Happy Women’s History Month! All through March, we celebrated women who changed free expression in comics. Please enjoy our final weekly compilation of biographical snippets on female creators who have pushed the boundaries of the format and/or seen their work challenged or banned. Like these stories? Please back our Kickstarter to create She Changed Comics as a book! You can pledge here until April 28!

Machiko Hasegawa

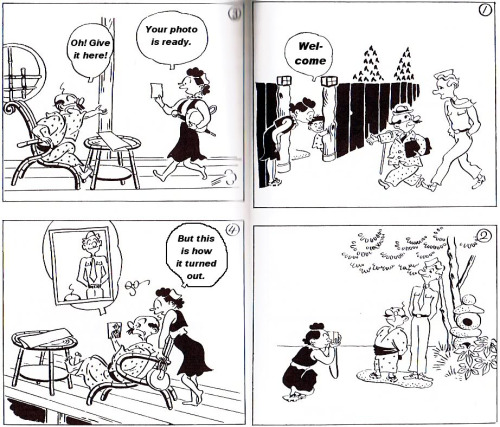

Creator of the popular long-running comic strip Sazae-San, Machiko Hasegawa remains one of Japan’s most beloved manga artists. One of the first female manga artists, Hasegawa has been named the “Godmother of Manga,” had a museum founded in her honor, and inspired many generations of creators—both men and women alike. Her works celebrated a more liberal woman in post-war Japan, and Hasegawa’s cartoons brought a sense of humor and levity to everyday life, making her one of the most successful female cartoonists in the manga industry.

Born in 1920 in Saga Prefecture, Hasegawa got her start in cartoons at the young age of 26, drawing the first Sazae-San strips. Centered around the everyday bustle of housewife and mother Sazae-San, the comic tells the story of ordinary life in post-war Japan. Akin to works like Peanuts or Family Circle, Sazae-San recounts the average and innocent adventures of Sazae-San and her family with a bit of humor and wit. Shortly after publishing the comic herself, Hasegawa’s talent was recognized and she was hired by the prestigious Asahi Shinbun in 1949 to produce an ongoing four panel comic exclusively for the newspaper.

The strip ran until 1974, with an impressive 6,477cartoons seeing print in the series. Hasegawa would depict the stories of a modern day Japanese family, but unlike other cartoons of the day, though, Hasegawa would celebrate and infuse a sense of feminine strength that she felt embodied the modern liberated woman. The sense of empowerment and freedom would be one aspect that would attract readers from all walks of life.

Shortly after its publication in 1955, Sazae-San was adapted into a radio series and then into a weekly animated television show in 1969—a show that is still running today and holds the Guinness World Record as the longest-running animated TV series.

Although Hasegawa’s greatest work would be Sazae-San, the indelible mark that she left on Japanese culture and the manga industry can still be felt today. “Hasegawa’s art is simple and direct in its humor,” writes The Beat. “Certainly it was an influence on such things as Crayon Shinchan — and her name should certainly be added to the list of the most successful female cartoonists of all time.”

–by Caitlin McCabe

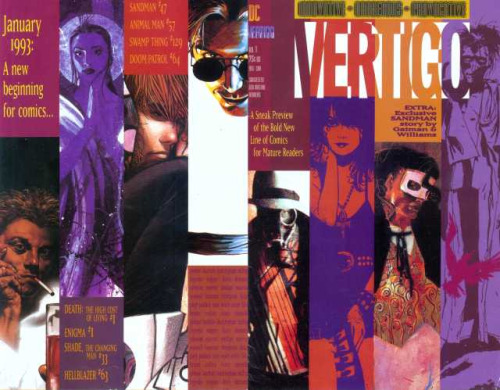

Karen Berger

From modern masterpieces like Y: The Last Man, Fables, and The Invisibles, to seminal classics like V for Vendetta, Preacher, and Sandman, in a time when superheroes glutted the newsstand and comic shops, the former Executive Editor of Vertigo and original power woman of comics, Karen Berger, saw an opportunity to expand the mainstream outside of the superhero realms of Gotham City and Metropolis and helped shape a space for creators to tell their own unique stories.

