the Wilsons’ arrest immediately. Leaving Fahrenheit 451, Joyce headed to Lyn’s apartment to tell her what had happened.

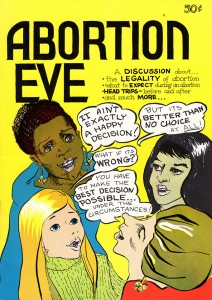

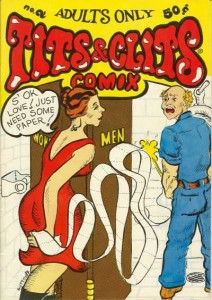

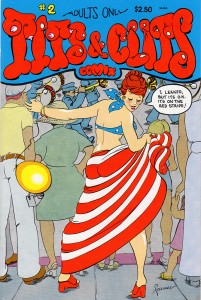

Over lukewarm cups of coffee, the two women quickly arrived at the conclusion that they, not the Wilsons, were the real targets of the bust. The police must have thought that Lyn still owned Fahrenheit 451 and that busting the bookstore would lead them directly to Lyn and Joyce’s underground comics business. Under the banner of Nanny Goat Productions, the duo had been producing and publishing raunchy comics since 1972. Their three comic books—Tits & Clits, Abortion Eve, and Pandora’s Box—explored the vagaries of vaginas from menstrual blood to yeast infections.

Lyn and Joyce saw themselves as revolutionaries challenging society’s views about female sexuality. “As most of us know, sex is a very political business, “said Lyn in an interview with Cultural Correspondence. “All we want to do is equalize that by telling our side.”

That she and Joyce were, in many ways, the kind of women one would least expect capable of such provocation simply added to their subversive fun.

“I… suspect that it blows a few minds when readers discover that Joyce and I are 33 and 40 years old, the mothers of teen aged kids, pillars of society, attractive, charming, and heterosexual,” wrote Lyn in a 1972 letter. “We are also responsible citizens and produced this disgusting work from a sense of frustration and a deep philosophical base.”

While Lyn and Joyce did not consider their work to be obscene, they knew well that other people did. Two months before the Wilsons’ arrest, in a letter to the editor of Viva Magazine, Lyn noted that their first comic, Tits & Clits (1972), “has been described as pornography and perhaps it is, but we prefer to think of it as an iconoclastic look at female sexuality.”

Despite these noble intentions, many of Lyn and Joyce’s friends and colleagues were shocked and horrified by the explicitness of their comics. Even fans of the comics seemed to miss the underlying philosophy. A writer for the sex magazine Screw, for instance, admiringly called Tits & Clits “altogether a new thing: female smut. God knows what they’ll come up with next, the hussies.”

Given Lyn’s connection to Fahrenheit 451, it could not be a coincidence, the women of Nanny Goat speculated, that the police chose to bust the Wilsons. Plenty of other stores in the area sold underground comics. Indeed, the Daily Pilot reported in the days following the Wilsons’ arrest that Zap Comix were still being sold elsewhere in town. As Lyn later wrote in her unpublished memoir:

Somehow or other information reached the powers-that-be that a woman in Laguna not only owned a bookstore that sold this filth [underground comics], but that she actually published it herself. Whether they knew I wrote it too I don’t know, but I guess they decided it would make a perfect case. After all, everyone knows that porn princesses, like women drunks, are dirtier and more lowdown than porn princes.

No Nanny Goat titles were mentioned in the newspaper’s accounts of the bust, but Lyn and Joyce took this omission as further proof for their theory.

“Our comic T&C was declared obscene by the DA but so far has missed all publicity, either because they aren’t smart enough to find us (‘they’ being the Local Police Dept.) or because they are working on getting us and don’t want to talk,” wrote Joyce to her friend Clay Geerdes on December 6. “Notice that the newspaper can’t even print our title!”

“If you think all of this is paranoid, please understand otherwise,” she continued. The local police want to get the ‘publishers and writers’ of comix… and we know they have copies of our comics.”

In fact, Deputy District Attorney John Anderson had told the Daily Pilot on December 5 that his office was doing all it could “to track down these printers and publishers and writers of this kind of book.” While the Fahrenheit 451 case was the first of its kind in Orange County, bookstores across California, from Berkeley to Encino, had been busted for selling underground comixstarting in the late 1960s. Anderson added that it was “‘kind of too bad’ that little people like the Wilsons got swept up in the smut net … [but] ‘that’s the quickest way to get to publishers.'”

