Happy Women’s History Month! All through March, we’ll be celebrating women who changed free expression in comics. This week we spotlight some creators whose work has been most frequently banned and challenged, plus a few who started out in the Pre-Code Era.

Follow our Tumblr every weekday for biographical snippets on female creators who have changed the face of free expression in comics by pushing the boundaries of the medium and/or seen their work challenged or banned. We’re also collecting the posts here on a weekly basis.

Jillian and Mariko Tamaki

Canadian cousins Jillian and Mariko Tamaki both came to graphic novels somewhat unconventionally: Jillian started out (and continues) as a freelance illustrator for books and periodicals including the New York Times, Esquire and the New Yorker, while Mariko cut her teeth in the performance art and comedy scenes of Montreal and Toronto. Growing up on opposite sides of the country—Jillian in Calgary and Mariko in Toronto—they both evinced a rebellious streak in their teen years. Mariko in particular experienced alienation from her peers as “a weird, freaky, gothy kid” at an elite private boarding school, while Jillian attended public school and says she and her friends were also “disaffected, kinda gothy – they called us ‘the dirties’ in high school.”

Canadian cousins Jillian and Mariko Tamaki both came to graphic novels somewhat unconventionally: Jillian started out (and continues) as a freelance illustrator for books and periodicals including the New York Times, Esquire and the New Yorker, while Mariko cut her teeth in the performance art and comedy scenes of Montreal and Toronto. Growing up on opposite sides of the country—Jillian in Calgary and Mariko in Toronto—they both evinced a rebellious streak in their teen years. Mariko in particular experienced alienation from her peers as “a weird, freaky, gothy kid” at an elite private boarding school, while Jillian attended public school and says she and her friends were also “disaffected, kinda gothy – they called us ‘the dirties’ in high school.”

Both cousins were well-established in their creative careers before they struck upon the idea of collaborating. Mariko was offered the chance to publish some of her stage monologues in comic form, as part of a zine series that Jillian says aimed “to pair people who had never written a comic and people who had never drawn a comic.” Mariko naturally thought of her illustrator cousin, and together they produced a 24-page comic which would later expand into the 2008 graphic novel Skim. Loosely inspired by Mariko’s boarding school misfit experience, it became the first graphic novel nominated for a prestigious Governor General’s Award—but only in the “text” category, which prompted several comics creators to issue an open letter arguing that neither the text nor the illustrations are meant to stand alone in this format, and both Tamakis should have been nominated.

Although the selective nomination put both Jillian and Mariko in an awkward public situation, it apparently didn’t harm their collaborative relationship. In 2013 they issued This One Summer, a coming-of-age story of adolescent friends Rose and Windy. This time the book was nominated for Governor General’s Awards for both text and illustration, and won in the illustration category. It also broke another barrier in the U.S., where it was the first graphic novel to make the shortlist for the American Library Association’s Caldecott Medal. It was also shortlisted for ALA’s Printz Award for Young Adult literature, which previously went to Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese in 2007. The Caldecott Honor has led to some rather unexpected backlash, however, as adults who think of that award as the domain of purely innocent picture books blame This One Summer for being other than they expected. Since the honor was announced last month, CBLDF has been confidentially involved in monitoring challenges to the book in various communities—which is why we put together a resource for teachers and librarians who may need to defend its presence in their collections or curricula.

—Contributing Editor Maren Williams

Raina Telgemeier

Growing up in San Francisco, Raina Telgemeier was an avid fan of newspaper comics from an early age. She particularly enjoyed Calvin and Hobbes and For Better or For Worse, and passed many hours in childhood creating her own strips and mini-comics. After she graduated from New York’s School of Visual Arts in 2002 with a B.F.A. in illustration, Scholastic offered her the opportunity to take on another childhood favorite: Ann M. Martin’s The Baby-Sitters Club series. Telgemeier adapted four of the books as graphic novels, introducing them to a new generation of readers.