Dubbed the mother of “the weird stuff” by the New York Times, in her 30 year tenure at DC Berger has left an indelible mark on the mainstream comics industry and has become a point of inspiration for anyone looking to work in comics. “As a young female writer in a very male-dominated industry,” writer G. Willow Wilson said, “Karen was a such a wonderful role model, because she’d done it all.”

In 1979, fresh out of Brooklyn College with a degree in English Literature and Art History, Berger entered the offices of DC Comics looking for a job. An assistant to Paul Levitz, Berger recalls developing an interest not in the meat of DC’s publishing line, the superhero fare, but in some of the off-beat horror and mystery titles DC held onto in the aftermath of the installation of the Comics Code in 1954. “I was fortunate enough to have started at a time, 1979, when DC was still doing other things besides superhero comics,” Berger told Sequential Tart. She continued:

I could just never relate to them. I thought they were too male orientated. I did like the horror, mystery and fantasy comics though. I was lucky I got my start editing those kinds of books. After six months into the job, I was editing House of Mystery. The work I did on that title was in many ways the seeds of how Vertigo really began.

With an eye for the “weird” and “different,” Berger edited DC’s more fantasy and sci-fi oriented series like Wonder Woman, The Legion of Superheroes, Amethyst, and Arion, but her true editorial calling and the space that she would leave her biggest impact was in identifying and cultivating new talent for DC’s newest imprint, Vertigo. “We talked a lot about the creative direction of the titles and the impact that they had in the market,” recalls Berger. “We decided to create a separate imprint for them, a rare thing to do in those days, and to actively expand this sensibility. I came up with a publishing plan for the imprint, the Vertigo name and then we worked on acquiring many new projects.”

Berger’s business savvy, foresight, and belief that solid storytelling could be done outside the boundaries of an established universe spawned what would become the mainstream creator-driven independent realm and quickly pushed her to the top. “Vertigo is successful because of the many talented writers and artists who created so much quality material… That we were consistent and did what we said we were going to do made Vertigo stand out from the other new publishing lines.”

With editing creators’ independent projects, though, came the challenges of managing controversy. Books like Y: The Last Man, Sandman, and Watchmen didn’t just appeal to comics readers looking for something new and fresh, but also attracted the unwanted attention of censors and critics who couldn’t wrap their minds around comics not living up to the stereotype as children’s fare. “Paul and Jenette have given Vertigo a lot of freedom and allowed us to explore and do many controversial things,” notes Berger, and that was one of the imprint’s strongest and most attractive attributes to creators.

For almost three decades, award-winning editor Berger has represented the best of the comics industry and been a staunch supporter of creator-driven storytelling. As Berger states, “I think, with this profession, that my working here for over 20 years is a great example of how women can work and succeed in comics.”

–by Caitlin McCabe

Dorothy Woolfolk

One of the first female editors in the comics industry, Dorothy Woolfolk was an all-around innovator. From the marquee title Superman to DC’s internally neglected and disparaged romance line, Woolfolk was known for carefully fostering fresh talent. In the face of rampant sexism, she helped to ensure the survival of the format by bringing new ideas and creators into the fold.

One of the first female editors in the comics industry, Dorothy Woolfolk was an all-around innovator. From the marquee title Superman to DC’s internally neglected and disparaged romance line, Woolfolk was known for carefully fostering fresh talent. In the face of rampant sexism, she helped to ensure the survival of the format by bringing new ideas and creators into the fold.

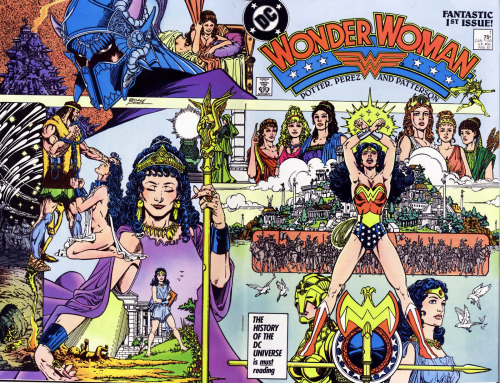

Dorothy Woolfolk (née Roubicek) was born in 1913 in New York City, where she would reside for most of her life. Armed with a high school education, in the 1940s she worked as an editor at various comics publishers, including All-American Publications (one of three that later merged to form DC), Timely Comics (predecessor to Marvel), and EC. During that era, she was an assistant editor on Wonder Woman and also wrote some storylines, making her the first woman to write for the Amazonian heroine and later feminist icon.

