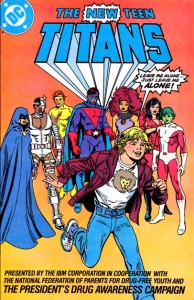

Throughout history, state and federal governments have utilized popular culture to spread their message. Given the effectiveness and popularity of sequential art, it should be no surprise that comics would be enlisted into the cause. And much like Marvel’s merry mutants, comics protected a world that feared and hated them. This was apparent in 1954, when the same government that made comics also held hearings that nearly destroyed the medium forever.

Throughout history, state and federal governments have utilized popular culture to spread their message. Given the effectiveness and popularity of sequential art, it should be no surprise that comics would be enlisted into the cause. And much like Marvel’s merry mutants, comics protected a world that feared and hated them. This was apparent in 1954, when the same government that made comics also held hearings that nearly destroyed the medium forever.

Soren Kierkegaard wrote, “Irony is a disciplinarian feared only by those who do not know it, but cherished by those who do.” Consider: the fact that Oedipus is the murderer he is looking for; that the Scarecrow realizes that he is extremely intelligent only after his quest for a brain, the Tin Woodsman realizes he already has a heart, and the Lion realizes that he is bold and courageous; and the fact that Mary Poppins sings about staying awake to lull her charges to sleep. Or as this week’s article explores, the irony that at the same time the government was condemning comics and creators, the same government was also using public funds to hire the creators it was attacking to produce comics that promoted government sanctioned messages. This week, it’s all about the history of government comics.

Governments recognize the importance of motivating their citizens through mass media and popular culture. The United States is no exception. Even the Founding Fathers recognized the important role played by visual media on society as early as 1770. Take for example, an event that occurred on March 5, 1770, when a detachment of British troops fired on a mob in self defense after they were attacked. Despite the fact that the troops were acquitted in a trial (in which they were represented by patriot and later President John Adams), this altercation was memorialized in an engraving as the “Boston Massacre” by Paul Revere (who himself would become a pop-culture icon of the time). This anti-British propaganda inflamed American sentiments and motivated previously loyal colonists to oppose the British rule and support American independence.

Governments recognize the importance of motivating their citizens through mass media and popular culture. The United States is no exception. Even the Founding Fathers recognized the important role played by visual media on society as early as 1770. Take for example, an event that occurred on March 5, 1770, when a detachment of British troops fired on a mob in self defense after they were attacked. Despite the fact that the troops were acquitted in a trial (in which they were represented by patriot and later President John Adams), this altercation was memorialized in an engraving as the “Boston Massacre” by Paul Revere (who himself would become a pop-culture icon of the time). This anti-British propaganda inflamed American sentiments and motivated previously loyal colonists to oppose the British rule and support American independence.

Given the effect that comics had on the American psyche, it was only a matter of time until the medium would be enlisted to support the role of government. Of course, like most propaganda mediums, comics were first utilized to garner support for war in World War I. The United States carefully selected images that would inspire the troops abroad, generate loyal support stateside, and instill fear in the enemy. To this end, President Woodrow Wilson created, through Executive Order 2594, an independent agency called the Committee on Public Information (CPI), which consisted of George Creel (chairman) and as ex officio members, the Secretaries of: State (Robert Lansing), War (Newton D. Baker), and the Navy (Josephus Daniels). The role of CPI was to influence U.S. public opinion regarding American participation in World War I. Of course, CPI had its critics and came under fire for embellishing stories (The New York Times referred to the organization as the “Committee on Public Misinformation” after it accused the CPI of deceiving “the American people by the statement describing the attack upon our transport ships by German submarines, issued by Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels on the evening of July 3.”). The CPI, and especially it chairperson, were also accused of inappropriate censorship. This came to a head when the CPI attempted to silence newspapers like The Call and The Jewish Daily Foreward. In his book, Walter Lippmann and the American Century, Ronald Steel writes

Given the effect that comics had on the American psyche, it was only a matter of time until the medium would be enlisted to support the role of government. Of course, like most propaganda mediums, comics were first utilized to garner support for war in World War I. The United States carefully selected images that would inspire the troops abroad, generate loyal support stateside, and instill fear in the enemy. To this end, President Woodrow Wilson created, through Executive Order 2594, an independent agency called the Committee on Public Information (CPI), which consisted of George Creel (chairman) and as ex officio members, the Secretaries of: State (Robert Lansing), War (Newton D. Baker), and the Navy (Josephus Daniels). The role of CPI was to influence U.S. public opinion regarding American participation in World War I. Of course, CPI had its critics and came under fire for embellishing stories (The New York Times referred to the organization as the “Committee on Public Misinformation” after it accused the CPI of deceiving “the American people by the statement describing the attack upon our transport ships by German submarines, issued by Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels on the evening of July 3.”). The CPI, and especially it chairperson, were also accused of inappropriate censorship. This came to a head when the CPI attempted to silence newspapers like The Call and The Jewish Daily Foreward. In his book, Walter Lippmann and the American Century, Ronald Steel writes

By October 1917 the situation had grown so serious that Lippmann [an adviser to Wilson who was also a journalist, and co-founder of the New Republic] decided to take it up with Colonel House [a close adviser to the President]. Although the colonel was not particularly sensitive to the civil liberties issue, he agreed with Lippmann that attempts to muzzle the press were undermining national morale and rebounding against the President. He asked Lippmann to draw up a memorandum for Wilson. Radicals and liberals were in a “sullen mood “over censorship of the socialist press, Lippmann noted in his memo. The best course for the administration was to be “contemptuously disinterested” in socialist diatribes against the war, while respecting the right to free speech. Censorship should “never be entrusted to anyone who is not himself tolerant, nor to anyone who is unacquainted with the long record of folly which is the history of suppression.” While he refrained from underlining the obvious, Lippmann clearly had Creel in mind as one to whom such delicate tasks should not be entrusted.

Of Course, Creel did not agree. He wrote in his memoir, How We Advertised America:

In no degree was the Committee an agency of censorship, a machinery of concealment or repression. Its emphasis throughout was on the open and the positive. At no point did it seek or exercise authorities under those war laws that limited the freedom of speech and press. In all things, from first to last, without halt or change, it was a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s greatest adventures in advertising… We did not call it propaganda, for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, for we had such confidence in our case as to feel that no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of the facts.

Given the explanation of irony, I should note that Creel’s quote about not being agent of censorship aside, one of the the agencies that replaced the CPI in World War II was called “The Office of Censorship.”

Of, course, what is more important for this article is the fact that the CPI laid the groundwork for what would be known as government comics. In its mission, the CPI utilized used every medium available to create enthusiasm for the war effort and enlist public support against foreign attempts to undercut America’s war aims. In 1918, the CPI formed “The Bureau of Cartoons.” the role of the Bureau was to suggest pro-government slogans and themes to newspapers and editorial cartoonists to help advance the government’s message. The bureau then collected these cartoons into a book, which was sold by the Treasury to support an initiative called The Third Liberty Loan Campaign. (On the subject of irony, I should point out that while the campaign, which relied on celebrities and the Boy Scouts to appeal to emotions and highlight the profitability of the bonds, was a huge funding success for the war, the public soon discovered that the value of the bonds had dropped 80 percent of their face value after the war.) And while The Cartoon Book was printed long after the 1842’s The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck or the 1897 collection of The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Flats, the CPI’s comic predates Famous Funnies, the first credited comic book in America, by fifteen years.

Of, course, what is more important for this article is the fact that the CPI laid the groundwork for what would be known as government comics. In its mission, the CPI utilized used every medium available to create enthusiasm for the war effort and enlist public support against foreign attempts to undercut America’s war aims. In 1918, the CPI formed “The Bureau of Cartoons.” the role of the Bureau was to suggest pro-government slogans and themes to newspapers and editorial cartoonists to help advance the government’s message. The bureau then collected these cartoons into a book, which was sold by the Treasury to support an initiative called The Third Liberty Loan Campaign. (On the subject of irony, I should point out that while the campaign, which relied on celebrities and the Boy Scouts to appeal to emotions and highlight the profitability of the bonds, was a huge funding success for the war, the public soon discovered that the value of the bonds had dropped 80 percent of their face value after the war.) And while The Cartoon Book was printed long after the 1842’s The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck or the 1897 collection of The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Flats, the CPI’s comic predates Famous Funnies, the first credited comic book in America, by fifteen years.

At the end of the war, The CPI stopped its work and was disestablished by Congress on June 30, 1919. On August 21, 1919, President Wilson signed Executive Order 3154, which officially terminated the CPI’s activities. The United States’ early experiment with the use of government comics had ended.

Meanwhile, comics were becoming more and more popular among U.S. consumers. Beginning with the publication of Famous Funnies in July 1934 and continuing with the first appearance of Superheroes in June 1938, comics provided the American people both with the humorous escapism necessary to survive the Great Depression, as well as some of the motivation to get out of the Depression through the embodiment of American spirit. President Roosevelt was certainly aware of the power of pop culture. In 1936, he said “When the spirit of the people is lower than at any other time during this Depression, it is a splendid thing that for just fifteen cents an American can go to a movie and forget his troubles.” The same was true for a 10-cent comic. As Larry Tye explains,

Superman was a money machine from the get-go, but he was also a butt-kicking New Dealer. . . . His message was simple and direct: Power corrupts. The average Joe deserves a super-powered friend and rich SOBs deserve a boot in the rear. . . . These were the very lessons that Depression-era America wanted to hear and that FDR preached in his fireside chats and legislative crusades.

So, given the success of comics, it should be no surprise that in 1942 the Advertising Research Foundation released a study that determined that the comics section of the newspaper was the most read section of the paper by adults (excluding the advertisements). A later study, performed by the Market Research Company of America found that roughly half of the U.S. population (about 70 million Americans), read comic books. And while the ages of readers heavily favored children, with 95 percent of all boys and 91 percent of all girls between the ages of six and eleven reading comic books, the study also showed that 41 percent of men and 28 percent of women aged eighteen to thirty admitted they regularly read comics. In fact, Dr. Arnold T. Blumberg, in his book Pop Culture with Character, puts the date much earlier. He writes :

As early as the April 1933 issue of Fortune Magazine, the business world recognized the power of comics to communicate as well as entertain, noting that over $1 million dollars was spent in 1932 for advertising space in newspapers adjacent to the funny pages. In the years to come, promotional comics of all types would become a mainstay of the industry, pairing superheroes, funny animals and other characters with social, political, and cultural topics from banking to drug addiction.

These were numbers the United States government could not ignore, especially in light of the United States eventual involvement in World War II later that year. In response, the Bureau of Intelligence (the predecessor to today’s FBI and successor to much of the CPI) created a series of intelligence reports analyzing the content of comics at the time for use by the Office of War Information (the OWI).

