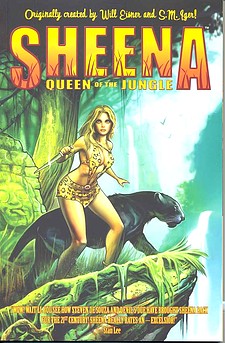

The comic books of the Golden Age represented little more than escapism for millions of readers. And no one provided escape better than Sheena Queen of the Jungle, whose exotic adventures and good girl art titillated male readers and spawned an entire genre of Jungle Girls. However, Sheena, a hunter who defeated every challenge she faced in the jungle, soon found herself among the hunted as the anti-comics crusaders turned their sites on the Jungle Girls.

The comic books of the Golden Age represented little more than escapism for millions of readers. And no one provided escape better than Sheena Queen of the Jungle, whose exotic adventures and good girl art titillated male readers and spawned an entire genre of Jungle Girls. However, Sheena, a hunter who defeated every challenge she faced in the jungle, soon found herself among the hunted as the anti-comics crusaders turned their sites on the Jungle Girls.

I recently visited the National Zoo with my daughter for a FONZ charity event. (That’s Friends of the National Zoo and not Arthur Fonzerelli from Happy Days). At this event, we saw a listing of all of the animals that have become extinct or are close to extinction. There was groups like the Blue Antelope, North African Elephant, and the Red Gazelle, which will never be seen again, as well as other endangered species such as the Mountain Zebra, the Pygmy Chimpanzee, and the Lowland Gorillas, which may yet be saved.

I recently visited the National Zoo with my daughter for a FONZ charity event. (That’s Friends of the National Zoo and not Arthur Fonzerelli from Happy Days). At this event, we saw a listing of all of the animals that have become extinct or are close to extinction. There was groups like the Blue Antelope, North African Elephant, and the Red Gazelle, which will never be seen again, as well as other endangered species such as the Mountain Zebra, the Pygmy Chimpanzee, and the Lowland Gorillas, which may yet be saved.

Being a comic geek, seeing all of these magnificent endangered creatures led me to think about fictional residents of the jungle that were nearly made extinct in the 1950s: Jungle Girls. This week, we talk about the rise and fall of Sheena and the Jungle Girl comic genre.

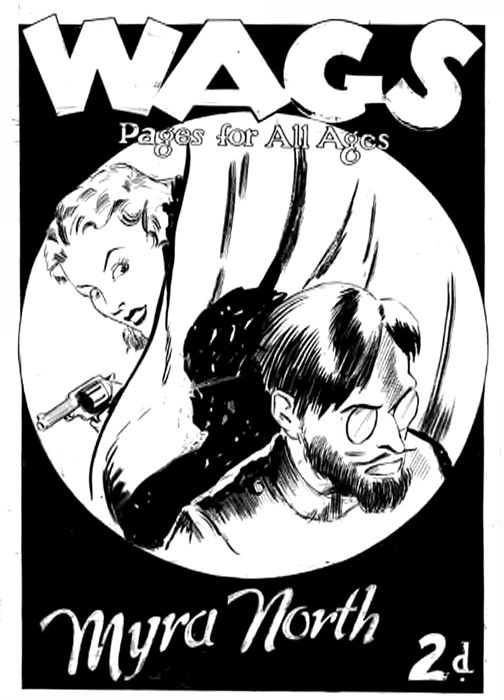

The year was 1937. The first full length animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, debuted at the Cathay Circle Theater. Music fans enjoyed hits from Benny Goodman, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington. The first science fiction convention was held in Leeds, England. FDR started his second term. And radio fans were glued to their sets as they heard Herbert Morrison describe “the humanity” of the Hindenburg disaster. In comics, readers see the debut of Detective Comics #1, (the Dark Knight known as Batman would makes his debut in the United States 27 issues later). Across the pond, comic fans were treated to a different type of comic book character as Sheena made her debut in Wags #1.

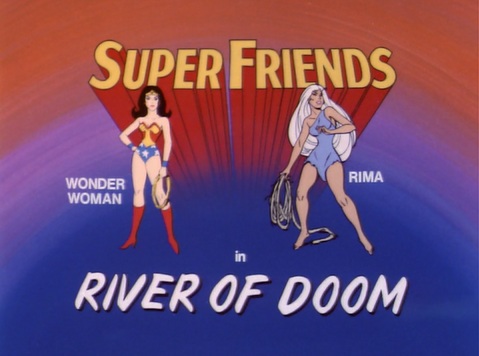

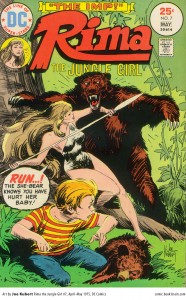

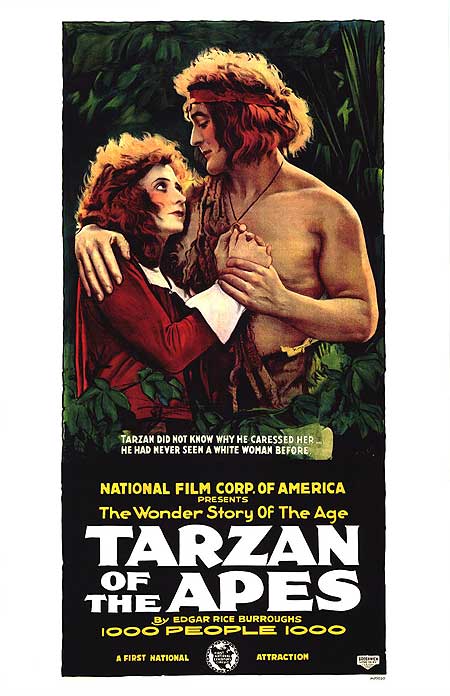

Sheena is not the first jungle girl to exist, as the pulps were full of them. Of course, the most famous is Tarzan’s main squeeze, Jane Porter, introduced by Edgar Rice Burroughs in 1912’s Tarzan of the Apes, and who also appears in nine of the twenty five sequels. Of course, the Jungle Girl phenomenon even pre-dates Jane as Rima the Jungle Girl came on the scene a decade earlier in W. H. Hudson’s novel Green Mansions. If Rima the Jungle Girl, sounds familiar, that may be because she not only had her own DC Comics series in 1974, but also appeared in several episodes of the All New Superfriends Hour cartoon show a few years later (initially voiced by Shannon Farnon, who also did the voice of Wonder Woman, and later portrayed by Kathy Garver, who played Cissy on Family Affair and did the voice of Firestar on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends).

Sheena is not the first jungle girl to exist, as the pulps were full of them. Of course, the most famous is Tarzan’s main squeeze, Jane Porter, introduced by Edgar Rice Burroughs in 1912’s Tarzan of the Apes, and who also appears in nine of the twenty five sequels. Of course, the Jungle Girl phenomenon even pre-dates Jane as Rima the Jungle Girl came on the scene a decade earlier in W. H. Hudson’s novel Green Mansions. If Rima the Jungle Girl, sounds familiar, that may be because she not only had her own DC Comics series in 1974, but also appeared in several episodes of the All New Superfriends Hour cartoon show a few years later (initially voiced by Shannon Farnon, who also did the voice of Wonder Woman, and later portrayed by Kathy Garver, who played Cissy on Family Affair and did the voice of Firestar on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends).

But I digress. Prior to 1937, the Jungle Girls may have existed in the pulps and movies, but not in the comic book world. Before Sheena, there had never been a comic book heroine like her. In fact, some credit Sheena as the first heroine to star in her own comic book, as she predates Wonder Woman’s debut by several years. She would also later become the first heroine to have her name in the title of a book. (Once again, the Jungle Queen would beat the Amazon Princess, who came in second for the honor four months later.

![]() Of course, at her heart, Sheena was a child of the pulps and owed much of her origin to them. There are undeniable and admitted similarities between the imperious and immortal beauty Ayesha, she-who-must-be-obeyed in H. Rider Haggard’s She and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. Even the locale of Sheena books lends itself to another of Mr. Haggard’s works. King Solomon’s Mines (published the year before She) glamorized the mysterious and forbidden Dark Continent known as Africa. To pulp and comic readers, Africa provided a fantastic world of savagery that rivaled the planet Barsoom, with Sheena playing the role of savage temptress the way Deja Thorus did in Burroughs’s Princess of Mars. And many other great genre authors of the time set their adventures in exotic locations to allow their protagonists to have fantastic journeys. For example, Jules Verne’s work took readers into lost worlds, to the moon, to the center of the Earth, and even 20,000 leagues under the sea. Of course, one cannot discuss Sheena without mentioning Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan books, but I would also be remiss if I did not also include Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book as a precursor to both Tarzan and Sheena, as it also popularized both being raised in the wild (although the book was set in India) and glamorized tales of the darkest jungles and battles with wild animals.

