Author’s Note: Thanks to Carlotta at 360 Amsterdam and employees of the Anne Frank Fonds working at the Anne Frank House, who answered my many questions. All mistakes are the authors.

“I live in a crazy time”

–Anne Frank

The Year was 1942. Walt Disney’s fifth animated feature, Bambi, was released in theaters. Bing Crosby’s White Christmas was the bestselling song. How Green Was My Valley took the Academy Award for Best Picture. Sensation Comics #1 introduced the world to a new comic book character named Wonder Woman. And, on June 12, a young Dutch girl named Annelies Marie Frank received a red and white checkered autograph book for her 13th birthday.

Anne began writing in her diary two days later. Anne expresses that writing in a diary feels strange for her. And like any other pre-teen, Anne longs for a best friend, someone with whom she can share everything without worrying about how her friend will react. She decides that it would easier if she used a letter format. Instead of writing ”Dear Diary,” Anne begins her diary entries by addressing them to “Kitty or ”Dearest Kitty.” There has been much discussion as to who Kitty is. Some believe it is a reference to childhood friend Kathe “Kitty” Egyedi. Others believe that Kitty is a fictional character in the Cissy van Marxveldt’s Joop ter Heul novels that Anne enjoyed reading. Anne herself writes that Kitty is a completely fictitious imaginary friend:

“To enhance the image of this long-awaited friend in my imagination, I don’t want to jot down the facts in this diary the way most people would do, but I want the diary to be my friend, and I’m going to call this friend Kitty.”

–Diary, June 14, 1942

In the early entries, Anne writes to Kitty about her life. She talks about her father, Otto, her mother Edith, and her sister Margot. And while the earlier entries are what one would usually expect from a preteen/teen: school, boys, and cliques, things take a pretty dramatic change after July 5, 1942.

You see, the Frank family was Jewish and living in German-controlled Amsterdam during the Holocaust.

Annelies “Anne” Marie Frank was born on June 12, 1929, in Frankfurt, Germany. But like the 300,000 other Jewish Germans who faced anti-Jewish legislation and state-sponsored persecution, Otto Frank knew he had to escape. The Frank family fled Germany to Amsterdam after the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party. Anne tells Kitty, “As we are Jewish, we emigrated to Holland in 1933.”

Anne and her family lived in a three bedroom apartment on the second floor at 37 Merwedeplein. It was at this address that Anne began writing in her diary at a small writing desk. And while the house is not open to the public, visitors can still see the four Stolpersteine (literally “stumbling stones”) created by the German artist Gunter Demnig that memorialize the Frank family’s residence. Each stone has a brass plate with a name, date of birth, deportation date, place and date of death.

And while the Frank family initially prospered in Amsterdam, by May of 1940, it became clear that they hadn’t fled far enough. The German army invaded and conquered the Netherlands. With German occupation came anti-Jewish laws, mandatory registration and eventual deportation. Anne chronicles many of these restrictions in a June 29, 1942 entry in her diary, including forcing Jews to wear a yellow star, handing in their bicycles, being banned from driving and public transportation, limiting the time and place for shopping, imposing an 8 o’clock curfew, segregating schools, and preventing any sort of public recreation.

Once again, Otto knew he needed to do something to save his family.

After a failed attempt to escape to the United States, Otto and Edith decided that it would be best for the Frank family to hide in the Secret Annex he purchased and wait out the German occupation. Although they had originally planned to go into hiding on July 16, 1942, these plans were accelerated after Margot received relocation orders from the Central Office for Jewish Emigration. With their daughter sentenced to a Nazi work camp, the Franks were forced to go into hiding a week earlier, on the morning of July 6, 1942. Anne brought her diary with her.

The Franks hid in a three-story Annex connected to the offices of the businesses that Otto Frank had managed and owned until he was forced to relinquish them for fear of German confiscation. Only accessible through a hidden bookcase, the Frank’s hiding place became known among its occupants as the Achterhuis — the Secret Annex — among the few that knew of its existence.