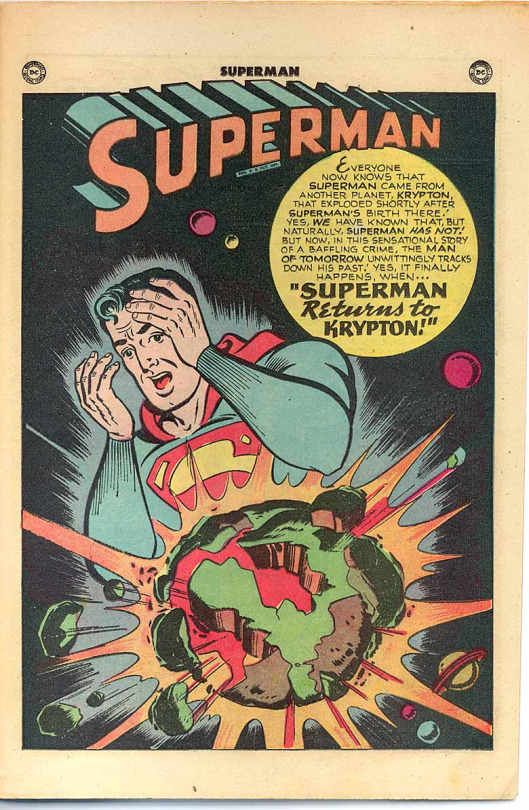

By the late 1940s, Wollfolk was also the first woman to become a full editor at DC. One of her most notable contributions during that time may have been the concept of kryptonite in Superman. The Man of Steel had of course been flying since Action Comics #1 in 1938, but without a single weakness. Woolfolk correctly perceived that a completely invulnerable hero soon became boring, and she pushed for the introduction of some regular plot device that could render him defenseless and thus create narrative tension. Kryptonite had already been introduced in the radio serial The Adventures of Superman in 1943, but it made the leap to comics under Woolfolk’s stewardship with Superman #61 in 1949.

It was also through Superman that she met her third husband William Woolfolk, when she rejected a story he submitted for the series. While raising their two children in the 1950s and ‘60s, she concentrated on writing outside of comics, including some stories in the science fiction magazine Orbit. In 1971 Woolfolk returned to DC as the editor of their entire romance line including Falling in Love, Girls’ Love Stories, Girls’ Romances, Heart Throbs, Secret Hearts, Young Love, and Young Romance. While many of her male colleagues looked down on the titles under her charge, comics historian Tim Hanley says she transformed the line as it “began to explore feminist themes, featuring protagonists with more agency who refused to settle for boys who didn’t treat them properly.”

In 1972 she got the chance to do the same for a DC icon when she took over editing of Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane. Lois had always been a career woman, but under Woolfolk’s tenure, she quit the Daily Planet and became her own boss as a freelance writer. She also broke up with Superman, telling him she was “no longer the girl you come back to between missions,” and moved in with three female roommates who joined in her adventures investigating the crime syndicate called the 100. Of course Superman still made regular appearances, but instead of constantly rescuing a helpless and hapless Lois, he now fought alongside her.

Lois’ radical transformation only lasted for seven issues, however, as Woolfolk was ousted from that title and then from DC altogether. Although then-editor-in-chief Carmine Infantino claimed he fired her because her books were “always late,” Hanley points out that every one of her issues came out on time, and she even “successfully transitioned several titles from six or eight issues a year to monthly series.” Writer and penciller Alan Kupperberg later recalled her as “a real sweetie pie editor” and gratefully credited her with taking chances on fresh young creators such as himself. He also remembered his astonishment when senior male staff accused him of having an affair with Woolfolk, as they were apparently unable to comprehend friendship between men and women. This was part of a pattern of poor treatment towards Woolfolk, Kupperberg said:

The ‘boys club’ always snickered behind her back. ‘Ding-a-ling,’ ‘Wolfgang,’ ‘Dotty Dorothy,’ and worse. Outside of the obvious basic sexism at play at ‘all-male’ DC, I think another reason Dorothy was not very respected comes back to the ‘no running in the halls at DC’ mentality.