Publishers, in this case, seemed to mean Joyce and Lyn. Nanny Goat Productions was the sole producer and distributor of underground comics in Laguna Beach, as far as Lyn and Joyce knew. If the duo were charged with selling and distributing pornography, the charge levied against the Wilsons, they would face up to six months in jail and a $1,000 fine—not to mention lawyers’ fees, trial fees, and so on. Neither woman could afford the legal battle.

Worried, the pair immediately sought legal advice from a lawyer friend, who told them to get rid of anything and everything linking them to Nanny Goat Productions, particularly their comics.

Lyn and Joyce made plans to meet up later to move their comics under the cover of night. In the meantime, they warned their children not to answer the door to avoid search warrants. Then they began gathering up everything they had that linked them to Nanny Goat Productions. Lyn later wrote:

We took posters, photographs, comic book covers and party invitations down from our walls, weeded out personal and business correspondence and had copies made of strategic papers which might be needed for dozens of reasons, including a trial … It was a time-consuming nuisance which made us feel discouraged. We asked ourselves if this really was the land of free speech. How could we be such a terrible threat to society? And if we were, was such a fragile society worth protecting?

That evening, Joyce and Lyn toted box after box of comics from Joyce’s art studio and Lyn’s apartment to the truck they had borrowed. Around 50 friends and neighbors offered their assistance, their spare closets, and their garages. From 8 P.M. until 2. A.M., the women of Nanny Goat spread their smut all over town before collapsing, exhausted.

***

The next morning, reporter Jack Chappell of the Daily Pilot confirmed what Lyn and Joyce suspected. “Laguna Bookstore Owners Pawns in Smut Campaign?” read the front page on Wednesday, December 6. Though Orange County Deputy D.A. Oretta Sears refused to call the Wilsons’ arrest a “test case” for establishing underground comics as obscene, Chappell noted that “a successful prosecution could set a county precedent.” The Wilsons’ arrest wasn’t coincidental, according to Chappell. Rather, armed with new court rulings regarding California’s obscenity laws, legal authorities across the county were moving aggressively against pornography.

Orange County wasn’t alone in testing out the limits of obscenity law. At the time, legal authorities all across the United States were newly invigorated to crack down on “hard core pornography” after the Supreme Court’s decision in Miller v. California in June of 1973. In fact, the Miller case had originated in Orange County; Deputy D.A. Oretta Sears had acted as one of the State’s prosecutors. (It was later revealed by the Los Angeles Times that Detective Smith had visited Fahrenheit 451 that fateful day to look for “another publication” on behalf of the Orange Police Department.)

Previously, in Roth v. United States (1957), the Supreme Court had ruled that obscenity—defined by its lack of “even the slightest redeeming social importance”—was not protected by the First Amendment. Anyone who produced, possessed, published, spread, showed, or sold obscenity could rightly prosecuted under relevant state and federal laws. If the average American, standing in for the current opinion of her community, found that any given material lacked all literary, artistic, or scientific value and appealed to a morbid, excessive interest in sex (otherwise known as “prurient interest”), then she could rightly deem it obscene.

Miller changed obscenity law by instituting a three-pronged test for obscenity, which came to be known as the “Miller test”:

a) whether “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest,

b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law, and

c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value…

The Court further clarified that the “community standards” need not be national ones, but rather those that prevailed in the community where the case originated. The Miller decision caused an explosion of cases like that of the Wilsons, all seeking to test the constraints and opportunities of “local standards” for pornography.

Lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union agreed to take the Wilsons’ case. As Joyce told her friend, underground comix fan Clay Geerdes, on Thursday, December 6,

Things are looking up! The Wilsons are being defended by a crackerjack ACLU team, every writer in town is on the bandwagon — Zaps are priceless & unavailable at the moment — a Mob is picketing town the day after tomorrow & I aint been busted yet! … I just came from a meeting attended by about 60 of the above described people & the whole thing looks very well organized.

At the meeting Joyce attended, the Wilsons and their supporters mapped out their plans for a protest rally and petition drive to be held Sunday, December 9. Gordon Wilson called for a special city council meeting to discuss what the “local community standards” for Laguna Beach truly were,despite being advised that the city council did not, in fact, have the legal authority to define “community standards”–that was a matter for the courts.