Of course, at her heart, Sheena was a child of the pulps and owed much of her origin to them. There are undeniable and admitted similarities between the imperious and immortal beauty Ayesha, she-who-must-be-obeyed in H. Rider Haggard’s She and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. Even the locale of Sheena books lends itself to another of Mr. Haggard’s works. King Solomon’s Mines (published the year before She) glamorized the mysterious and forbidden Dark Continent known as Africa. To pulp and comic readers, Africa provided a fantastic world of savagery that rivaled the planet Barsoom, with Sheena playing the role of savage temptress the way Deja Thorus did in Burroughs’s Princess of Mars. And many other great genre authors of the time set their adventures in exotic locations to allow their protagonists to have fantastic journeys. For example, Jules Verne’s work took readers into lost worlds, to the moon, to the center of the Earth, and even 20,000 leagues under the sea. Of course, one cannot discuss Sheena without mentioning Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan books, but I would also be remiss if I did not also include Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book as a precursor to both Tarzan and Sheena, as it also popularized both being raised in the wild (although the book was set in India) and glamorized tales of the darkest jungles and battles with wild animals.

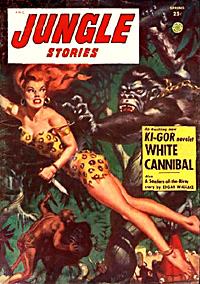

When Sheena was released, the creators of Sheena even used the literary sounding pen name of “W. Morgan Thomas.” Interestingly, Sheena would eventually appear in the pulps that inspired her and had four short stories that appeared in Stories of Sheena Queen of the Jungle, published by Real Adventures Publishing in 1951, and the Spring 1954 issue of Jungle Stories (all printed by Fiction House’s pulp division).

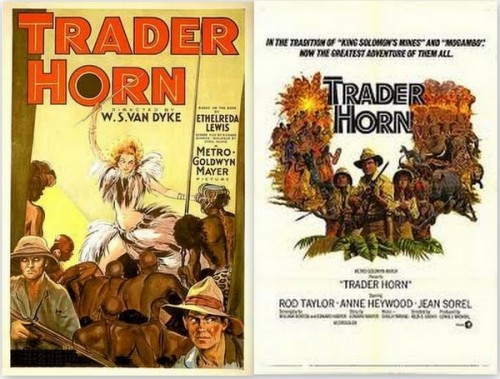

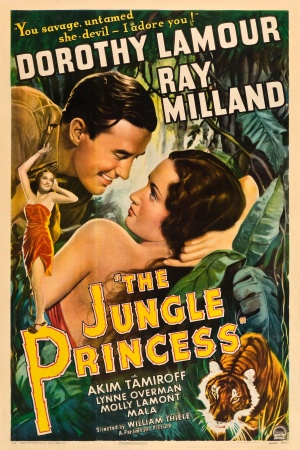

Because of the success of these pulp magazines, with their fantastic action and exotic locations, there could be little doubt that these stories would expand into the new visual medium of film. Once again, Tarzan led the way in 1918 with Tarzan of the Apes, a silent movie that starred Elmo Lincoln as Tarzan and Enid Markey as Jane. The film would be one of the first movies to earn over a million dollars. As a result, the film spawned two sequels and led to the “Jungle Movie” genre. It wasn’t long before filmmakers discovered how to exploit the power of the exotic jungle girl in silent movies such as The Jungle Goddess in 1922 and Lorraine of the Lions in 1925. In 1931, Trader Horn garnered an Academy Award for the fact that it was the first jungle film shot on location in Africa (I’m sure that Edwina Booth’s revealing costume as the White Goddess didn’t hurt the nomination). Of course, Tarzan returned, this time with Johnny Weissmuller as the Ape King and several Janes (most notably Maureen O’Sullivan as a no-nonsense heroine). Finally, screen icon Dorothy Lamour made her debut as “Ulah” in The Jungle Princess before joining Bob Hope and Bing Crosby on their many “Road to” movies.

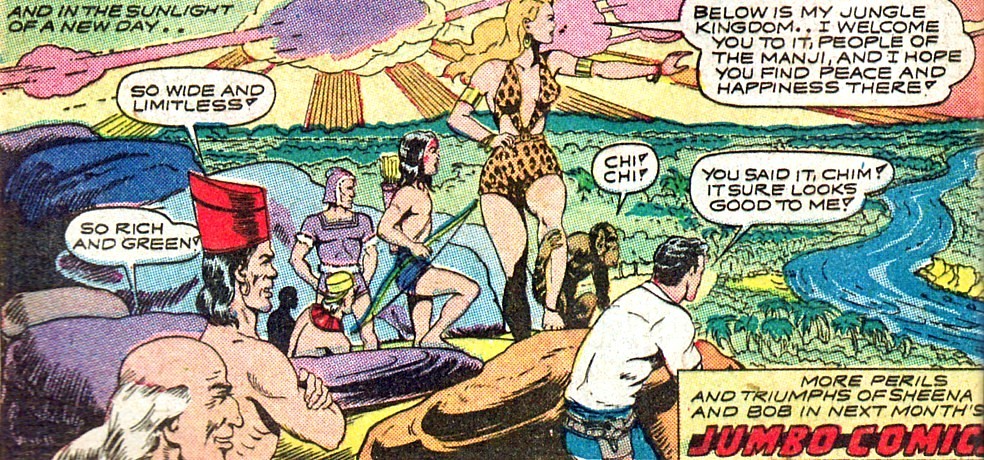

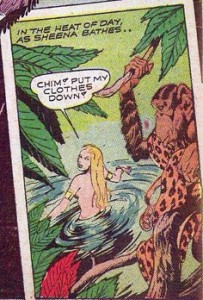

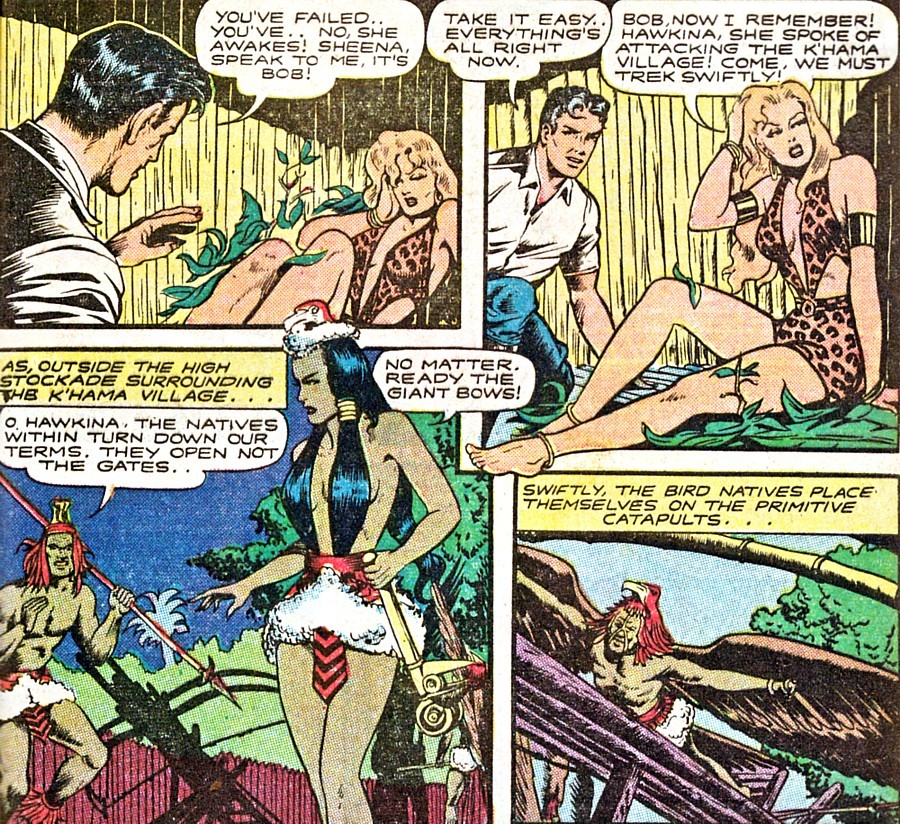

Sheena’s origin is quite simple and prototypical of the stories that had come before. Sheena was a child of explorer Cardwell Rivington, who came to Africa. However, after her father is accidentally killed by drinking a magic potion made by a native witch doctor named Koba, Sheena becomes an orphan in strange land. A remorseful Koba feels honor bound to raise the young blonde girl as his own daughter. To honor all her heritages, Koba teaches Sheena native languages of Africa, English, and the ways of the jungle. Like Tarzan, the grown Sheena becomes queen of the jungle (and even gets a pet monkey named Chim). Sheena eventually meets an inept white hunter named Bob Reynolds (sometimes called Bob Reilly or Rayburn), who she takes as her mate (yes “mate” and not “boyfriend”). Sheena spends most of her stories fighting evil white hunters, slave traders, misguided natives, and the occasional wild animal.