Thankfully, that pervasive sexism and staidness has long since been expunged from DC, but there is no doubt that Woolfolk struck one of the first blows. Kupperberg averred that “in the face of the same smugness that allowed Marvel to overtake DC in a romp in those days, Dorothy Woolfolk more than held her own and had fun while she did it.” Although she never returned to work in comics, Hanley reports that she continued to advocate for women in the industry, for instance speaking to a college communications class in 1972 about “the role of feminism in comic books.” In the 1980s she returned to writing rather than editing, with a Scholastic young adult novel series featuring teen detective Donna Rockford. Woolfolk died in Newport News, Virginia, at the age of 87.

–by Maren Williams

Françoise Mouly

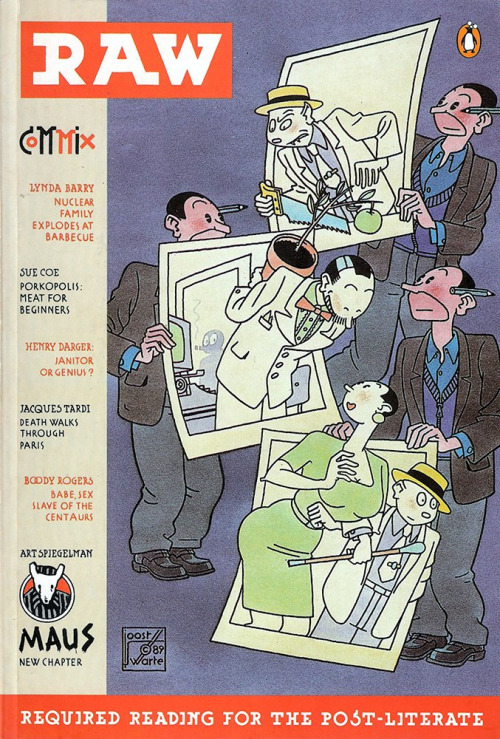

From her underground work, including co-founding RAW magazine, to her current role as comics publisher at Toon Books and as art editor for The New Yorker, Françoise Mouly has become a driving force in the comics industry and mainstream press, especially with regard to her work fighting for the legitimization of comics as art as well as speech protected by the First Amendment.

Born in Paris in 1955, Mouly studied architecture at the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. She moved to the U.S. in 1974 and soon met Art Spiegelman, who would become her husband and frequent creative partner. In those early days, she was surprised at the drastically different prevailing attitude towards comics in this country. Whereas in Europe the comics industry had cultivated a rich and respected history, from the production of high-class satire magazines like Punch to classic comics like Astérix and The Adventures of Tintin, in the United States creators were still struggling to find avenues for their works and were frequently being censored by the still-imposed Comics Code of 1954.

Looking to provide a home for highbrow experimental comics which could elevate the art form in the U.S., Mouly and Spiegelman founded Raw magazine in 1980. Printed on heavy paper stock using high-quality ink, each issue featured custom embellishments such as pasted-in illustration cards and covers artfully ripped by hand. The couple produced 11 issues in as many years, albeit on an irregular schedule, and became a primary stateside conduit for alternative comics. Raw also hosted the serialized version of Spiegelman’s Maus, which later became one of the first American graphic novels widely held in libraries and studied in classrooms when it was published in collected format in 1991.

In 1993 Mouly became art editor at The New Yorker, a position she still holds today. She successfully brought the publication back to its artistic roots while also introducing a wider audience to comics artists such as Sue Coe and Robert Crumb. During her tenure the magazine has frequently featured covers that are iconic and sometimes provocative; perhaps most memorable are the post-9/11 black-on-grey Twin Towers, which she credited to Spiegelman although it was a collaborative effort, and Barry Blitt’s 2008 cover of Barack and Michelle Obama, which satirized the various racial and xenophobic anxieties which bubbled to the surface during that year’s presidential campaign.

Mouly has also brought her meticulous editing skills and comics advocacy to children’s books, first with the RAW Books imprint Little Lit in 2000 and then with the separate press Toon Books in 2008. Prior to establishing Toon Books herself, Mouly recalls in a Smithsonian interview, she had been disappointed in her efforts to interest publishers in the idea of high-quality children’s comics:

I saw that the educational system was prejudiced against comics. I went to see every publishing house and it was a kind of circular argument. It was like, ‘Well, it’s a great idea, but it goes against a number of things that we don’t do.’