The Frank family was soon joined by others, who also fled to the Secret Annex to hide from Nazi persecution. First, there was the Van Pels family, which consisted of Herman, his wife August and their 16 year-old son Peter. They were eventually joined by Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist, whom Anne was forced to share a room with.

Other than the residents, only a handful of trusted employees knew about the inhabitants of the Secret Annex. These brave individuals risked the death penalty for sheltering Jews, yet they still provided to all the needs of the families, gave updates as to the state of the outside world, and, most importantly, kept them safe from discovery.

Of course, Kitty also knew. Because Anne writes to her nearly every day. Kitty patiently listens to all of Anne’s hopes and fears as she writes about life in hiding. Kitty receives descriptions of Anne’s daily activities and interactions with her housemates. Kitty listens as a fearful Anne tells tales of close calls and near discovery, as Anne gives vivid descriptions of air raids, and how it feels to watch bombs fall from the sky. Kitty is also privy to humorous anecdotes as the Annex residents try to make the best of their confinement. Anne copies the funny rules that they have created, including the fact that the Annex is “open all year round,” that holidays are “postponed indefinitely,” and that “all civilized languages are permitted, therefore no German!” And Kitty is there as Anne describes what happened to Anne’s friends that were sent to concentration camps and reports on the status of the war.

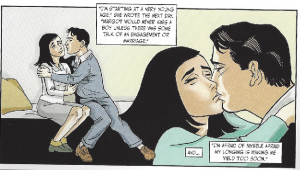

But, the diary contains more than a mere chronology of life in the Annex. Anne writes to Kitty about more personal things. She writes of her frustrations with her housemates, her immense love for her father, her newfound closeness to her sister, and Anne’s frustration and eventually acceptance as she comes to terms with her intense dislike of her mother. Anne expresses her guilt at learning the final fate of many of her classmates while she is safely hiding in the Annex. Anne shares intimate details with Kitty about her newfound romance with housemate Peter. Anne even writes about the secret things she teaches and learns from Peter about sex, and quite openly discusses menstruation, sex organs, gay experimentation, god, and human nature with a frankness and maturity far beyond her young age. Kitty was privy to Anne’s deepest thoughts, hopes, and fears. As the imaginary friendship grows, Anne sometimes refers to Kitty as Kit or other more informal names.

The diary was initially intended to be private as Anne originally believed “that neither I—nor anyone else—will be interested in the chatterings of a thirteen year old schoolgirl” But, on March 29, 1944, Anne’s thoughts turned to publishing her diary after she heard Gerrit Bolkestein, an exiled cabinet minister, on the radio. Bokestein announced that the government would collect diaries and letters once the war ended. Upon hearing this, Anne once again looked hopefully to the future as she spent time editing and expanding her earlier entries. She also began creating a second version of the diary in which she gave everyone involved pseudonyms.

It is clear from even before becoming a prisoner of the Annex that Anne wanted to a writer. Anne speaks with pride about her creative writing assignments and humor essays that she wrote in school prior to her life in the Annex. She tells Kitty about her goals and dreams of what will happen when she finally leaves the crowded Annex and her future career as a writer and a journalist. On April 5, 1954, Anne told Kitty:

“I can shake off everything if I write, my sorrow disappear, my courage is reborn. But, and that is the great question, will I ever be able to write anything great, will ever become a journalist or a writer? I hope so, oh, I hope so very much, for I can recapture everything when I write, my thoughts, my ideals and my fantasies.

. . .

So I go on again with fresh courage, I think I shall succeed, because I want to write!”

After two years in the Annex, it became clear that the war would be coming to an end soon. On April 11, 1944, Anne writes, “Sometime this terrible war will be over. Surely the time will come when we are people again, and not just Jews.” In June, Anne writes of allied victories and her hopes that the war will soon be over. She mentions D-Day on June 6, 1944. Then, on June 9th, Anne tells Kitty that, “Excitement here has worn off a bit, still, we are hoping that the war will be over at the end of this year.”