The OWI did not like what they saw in these intelligence reports. First, two thirds of the comics surveyed had nothing to do with the war effort and the ones that did were not concerned with fighting or winning the war and the themes of the books were inconsistent with the goals of the OWI. As Richard L. Graham states in his book, Government Issue, Comics for the People, 1940s-2000s:

Perhaps it was the comics’ portrayal of the enemy during this time that was most troubling to the OWI. The Bureau of Intelligence observed that mainstream comic strips at the time had no trouble using exaggerated physical stereotypes, depicting Nazis as Teutonic buffoons and the Japanese as blood-drooling torturers. While these characterizations of the enemy as “the other” provided an impetus for hatred and stirred strong emotional reactions at home and abroad, they were often accompanied by portrayals o( the enemy as lazy and posing little threat. The OWl felt these depictions were too simplistic and misleading and could lead to overconfidence (although this didn’t necessarily stop the OWl from using similar depictions in its own materials).

As a result, the OWI created their own media division to distribute comics that would promote its own messages about civilian sacrifice and the importance of the war effort. This division also assisted other agencies to get their messages out. These organizations included: the Department of the Treasury, the Federal Security Agency, and the branches of the United States Military.

Government comics were re-born.

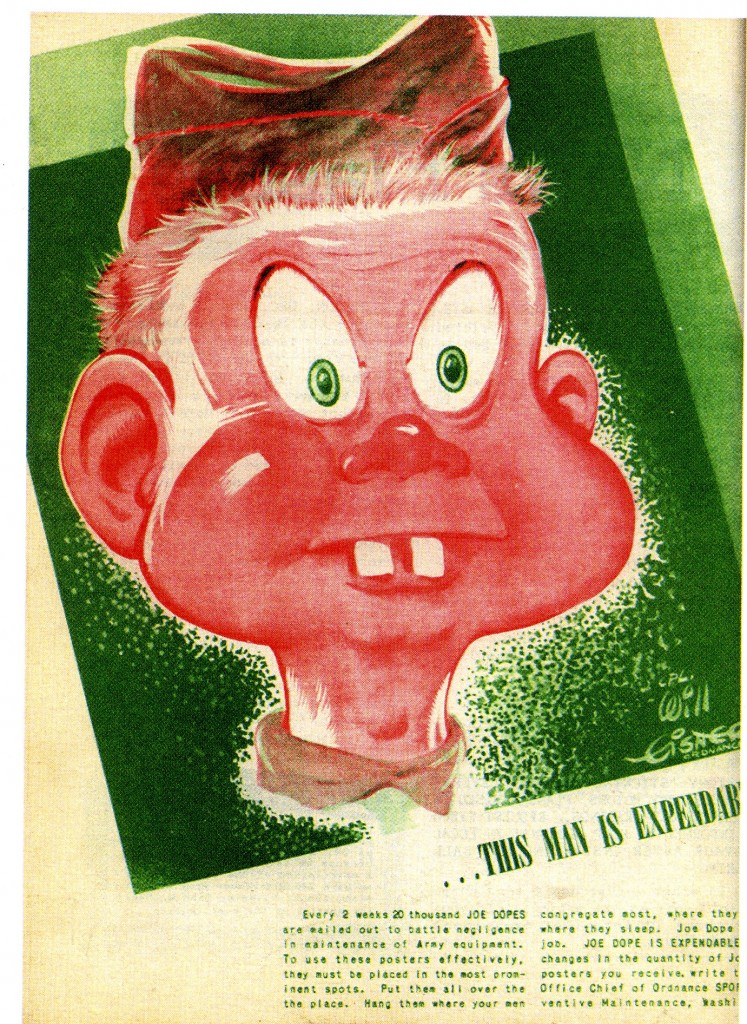

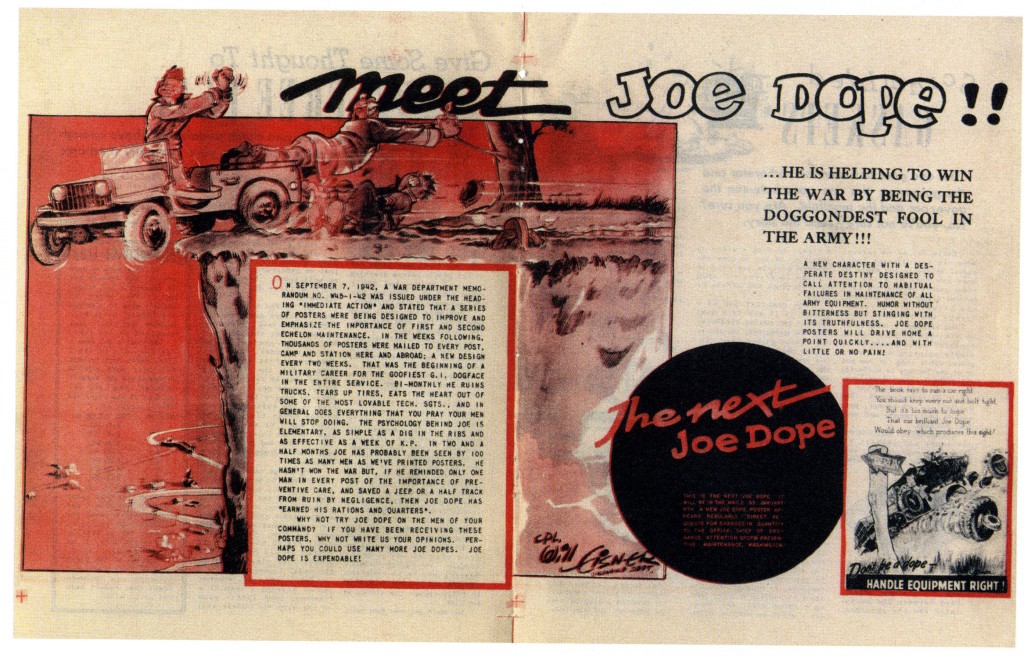

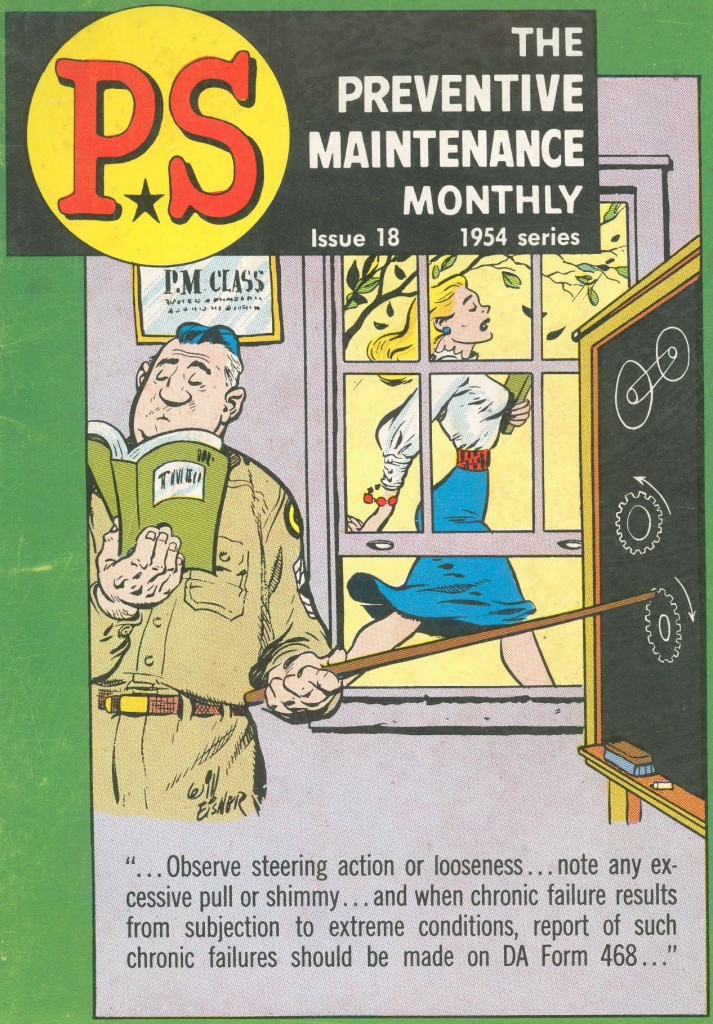

These early government comics attracted and utilized high quality artists and writers in their production. For example, and as can be seen below, comic legend Will Eisner created a series of stories for the US Army.