I should also mention that Bob is a typical damsel in distress and Sheena also has to constantly rescue him. I have to assume that the predominately male fans of Sheena were willing to overlook Bob’s emasculating behavior because at the end of the day, for all his ineptitude, he gets to be Sheena’s mate in every way (I’m sure Barney Stinson has a Bro Code rule to cover this). In later incarnations Bob Reynolds became Rick Thorne. Her father also somehow became deceased missionaries and Koba became a female witch doctor named N’bid Ela, but those kind of changes are pretty common in the Golden Age.

I should also mention that Bob is a typical damsel in distress and Sheena also has to constantly rescue him. I have to assume that the predominately male fans of Sheena were willing to overlook Bob’s emasculating behavior because at the end of the day, for all his ineptitude, he gets to be Sheena’s mate in every way (I’m sure Barney Stinson has a Bro Code rule to cover this). In later incarnations Bob Reynolds became Rick Thorne. Her father also somehow became deceased missionaries and Koba became a female witch doctor named N’bid Ela, but those kind of changes are pretty common in the Golden Age.

How Sheena came to be is more complicated. What is known is that Sheena was created by Will Eisner and S.M. “Jerry” Iger of the comic-book packager Eisner & Iger. At that time, the Eisner and Iger studio produced comics on demand for publishers and syndicates. In Sheena’s case, Editors Press Service distributed the feature to Wags. Of course, who actually created Sheena is a matter of debate.

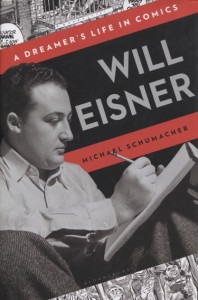

On one side, Iger’s biography (Iger’s Comic’s Kingdom written by Jay Edward Disbrow, which was reprinted in Alter Ego 21) says that Iger was asked to create a Tarzan knock-off and came up with concept of a jungle heroine (he named her Sheena as a variation on a Jewish ethnic slur, “Sheenie”). In an epilogue, Iger writes, “Some people have thought Will [Eisner] also had a role in the creation of Sheena, but the closest Will got to “Sheena” was to do the art for a cover or two, long after the character had been published by Wags.” On the other side, Michael Schumaker, in Will Eisner: A Dreamer’s Life in Comics writes that “the [Iger] biography is marred by historical inaccuracies, the result of Iger’s revisionist history and insistence on taking credit for just about everything that happened in early comics History.” Instead, Will Eisner created Sheena as a female counterpart to Tarzan, and that he named and character from H. Rider Haggard’s character “She” (as in “She-who-must-be-obeyed”).

On one side, Iger’s biography (Iger’s Comic’s Kingdom written by Jay Edward Disbrow, which was reprinted in Alter Ego 21) says that Iger was asked to create a Tarzan knock-off and came up with concept of a jungle heroine (he named her Sheena as a variation on a Jewish ethnic slur, “Sheenie”). In an epilogue, Iger writes, “Some people have thought Will [Eisner] also had a role in the creation of Sheena, but the closest Will got to “Sheena” was to do the art for a cover or two, long after the character had been published by Wags.” On the other side, Michael Schumaker, in Will Eisner: A Dreamer’s Life in Comics writes that “the [Iger] biography is marred by historical inaccuracies, the result of Iger’s revisionist history and insistence on taking credit for just about everything that happened in early comics History.” Instead, Will Eisner created Sheena as a female counterpart to Tarzan, and that he named and character from H. Rider Haggard’s character “She” (as in “She-who-must-be-obeyed”).