Anne wrote faithfully to Kitty from 1942 to 1944. By the end of 1942, Anne had filled up the original diary. The entries soon expanded beyond the original book and into several notebooks, some of which have been lost to time, as well as several hundred loose pages, which she intended to use to rewrite the diary into a novel. The last entry in the diary is August 1, 1944. In it, Anne is introspective in her soul searching and while it was written by a fourteen year-old girl almost 75 years ago, Anne’s writing is intelligent and feels contemporary as she examined the same questions of identity that face teens today.

There would be no more letters to Kitty as the Secret Annex came under siege by German police on the morning of August 4, 1944. As part of the raid, the police ransacked the Annex and left Anne’s diary scattered along the floor, where it was saved from extinction by Miep Gies and Bep Voskuji, two of the employees that helped the residents of the Annex. They kept the diary because they knew Anne would want it after the war. The women did not read the diary to respect Anne’s privacy. Because if they did, they admitted that they would have destroyed the book because it contained too much incriminating information.

After their arrest, the Franks were quickly sentenced to work camps for hard labor for the crime of being “Jews in hiding.” On September 3, 1944, the Frank family was placed on the last transport out of Amsterdam and sent to Auschwitz, one of Germany’s 40,000 concentration camps. There, Otto Frank was separated from his family and forced to do hard labor. It was there that Edith was separated from her children. It was there that Margot and Anne contracted scabies. It was there that Edith Frank died of starvation because she saved every morsel of her food to give to her sick daughters through a small hole in the infirmary fence.

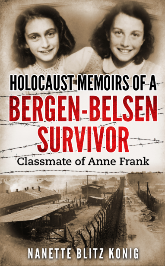

Margot and Anne would eventually be transferred to another camp called Bergen-Belsen. One of her classmates, Nanette Konig, remembered seeing Anne at the camp. Anne had been through so much that she looked “finished off” and “barely recognizable”. Believing her entire family was dead or dying, the once strong-willed teen from the Secret Annex had given up hope.

The sick and frail Margot died in early 1945 when she fell from her bed. Anne followed her sister a few days later, when she died of typhus. Soon after, British soldiers liberated the Bergen-Belsen Camp. But it was too late for Anne and Margot.

Both girls were buried in an unmarked mass grave.

Of the estimated 137,000 Jews living in the Netherlands, approximately 107,000 were deported back to Germany. After the war, only 5,000 survived. It is also estimated that one-third of the 30,000 Jews who remained in the Netherlands were also killed. Nearly six million European Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, roughly two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe. Included in this number are the lives of Herman, August and Peter Van Pels, Fritz Pfeffer, and Ellen, Margot and Anne Frank.

The only surviving resident of the Secret Annex was Otto Frank, who returned home to Amsterdam and was heartbroken to find that his entire family had died. Otto also discovered Anne’s diary had been saved. He later described, in an afterword to the diary, what it was like to read the pages:

“For me, it was a revelation. There, was revealed a completely different Anne to the child that I had lost. I had no idea of the depths of her thoughts and feelings.”

Knowing of Anne’s desire become an author, Otto dedicated himself to getting the diary ready for publication. He combined both versions of Anne’s diaries for publication. Certain portions of the diary involving Anne’s initial feelings about her mother and her sexuality were omitted. Although the diary was initially unable to find a publishing home, things changed after the diary was featured in an article called a “Child’s Voice” appeared on the front page of the April 3, 1946, edition of the Dutch newspaper Het Parool, formerly the newspaper of the Resistance. Written by historian Jan Roman wrote:

“To me, however, this apparently inconsequential diary by a child… stammered out in a child’s voice, embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence at Nuremberg put together.”

As a result of the article, several publishers become interested in the diary. Eventually, Contact in Amsterdam was selected to be the publisher. Despite Otto’s earlier revisions, the Director of the publisher felt that Anne still talked too much about her sexuality and censored even more paragraphs from the manuscript.