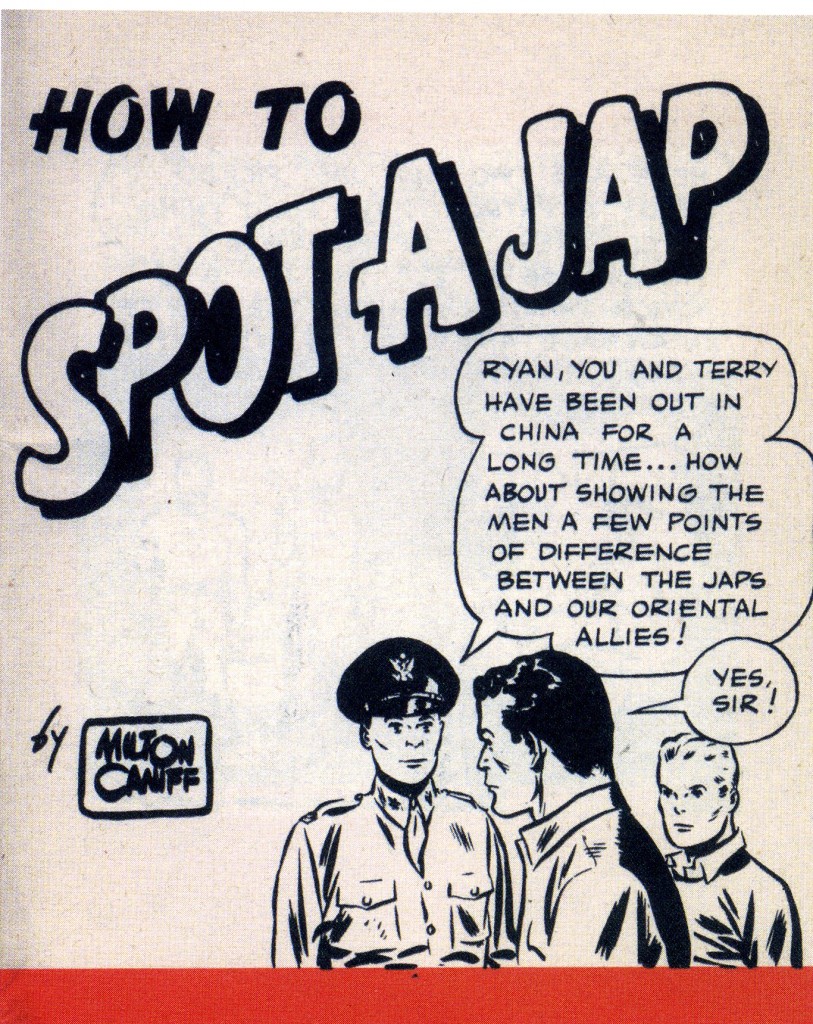

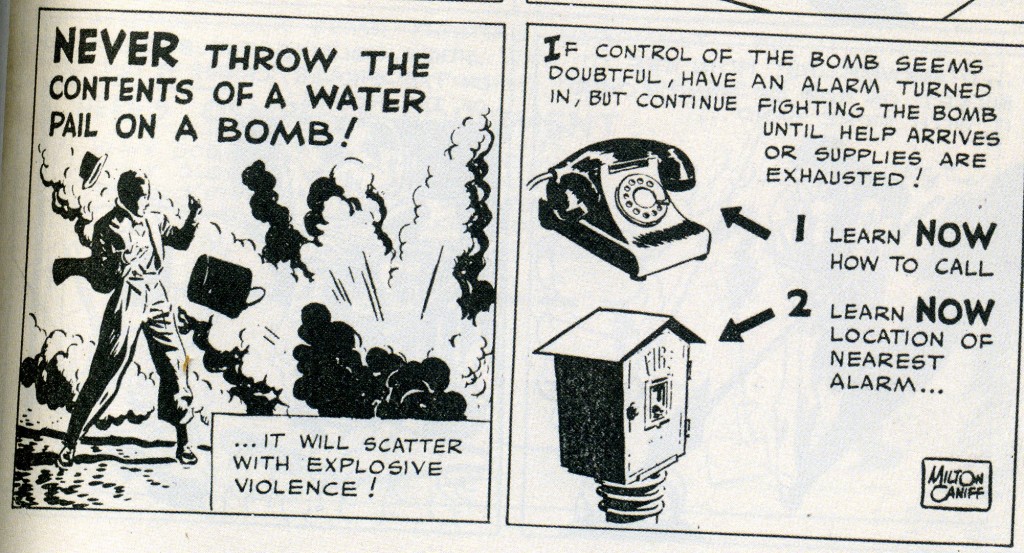

Milton Caniff, the creator of Terry and the Pirates, lent his skills to government training manuals, pocket guides, and bond selling.

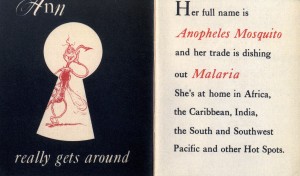

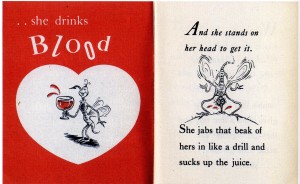

Theodor Suess Geisel (whom we know as Dr. Suess) wrote about malaria and for other instructional manuels (he also worked on cartoons with Frank Capra).

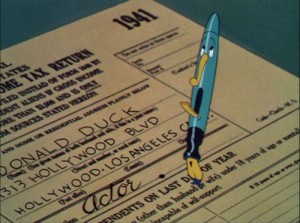

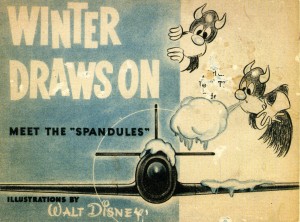

Walt Disney even got into the act by creating cartoons, comics, and training pamphlets. Although unrelated to comics, I found that the highlight of Walt Disney’s war work was the animated short “A New Spirit” that stars Donald Duck and stresses the importance of paying taxes (we also get to see a copy of his tax return).

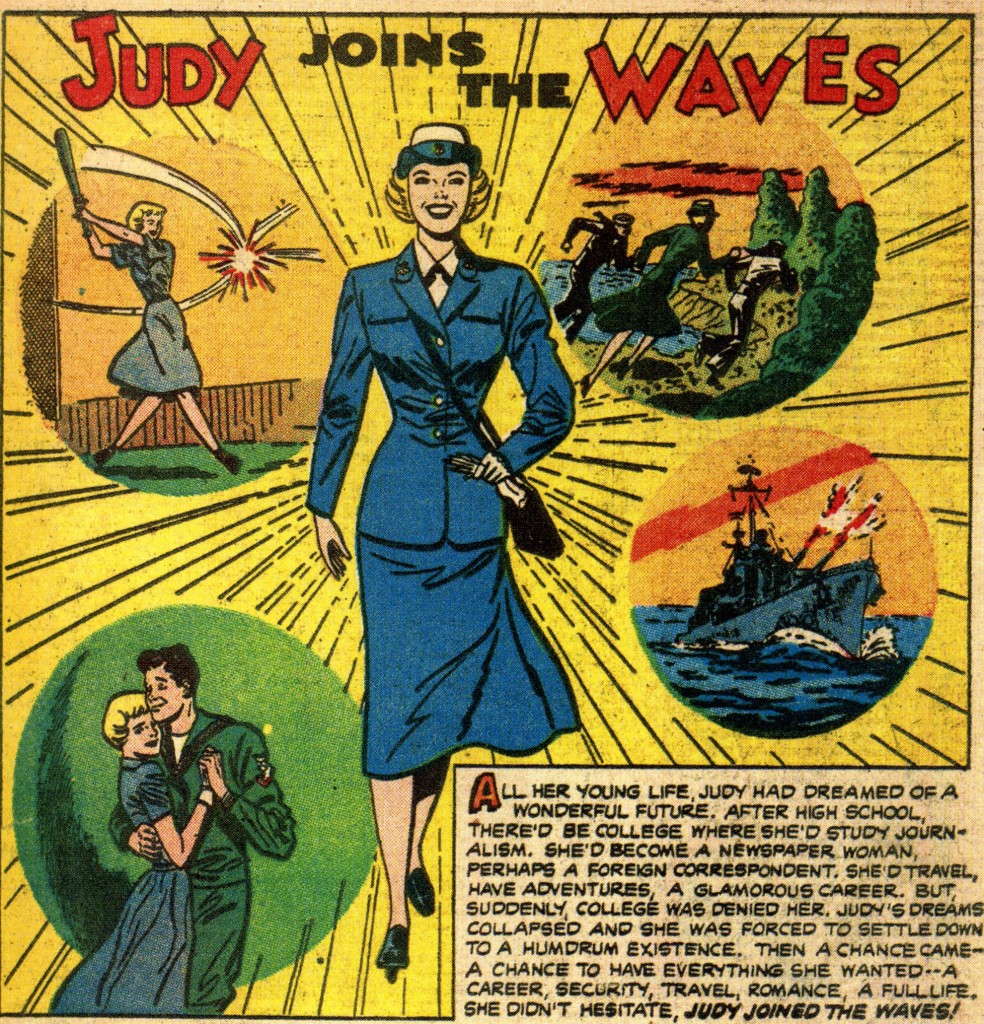

Even after the war ended, the government still produced comics in support of the military effort. These were placed in recruitment offices and given away to students. For example, this is a scene from Judy Joins the WAVES, which promotes the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES):

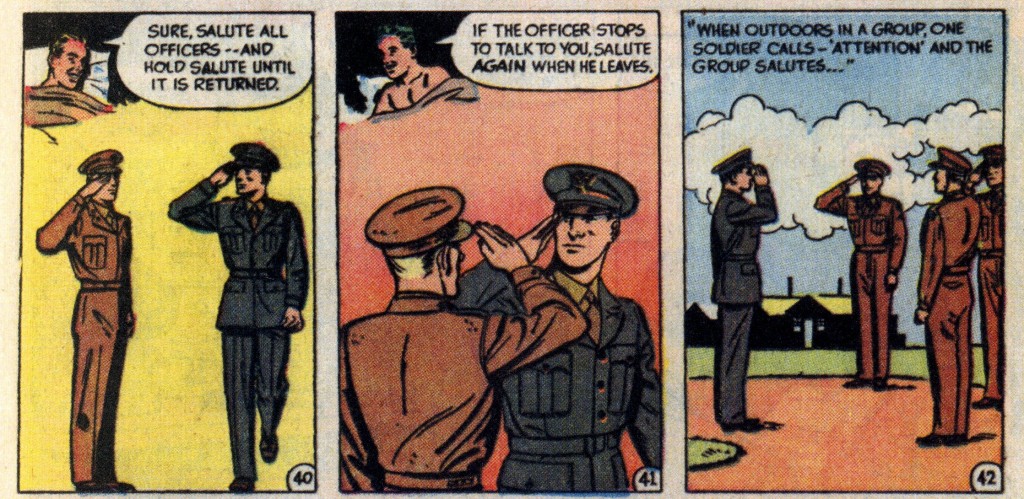

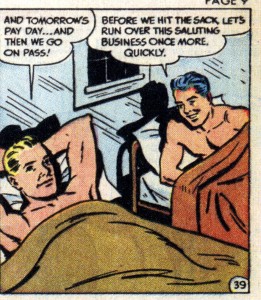

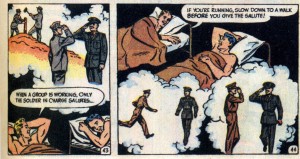

Al Avison, co-creator of the Whizzer and noted Captain America artist, wrote Military Courtesy, a guide to saluting.

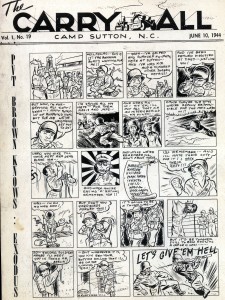

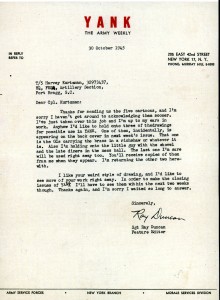

Harvey Kurtzman, later of EC Comics, Mad Magazine, and Playboy fame, drew comics for Yank, the Army weekly.

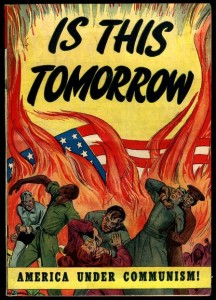

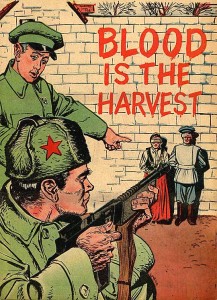

Even the Catholic Church got in on the act when Father Louis Gales founded the Catechetical Guild Educational Society in 1942 as a means of publishing Catholic comic books. The Guild’s first series, Topix, gave Peanuts’ creator George Schulz his first professional work in comics (he lettered the book). The Guild also published two anti-communism books in the late 40s called Is This Tomorrow and Blood is the Harvest. The books certainly fanned the flames of communist conspiracy theory in America.