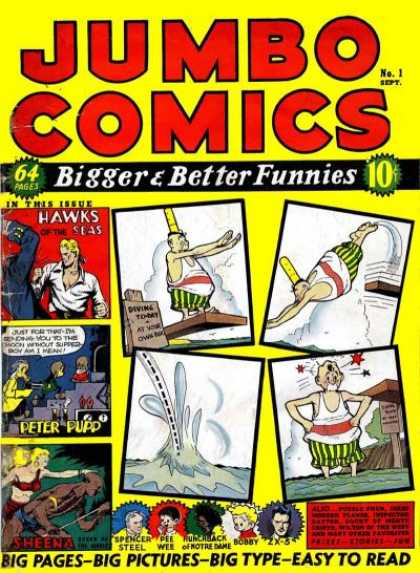

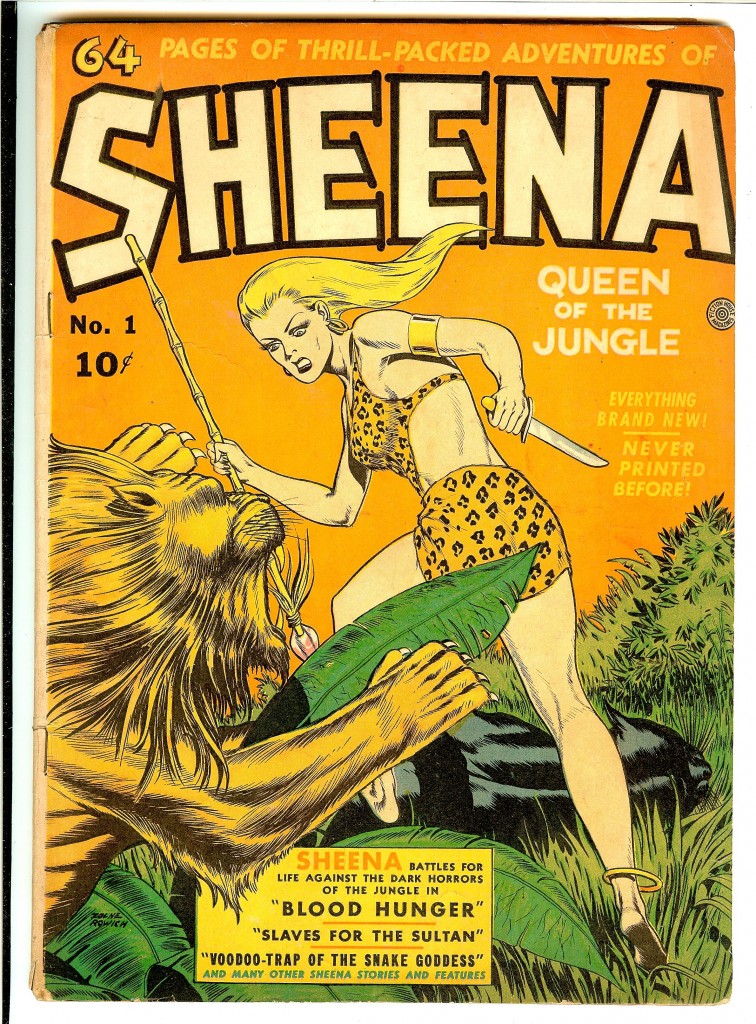

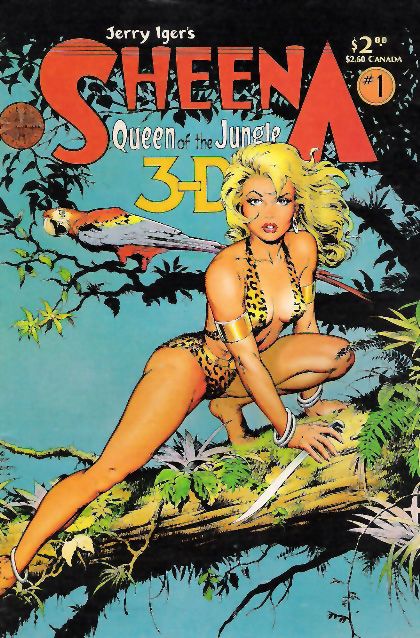

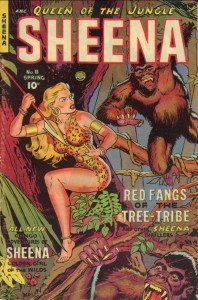

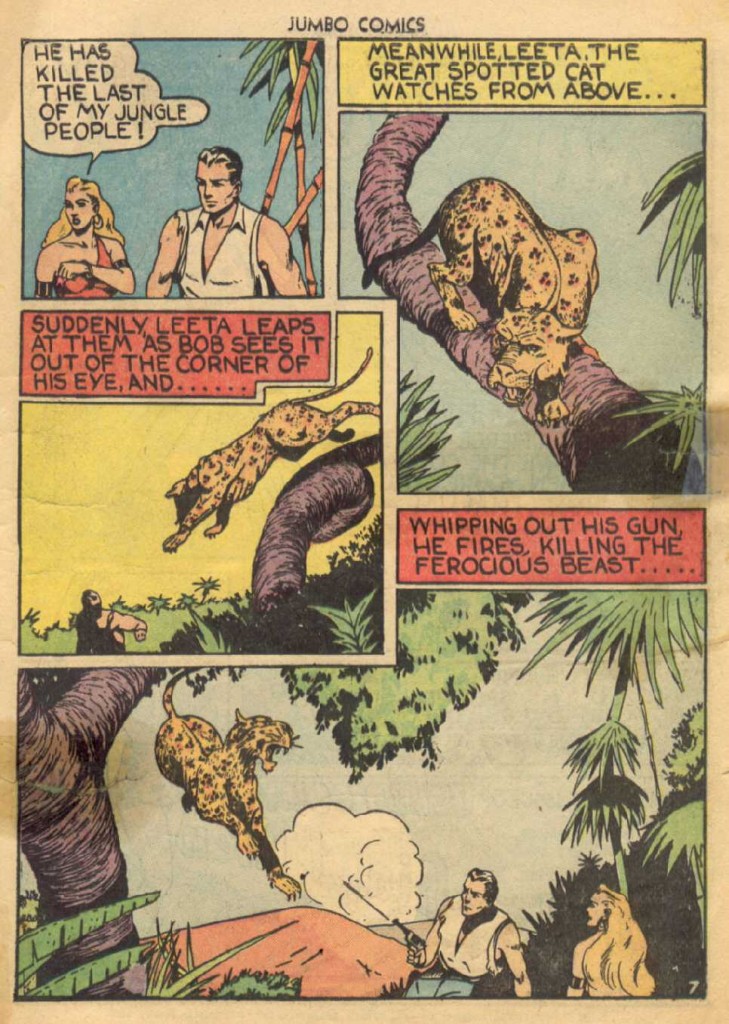

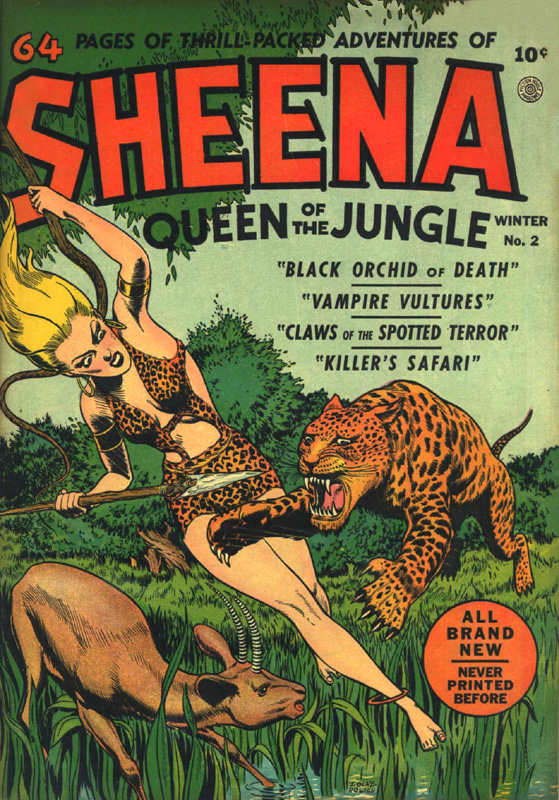

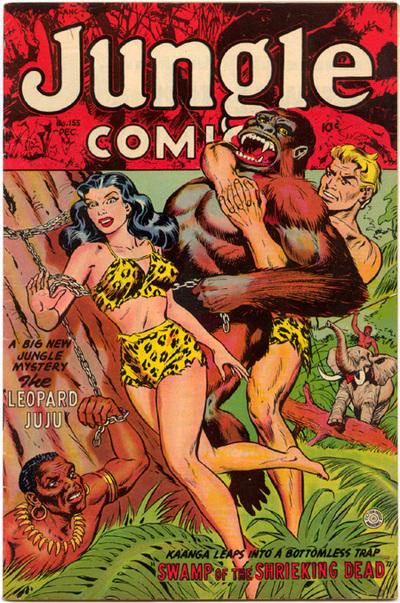

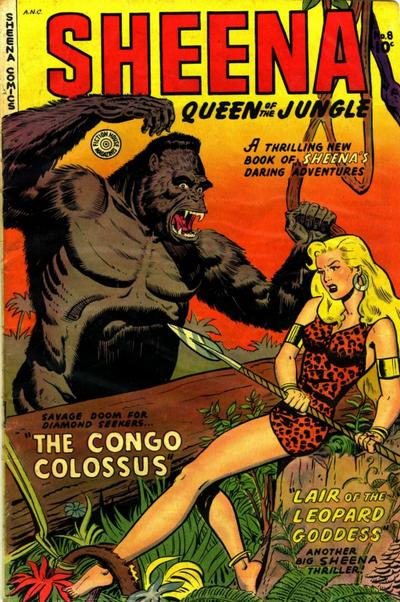

Sheena debuted in Wags #1 in 1937. A year later, a reprint of that story appeared in the United States as part of Jumbo Comics from Fiction House. I should note that the book was called “Jumbo” so that the publisher could re-use the same printing plates utilized in the printing of the tablet-sized Wags (10.5 inch x 14.5 inch / 26.5 cm x 37 cm). And while Sheena shared this comic with other characters such as The Hawk, Agent ZX-5, Midnight, Inspector Dayton, and Stuart Taylor, she would eventually take over the book and become the sole feature in it. In fact, Sheena not only appeared in every one of the book’s 167 issue run, but she also was given her own self-titled comic that ran for eighteen issues and made appearances in Jungle Comics and Ka’anga. Sheena’s last comic book appearance in her original run was in 3-D Sheena Jungle Queen, published by Fiction House in 1953.

Jay Disbrow, in Alter Ego 21, writes

From the onset Sheena captivated the minds of comics readers. The concept of a white woman raised in the wilds of equatorial Africa, being forced to pit her wits and survival instincts against savage beasts, primitive natives, and the forces of nature: these elements of the story exercised the fascination of comic book readers.

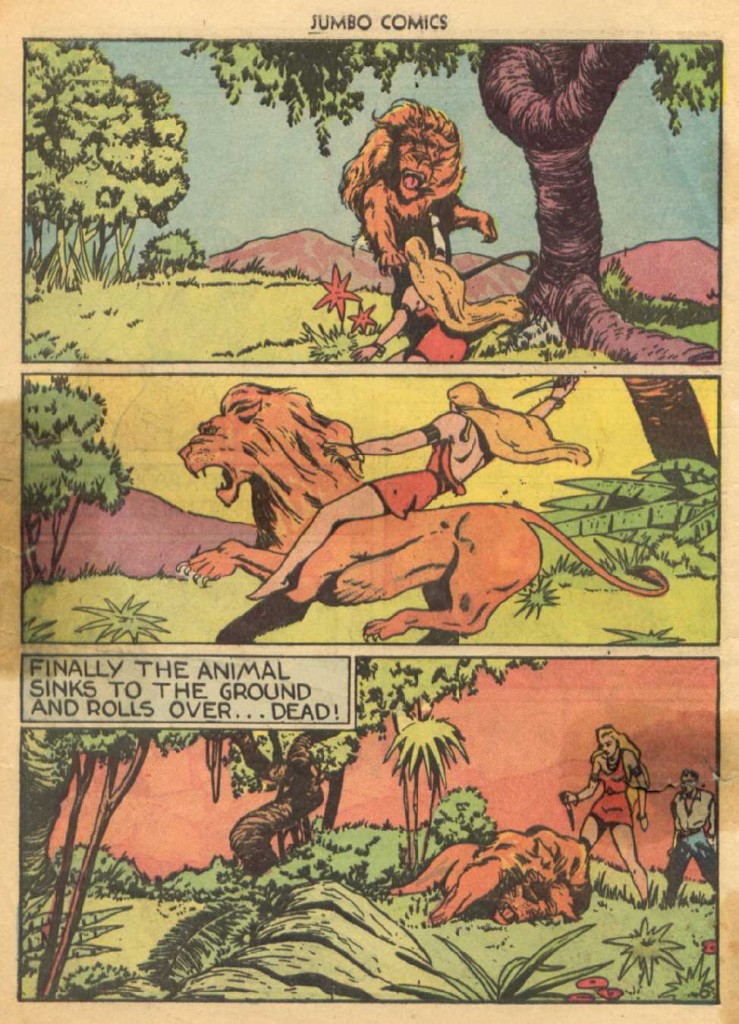

But it would be a mistake to assume that Sheena was a female Amazon brute. Despite the lack of civilized amenities in native surroundings, she was a lovely and completely feminine woman. She always appeared well-groomed in her leopard-skin covering, and her long golden hair was always freshly combed and appeared hygienically clean. Her survival skills were based on her innate intelligence plus her extraordinary agility.

* * *

Sheena spoke perfect English and all the native dialects of central Africa. In addition, she fought with wild animals, outwitted evil men, and escaped innumerable traps that were sprung on her. In spite of these seeming incongruities, Sheena was fully accepted by comics fans, who cheerfully suspended their powers of disbelief in her favor.

