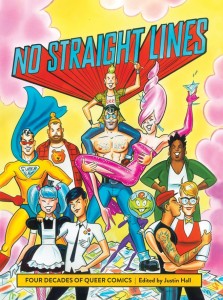

Justin Hall, who brought together the elegant and poignant queer comics anthology, No Straight Lines has been working on a new documentary by the same name with Peabody Award-winning director, Vivian Kleinman. The documentary is set to follow several groundbreaking LBGTQ comic book creators who broke barriers and paved the way for queer comics today.

Justin was kind enough to take some time from his hectic schedule and sit down with CBLDF and discuss censorship, comics in the queer community, and the history of LGBTQ comics.

When you first set out to make No Straight Lines, you endeavored to create a history of queer comics, but the project shifted when you uncovered a history too vast to be contained in one work. Considering the heartbreaking history of violence and intimidation the LGBTQ community experienced, it seems likely that there were times that people were really putting themselves at risk by even telling these stories. Can you talk about the early days of queer comics, and the risks creators took telling their stories?

It’s actually endlessly inspiring to me, thinking about the courage with which these early creators made their work and got it into the world. Tom of Finland, in my mind the first openly gay cartoonist, began his erotic Kake comics in the mid-1960s. They were groundbreaking depictions of gay male sexuality created when that was completely illegal and incredibly dangerous. All of those early queer erotic cartoonists and artists (Etienne, The Hun, The Blade, etc.) had to use pseudonyms to protect themselves, their publishers, and their fans from criminal prosecution. Bob Mizer, publisher of Physique Pictorial magazine, which published Tom of Finland for the first time and gave him his pseudonym, even served 9 months of jail time for distribution of near-nude images of men.

What kinds of censorship did queer comics encounter in your research? How did censorship change over the span of time that you’re covering?

After obscenity laws loosened up there were still plenty of dangers and obstacles, of course, and we’re still fighting battles to this day. Witness the troubles that Jen Camper had with the US Postal Service not distributing her postcards, and the problems that Fun Home has encountered, which you’ve covered at the CBLDF, at secondary schools and universities!

How have the outlets for LGBTQ comics changed over their history? In your view, what impact did the emergence of venues like Gay Comix have upon cartoonists and audiences?

Queer comics existed in a sort of alternative universe to the rest of the comics industry for quite a while, as they weren’t generally sold in comic book stores or mainstream bookstores or serialized in mainstream or even alternative papers and magazines; instead, they were found in the insular LGBTQ media world of queer newspapers, bookstores, publishers, and distributors. Queer content did often show up in the headshops that sold underground comix and in the later punk zine and mini-comic culture, but the mainstream outlets generally eschewed all queer material.

The Gay Comix anthology was a game changer when it appeared in 1980, as it brought together the queer women already creating stories in feminist underground comix with a new batch of queer men interesting in making work beyond just the early erotica. It was in many ways the backbone of LGBTQ comics in the States for the 18 years it was in publication and inspired new generations of queer cartoonists by its very existence; Alison Bechdel, for instance, found a copy of one of the early issues in a gay lesbian bookstore and it was what prompted her to try her hand at making comics. It’s also where the first trans comics appeared: David Kottler in issue #3 with the story “I’m Me” and then Diana Green in issue #19, debuting the first installment of her Tranny Towers series.

How have comics been a part of LGBTQ culture in ways that are specific to that culture? Has that role shifted, in your view?

Bechdel talks about wanting to “make lesbians visible” when she created her seminal Dykes to Watch Out For, and I think that points to the hunger for queer communities to see themselves represented. Comics were (and remain) in many ways the perfect medium in which to achieve that, as they are both visual and narrative. LGBTQ artists, often marginalized economically, socially, and politically, could use the DIY medium of comics to tell their own stories about themselves and for themselves with little censorship or compromise.

Now, of course, that insular LGBTQ media marketplace that nurtured so much comics talent has in large part broken down. There are very few queer bookstores, publishers, and newspapers left as societal oppression has begun to lift and the market has shifted. On the other hand, new opportunities are opening up as the mainstream publishers and retailers are increasingly open to queer content and the web has created new frontiers.