Growing up in San Francisco, Raina Telgemeier was an avid fan of newspaper comics from an early age. She particularly enjoyed Calvin and Hobbes and For Better or For Worse, and passed many hours in childhood creating her own strips and mini-comics. After she graduated from New York’s School of Visual Arts in 2002 with a B.F.A. in illustration, Scholastic offered her the opportunity to take on another childhood favorite: Ann M. Martin’s The Baby-Sitters Club series. Telgemeier adapted four of the books as graphic novels, introducing them to a new generation of readers.

With her 2010 graphic novel Smile, Telgemeier moved into the realm of memoir, chronicling the painful period after she knocked out her front teeth as a young teen and had to undergo several rounds of oral surgery and orthodontia. To make matters worse, Telgemeier’s gap-toothed smile and later mouthful of braces came in for mockery from those she thought were her friends. Sisters, the 2014 sequel to Smile, delves into Telgemeier’s initial rivalry with her younger sister Amara and their later rapprochement as their parents’ marriage began to dissolve.

In between the two memoirs in 2012, Telgemeier produced the fictionalized graphic novel Drama, which recounts the joys and tribulations of a middle school theater troupe. Although most readers of all ages found it to be just as endearing and authentic as Telgemeier’s other books, a small but vocal minority have objected to the inclusion of two gay characters, one of whom shares a chaste on-stage kiss with another boy. Negative online reader reviews have accused Telgemeier of literally hiding an agenda inside brightly-colored, tween-friendly covers, but in an interview with TeenReads she said that while she and her editors at Scholastic were very careful to make the book age-appropriate, they never considered omitting the gay characters because “finding your identity, whether gay or straight, is a huge part of middle school.”

—Contributing Editor Maren Williams

Melinda Gebbie

Melinda Gebbie began her career as a fine artist but found a home among the underground comix creators in her birthplace of San Francisco, California. Her first comics work was published in the seminal all-womenunderground comix anthology Wimmen’s Comix, and she published her first solo work in 1977 with the release of Fresca Zizis. The brightly colored, dreamy, and explicit images that graced the 36 pages of Fresca Zizis would eventually catch the eye of UK censors when Knockabout Comics imported 400 copies of the book in 1985. The books were seized by UK customs for pornographic images, and despite Gebbie’s eloquent defense of the book during the subsequent obscenity trial, British authorities ruled that the copies should be confiscated and burned. Possession of the comic remains a crime in the UK today.

Melinda Gebbie began her career as a fine artist but found a home among the underground comix creators in her birthplace of San Francisco, California. Her first comics work was published in the seminal all-womenunderground comix anthology Wimmen’s Comix, and she published her first solo work in 1977 with the release of Fresca Zizis. The brightly colored, dreamy, and explicit images that graced the 36 pages of Fresca Zizis would eventually catch the eye of UK censors when Knockabout Comics imported 400 copies of the book in 1985. The books were seized by UK customs for pornographic images, and despite Gebbie’s eloquent defense of the book during the subsequent obscenity trial, British authorities ruled that the copies should be confiscated and burned. Possession of the comic remains a crime in the UK today.

A brush with UK censors didn’t stop Gebbie from continuing her groundbreaking work. She is best known to many for her labor of love, Lost Girls. Alongside writer Alan Moore, Gebbie sought to create a piece of literate erotica that focused on three central characters: Dorothy Gale (The Wizard of Oz), Wendy Darling (Peter Pan), and Alice Fairchild (Alice in Wonderland). Gebbie and Moore set their story against tumultuous events contemporary with the adult versions of the characters, including the release of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and the start of World War I. Gebbie’s artwork is lush and sensuous, and Gebbie has attributed the 16 years she spent on the three-volume series with expanding her own artistic sensibility and skill.

Many expected that Lost Girls would meet with immediate controversy upon its release, but the book has actually met with little resistance in the United States. While some retailers refuse to carry the book, and it has met resistance in foreign markets (most notably, the UK and New Zealand), Gebbie’s sensitive, colorful, and painterly artwork can be credited in no small part for keeping the work from being labeled obscene.