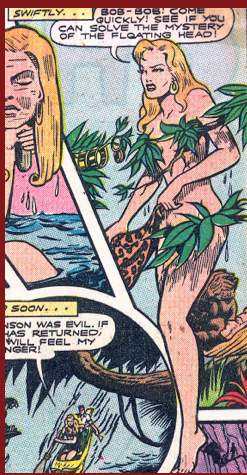

The Jungle Queen slowly built her following. Among the readers who purchased Jumbo Comics on a regular basis was a corps of dedicated Sheena fans. With the release of Jumbo #8, the decision had been made to cut the magazine down to standard comic book size (about 7H” x 10″ at that time) and to print it in full color, to make it more competitive with other commercial comics.

In short, Sheena was a hit. And while she owes her origins to literary giants whose classic prose gave birth to her basic mythos and to creators that went on to great literary successes in the field of comics (especially Eisner with his work with the Spirit and a Contract with God), the predominant view is that Sheena’s popularity stems from one simple concept: Sex sells.

Les Daniels, in Comix, A History of Comic Books in America, summarizes the concept as follows:

What distinguishes [Sheena] was neither the plotting, which was painfully simplistic, nor the dialogue, which became ludicrously stilted in its attempts to achieve a lofty tone. The Appeal was primarily visual, embodied in the alluring figure of the jungle queen herself. On the comparatively innocent level of the pin up art of the forties, she had sex appeal.

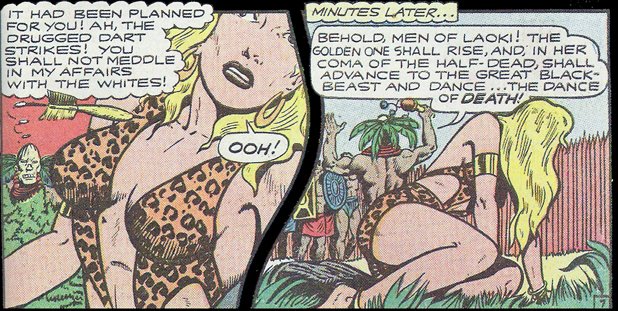

Recently, I described the origins behind the creation of Wonder Woman. Basically, the psychologist William Moulton Marston created Wonder Woman to serve as an empowering role model for young girls. There were no such lofty aspirations behind the creation of Sheena. She was written and drawn to entice male readers and would epitomize what would later be dubbed “good-girl art” by David T. Alexander. Basically, good girl art features an attractive young woman, usually in skimpy form-fitting clothing, standing in a provocative pose for no reason related to the story. Fiction House, specialized in Good Girl art within the pages of their Wings Comics, Rangers Comics, and Fight Comics Ron Goulart writes in Great History of Comic Books (1986),

In [Fiction House] stories, you encountered amply constructed and sparsely clad young women on the land, on the sea, and in the air. Deep into the jungles, you ran into beautiful blondes wearing leopard skin undies; off on some remote planet there would be a lovely redhead sporting a chrome-plated bra.

And while Fiction House had other pin ups, Sheena was the queen of the good girls. Sheena appears in the first 10 issues of Jumbo Comics (eight which were in black and white) wears a normal dress. However, in issue ten, Sheena faces off against Namu the killer-lion and a leopard. At the end of the story, she replaces her normal dress with the leopard’s skin. Interestingly, after this change, Sheena is featured on more covers.

Bradford Wright, in his book Comic Book Nation charges:

No publisher, however, played to male libidos more frequently or effectively than Fiction House. Women with short skirts, long slender legs, and exaggerated breasts adorned the covers of Fiction House’s comic books, while the stories prepared for the publisher by the Iger shop (where much of the material, interestingly, was written by women) beckoned randy young males with sexually suggestive and sadomasochistic images.

And Michael Schumaker applies this to Sheena in his book:

As scantily clad as her male counterpart [Tarzan], Sheena took on man and beast in a series of dreams for teenage boys, a combination of adolescent pinup and action story, and it didn’t seem to matter that this young woman, born in the deepest Africa, always had perfectly cut and brushed blonde hair, spoke textbook English and wore outfits, albeit leopard skin ones, that seemed to be designed by a Hollywood tailor. Sheena was a creation on demand and definitely not the type of character Eisner would have preferred to deal with, but he wasn’t about to turn down work, either.

Mike Madrid expands on the Sheena’s good girl style in his book Supergirls, Fashion, Feminism, Fantasy, and the History of Comic Book Heroines:

Sheena was drawn in provocative poses that best showed off her ample breasts carefully concealed by strategically placed leopard skin. Long shapely legs broke out of panel borders in High Baroque style to arch across the page. Sheena swung from vines or leapt across the page, prominently showing off a spotted rump or widely spread legs. Her long blonde hair was wild and free flowing. Stories mixed shades of Eros and Thanatos by showing the erotically drawn Sheena locked in combat with a wild snarling beast, or writhing in the tentacles of a giant squid. Sheena was the untamed fantasy, the wild sensual creature that was not confined by polite society’s idea of how a woman should dress or act.