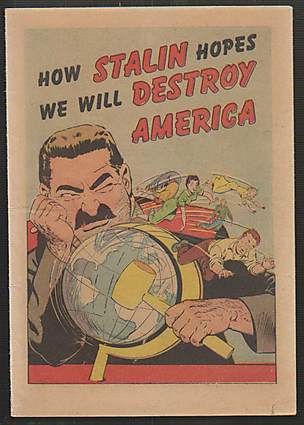

And speaking of anti-Communist Propaganda. This little piece of subtlety came out in 1951 as a free newspaper giveaway:

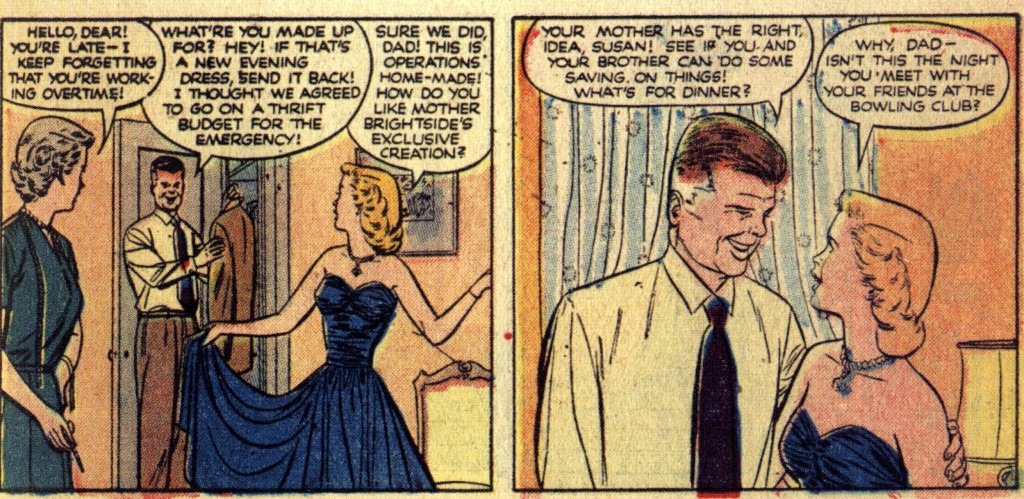

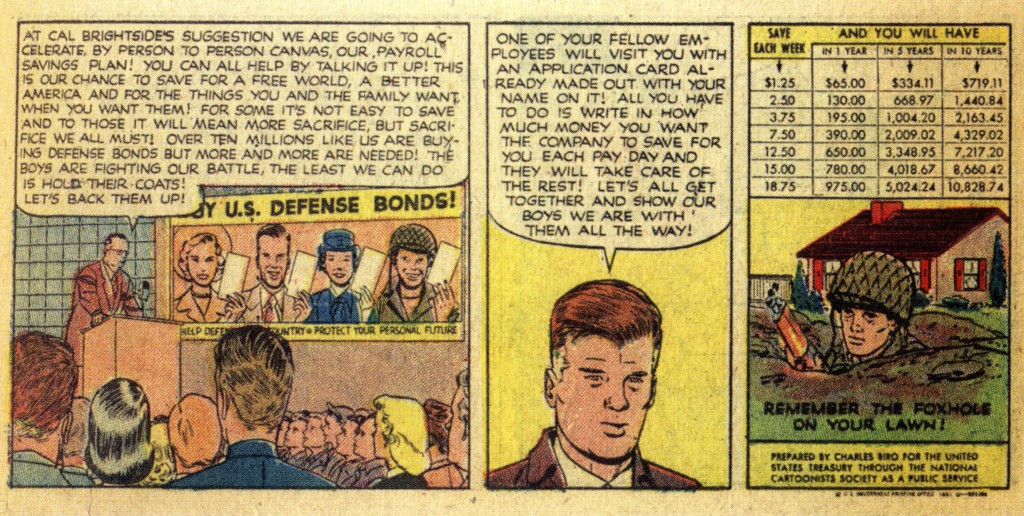

Of course, the use of government comics was not limited to military propaganda. If there was a topic that was important to the government, there would be a comic made. There were books on how to save money. For example, Charles Biro, creator of Airboy, wrote and drew Foxhole on your Front Lawn for the United States Department of the Treasury about Savings bonds and other ways to save money.

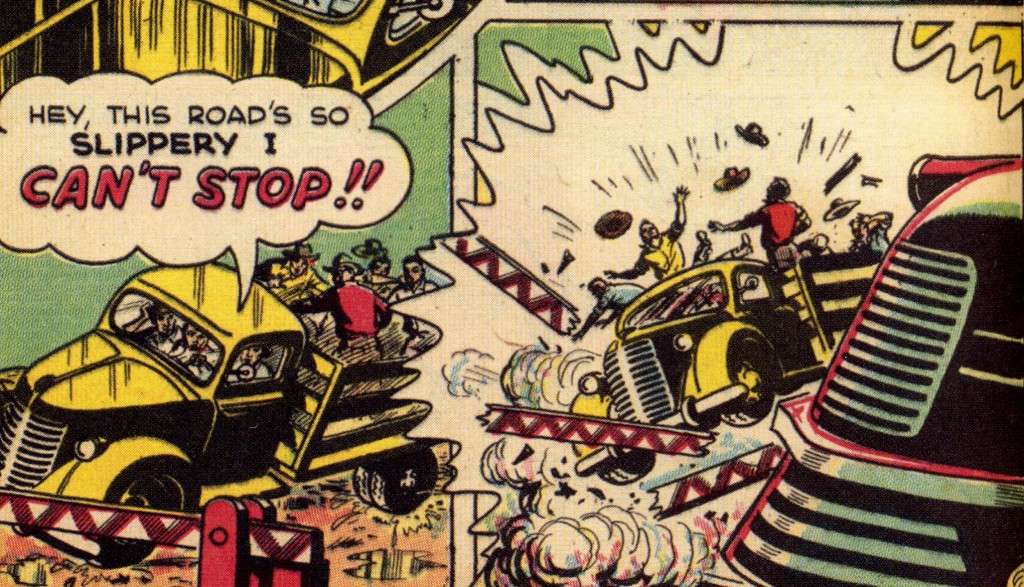

Ed Dodd of Mark Trail fame created Smash Up at Big Rock to promote the importance of Social Security.

There were also government comics about health and safety. For example, Milton Caniff also created Fire Protection in Civil Defense in 1942.

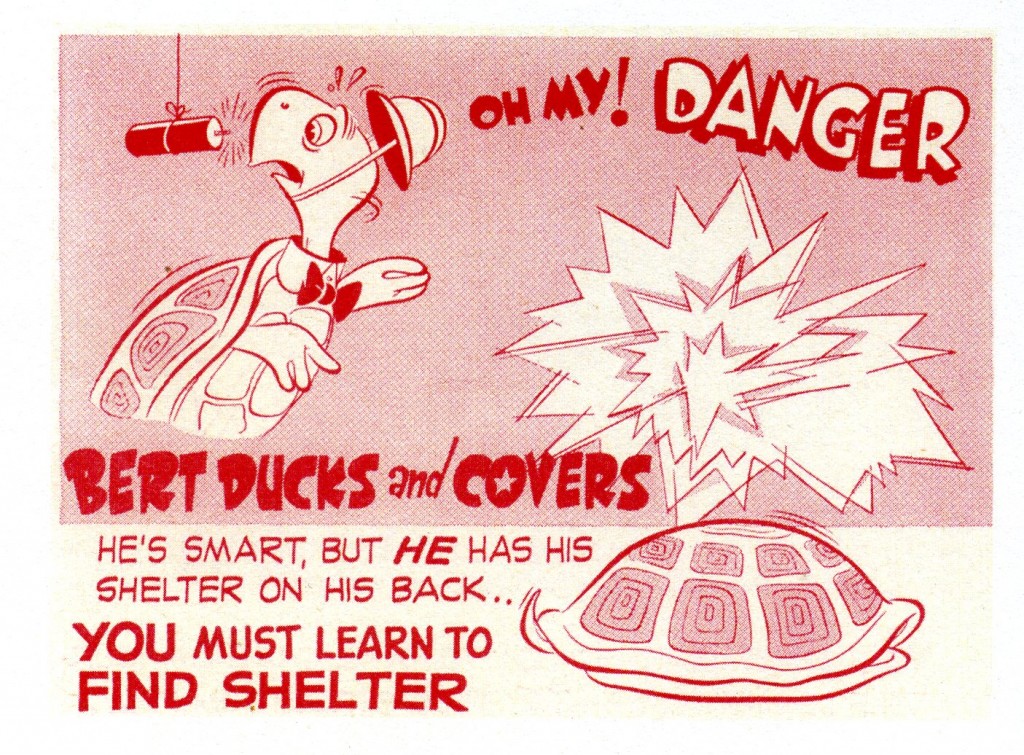

Bert the Turtle told everyone to Duck and Cover from the atomic bomb.