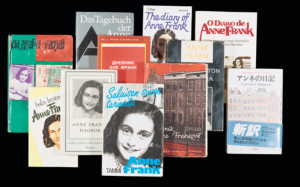

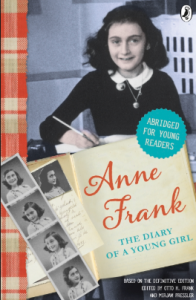

The diary was first published in the Netherlands as Het Achterhuis (The Annex) in 1947. Shortly thereafter, the book was translated into several languages and quickly became a bestseller in France (Le journal d Anne Frank), Germany (Anne Frank Tagebuch), the United States (The Diary of a Young Girl) and Japan. The German version was further censored by the publisher to remove anything that would be offensive to German readers. The introduction of the English publication was written by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Despite success in these other markets, the diary did not sell well in the United Kingdom, where it quickly fell out of print.

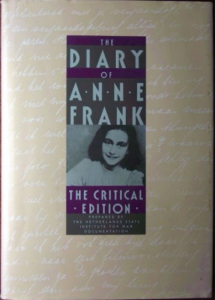

Otto Frank died in 1980, and willed Anne Frank’s manuscript to the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation. Eventually, the portions of the book removed by Otto and the publisher, roughly 30 percent of the book, were added back to the diary in the Critical Edition in 1987 and Definitive Edition in 1995. Earlier this year, even more material became available when researchers were able to restore even more of the diary.

This diary has been translated into the over 70 languages and has sold over 30 million copies. The Diary of a Young Girl has become part of High School curriculums in the United States.

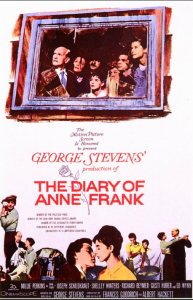

The overall success of Anne’s story has led to the diary being adapted into several other mediums. A play by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich based on the diary won the Pulitzer Prize for 1955. A movie based on the play earned an Academy Award for Shelley Winters, who donated her Oscar to the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. The biography of Anne Frank was also made into an Emmy Awarding television mini-series in 2001 starring Ben Kingsley. Several other plays and movies have been made since with varying degrees of success.

The book has also been transformed into a manga and an anime film in Japan, Anne no Nikki.

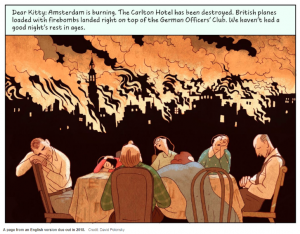

Several graphic novels have also been made, including, Anne Frank from Gareth Stevens Paperback, an authorized graphic biography edition released by The Anne Frank Foundation which is being turned into an animated film, and an upcoming graphic novel from Penguin Books.

Anne’s time in the Secret Annex has even been made into an Oculus virtual reality experience.

Of course, the book’s blunt discussion of sensitive issues like sexuality and religion, have placed it at the center of some controversy. Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania discovered that some American school libraries have banned or censored the book because Anne writes bluntly about her menstruation. The American Library Association stated that there have been six challenges to the book in the United States since it started keeping records on bans and challenges in 1990, and “Most of the concerns were about sexually explicit material”. The most outrageous of these complaints occurred in 1983 from an Alabama textbook committee that said the book was “a real downer” and called for its rejection from schools.

In 1982, the book was challenged in Wise County, Virginia because parents complained that the book contains sexually offensive passages and undermined adult authority when Anne criticizes her mother.

In 1998, the Baker Middle School in Corpus Christi, Texas removed the book from its library after two parents complained that it was pornographic. However, the students fought back and waged a letter-writing campaign to keep it, which persuaded the review committee to recommend that book stay on shelves.

In 2009, the diary was translated into Arabic and Farsi by the Paris-based Aladdin Project, which aims to spread awareness of the Holocaust and counter racism and intolerance. In response, Hezbollah asked Lebanese officials to prosecute those responsible for the distribution of the book and called for the book to be banner in Lebanese schools because they claimed the diary promoted Zionism. In response, a Beirut school removed a textbook containing excerpts of The Diary of Anne Frank from its syllabus.