When did the corner turn towards a broader acceptance of LGBTQ content in comics, and in society on the whole?

It’s been a slow and steady shift in the comics world, punctuated by numerous key moments. The Stonewall Riots of 1969, which in many ways sparked the modern LGBTQ rights movement, also inspired the creation of a wave of queer newspapers and magazines that in turn needed comics; this led to everything from the early gay gag strips such as Joe Johnson’s Miss Thing to Rupert Kinnard’s Cathartic Comics and Eric Orner’s The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green.

Then the development of the underground comix, queercore (LGBTQ punk), and riot grrrl movements in the next few decades enabled publications like Wimmen’s Comix, Come Out Comix, Gay Comix, Dyke Strippers, and Boy Trouble to showcase queer content. The mainstream didn’t begin to evolve until later; Jim Shooter, the editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics during the 1980s, famously said, “There are no gays in the Marvel universe.” It wasn’t until 1989 that the first openly gay superhero was created (Extraño, admittedly a horribly stereotypical character) and 1993 that saw the first trans superhero, Coagula, created by the openly trans creator Rachel Pollack in the pages of Doom Patrol. Now, of course, Jughead identifies as asexual, Northstar married his boyfriend, and Wonder Woman is officially bisexual. It’s been a radical transformation!

There has also been a steady shift in the culture of comics; Andy Mangels launched his annual ComicCon panel Gays in Comics (now titled Out in Comics) in 1988, and I began the annual Queer Cartoonists panel, which ran for a dozen years, at the Alternative Press Expo (APE) in 2003. Prism Comics, a non-profit supporting LGBTQ comics, creators, and fans, began in 2003, and now we have Flame Con, a robust queer comics convention, which opened its doors in 2015. The Lambda Literary Awards also started a Graphic Novel category in 2015, showcasing how comics have been welcomed into the queer literary world.

What aspects of history are in danger of being forgotten by younger audiences that you’re hoping to preserve in making this film?

The No Straight Lines film is a different sort of project than the book, as there’s no way to create an overview of a large, complex history in a single feature-length film. Instead, we’ll be focusing on a handful of specific creators (such as Alison Bechdel, Howard Cruse, and Rupert Kinnard) whose work has had an important impact. We feel passionately that creating filmic portraits of these creators whose artistic courage and personal journeys represent the movement of queer comics from fringe underground to mainstream acceptance will both create an engaging and unique window through which people can view LGBTQ history and also inspire future queer cartoonists, academics, and fans. Too often, queer history and comics history aren’t given their due; these stories are important and should not be forgotten!

What do you want future audiences to take from this history, and what contributions do you hope these audiences make to the heritage of LGBTQ comics?

My fondest wish is for my book and my film to inspire some queer kids to pick up a pen for the first time and create their own comics about their own lives!

I remember the absolute last copy of the first print run of the No Straight Lines book, which I sold at ComicCon in 2013; it was to a middle-aged, straight woman buying it for her teenage, gay son. She told me that she was getting the book for him because she wanted him to know his history and lineage, and she couldn’t tell that story to him herself. She thanked me for creating the book for both of them and I promptly burst into tears. Then we hugged it out… It was an incredible moment. And I want that mother and son to go to this film together as well when it comes out, to share some popcorn, laughter, and tears as that same history hits the big screen.

The upcoming documentary has received partial funding from the San Francisco Foundation, California Humanities, and the Berkeley Film Foundation, as well as some generous private investors. Still, feature-length films are expensive, and No Straight Lines is currently finishing up a successful Kickstarter campaign, scheduled to end at 11 a.m., May 23. Watch the Kickstarter trailer below.

Justin and his team have set up some impressive rewards for campaign backers that can be enjoyed immediately. One of the film’s stars Alison Bechdel’s cat Donald, (named after English paediatrician and psychoanalyst, Donald Winnicott) has a distinct ringtone of her meow available for many tiers of supporters.

Check out the campaign. And stayed tuned to CBLDF.org for updates as the film finishes and gets set to release.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2018 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!