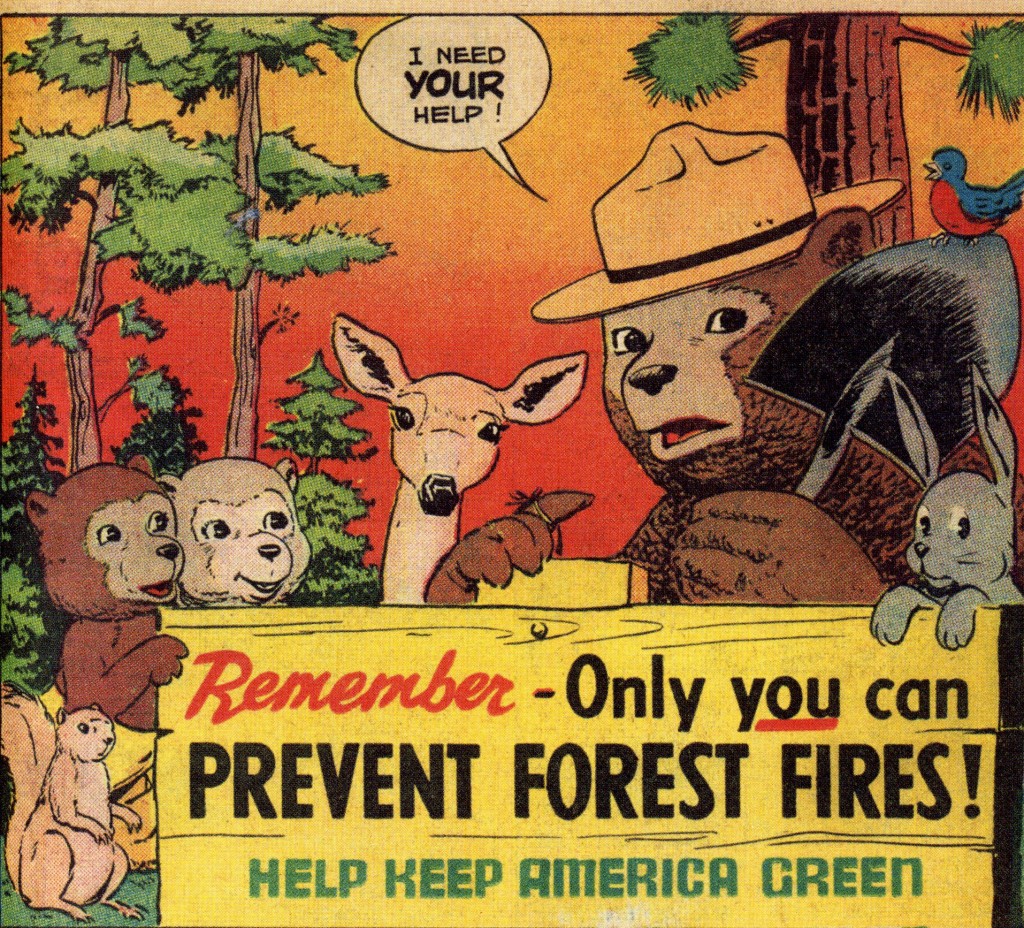

Smokey Bear told us that only we can prevent forest fires. (As an aside, I always thought he was “Smokey the Bear” and, after researching this article, now stand corrected.)

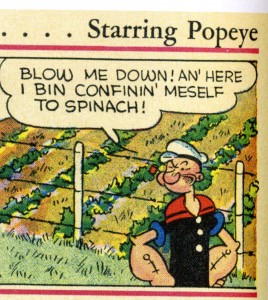

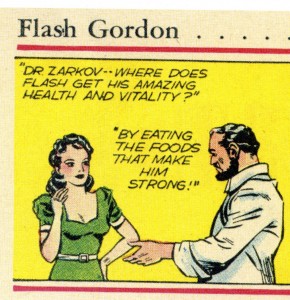

Popeye, Flash Gordon, and the Phantom taught Americans how to Eat Right to Work and Win.

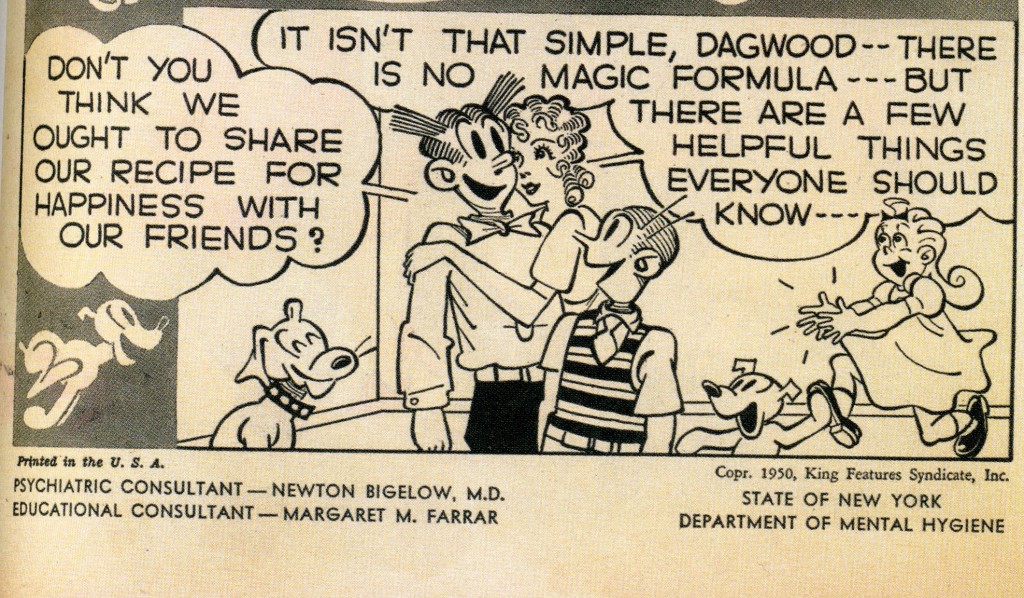

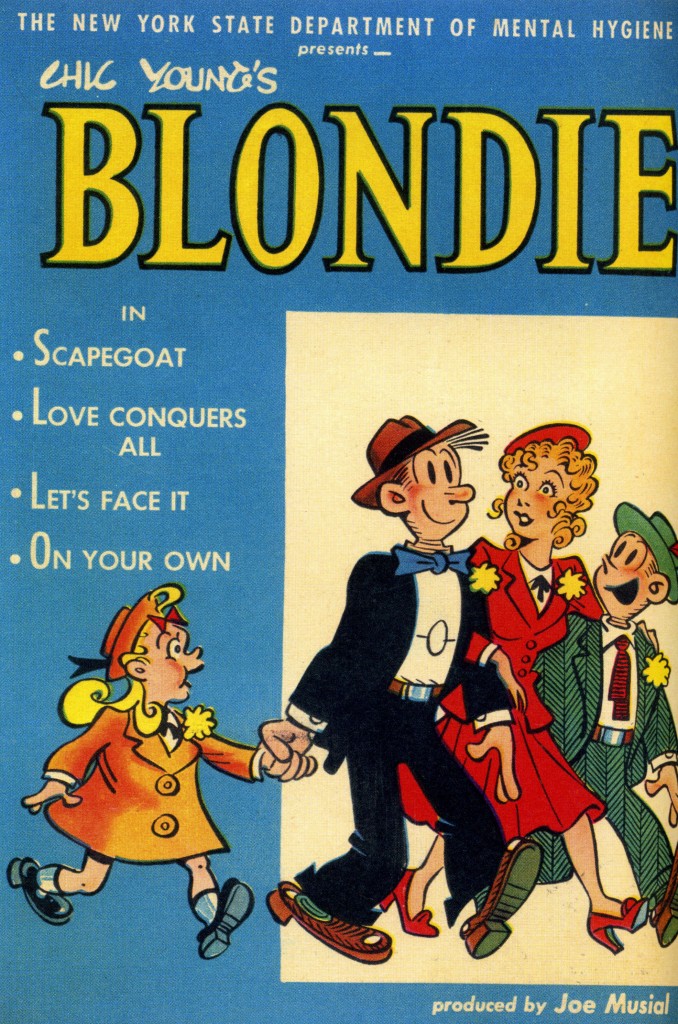

Not be outdone, Chic Young lent out his characters from Blondie to the New York State Department of Health to promote mental hygiene.

Given the growth of government comics before 1954, it appeared that comics as a medium had finally become respected as an effective form of positive communication and art.

Appearances can be deceiving.

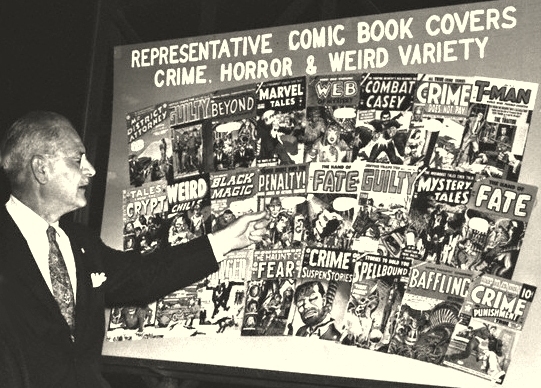

Shortly after World War II and the defeat of Adolph Hitler, Dr. Fredric Wertham helped lead Americans against a new enemy: comic books. Wertham, a German-born psychiatrist, worked in a charitable hospital in Harlem, treating juvenile delinquents. During the course of his work, he discovered that many of these delinquents read comic books. Thus, Wertham concluded, comic books inspired children to become criminals. In 1948, Wertham began his public attack on comics with an interview in Collier’s Magazine called “Horror in the Nursery.” A short time later, he presented at a symposium a report entitled “The Psychopathy of Comic Books.” In May 1948, those same views were released with the same name in the American Journal of Psychotherapy and in the Saturday Review of Literature in an article entitled “The Comics . . . Very Funny” (excerpts would later be included in the August issue of Reader’s Digest). Wertham considered comic book readers to be “abnormally sexually aggressive” and thought that reading comics led to crime. Of course, Wertham wasn’t the first person to have this opinion. But Wertham was a highly distinguished psychologist who thought comic books were bad for kids and eloquently voiced his concerns. The apex of his anti-comics work was the 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, which vilified horror, crime, and superhero comics. All of this caused a public backlash against the comics industry in general. To address this growing problem, the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held hearings in 1954. As part of these hearings, Wertham was asked to testify to a room of sympathetic Senators. He told the committee, “I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.” He made a convincing case.

However, Wertham’s views were not shared by the producers of government comics. Richard Graham writes:

Though Dr. Wertham saw absolutely no value in comic books, even in titles such as Classics illustrated, government entities such as the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) and the New York State Department of Health continued to print them even as comics were literally on trial. . . .The FDCA, meanwhile, recognized that if comics could warn readers about the consequences of bad behavior, they could also be the perfect delivery system for the FCDA’s main message: always be prepared.

As a result of these hearings and publishers’ concerns about government regulation, the comics industry formed the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) in September of 1954 to address the widespread public concern over comic book content. On October 26, 1954, the CMAA adopted the Comics Code Authority and began almost 60 years of self-censorship. In short, the industry formed a self-regulatory body, which would impose and self-police a “code of ethics and standards” for comics. This was done by requiring that each comic book published have a seal of approval.

Still, an examination of the concerns of Wertham and the Subcommittee as compared to the government comics being produced at the time shows that, in addition to having witnesses swear on the Bible, Congress should have probably opened the Book up to Luke 4:23: “Physician heal thyself.”

For example, one of the main concerns of the committee was violence. To prove their point, the Committee reviewed several comics. The second of these was Frisco Mary. On this, the Committee wrote:

This story concerns an attractive and glamorous young woman, Mary, who gains control of a California underworld gang. Under her leadership the gang embarks on a series of holdups marked for their ruthlessness and violence. One of these escapades involves the robbery of a bank. A police officer sounds an alarm thereby reducing the gang’s “take” to a mere $25,000. One of the scenes of violence in the story shows Mary poised over the wounded police officer, as he lies on the pavement, pouring bullets into his back from her submachine gun. The agonies of the stricken officer are clearly depicted on his face. Mary, who in this particular scene looks like an average American girl wearing a sweater and skirt and with her hair in bangs, in response to a plea from one of her gang members to stop shooting and flee, states: “We could have got twice as much if it wasn’t for this frog-headed rat!!! I’ll show him!”