Instead, Mouly struck out on her own with Toon Books for beginning readers and met with such critical and popular success that in 2014 she added a middle-grade imprint, Toon Graphics. This is just the latest example of her publishing instincts proving true, she told Smithsonian’s Jeff MacGregor:

All I know is, I know to trust [myself], and that has served me well. If I see something, how something could be, I should go out and do it. I shouldn’t ask permission from anybody. The thing to stay away from, for me, is what unfortunately is too often the case in publishing, that they all want to publish last year’s book. I want to publish next year’s book! The book of the future.

–by Maren Williams and Caitlin McCabe

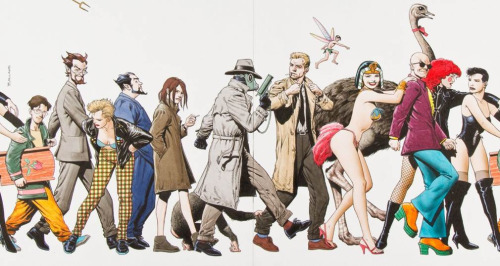

Diana Schutz

Editor, writer, educator, and stanch supporter of creator’s rights, retired Executive Editor of Dark Horse Comics and overall comics veteran Diana Schutz has become a venerable icon in the industry and made immense strides not only in opening the mainstream comics world to independent, creator-owned works, but also opening the doors for women to work in positions of power. From her editorial work on acclaimed series like Sin City, Grendel, and Usagi Yojimbo, to her close relationships with other icons like Will Eisner, Neil Gaiman, and Frank Miller, for over three decades, Schutz has helped shape the modern era of comics and has laid the foundation for its future.

Born in Canada, Schutz got her start in comics at the ground-level in 1978, working at Vancouver-based store The Comicshop. “I started there during the early years of the direct market,” said Schutz in an interview with Comic Book Resources. “And was one of only a few women working behind the counter of the comic book store—one of only a few women shopping at the comic book store!” Despite the fact that the mainstream comics industry of the time focused on male readers and was made up of primarily the superhero books being put out by DC and Marvel, it was at the comic shop that Schutz was introduced to underground comix and the independent works of Dave Sim and Wendy and Richard Pini.

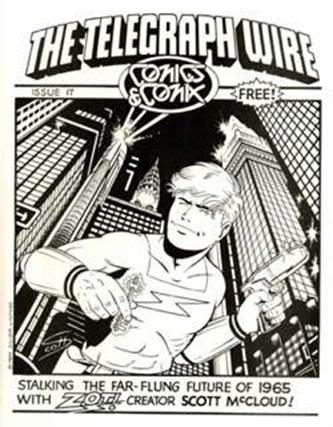

After leaving The Comicshop, Schutz worked on the newsletter/fanzine The Telegraph Wire, had a very short stint as an editor at Marvel, and became Editor-and Chief at Comico. In 1989, Schutz made the move to Dark Horse, where she would make her biggest impact, not only as an editor, but as an advocate for creators’ rights. “When Bob Schreck and I left Comico in 1989, the comics industry was a very different place. If creators wanted to work for Marvel or DC, they had to sign away any claims to copyright, period.”

After leaving The Comicshop, Schutz worked on the newsletter/fanzine The Telegraph Wire, had a very short stint as an editor at Marvel, and became Editor-and Chief at Comico. In 1989, Schutz made the move to Dark Horse, where she would make her biggest impact, not only as an editor, but as an advocate for creators’ rights. “When Bob Schreck and I left Comico in 1989, the comics industry was a very different place. If creators wanted to work for Marvel or DC, they had to sign away any claims to copyright, period.”

This didn’t sit well with Schutz. When then fledgling independent publisher Dark Horse approached her with a job offer, she saw it as an opportunity to create a space for creators to tell their own stories and have their voices heard. “Mike Richardson founded Dark Horse on the principle of creators’ rights,” notes Schutz:

The company paid royalties and offered ownership to writers and artists; these were all political ideals that were really important in the industry and weren’t taken for granted back then as they are now. Many of us felt very strongly that creators had not been getting treated properly by the corporate superhero publishers. So it was politically important to us to go with Dark Horse because of the company’s stance towards creators and the opportunities it offered creators.

