The vast majority of modern book challenges and bans in the United States, across all types of libraries, happen because a parent or other adult feels that some topic covered is “too adult” for not only their own children, but all children. The pitfalls of this mentality which ignores the individual needs and varying developmental rates of minors are illustrated in a recent School Library Journal column by Pat Scales, former chair of the American Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Committee.

The vast majority of modern book challenges and bans in the United States, across all types of libraries, happen because a parent or other adult feels that some topic covered is “too adult” for not only their own children, but all children. The pitfalls of this mentality which ignores the individual needs and varying developmental rates of minors are illustrated in a recent School Library Journal column by Pat Scales, former chair of the American Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Committee.

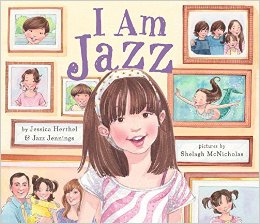

In the most recent edition of her regular Q&A column on censorship issues, Scales addressed two questions that touch on this reductive mindset from different angles. In the first, a middle school librarian recounts hearing from a parent volunteer that some bookstores choose to shelve picture books about gender-nonconforming children–namely I Am Jazz and Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress–in the teen section. As private businesses, bookstores can impose whatever restrictions or unique shelving schemes they like, but Scales points out that this practice does a disservice both to the books’ intended audience which is unlikely to find them, and to the publishers and creators who are prevented from connecting with their potential market.

In public schools and libraries, restricted shelving presents the added wrinkle of impeding users’ First Amendment rights. That certainly hasn’t stopped attacks on these particular books in government-run institutions, however. I Am Jazz, the age-appropriate picture book memoir of transgender teen Jazz Jennings which was co-authored by Jessica Herthel and illustrated by Shelagh McNicholas, has been a particularly frequent target of attacks by parents who object to any mention of gender-nonconformity in children’s literature.

Most recently, in December 2015 Wisconsin’s Mount Horeb Area School District cancelled a planned district-wide reading of I Am Jazz under threat of a lawsuit from Liberty Counsel, which claimed that the reading would “miseducate children with what essentially amount to propaganda and mistruths.” Although the community came together in fine fashion and organized two extracurricular public readings of the book–one coordinated by a district parent and one by Mount Horeb High School’s Straight and Gay Alliance–the fact remains that a baseless threat was enough to intimidate a public institution out of sharing basic knowledge with students. The incident is all the more troubling because the reading was originally planned to support one student who was making her own gender transition at the time.

The other book mentioned in Scales’ first question, Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress written by Christine Baldacchino and illustrated by Isabelle Malenfant, fared better when it was challenged last year in Michigan’s Forest Hills Public School District. After a teacher read the book to one third-grade class because students had been asking questions about “people [who] dress in ways that were unfamiliar to them,” a student’s father claimed that it was “promoting another life” and might give his son ideas that he would not have had otherwise. In that case, Superintendent Dan Behm firmly stood by Morris Micklewhite as a carefully chosen reading selection that addressed a particular pedagogical need: answering questions that had been preoccupying the students to such an extent that they were distracted from their core studies.

Two other picture books about gender-nonconforming boys, My Princess Boy and Jacob’s New Dress, have also been targeted by parents and even lawmakers who find the subject matter inappropriate for children. Like Morris Micklewhite, neither book makes any definitive statement on the main character’s gender or sexual orientation; they simply show young readers that there are some boys who like to wear dresses. Moreover, My Princess Boy is inspired by author Cheryl Kilodavis’ own son Dyson, who was five when the book was published in 2011 and today is a well-adjusted pre-adolescent who still prefers traditionally feminine clothing. As Scales points out in her column, for every parent who doesn’t want their child to read age-appropriate about gender-nonconforming people, there are likely many more who do want their children to learn about the topic so they can feel secure with their own gender identities and treat all of their friends and classmates with the same respect.

Scales’ second question also came from a middle school librarian, who recalled the adolescent experience of surreptitiously passing around “forbidden” books like Judy Blume’s Forever, Norma Fox Mazer’s Up in Seth’s Room, and J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Somewhat worryingly, the librarian who should already be versed in the principles of intellectual freedom asked Scales “how prevalent this behavior is” and whether it is cause for concern.

Of course, Scales responds that on the contrary this is “all part of being an adolescent,” and the fact that something is forbidden naturally makes it all the more appealing for youngsters. Among the most recent manifestations of this phenomenon is the cycle of panicked adult suppression and eager teen consumption of the Netflix series Thirteen Reasons Why and the book by Jay Asher upon which it was based. Although parents’ and school administrators’ terror over the topic of teen suicide is understandable, some schools have gone so far as to forbid students from bringing even their own personal copies of the book onto campus. Although many adults seem to forget their own adolescent behavior, most of us could conclude that this blanket ban likely does nothing to actually keep the book out of students’ backpacks and lockers, but simply ensures that adults won’t see it or be available to talk about it.

In both of these cases, Scales’ response amounts to respecting juveniles enough to understand that they are individuals with different needs and curiosities at different stages of their lives. If all adults could approach curricula and library collections with that fact in mind, we would undoubtedly see a great reduction in censorship attempts!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.