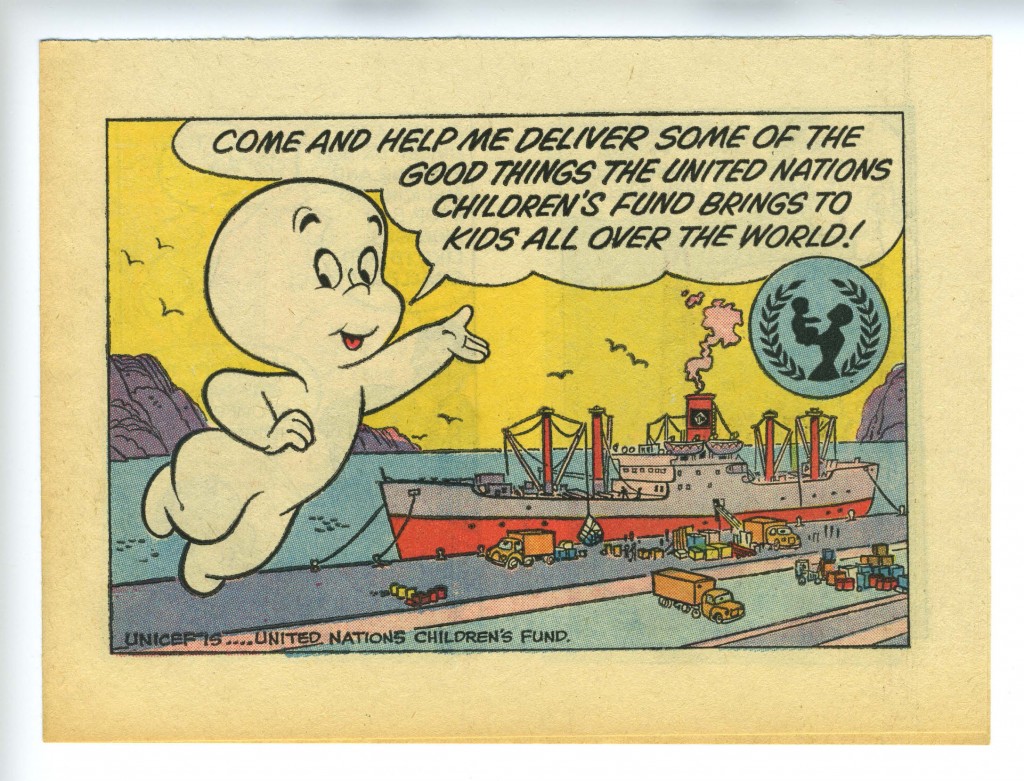

This story was created by Warren Kremer, the writer and artist that created the Harvey Comics characters Richie Rich, Hot Stuff the Little Devil and Stumbo the Giant. Interestingly, at the same time as the committee was condemning Kremer, they were also hiring him (and Harvey Comics) as the letter and Casper cartoon below show.

In fact, in 1954 – 1955, the same years of the hearing and the release of the interim report, the government was busy churning out its own comics, including:

The Youth You Supervise, featuring Li’l Abner:

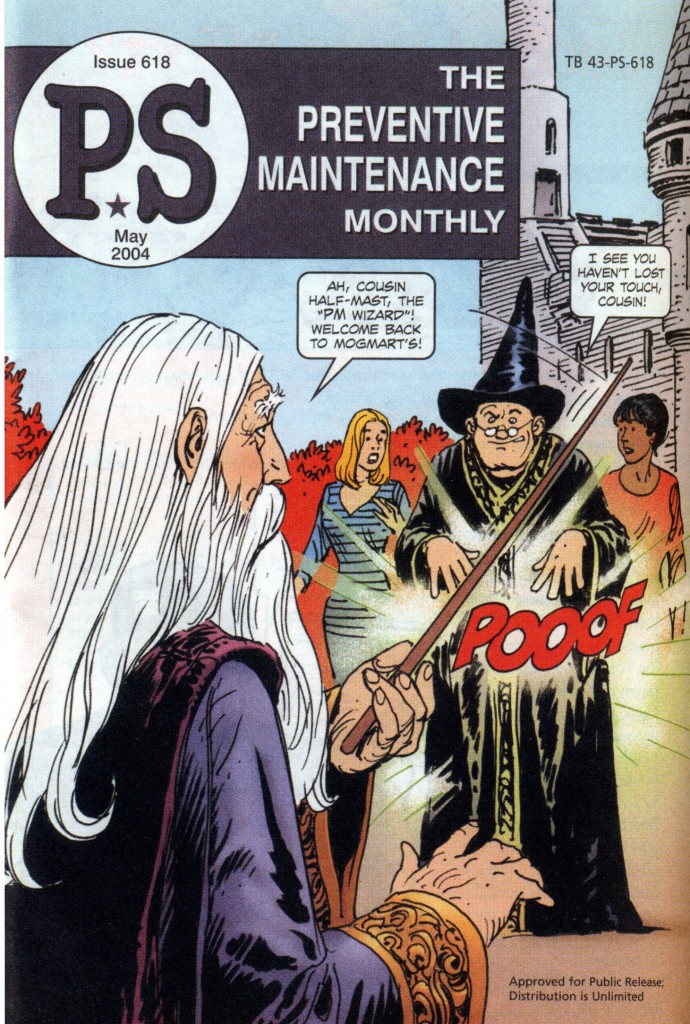

PS Magazine:

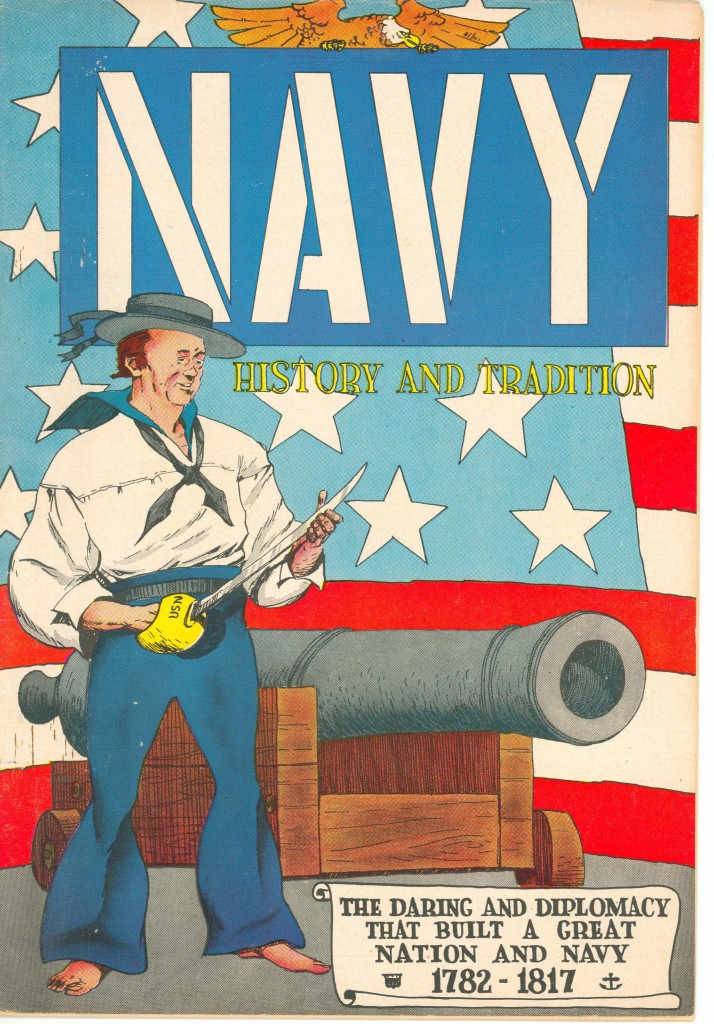

Navy History and Tradition: The Daring and Diplomacy that Built a Great Nation and Navy, 1782-1817

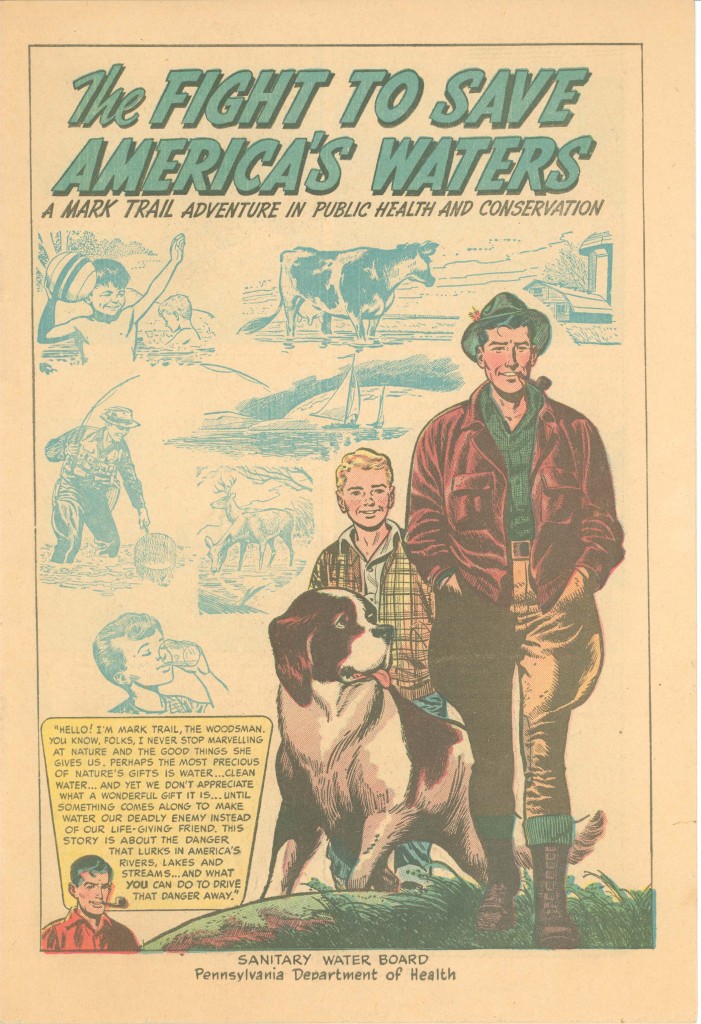

And Mark Trail helped us to save America’s waters:

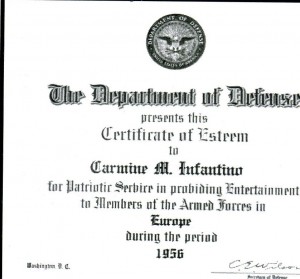

Also at that time, the Army was working with comic artists to entertain the troops at home and abroad. As Carmin Infantino explains in his autobiography:

Sometimes I’d have to get away from work. I loved to travel; it was in my blood. I started traveling with the Cartoonists Society, too. They had tours to Army bases in Europe and in Asia. The Army would give you a GF-17, and they’s ship you over there to draw cartoons for and entertain the soldiers. They were very appreciative; I even received commendations from the Department of Defense. I traveled quite a bit. It actually enhanced my work. It’s inspiring to see other lives and other cultures.