For over two decades at Dark Horse Schutz would edit some of the publisher’s biggest projects and quickly rose to the position of Executive Editor. Her attention to detail, compassion for the storytelling, and approach to preserving the creator’s intent behind their work made her one of the most in-demand editors at the company.

When she retired from her position at Dark Horse in 2015, though, Schutz didn’t stop working in the industry. Obtaining a Master of Arts in Communications at the University of Portland, Schutz now teaches students about comics at Portland Community College, where she continues to share her experience and expertise with a whole new generation of comics fans. Looking back on her career in comics, how the industry has evolved, and where it’s going, Schutz offers the following insight:

As the comics industry continues to become more girl-friendly, I see more and more women now entering the field, and one result of women making publishing decisions is that there are more reading choices for women than ever before, which continues to bring more women in, and so the one feeds the other. Things have definitely changed since 1978 and my first day on the job at The Comicshop, when a customer asked the owners, “Who’s the skirt?”

–by Caitlin McCabe

Jenette Kahn

For 26 years, DC Comics was run by a woman who oversaw one of the company’s most successful periods, not just in terms of revenue, but also in the expansion of what comics were capable of and how they were perceived outside of the industry.

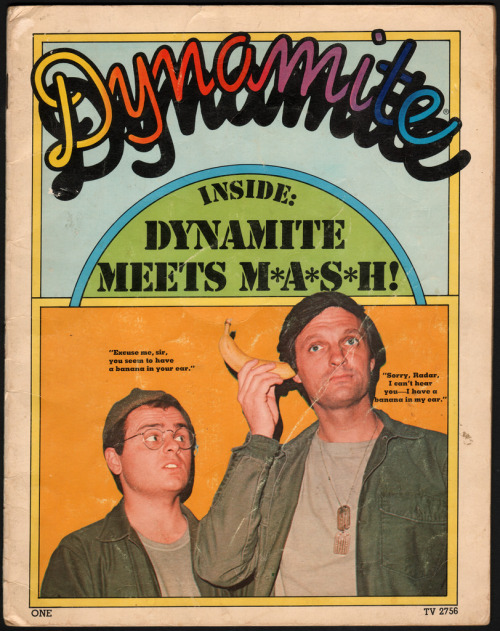

Jenette Kahn got her start in children’s publishing. Her first children’s magazine, Kids, was drawn for and by younger readers. It tackled topics still relevant today – drug abuse, diversity, animal protection, and the environment – and ran from 1970 to 1975. Kahn then established Dynamite for Scholastic, Inc. The magazine became the most popular publication in the corporation’s history and is credited with improving the fortunes of the company. Kahn worked on only a few issues of Dynamite before moving on to Smash, a children’s pop-culture magazine, for Xerox Education.

In 1975, Kahn was approached by Warner Communication’s Bill Sarnoff, who asked her to be Publisher for his failing comic book company, National Periodical Publications. In a video for MAKERS, a women’s platform that collects first-hand accounts from women in leadership, Kahn talked about her experience entering the male-dominated comics industry as the first female Publisher:

The beginning was difficult. We basically manufactured male fantasy, and everyone who created those fantasies, they were men, too. There was a lot of fear and loathing that I had been hired. It was said that one of my all-time favorite editors was throwing up in the men’s room when he heard about it.

One of the first things Kahn did was push for renaming the company. It had been known colloquially as DC Comics for years, but the name didn’t become official until 1977, a year after Kahn began her tenure as Publisher. In 1981, Kahn was promoted to President and Editor-in-Chief of DC Comics.

Beyond rebranding the company, Kahn realized that any revitalization of comics had to involve creators’ rights:

I felt that there were artists and writers who had great ideas, and they were not bringing them to us. So, I went in to Bill Sarnoff, and I said, I believe we could be publishing many new titles, many great ideas, and what’s standing the way is that we don’t share revenue. And that argument actually carried the day.