Gebbie’s work and subject matter may not appeal to everyone, but Gebbie has always sought to depict female sexuality in a positive manner, sometimes to the derision and even overt hostility of male colleagues. During a 2013 talk at the Edinburgh Book Festival, she described some of her opponents: “They were some of the most backward guys in terms of their fears and belief systems, and their sexism. They were classically untrained in the consciousness of appreciating women.” She works to overcome this attitude with her art, and she takes an equally strong stance against censorship, even for material that she doesn’t like, telling Edinburgh attendees, “I don’t think the imagination should ever be policed because it’s in the imagination landscape that we work out some of these crucial issues before we have to act them out on the world stage.”

—Editorial Director Betsy Gomez

Nell Brinkley

Nell Brinkley, often credited as the “Queen of Comics” during her time, was not only one of the pioneering women at the turn of the century who helped shape the fledgling comics industry itself with her innovative and unique style, but with her fresh, young voice she would also usher in a new era for women both on and off the page to openly and freely express themselves.

Nell Brinkley, often credited as the “Queen of Comics” during her time, was not only one of the pioneering women at the turn of the century who helped shape the fledgling comics industry itself with her innovative and unique style, but with her fresh, young voice she would also usher in a new era for women both on and off the page to openly and freely express themselves.

Born in Denver in 1886, Nell Brinkley had a professional career that spanned almost four decades and included illustration work in some of the most popular publications of the time including the Evening Journal, Harper’s Magazine, and The American Weekly. She was also the creator of original comic strips like The Fortunes of Flossie, Romances of Gloriette, and The Adventures of Prudence Prim that depicted the fantastic one-page adventures of several women protagonists. In a time when women illustrators were few and far between, Brinkley time and time again created works and characters that spoke to and fueled an American public growing into its new century.

It was her most iconic and lasting creation, the “Brinkley Girl,” though, with her bouncy curls, organic disposition, and careless, whimsical air that would inspire generations of young women and comics creators for years to come. Along with becoming a national symbol synonymous with the Roaring ‘20s, the “Brinkley Girl” would also become an icon that would incite nation-wide controversy from New York to Los Angeles.

What made Brinkley such a unique and contentious figure in the early 1900s was her strong sense of ambition, style, and class that imbued her works. At the age of twenty, Brinkley represented a voice that spoke of the possibilities of freedom for women both on the editorial page and in society at large. In a time when the women’s suffrage movement was in full force, Brinkley’s work instilled women with a sense of pride and confidence in themselves. It would be this sense of mystique, confidence, and pose infused throughout all of Brinkley’s works that future comics creators like Dale Messick, the creator of the popular 1940s comic Brenda Starr, and Marie Severin of EC Comics would pick up on and use as inspiration for their own works.

In a time when people critiqued the strange and atypical characters that she was creating—what we would recognize and celebrate as strong female characters today—Brinkley kept on creating, seemingly unfazed by the controversy. Furthermore, even if one person wrote a letter to their local paper asking if there was “any good reason why a woman’s head should be portrayed as weather-beaten moss instead of human hair,” others defended and immortalized Brinkley’s influence by publishing tributes to the creator:

The sweetest, neetest, fleetest maid—the leader in her class,

Give me the stylish, smilish, wilish, dashing Brinkley Lass.

These contemporary plaudits testify to the influence and impact that Brinkley held for women creators and women citizens.

—Contributing Editor Caitlin McCabe

Jackie Ormes

Zelda Jackson Ormes, better known as Jackie, was the first African American woman to make a living as a cartoonist. Between 1937 and 1955, her strips were syndicated extensively nationwide in the black press, featuring black women front and center in roles and social situations they were never accorded in the mainstream media of the day. Ormes got her start in journalism while she was still in high school reporting for the Pittsburgh Courier, which had a nationwide distribution. She relished the excitement of the news business, later telling an interviewer that she “had a great career running around town looking into everything the law would allow, and writing about it.”

Zelda Jackson Ormes, better known as Jackie, was the first African American woman to make a living as a cartoonist. Between 1937 and 1955, her strips were syndicated extensively nationwide in the black press, featuring black women front and center in roles and social situations they were never accorded in the mainstream media of the day. Ormes got her start in journalism while she was still in high school reporting for the Pittsburgh Courier, which had a nationwide distribution. She relished the excitement of the news business, later telling an interviewer that she “had a great career running around town looking into everything the law would allow, and writing about it.”