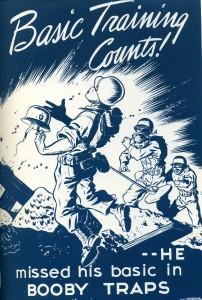

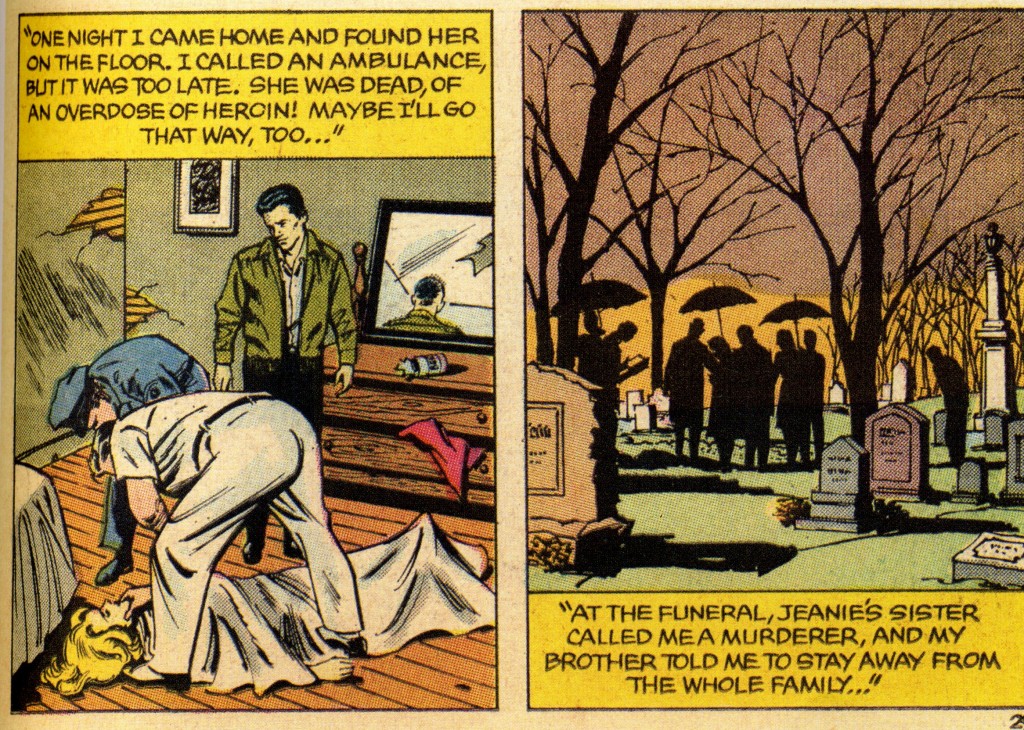

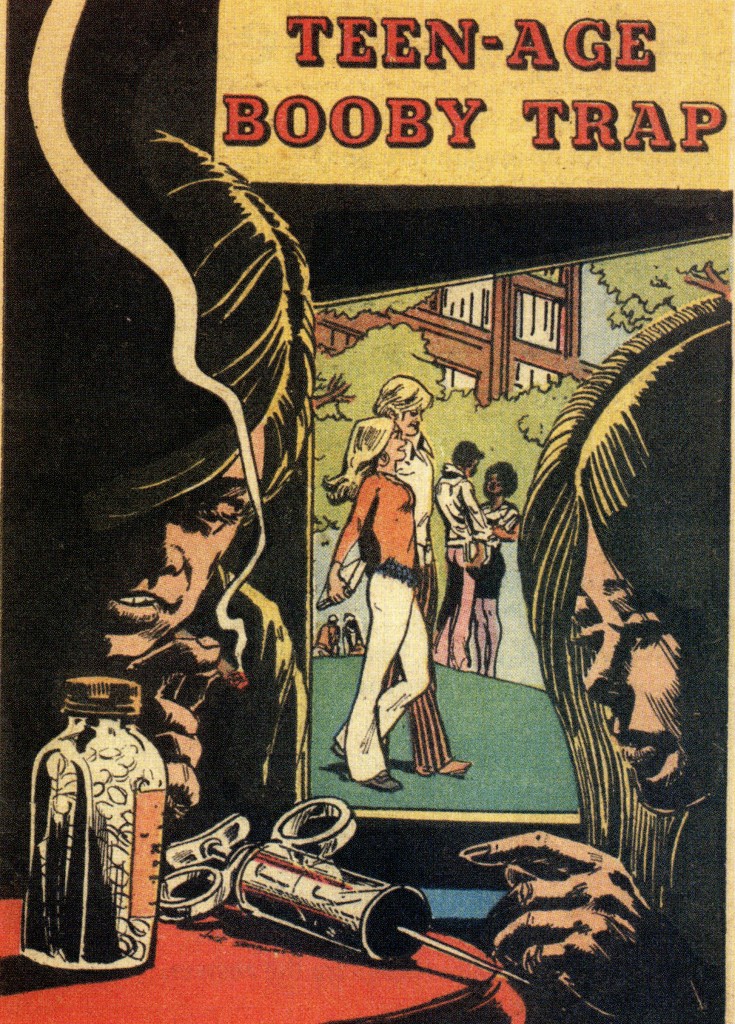

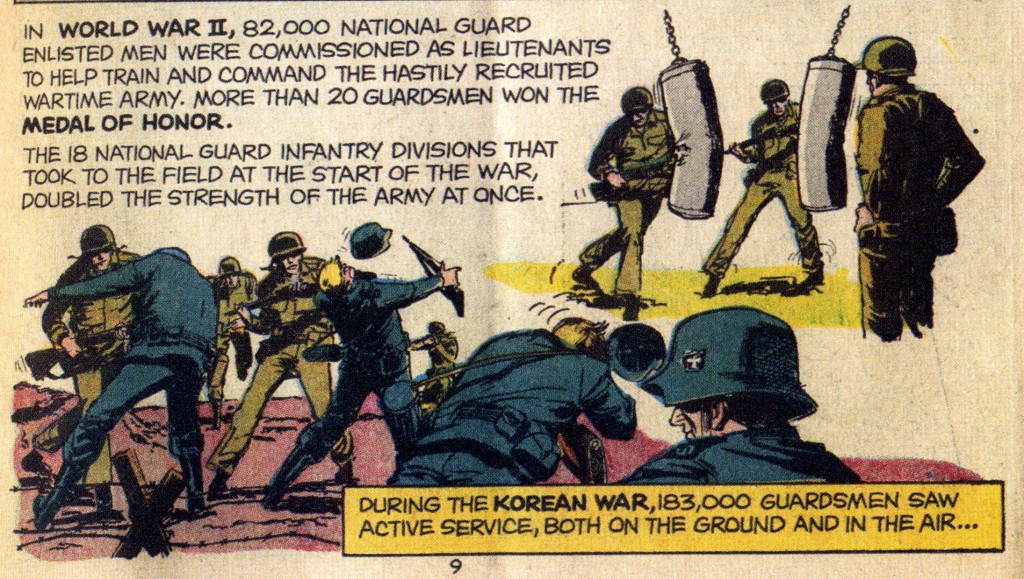

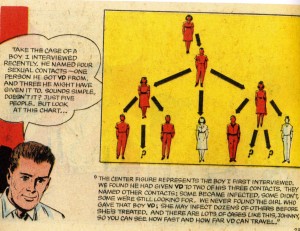

An underlying problem the Committee had with the comics industry was the graphic violence and over the top horrific drawings. Interestingly, here are a sampling of government drug and war comics that are, in many ways, as graphic as any of the books condemned by the Committee. Given that these drug comics predate the Spider-Man drug issues, it is pretty clear that they would have violated the Comics Code Authority.

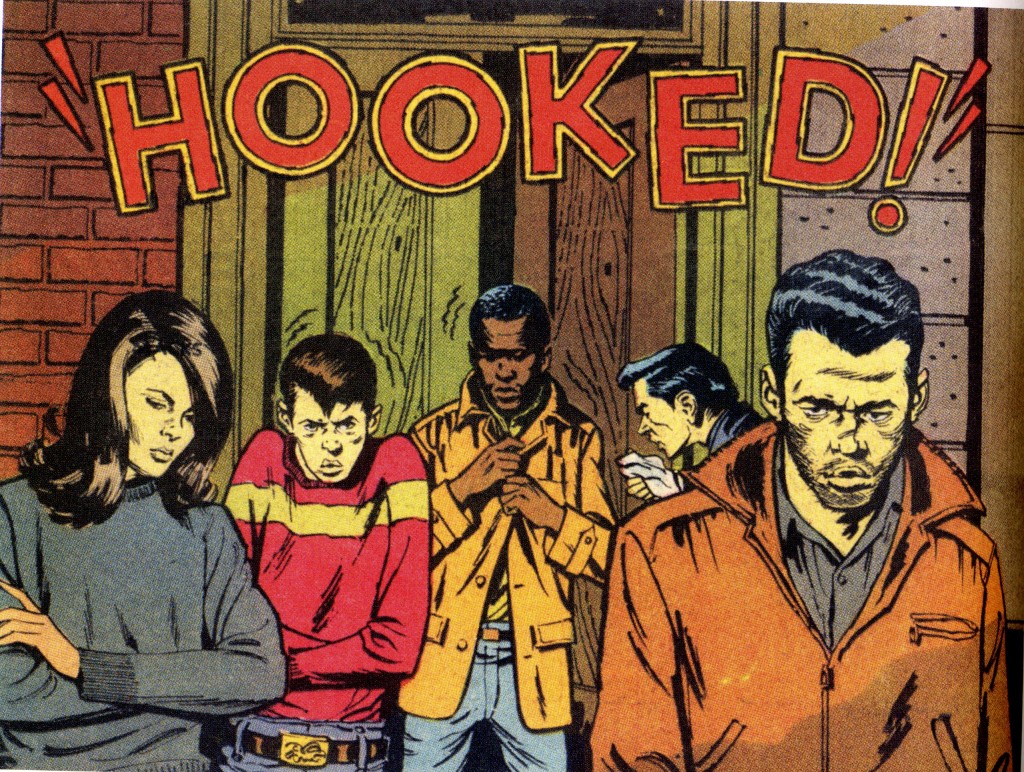

Hooked from US Department of Health Education and Welfare (1967):

Teen Age Booby Trap from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, US Dept of Justice:

Smash-Up at Big Rock from the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Social Security Administration (1958):

I Am the Guard (which features art by the super talented Neal Adams) from Johnstone and Cushing for the National Guard:

The report also had a problem with the use of the supernatural.