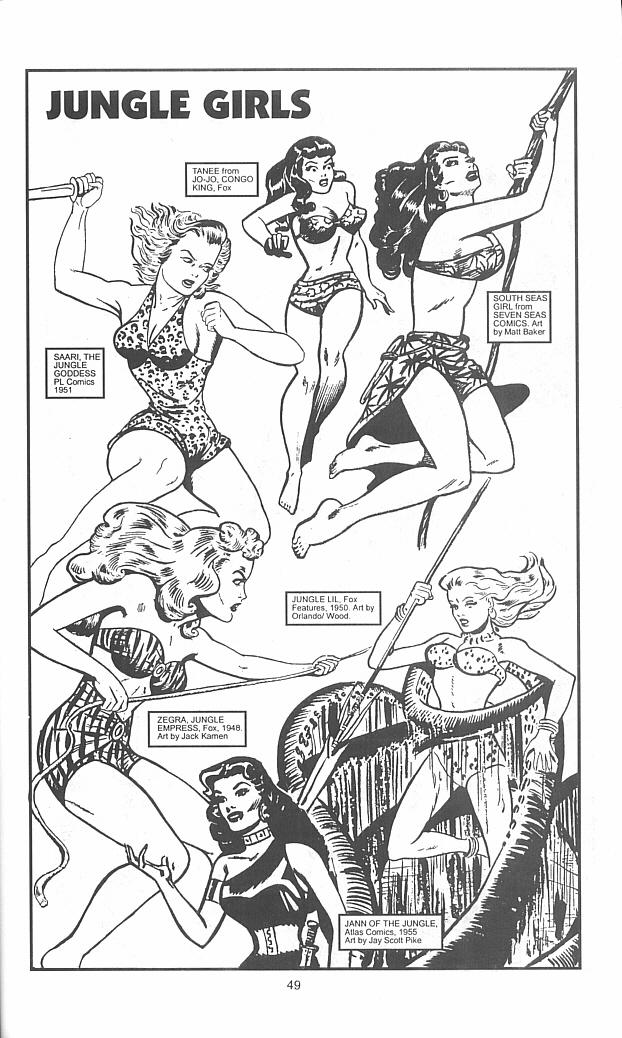

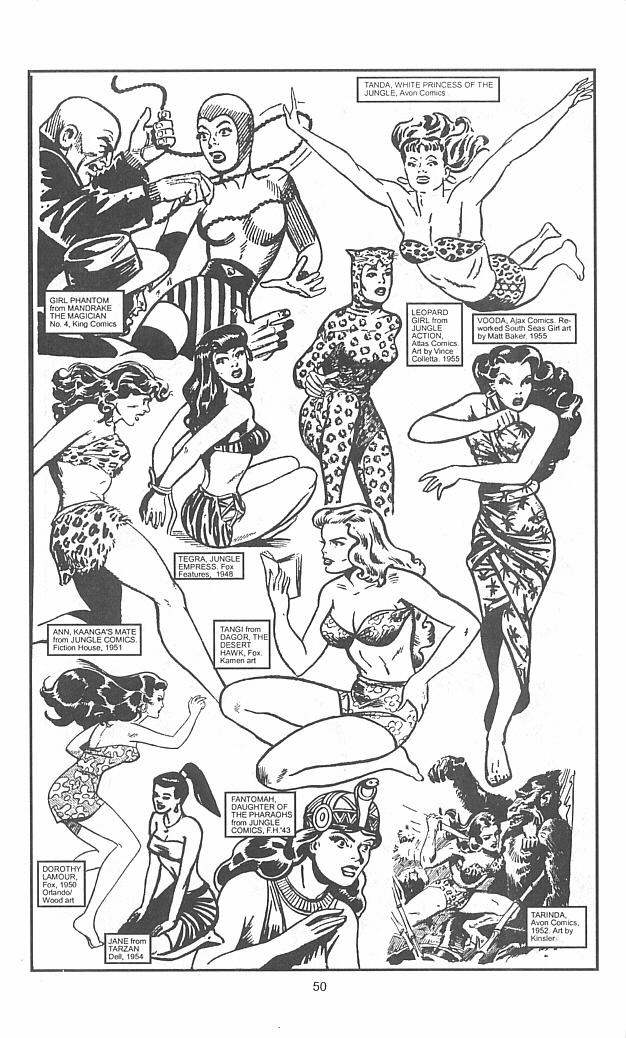

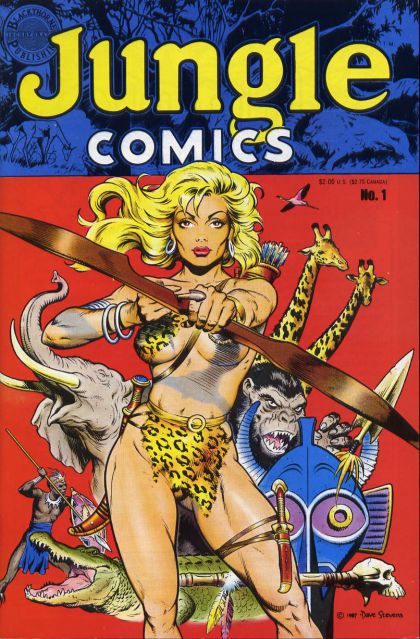

Of course, the success of Sheena meant that there were numerous copycat jungle girls, many from Fiction House. In the world of pre-code comics, there was Ann Mason (the mate of Kaanga) from Jungle Comics (Fiction House). Ann started out dressed casually, but apparently met Sheena’s tailor and started sporting an identical leopard skin dress. In Issue 8, she was replaced by Jessie, another mate of Kaanga. Camilla (also from Jungle Comics) wore zebra skin. Fiction House also featured Fantomah (Jungle Comics), who is the first superheroine with powers; Princess Taj (Jungle Comics), who rode an elephant; and Tiger Girl and Princess Vishnu (Fight Comics). Other companies also joined in on the Jungle Girl market with: Marga the Panther Woman (Science Comics/Fox); Blanda (Miracle Comics/Hilman); Zara (Mystic Comics/Marvel); Kazanda (Australian Comics); Jun-Gal (Blazing Comics/Rural Home); Kara Jungle Princess and Judy of the Jungle (Exciting Comics/Nedor); Jano, mate of Voodah (Crown Comics/McCombs); Nyoka, the Jungle Girl (Fawcett); South Seas Girl (Seven Seas Comics/Leader Enterprises); Princess Pantha (Thrilling Comics/AC Comics); Tygra of the flame people (Startling Comics/Nedor); Juanda, Tanee, Gwenna, Lura, and Safra, Jo-Jo’s mates (Jo-Jo Jungle King/Fox) (Jo-Jo apparently got around); Tangi (Dagar, Desert Hawk/Fox); Rulah, the Jungle Goddess (Fox); Tegra (the red head) who inexplicably became Zegra (the blonde) (Fox); Taanda, White Princess of the Jungle (later known as Tarinda) (Avon); Saari, the Jungle Goddess (Pl Publishing); Even Sheena’s pulp and movie progenitors would eventually follow her into the comics with: Rima, the Jungle Girl (DC); Jane Porter (Tarzan/Dell); and even Dorothy Lamour, Jungle Princess (Fox). Needless to say, by 1954, the jungle queen market had become quite saturated, much to the delight of male readers.

William W. Savage, Jr, in Commies, Cowboys, and Jungle Queens points out that:

The jungle queens were primarily there for cheesecake, as were many other women. They catered to what passed for prurient interest among adolescent male readers, and sometimes they posed prettily for an older audience of servicemen. They reflected male criteria for the ideal woman: long hair, long legs, large breasts, physical agility, and proclivities rather more emotional than intellectual.

In addition to sexism, Sheena and her progeny have also been accused of fostering racism, imperialism, and colonialism. Wright points out:

When this sort of [good girl art] appeared in Fiction House’s ubiquitous jungle comics, the results took on powerful racist and imperialist—as well as sadomasochistic—overtones. Throughout the post-war era, the jungle formula essentially remained what it had been before World War II: white lords, kings, queens and princesses ruled over jungles populated by childlike, superstitious, and mischievous brown people in need of paternalistic guidance.

Savage adds:

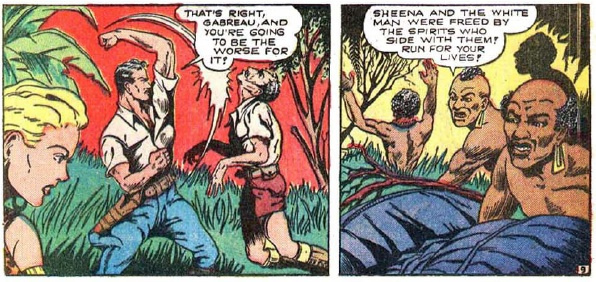

Virtually every story chronicling the adventures of a white ruler of the jungle demonstrated several things about black Africans. They were incapable of self-rule, for instance. Left to their own devices, they inevitably got into trouble by selecting a rotten chief or falling for the fake pronouncements of some false god fobbed on them by a devious shaman. Whenever such things happened, the Africans proved congenitally unable to rectify the situation, coming to depend on the good offices of a bikini-clad white hero or heroine who was always bigger, smarter, stronger, and possessed of greater stamina and agility than any native and all wildlife.. . . . It was as if each jungle lord or lady presided over a vast nursery filled with dark children who were often disobedient and sometimes rebellious, but always lovable, in the end, generally tractable—except for the few who had to be killed in order to save the rest.

Wright provides some specific examples of this in Comic Book Nation. In the first, Sheena orders an African tribe to abolish their “cruel burial customs.” Rather than argue for their beliefs, the tribal chief simply responds, “We hear, O Sheena, we obey!” In another, Sheena deposes an evil leader of the elephant tribe and chooses a new ruler for the people. In response, the African natives similarly grovel before her and chant, “We hear! We obey, O Sheena!” In the final example, Wright states:

The powerful racial anxieties underlying such material are hardly more evident than in one particular episode of Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. The story, set in French West Africa, opens with an African nationalist king uniting scattered tribes into “a single ferocious unit, sworn to drive the white man from the country!” One of the savage tribesmen attacks Sheena and her male companion, crying, “Me now kill them! Show all chiefs, me big ruler . . . Kill all white people!” Sheena and her contingent of loyalist natives defeat the rebellion and preserve white colonial rule. For this, she is awarded a medal of valor from the French government.

What is so interesting about this is that the post war jungle comics, or any comic published in the same time frame for that matter, did not fully represent what was actually happening in America. During this period, there was renewed interest in civil rights. The army became integrated, and in Brown v. the Board of Education, the Supreme Court (with Dr. Wertham’s help) determined that separate was not equal. Of course, you would never know this if you reading comics because the only black people in comics were either comic relief stereotypes in America or potential victims in Africa.

Of course, Sheena also has her defenders. Doug Mann writes in an article entitled, A Primordial Rumble in the Comic Book Jungle: Sheena Rehabilitated (available at http://publish.uwo.ca/~dmann/Sheena/Sheena%20Rehabilitated.htm)

But her fiercest enemies were not ravenous lions or evil slavers, but critics from Fredric Wertham in the 1950s to Bradford Wright in the new millennium, who attacked her adventures as being too sexy and too violent, charging her with sexism, imperialism and racism. A careful study of both the covers and the stories from Jumbo Comics and Sheena from 1940-1953 will show that although she’s certainly a violent and sexy heroine, she is largely innocent of two of these charges, and only partly guilty of the third.

After a thorough analysis of covers, storyline and the different phases of the character’s development, Mann concludes:

A fair court of comic-book critique will find the post-1940 Sheena innocent of these two charges, and guilty of the third, racism, to a much lesser degree than her accusers have suggested.

Despite this, the predominant view of the Sheena stories can be summed up by Editor Steven Christy, when he states in the introduction to Volume One of The Best of Golden Age Sheena (Devils Due Publishing):

No doubt you will have noticed that the preceding 100 pages of stories are filled with racist, sexist, and colonialist propaganda and hoo-ha. … Sheena was always a comic that reveled in its no-holds barred, politically incorrect pulpy roots.

So, given this view, it shouldn’t be surprising to see that the Jungle Girls came under fire in the Comic Book Scare of the 1950s. Fredric Wertham had a particular disdain for jungle girl comics. As Steven E. De Souza writes, in the introduction to Sheena: Queen of the Jungle Vol. 2:

But of all her adversaries, one particular “Man-Men” was the most relentless: psychiatrist Fredric Wertheim [sic], M.D. . . . . in the Seduction of the Innocent, the bestseller that alarmed the nation, he described the appeal of Sheena and her ilk as nothing less than “torture, bloodshed, and lust in an exotic setting!”

