Every once in a while, some blogger or columnist garners a lot of pageviews by rekindling the simmering debate as to whether Young Adult fiction has become “too dark.” Two years ago, for example, this hand-wringing column from the Wall Street Journal inspired a Twitter backlash under the hashtag #YAsaves, where devoted readers testified to the positive impact that Young Adult books — including and often especially the “dark” ones — had on their lives. Earlier this month, children’s author Shoo Rayner dredged up the debate once again with a blog post about the “morally corrupt” books that the Youth of Today are reading.

Every once in a while, some blogger or columnist garners a lot of pageviews by rekindling the simmering debate as to whether Young Adult fiction has become “too dark.” Two years ago, for example, this hand-wringing column from the Wall Street Journal inspired a Twitter backlash under the hashtag #YAsaves, where devoted readers testified to the positive impact that Young Adult books — including and often especially the “dark” ones — had on their lives. Earlier this month, children’s author Shoo Rayner dredged up the debate once again with a blog post about the “morally corrupt” books that the Youth of Today are reading.

Seemingly unaware that he was invoking an argument that’s been attempted and discredited at least since the invention of the novel, Rayner suggested that impressionable readers of Young Adult fiction might become hardened to violence and begin to engage in it themselves:

Why are we no longer surprised when kids join gangs and shoot each other on the streets? They’re conditioned to it by playing killing games on their consoles and watching endless serial killer stuff on TV. So why not in children’s books too? How else are publishers going to compete and make a buck other than by joining in the slow moral decline? We are conditioning ourselves to accept that it’s okay for kids to kill each other.

This is virtually identical to the arguments that were advanced against crime and horror comics in the early 1950s. Unfortunately, those arguments were given credence by Congress, which devoted three days of hearings about the possible influence of comics on juvenile delinquency. Although no federal legislation resulted, the nationwide attitude of adults towards comics remained so hostile that the industry founded the Comics Code Authority in a last-ditch attempt at self-preservation. While most superhero comics lauding Truth, Justice, and the American Way could negotiate the new rules without too much loss of interest, the thrillingly lurid crime and horror genres simply could not. By the end of the decade, they were all gone.

Happily, today there are many more adults eager to refute arguments like Rayner’s. In a post that’s been published at Book Riot and later The Huffington Post, librarian and author Kelly Jensen analyzes just what it is about Young Adult fiction that so disturbs some adults:

Some grown-ups are afraid of context.

It’s clear not only in their claims about what it is YA books are promoting but also in their strong stances that YA books were never as “bad” in their day.

Of course they were.

The difference is that back in their teen days, the context was different. They were teens themselves! The context was living, breathing, and experiencing the hard truths and sharp edges that come with navigating adolescence in the moment. The context was discovering that sometimes bad things happen to people or the realization that grown-ups are flawed creatures. That sometimes — more than sometimes — the world is a cruel and unforgiving place, no matter how much you play by the rules.

Many adults profess to believe that Young Adult books dealing with topics such as sex, violence, bullying, drugs and alcohol, rape and abuse, or suicide and self-harm encourage those behaviors rather than simply reflect their existence in the lives of many teens. Trying to protect youth by condemning or even banning books does nothing to change this reality, says Jensen:

Challenging the books doesn’t change the teen years.

These challenges are instead reminders that adults want to shield teens from their own contextual experiences. Because when you take away the books that are problematic, you are also able to take away rape, violence, gangs, sex, and every other scary trigger that is part and parcel of the lives of teens today (and the lives of teens in the past).

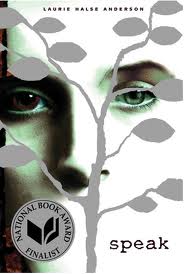

This truth has also been affirmed by Young Adult authors themselves, who frequently hear from teens who have been helped — often literally saved — by their books. Like Laurie Halse Anderson, author of frequently-challenged Speak:

My book gave [survivors of sexual assault] the courage to speak up. These readers saw themselves in Melinda. They walked in her footsteps and for the first time, found their voice. They wrote me letters and e-mail. They slipped notes into my hand when I visited their school. They walk up to me at book signings, tears puddling. After a quiet conversation, there is a lot of hugging. (This is why I always have a box of tissues next to the pens at my book signings!)

Or Stephen Chbosky, whose The Perks of Being a Wallflower was just challenged again:

Part of the reason why Perks connects with so many kids is because it’s real. It’s comforting, because the situations described in the book are so universal and happen to so many teenagers, but it seems like the people who challenge the book don’t want to admit these things happen.

Or Sherman Alexie, the author of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, who recalls when he was a teen and adults tried to shield him from books, movies and music dealing with things he’d already experienced in real life:

They wanted to protect me from sex when I had already been raped. They wanted to protect me from evil though a future serial killer had already abused me. They wanted me to profess my love for God without considering that I was the child and grandchild of men and women who’d been sexually and physically abused by generations of clergy.

What was my immature, childish response to those would-be saviors?

‘Wow, you are way, way too late.’

Despite such wrenching testimonies as to the value of dealing honestly with difficult and/or “grown-up” topics in books for teens, it seems there will always be a certain segment of adults like Rayner whose first impulse is to condemn the books and try to take them away from those who need them most. This is why CBLDF and other anti-censorship organizations are so often compelled to defend literature for and about teens in particular, and we are always heartened to see impassioned arguments for teens’ right to read from adults like Jensen and the YA authors quoted here, from teachers who witness the effect of literature on their students, and especially from teens themselves.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.