Virtually every public school district across the country has a policy on how challenges to materials should be handled. One of the many benefits of observing these policies is that they help to shield the districts’ own employees — teachers and librarians — from personal attacks hashed out in public. All too often, book challenge debates seem to go off the rails, with a handful of parents making the leap from disagreeing with a book to questioning the professionalism and ethics of the employee who “allowed” it into the classroom or library in the first place.

Virtually every public school district across the country has a policy on how challenges to materials should be handled. One of the many benefits of observing these policies is that they help to shield the districts’ own employees — teachers and librarians — from personal attacks hashed out in public. All too often, book challenge debates seem to go off the rails, with a handful of parents making the leap from disagreeing with a book to questioning the professionalism and ethics of the employee who “allowed” it into the classroom or library in the first place.

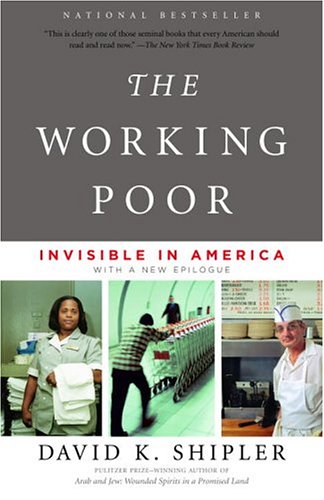

Journalist David K. Shipler, whose nonfiction book The Working Poor: Invisible in America was one of seven books that were informally challenged and temporarily suspended from the curriculum in the Dallas-area Highland Park School District last year, has more than a little first-hand knowledge of the emotional and physical toll that censorship battles take on educators. When The Working Poor was challenged, Shipler happened to be just finishing his latest book Freedom of Speech: Mightier Than the Sword. Suddenly finding himself in the midst of the very issue to which he had devoted months of research and writing, Shipler had the chance to speak to some of the teachers, students, and parents who defended his book.

What he found was that although the superintendent reversed the mass suspension and ultimately none of the seven books were banned, events behind the scenes were not so rosy:

Six of Highland Park’s eighteen English teachers resigned at the end of the year, mostly because of the controversy, which…had brought ‘panic attacks, meltdowns, or outbursts of volcanic anger,’ one told me. Going forward, teachers were required to write long rationales justifying the readings they wished to assign, which were then submitted to panels of community residents. Only the principled, daring, and resolute could resist the temptation of ‘soft censorship’ as a way of avoiding controversial works by not choosing them in the first place. This must happen invisibly all across the country.

Shipler also spoke to Brian Read, an English teacher in Plymouth-Canton, Michigan, who successfully defended Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Graham Swift’s Waterland from a 2012 challenge in his AP English class. As in Highland Park, the superintendent in Plymouth-Canton initially pulled Waterland without following the district’s challenge policy, but later reversed course under public pressure. And although both books were ultimately returned to the classroom, Read still found the pressure too much to bear:

I was happy to fight it and was wonderfully supported by the community, but these things take their toll. This was the beginning of, what was to become, an almost crippling state of anxiety. It was during the book challenge that I began having trouble sleeping and would find myself having panic attacks in the middle of the night.

Read finally decided to stop teaching AP classes altogether since the challenging books used in the college-level curriculum are somewhat more likely to raise parents’ ire. He may have “won,” but future students lost out on a teacher who would have introduced them to complex literature and ideas.

In speaking to Highland Park teachers, Shipler also found that although they are still using The Working Poor in the classroom, they now skip the chapter that was most controversial with a select few parents. That chapter, he explains, contains “women’s inexplicit accounts of having been sexually abused as children,” one of many factors they cite as contributing to the cycle of poverty as adults. Of course, it’s likely that students have all the more interest in that chapter precisely because they skip over it in class: “[D]o kids read the chapter anyway? I have no doubt. They just read that difficult material without adult supervision, which is a loss for them beneath the ostensible victory.”

Ironically, one of the stronger challenge policies we’ve come across is on the books at New Mexico’s Rio Rancho Public School district, where challenges are officially to be treated “objectively, unemotionally, and as a routine matter.” The ironic part is that we only found out about that policy because administrators initially ignored it last year when Palomar by Gilbert Hernandez was pulled from library shelves without review. As in other cases, the district ultimately reversed course and the book was supposedly restored at the beginning of this school year, although students under 18 now need parental permission to check it out. But school districts everywhere would do well to adopt similar language and to realize that challenge policies exist to protect not just educators’ rights, but also their morale and their health.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.