“The latest news (12/7/73, 10:00 p.m.) is they were originally looking for T&C specifically,” wrote Joyce to Clay Geerdes on the same date. “It seems, for some reason, they have to bust a retailer in Laguna Beach for selling T&C to get to me. Why they can’t just come here, I don’t know. Wish they would. The suspense is giving me headaches.”

Joyce and Lyn did not attend the protest rally for the Wilsons on Sunday, December 9—they were still trying to lay low—but around 30 people did. They carried signs like “No Censorship for Laguna” and “Make a Scene about What’s Obscene” and circulated petitions asking the City Council to “enact ordinances ‘protecting the people of our community against the outside attempts to censor the reading material of its adult members.'”

“One man carried a blank sign,” reported the Daily Pilot. “He said it had been censored.”

The women of Nanny Goat watched the ruckus unfold with curiosity and trepidation. Lyn wrote in a December 12 letter to fellow underground publisher Don Baumgart, “We are really the ones they are after, but the town is in an uproar so maybe they don’t dare just now.”

“Rumors flying, we can’t tell whether to feel safe or paranoid,” wrote Joyce a few days later. “One day we hear that the District Attorney’s office wants us as pornographic publishers and distributors, the next we hear they have investigated us and decided we are not only small beer but that our comic may have redeeming social importance.”

Paranoia was warranted. Lawyers advised the women of Nanny Goat that it was possible that they could be charged with a felony for transporting obscenities interstate. Joyce feared that she might lose her home, which she owned, if they were ever arrested.

Despite the support they received from their fellow artists and writers in Laguna Beach, Lyn and Joyce felt not only frightened, but deeply misunderstood. As Lyn wrote later,

[As] I sat and listened [during a meeting for the Wilsons], I realized that none of the people there had the faintest idea of what we were trying to do. On a philosophical or sociological level they were untouched by our work, immune to our rationale, and evidently embarrassed by the vehicle through which we chose to speak … They insisted upon speaking of our books as ‘your pornography,’ without realizing that this was insulting us. In fact, most of the people in the room had never read our work, didn’t want to read our work, and probably never would read our work.

Being hailed as celebrities in the grocery store and at the post office brought some comfort, but not enough to counterbalance such a grievous misreading of their comics.

Going against the advice of their lawyer, Lyn and Joyce agreed to an interview with Daily Pilot reporter Jack Chappell, which was published on December 26. Using the pseudonyms Jan and Lyvely, they told him that they expected to be arrested any day, but that they stood behind their work as “a valid expression of women’s viewpoints.”

“I believe this more than I’ve every [sic] believed in anything in my life,” Lyvely declared.

“I feel like I’m living in Nazi Germany. But you can’t push people back after they’ve experienced sexual freedom, legal abortion and no censorship. You can’t push them back… We characterize ourselves as being feminist-humorists. We are the first feminist-humorists of the United States – absolutely the first, and we know this,” [said Jan].

In their interview, the women of Nanny Goat stressed that they had never considered that they might get in trouble for their comics. Yes, their work broke taboos—but that was what underground comix were all about. They in no way considered what they did to be a threat to society; Tits & Clits, Pandora’s Box, and Abortion Eve were all about liberation, specifically women’s liberation.

As the days passed and nothing happened, Lyn and Joyce began to relax, though not completely. In early January of 1974, after shuffling comics from house to house for several weeks, they decided to move their entire inventory out of Laguna Beach. That way, if they did get busted, none of their comics would be in the county.

One of their distributors, Irv O’Connell, offered the duo warehouse space in Los Angeles. Lyn and Joyce rented a U-Haul and loaded it up with boxes of books. Driving extremely carefully, in order to avoid being pulled over, the women suspected they were nonetheless being followed. Lyn wrote,

I caught a glimpse in the rear-view mirror, and, sure enough, there was an unmarked, late 60’s Chevy, sprouting antennae all over the place. It had government plates and a stony-faced male driver with a crew cut. If I hadn’t known better I’d have thought we were towing him. Even I know a undercover car when I see one.

The driver, whoever he was, eventually pulled away. On arriving in Los Angeles, Lyn and Joyce spent several sweaty hours unloading 37,000 books packed in 50-pound boxes before heading back to Laguna Beach.

There, they waited. Having been advised not to produce any further comics until the Wilsons went to trial, they tried to think of other, more respectable things to do. “I imagine Lyn and I will try to lock into the women’s market,” wrote Joyce to Clay Geerdes on January 2, 1974, “though we have to keep working and right now we aren’t able to do much of anything.”