And Mike Madrid wrote:

In the end, it was the very sex appeal that made Sheena a star that proved to be her undoing. As the 1940s drew to a close, tastes were changing. By 1954, Dr. Fredric Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent had alarmed America with the idea that comic books might be corrupting the youth of the nation. Drawing particular fire as the violence and highly sexualized imagery featured in many of the more lurid comic books.

In Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics, Amy Kiste Nyberg adds that Wertham had additional issues with the jungle comics:

While Wertham’s main concern was violence, he also studied the way race and gender were depicted in comic hooks. In a discussion of the “jungle” comic books, Wertham wrote that while the white people in these comics were blond, athletic, and shapely, the natives were usually portrayed as subhuman or even ape-like. Such portrayals, where the heroes were always “blond Nordic supermen,” made a deep impression on children. Wertham noted that such images acted to reinforce attitudes of prejudice at the individual level, but they also worked at the broader social level, labeling as “minorities” what really constituted “the majority of mankind” (too). Children, he argued, were presented with two kinds of people: one is the tall, blond, regular-featured man or pretty young blonde girl, and the others fall into the broad category of inferior people. The social meaning attached to such representations becomes clear, according to Wertham, when children are asked to identify the villain in a story and invariably choose the character who is nonwhite, of an identifiable ethnic background, or one who in some other way deviates from the norm. Children take for granted these standards about race in other words, such representations become normalized. And where nudity was found in comics, it was generally nonwhite women who are portrayed this way. Noted Wertham: “It is probably one of the most sinister methods of suggesting that races are fundamentally different with regard to moral values, and that one is inferior to the other.

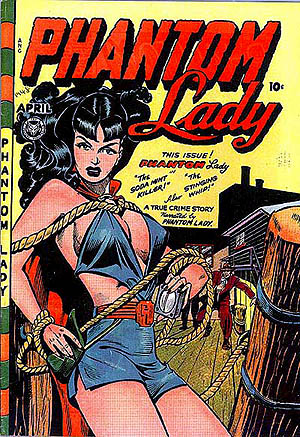

Of course, Fiction House was a specific target of Wertham in Seduction of the Innocent, which singled out the cover of Fiction House’s Phantom Lady No. 17 as glorifying bondage. Les Daniels writes,

Of course, Fiction House was a specific target of Wertham in Seduction of the Innocent, which singled out the cover of Fiction House’s Phantom Lady No. 17 as glorifying bondage. Les Daniels writes,

Sad to say, [EC and crime comic publishers] were not the only ones that were washed overboard in the Doctor’s teapot tempest. Other idylls that sank in the storm included those bastions of pulp fantasy, Fiction House and Quality Comics. Lost beneath waves of indignation were such mighty creations like . . . Sheena, Queen of the Jungle.

Moreover, the industry formed Comics Code Authority in response to public backlash, and it was implemented specifically as a result of publishers’ concerns about government regulation. The industry formed a self-regulatory body, which would impose and self-police a “code of ethics and standards” for comics. This was done by requiring that each comic book published have a seal of approval. As expected, like crime and horror comics, jungle girl comics did not fare well under the Code as several of its basic requirements directly applied (and some appear as if they were were written with jungle girls, like Sheena, in mind), including:

CODE FOR EDITORIAL MATTER

General standards—Part A

(7) Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive and unnecessary knife and gunplay, physical agony, gory and gruesome crime shall be eliminated.

General standards—Part B

(3) All lurid, unsavory, gruesome illustrations shall be eliminated.

(4) Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used or shall be published only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue and in no case shall evil be presented alluringly, nor so as to injure the sensibilities of the reader.

(5) Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited.

General standards—Part C

Religion

(1) Ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible.

.Costume

(1) Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.

(2) Suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture is unacceptable.

(3) All characters shall be depicted in dress reasonably acceptable to society.

(4) Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities.

NOTE.—It should be recognized that all prohibitions dealing with costume, dialog, or artwork applies as specifically to the cover of a comic magazine as they do to the contents.

Marriage and Sex

(2) Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at nor portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

(4) The treatment of live-romance stories shall emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.

(5) Passion or romantic interest shall never be treated in such a way as to stimulate the lower and baser emotions.

(6) Seduction and rape shall never be shown or suggested.

(7) Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden

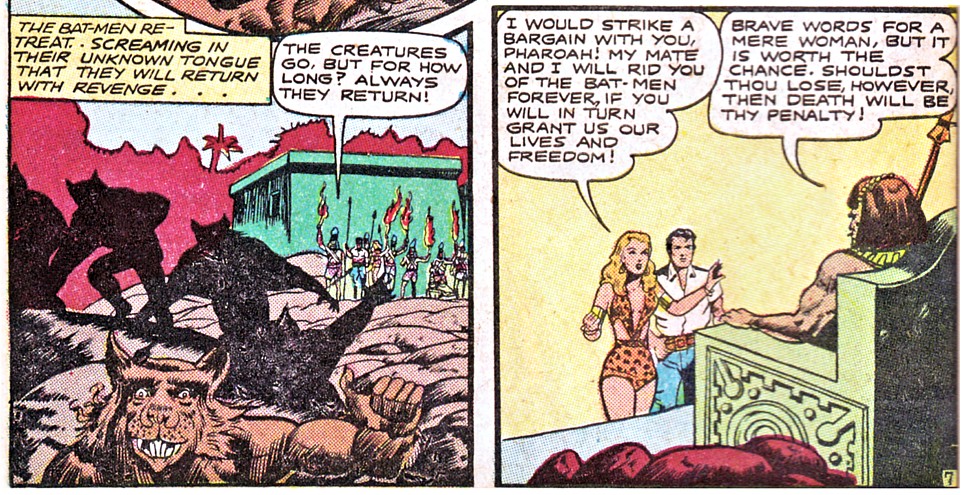

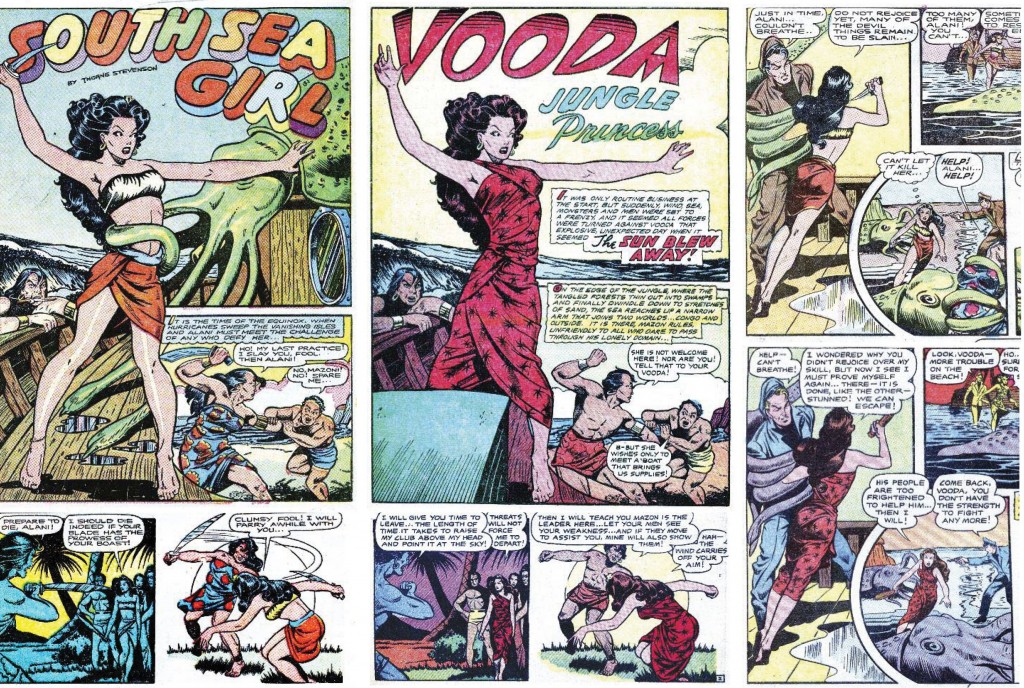

As a result, the Jungle Girl stories were forced to change drastically after the CCA. An example of this can be found in Alter Ego #105, which features a before and after the Code comparison of Voodo/Vooda, they explain:

When the Ajax-Farrell horror title Voodoo became Vooda and starred a Sheena wanna-be, it reprinted stories from the Universal Phoenix Features (i.e., Iger Studios) title South Seas Comics—but it had to alter them to fit the Code. Compare the “cover-up” between the splash pages from SSC #5 (Aug. 1946) and Vooda #22 (Aug. 1955, actually the third issue as Vooda)—followed by, clockwise from top right, the changes in both weaponry and additional, explicatory, less sanguinary dialogue from those two issues—plus, during a knife/no-knife fight, Vooda’s stocky female opponent becomes a male!

