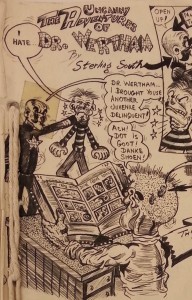

“The Uncanny Adventures of (I Hate) Dr. Wertham”–The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum archives

A discovery in the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum archives proves that fans didn’t necessarily wait for comics to go underground before vocalizing their distaste for the notorious Dr. Fredric Wertham. A 27-page comic book entitled The Uncanny Adventures of (I Hate) Dr. Wertham was uncovered by comics historian Carol Tilley, who wrote about the importance of this lost piece of comics history in a guest post on the library’s website.

Credited to the pseudonym Sterling South, the art is reminiscent of R. Crumb’s infamous underground comix style and the comic contains bits of newspaper bulletins from 1946 through 1948. A tale about how Dr. Wertham duped the U.S. with his pseudoscience, the comic recounts how Wertham came to make his case about the link between comics and juvenile delinquency — a case which would be ultimately documented in his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent and cemented later that year in the Senate subcommittee hearings on comics.

From including figures like pre-Code comics publisher and creator Charles Biro to referencing a radio conversation between critic John Mason Brown and cartoonist Al Capp, in which comics were named the “marijuana of the nursery,” (I Hate) Dr. Wertham is a historical time capsule of events in the late 1940s, enshrined in 27 string-bound, yellowed pages. “Throughout the comic, the unidentified cartoonist deftly incorporates references to key events, locations, and figures,” writes Tilley.

Unlike what really happened with the conclusion of the Senate subcommittee hearings — the formation of the Comics Code Authority and the near-destruction of the mainstream comics market — (I Hate) Dr. Wertham describes a world in which Dr. Wertham is reformed, but ultimately ends up killing himself due to the shame he brought upon an innocent industry. Tilley describes the end of the comic:

Once awake and no longer under the effects of the time travel device, Wertham realizes the error of his anti-comics argument. He endeavors to retract it, but in doing so, he is professionally disgraced and left penniless. The comic ends with Wertham trading in the last of his worldly possessions for a revolver, which he uses to kills himself on a pier.

So who was the real creator behind this small gem in a libraries archive? Tilley makes the big reveal:

Throughout the comic, the unidentified cartoonist deftly incorporates references to key events, locations, and figures beyond those I noted in the summary. Wertham’s groundbreaking Lafargue Clinic in Harlem makes an appearance; in the comic, it’s motto is, “Behind every crook…..there’s a comic book!” The AMCP and its code are namechecked. There’s a shout-out to contemporary provocateur Alfred Kinsey. And then, on page 22 there’s a nameless, crew-cut teenager in a plaid shirt who owns 5,919 comic books, but there’s only one person it could be: David Pace Wigransky.

A credit alongside Sterling South at the end of comic also lists “Dave” Wigransky, a self-proclaimed comics historian who, at the age of 14, rebutted Wertham’s 1948 attack on comics in the Saturday Review of Literature. Even at a young age, Wigransky was an active fan who was dedicated to showing the world that comics weren’t all that bad. Along with critiques of the “research” being circulated in the press, Wigranksy also intended to “write a book on the history of American Comic Magazines during the first half of the twentieth century.”

Wigransky never did get the chance to publish that book before his death in 1969, but his short comic The Uncanny Adventures of (I Hate) Dr. Wertham, drawn at the tender age of 14 or 15, lives on as an intimate piece of comics history reminiscent of the Underground Comix movement, which would arise nearly 20 years after the advent of the censorious C0mics Code Authority. Unfortunately, the impact of the code is still felt even today, as Tilley notes in her closing:

Nearly seventy years have passed since Wertham launched his attack on comics and a young ‘Dave’ Wigransky lambasted our cultural follies. It’s not clear how his comic ended up in the papers of the National Cartoonists Society, but I suspect he sent it to Caniff, who was President of that organization during the late-1940s. I wonder who might have read it, what they thought, and if Wigransky was disappointed not to have his copy—probably the only one—returned. As it stands, my own research published in 2012 suggests that Wigransky was indeed correct to assert Wertham’s disgrace, as the psychiatrist concocted and distorted at least a portion of his findings. I bear no ill toward Wertham the person and don’t believe that his absence would have prevented the Senate hearings or the Comics Code Authority. Still, I also suspect there are some comics fans who might wish for the ending that the teenage Wigransky envisioned for Wertham all those years ago.

You can read the entirety of Tilley’s guest post on the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum blog.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Caitlin McCabe is an independent comics scholar who loves a good pre-code horror comic and the opportunity to spread her knowledge of the industry to those looking for a great story!