While the duo waited either for their arrest or their freedom, they worked on grant applications for health education comic books. They toyed around with the idea of a feminist art gallery. They brainstormed a “straight” newspaper strip about a post-menstrual cat named Persephone. But neither felt energized by their new work, nor safe in creating it. Lyn wrote to her friend Don Baumgart on January 12, “Frankly I think I’m incapable of reform. I’ve been trying to project the image of a LADY lately and people just look at me as if I’m an android.”

***

The Wilsons’ case dragged on. Initially meant to go to jury on January 25, the ACLU lawyers managed to forestall their hearing further, hoping for a new ruling on pornography either in California or federally. “Since the new ruling will eradicate any basic issues the attorneys are likely to bring up on the case, foot dragging seems the most sensible thing,” Joyce told Clay Geerdes on February 8. “They are buying time for us while they are at it.”

In fact, they bought the women of Nanny Goat a good deal of time, as the trial kept getting rescheduled. Seven months later, in August of 1974, ACLU was still contesting the Wilsons’ arrest. One attorney argued in Publishers Weekly that “the case should be dismissed on the grounds that the California obscenity legislation is unconstitutional because it is vague and unclear.” Eleven months later, in November, the Wilsons’ trial date was finally set: February 28, 1975. The Los Angeles Times reported at the time that the Wilsons’ attorneys intended to argue that “Laguna Beach is more tolerant than other communities” and to demand a jury “composed solely of Laguna Beach residents.” Such requests caused further delays not only for the Wilsons’ trial, but for Nanny Goat’s business.

“Remember the near bust of us a couple of years ago?” Joyce asked her fellow underground publisher Ron Turner in a letter dated October 27, 1975. “We had lunch with the ACLU lawyers today and that case against the bookstore owners still hasn’t been dismissed, tho [sic] it should be next month. The attorneys said they were sure Lyn and I were in for it and expressed surprise that we ended up with as little trouble as we did.”

A few days after Joyce sent her letter, nearly two years after their arrest, the charges against the Wilsons were finally dropped on October 31, 1975. The District Attorney’s office “felt the comic books no longer would be considered obscene under contemporary community standards,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

By this time, the underground comix market was on the verge of collapse. Jay Kinney described the decline of undergrounds for Heavy Metal in 1980:

Following five years of steady momentum, 1973 saw the UG-comix market crash, as the Supreme Court, a newsprint shortage, and the recession teamed up to bring the pint-sized industry to a standstill. With the main UG publishers poised on the brink of bankruptcy, no comix came out for months on end… For the remaining cartoonists there now seemed little choice but to pursue individual careers.

Despite murmurs from the underground, the women of Nanny Goat were invigorated by the growing women’s publishing market. They started to build up the distribution arm of Nanny Goat Productions, creating a mail order company for their titles as well as other women’s comix. By March of 1976, they had begun work on the second issue of Tits & Clits, which they published in July of the same year.

“Lest you think the world of underground comics is a thing of the past, let me reassure you that it is not,” wrote Lyn in a July 1976 letter. “Even though it is hardly an untroubled pathway to instant riches we intend to continue in our flagrant way.”

Which, over the next four years, they did. The women of Nanny Goat went on to publish four more issues of Tits & Clits before amicably dissolving their business partnership in December of 1980. Lyn went on to publish an erotic novel titled Alida, which she described as “a non-sexist book written from a woman’s point of view.”

In a 1981 interview with Clay Geerdes’ Comix World, Joyce reflected on the bust as well as her and Lyn’s work. “I have never heard a woman actually say T&C was pornographic,” she said. “We originally published T&C as a knee jerk reaction to ZAP. We wanted to do sexual/menstrual stories from a woman’s point of view. If that’s porn, it’s in the eye of the beholder.”

“I’m sure our work is racier than the underwear section of the Sears catalogue,” Lyn concurred in an essay published in Words in Our Pockets (1985), “but to put it on par with Hustler by calling it pornography points to a lack of distinction between the subject of sex and the issue of pornography.”

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Sam Meier is a freelance writer, researcher, and editor based in Vancouver, B.C., where she is a Masters student at the University of British Columbia’s School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies. She is currently at work on a history of Nanny Goat Productions. More of her work on women’s underground comix can be found at her website.