In 2010, the Culpeper County, Virginia school system banned the 50th Anniversary Definitive Edition of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl after a parent complained of sexual themes, including sexual content and homosexual themes. However, after consideration, it was decided a copy of the newer version would remain in the library and classes would revert to using the older version.

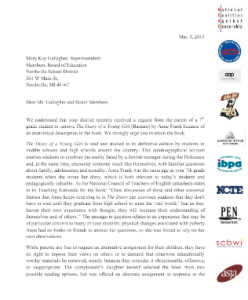

In 2013, a mother of a 7th grade student filed a formal complaint in Northville, Michigan because she felt the explicit passages about sexuality were pornographic. In response, Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, and nine other free speech organizations signed a letter to urging them to keep the Definitive Edition of Anne Frank’s A Diary of a Young Girl in middle school classrooms. They wrote:

”Literature helps prepare students for the future by providing opportunities to explore issues they may encounter in life. A good education depends on protecting the right to read, inquire, question and think for ourselves. We strongly urge you to keep The Diary of a Young Girl in its full, uncensored form, in classrooms in Northville.”

The reconsideration committee voted to keep the book. Assistant Superintendent Bob Behnke wrote that “The committee felt strongly that a decision to remove the use of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl – The Definitive Edition as a choice within this larger unit of study would effectively impose situational censorship by eliminating the opportunity for the deeper study afforded by this edition.”

In 2014, more than 300 copies of the diary and other books on the Holocaust were found vandalized in 31 municipal libraries in Japan. The Israeli embassy donated 300 books about Anne Frank to the Tokyo public library system, to replace the damaged copies. An anonymous donor under the name of ‘Chiune Sugihara’ also donated two boxes of books pertaining to the Holocaust to the Tokyo Central Library. And although the police made an arrest in the case, they did not indict the person because they found the person to be mentally incompetent.

In fact, even though several schools teach about Anne Frank, they do not use the diary at all. Instead, they use the Pulitzer Prize-winning play by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich, which is based on the earlier version of the book. Some use the movies and the mini-series. A few use the censored edition. It appears that no one uses the uncensored version as part of their lesson plan.

Censored or not, the diary still stands as the embodiment of hope and a monument to the indestructible nature of the human spirit while also representing a tragedy of lost potential and serves as a reminder of the horrors of the Holocaust. The reader becomes Kitty, a helpless observer to what is occurring. Readers become Anne’s closest friend. Readers see into Anne’s soul and can only sympathize, fully aware of what is coming for her. But the censored version only presents half the picture. The Anne that wrote to Kitty in the censored version is a flawless ideal and the embodiment of youthful spirit in the face of tragedy. In contrast, the Anne that wrote to Kitty in the uncensored version is a real teenage girl. She is insecure as she tries to deal with her emerging sexuality and stumbles through her first romantic relationship. The real Anne fights with her family, throws tantrums, and has issues with her mother. The uncensored version presents an Anne that is a real and vulnerable girl on the cusp of becoming a woman.

In the words of Anne’s cousin, Buddy Elias, who spoke in 1996 about the Anne that appears in Definitive Edition of the Diary:

”It’s really her. It shows her in a truer light, not as a saint, but as a girl like every other girl. She was nothing, actually; people try to make a saint out of her and glorify her. That she was not. She was an ordinary, normal girl with a talent for writing.”

There is a statue of Anne Frank in Amsterdam near the Westerkerk. It is not very ornate or even very large. Instead, the statue is the perfect representation of a little girl who went through so much and who brought awareness to the world.

Anne Frank was a normal girl who just wanted to grow up. She wanted to become a journalist. Most importantly, she just wanted to have a normal full life. She was unable to do any of these things because of hatred and prejudice thrust upon her because she was born Jewish.

This is the version that should be remembered.

This is the version that censorship does not let you see.

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and award-winning author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, superhero, and young adult genres. He most recent books are the graphic novel Great Zombies in History from McFarland Press and the young adult novel Sky Girl and the Superheroic Adventures from Martin Sister Publishing. Look for his new book, Comic Book Law: Cautionary Tales for the Comics Creator, from McFarland Press. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2018 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!