Given that Fiction House books were all based on the popularity of Good Girl art, the Code put them out of business. Fiction House’s last book was Jungle Comics #163.

But, truth be told, while Seduction of the Innocent and the Comics Code greatly affected her rivals, neither really had anything directly to do with the demise of Sheena. This is because Fiction House cancelled Jumbo Comics before the creation of the Code. In fact, the last issue of Jumbo Comics was published in April 1953, which means it also predates the publication of Seduction of the Innocent (1954).

That being said, Sheena was certainly affected by the crusading critiques of comics from Wertham, Sterling North, and Gershon Legman. Beginning in issue 127, there is an obvious effort to deemphasize the sex and violence in Sheena. Her costume transforms into a conservative one piece pelt suit. Sheena also would rather talk than fight and many of these later issues are full of very wordy captions and preachy word balloons. In short, Sheena became a pretty boring character.

Madrid explains:

Fiction House tried doctoring up Sheena’s old stories to reduce the violence and amount of flesh on display, but eventually cut its losses and got out of the comics business in 1954 . . . Sheena’s last swing through the trees was in a 3-D comic released in 1953. With Fiction House’s retreat from the comic world, Sheena disappeared from the newsstands . . . .

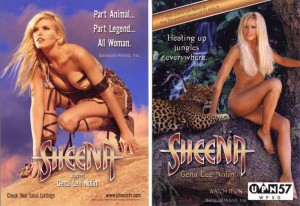

Iger wrote in Alter Ego 21 that, “The only disappointment was that Sheena alone couldn’t reverse the fortunes of Fiction House, and the company soon went out of business.” Sadly, Sheena would not resurface in the comics for several decades (there was an illegal knockoff published in1958 by I.W. Publications, but I’m not sure it counts), but that doesn’t mean the Jungle Queen was beaten. Considered too edgy for comics, Sheena just changed mediums. In 1955, the first comic heroine also became one of the first heroines on television. The show featured Irish McCalla as Sheena and lasted for 26 episodes. (The producers also edited together three episodes of that series into a feature called Queen of the Jungle, which received minimal cinema release in the US and Europe in the late Fifties.) Thirty years later, in 1984, Columbia Pictures released Sheena, starring Tanya Roberts. The movie was not a critical or commercial success. (On the bright side, it took home the Razzies for Worst Screenplay, Worst Musical Score, Worst Actress, Worst Director, and Worst Picture). Sixteen years later, in October, 2000, Sheena returned to the small screen for a 35 episode run. This time, the queen was portrayed by Gena Lee Nolin. Nolin’s Sheena was also superpowered and had the ability to adopt the form of any warm-blooded animal once she gazed into its eyes. She was also depicted as a ferocious killer, capable of becoming a humanoid creature called the Darak’Na. Finally, Galaxy Publishing, Inc. launched an animated Sheena series on the Web in 2009.

Still, readers did not really have time to miss Sheena since her absent throne was taken by far-too-many-to-name replacement Jungle Girls. Most notably, Marvel created a Sheena-like character named Shanna, the She Devil who debuted in December 1972 in her own self-titled book. It is clear that Shanna follows in the footsteps of Sheena (Marvel even changed her hair color to blonde thus making the two characters even more similar). Unlike Sheena, who lived in a self-imposed comic’s exile, Shanna continued to make numerous appearances through the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s. An alternate version revamp appeared in 2005 drawn by good girl artist Frank Cho, (who also revamped Jungle Girl, another Sheena-type character created by Hanna Barbera). Apparently, the series was originally scheduled for release under Marvel’s “mature readers” MAX imprint but was reworked, with Cho eliminating the nudity before publication. A four-issue sequel miniseries was also released, Shanna, The She-Devil: Survival of the Fittest by Justin Gray and Jimmy Palmiotti and Khari Evans. Shanna has most recently appeared in the Marvel Now Savage Wolverine title also drawn by Cho. DC tried the same thing with Sheena’s pulp predecessor, Rima the Jungle Girl, with less success.

Still, readers did not really have time to miss Sheena since her absent throne was taken by far-too-many-to-name replacement Jungle Girls. Most notably, Marvel created a Sheena-like character named Shanna, the She Devil who debuted in December 1972 in her own self-titled book. It is clear that Shanna follows in the footsteps of Sheena (Marvel even changed her hair color to blonde thus making the two characters even more similar). Unlike Sheena, who lived in a self-imposed comic’s exile, Shanna continued to make numerous appearances through the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s. An alternate version revamp appeared in 2005 drawn by good girl artist Frank Cho, (who also revamped Jungle Girl, another Sheena-type character created by Hanna Barbera). Apparently, the series was originally scheduled for release under Marvel’s “mature readers” MAX imprint but was reworked, with Cho eliminating the nudity before publication. A four-issue sequel miniseries was also released, Shanna, The She-Devil: Survival of the Fittest by Justin Gray and Jimmy Palmiotti and Khari Evans. Shanna has most recently appeared in the Marvel Now Savage Wolverine title also drawn by Cho. DC tried the same thing with Sheena’s pulp predecessor, Rima the Jungle Girl, with less success.

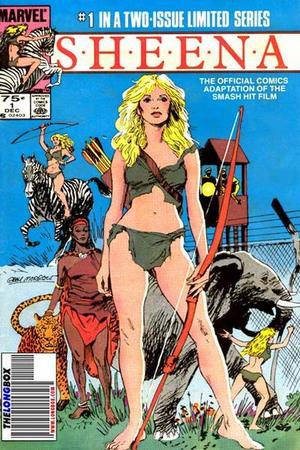

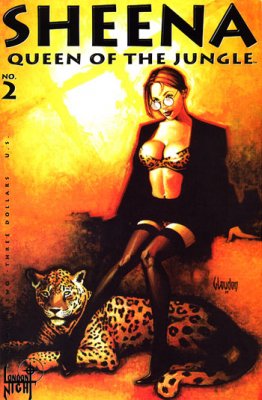

Of course, while the pretenders survived, Sheena’s return to comics has hit a few bumps in the road. In the 1970s, SkyWald published a reprint of one of Sheena’s stories. Sheena next appeared in 1984 from Marvel Comics in an adaptation of the “award”-winning Tanya Robert’s film, thus causing even more Shanna/Sheena confusion. Around that same time, Blackthorne began publishing reprints as well as new stories featuring Sheena. Unfortunately, they did not own the license, which is always a bad thing. A licensed version was eventually released in 1998 from London Night Studios, although it barely resembled the original character (Sheena was a red haired environmentalist leader of a band of academics).

Finally, in 2007, Devil’s Due Publishing acquired the license and returned Sheena to her roots (and I don’t just mean her blonde hair). Timothy Straub explains in Sheena 101 (printed in Sheena Queen of the Jungle Vol. 1):

Finally, in 2007, Devil’s Due Publishing acquired the license and returned Sheena to her roots (and I don’t just mean her blonde hair). Timothy Straub explains in Sheena 101 (printed in Sheena Queen of the Jungle Vol. 1):

In the meantime, aside from a few moderately notable exceptions, Sheena, Queen of the Jungle has been conspicuously absent from the pages of the medium in which she first matured. But, in the Spring of 2007, Devils Due Publishing, Galaxy Entertainment, screenwriter Steven E. de Souza, and the team of Robert Rodi and Matt Merhoff are prepared to change that. While there have been other comic heroines clad in animal skin and posed in the blotched shade of the underground, those were merely pretenders to the throne. It is well past time for the Queen of the Jungle to return to prowl her domain.

So, looking back, one might ask why I bothered with this topic. The comic books of the Golden Age represented little more than escapism for millions of readers. And viewing this as the goal, Sheena certainly succeeded on many levels. However, unlike other characters that came under fire in the ’50s, such as role models like Superman and Wonder Woman, Sheena and her fellow Jungle Girls were pretty much guilty of the charges leveled at them. Sheena’s jungle adventures really didn’t really give much back to society. In fact, viewed through the lens of hindsight, it is pretty clear that these comics contain sexism, imperialism, racism, and pretty much any other evil -ism you can think of. But that is the beauty of art and free speech: You don’t have to agree with it, or even like it, to respect it. And Sheena should be protected.

Her early adventures provide us with a glimpse of our past, and not necessarily in a good way. Still, despite the fact that Sheena was a glorified pin up girl, she also was arguably one of the strongest female characters of her time. Not only did Sheena feature an interesting role reversal in the typical damsel in distress story, but she paved the way for other heroines to appear in their own stories, to star in their own books, and to expand into other mediums.

Sadly, Sheena nearly became extinct. But, it was not the lions, tiger, or bears that almost killed the Queen of the Jungle. No, her fall came at the hands of the same creature that wiped out so many of those animals on the wall at the National Zoo. Her attackers were well-meaning people.

Thankfully, the jungle queen was not only saved from extinction, but thrives in the current comics world to help provide some good old fashion escapism in an otherwise harsh world.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net