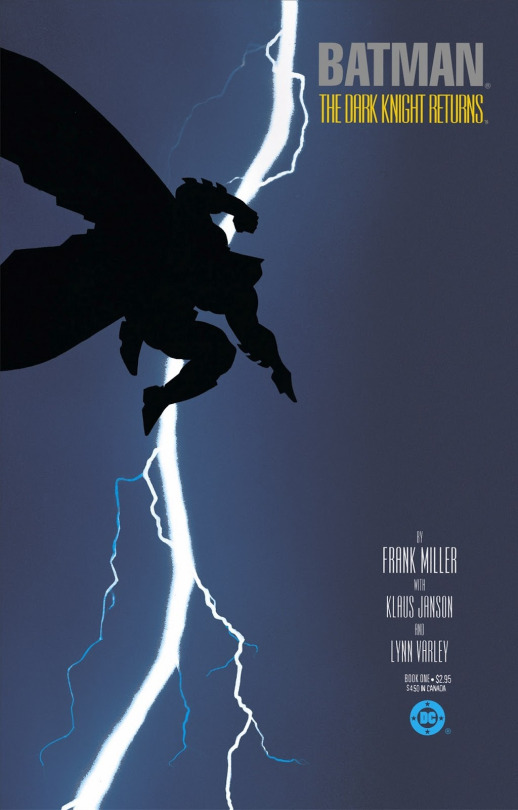

In addition to advocating for creators’ rights, she also changed the focus of books from plot-driven stories to character-driven stories. “This was a much more modern approach and also a more adult one,” she told Sequential Tart’s Jennifer Contino in a 2001 interview. In the process, she was able to enlist Frank Miller, who at the time was finding large audiences writing and drawing for Marvel. The result included a book that helped change the face of comics: The Dark Knight Returns.

Kahn described the impact of Dark Knight and the comics that soon followed to Contino:

Dark Knight signaled a seismic shift. All the extraordinary books that have come after it, Watchmen, The Killing Joke, Arkham Asylum, The Sandman, Preacher, Planetary, The Authority, 100 Bullets (and great books from other publishers, too, like American Flagg) owe a debt to it. Dark Knight turned comics on its head. And it ushered in a new era of formats. With paper of the highest quality and perfect binding, Dark Knight was more book than comic. Unlike magazines and other supposedly disposable ephemera, Dark Knight and the comics it made possible could take their place on the library shelf.

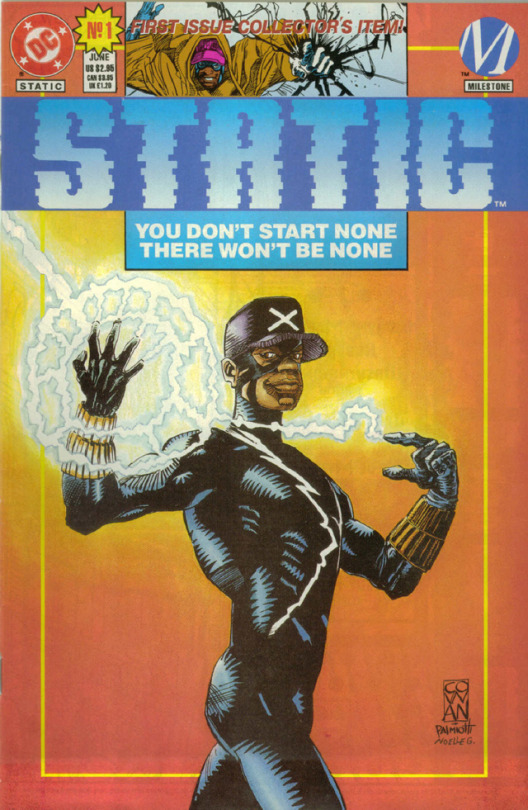

Under Kahn’s leadership, DC Comics also saw the launch of the Vertigo imprint, and with it, Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman and other titles that garnered the interest of audiences outside the mainstream superhero lines. Kahn also oversaw the addition of the short-lived but immensely influential Milestone imprint, which introduced the comics world to something it had long been lacking: creators and characters of color.

Kahn’s emphasis on diversity also found a home in the fabric of DC Comics itself. When Kahn joined DC, she was one of 3 women in a staff of 35. By the time she left DC in 2002, the staff had increased to 250, and half were women.

Kahn wasn’t just the first woman to lead a major comics publisher – she helped change the face of the medium. Under Kahn’s 26 years of leadership, DC Comics shrugged off the self-censorship of the Comics Code, strengthened creator rights, and attracted a wider audience that included more women and people of color. Many of the titles that Kahn published proved that comics could be used to tell sophisticated stories that appealed to adult audiences and fostered unprecedented acceptance of comics as literature.

–by Betsy Gomez

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!