In 1937 Ormes tried her hand at cartooning with her first strip, Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem. Through the heroine Torchy, a southern transplant to New York who became a performer at the Cotton Club, Ormes was able to address not only racism and prejudice, but also women’s careers and other issues she felt strongly about. She later described herself as “antiwar [and] anti-everything-that’s-smelly.” Although Torchy Brown initially appeared only in the Pittsburgh Courier, before long the strip was syndicated in 14 more black papers across the country.

In 1940 Ormes brought Torchy Brown to an end and briefly moved with her husband to his small hometown of Salem, Ohio, but she was unhappy there and they soon moved again to Chicago. There Ormes got a reporting job with the Chicago Defender, and by the mid-1940s she had conceived of another comic strip, the single-panel Candy. In 1946 she started another single-panel strip, Patty Jo ‘n’ Ginger, which featured the acerbic little girl Patty Jo and her fashion-plate older sister Ginger. Through the voice of Patty Jo, Ormes again commented on issues of the day such as racism, sexism, the military-industrial complex, and McCarthyism. In 1948 she also licensed a Patty Jo doll, which was the first nationally distributed black doll and remains a highly-sought-after collector’s item to this day.

In 1950 a national syndicate persuaded Ormes to bring back Torchy Brown for a new strip, Torchy in Heartbeats. Initially, however, the syndicate only wanted her to provide the art to match a male writer’s storylines. This did not work out well, as Ormes said she constantly had to remind the writer that the character she created “was no moonstruck crybaby, and that she wouldn’t perish between heartbreaks. I have never liked dreamy little women who can’t hold their own.” Eventually Ormes again gained full creative control over the strip, which ran until 1955 when papers like the Courier and the Defender cut their comics sections to give more space to news coverage of the growing Civil Rights movement. Ormes switched to fine art painting until she also had to give that up due to rheumatoid arthritis. She died in 1985, but in recent years she has finally begun to be recognized in the comics industry as a groundbreaking creator.

—Contributing Editor Maren Williams

Tarpé Mills

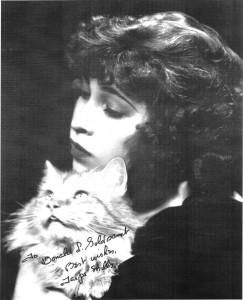

Tarpé Mills, a pseudonym adopted by June Mills in order to conceal her gender to help sell her comics, is the creator of the first major costumed female protagonist in the contemporary comics industry—Miss Fury.

Tarpé Mills, a pseudonym adopted by June Mills in order to conceal her gender to help sell her comics, is the creator of the first major costumed female protagonist in the contemporary comics industry—Miss Fury.

Debuting as a dedicated newspaper comic strip in April 1941 called Black Fury, Miss Fury as she would later be known represented not only a fantastically empowered female character the likes of which the industry had never seen before, but unlike other women characters of the time she was imbued with a complexity and sense of feminine strength that only her creator could capture. Unlike William Moulton Marston’s one-dimensional character Wonder Woman who would appear in comics a few months later, Mills’ Miss Fury was complex both physically and mentally—traits that an ambitious Tarpé Mills herself possessed as a young women seeking work in an industry dominated by men.

Although Mills used her pen name to gain access into the industry, she was quickly be able to hold her own alongside other prominent female creators of the time like Dale Messick (Brenda Starr) and Hilda Terry (Teena). She was included in editorial coverage as a woman creator paving the way for other young women to pursue work in the comics industry. Her comic creations were women characters for women readers; and not just your stereotypical war-time romance and nurse comics that were coming out at the time. Her characters were timely, stylish, have more realistic female figures, and exude an typical confidence and strength.

Although Miss Fury remains Tarpé Mills’ most notable work—a character that has been drawn and redrawn numerous times from the 1940s to today by both men and women—she continued working in the comics industry until her death in 1988. Throughout her career she never sacrificed the strong female protagonist to the sexy, one-dimensional vixens of the time. And though the times initially forced her to adopt a pseudonym to hide her gender from biased readers and publishers, in the end June Mills was able to stand strong as one of the first female creators that paved the way for future women creators to work in the “superhero” genre.

—Contributing Editor Caitlin McCabe

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!