One method of portraying horror relates supernatural phenomena with real people and things. In this type of story, horror was portrayed by making use of fantastic supernatural powers and by identifying these powers with people and animals that really exist.

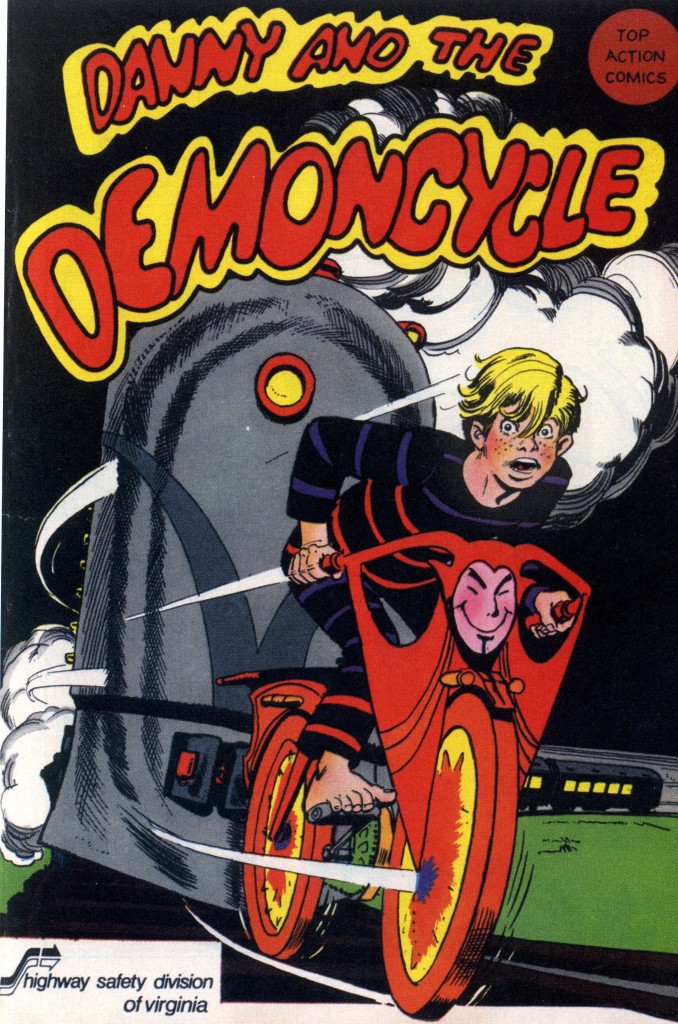

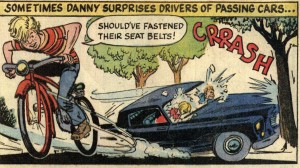

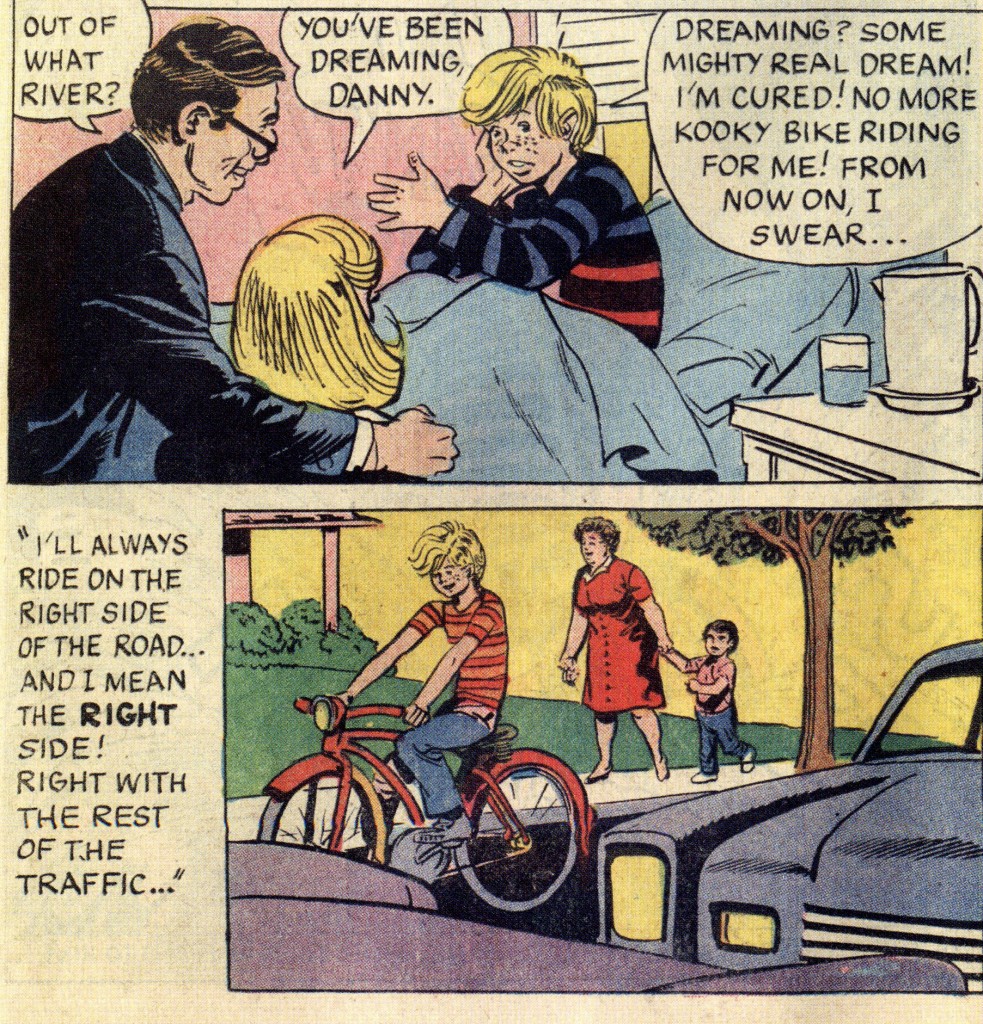

Of course, the Highway Safety Division of Virginia would utilize this same tactic later in Danny and the Demoncycle, written by Jack Sparling (probably most know for his Classics Illustrated work) and drawn by Malcolm Ater (the founder of Commercial Comics). There is an obvious parallel to Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, but I also wondered if poor Danny’s last name was Ketch.

Interestingly, this comic may have also violated the Comics Code Authority, which provided the following guidelines for content:

General Standards Part A states:

3. Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

6. In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

I wonder what Code reviewers would have viewed Danny’s lack of respect for authority when he causes a car accident or hurts an old man.

Not to mention that he doesn’t pay for his crimes.

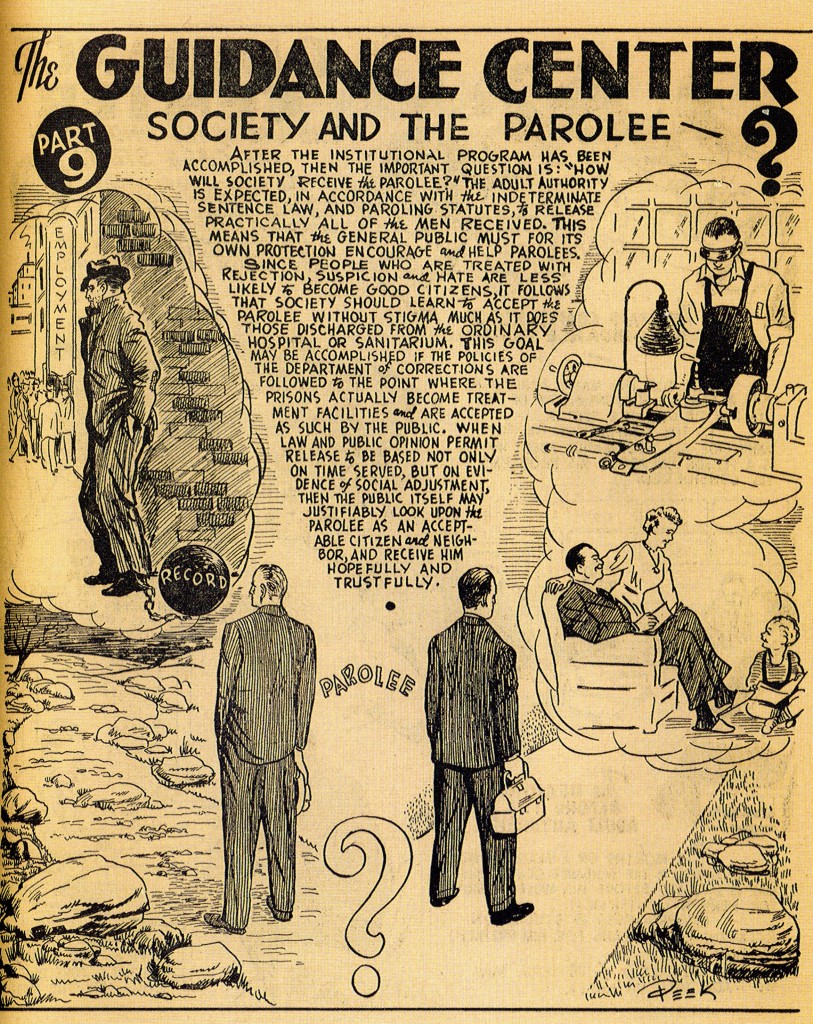

The Committee was also concerned with the fact that comics glorified criminal activity and the fact that criminals could commit their lurid acts and be rewarded. In 1945, the State of California Department of Corrections created a comic that shows the skills that one can develop in prison (the book was drawn by a prisoner named Peek).

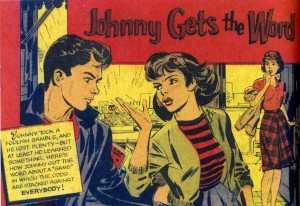

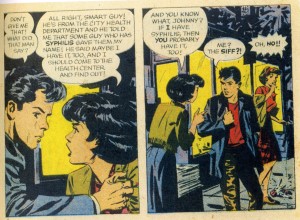

There was also an underlying concern about the way comics portrayed sex outside of marriage. A few years after the hearing, the Health Services Administration in the Department of Health in New York released Johnny Gets the Word, a comic produced in 1957. I wonder what Committee members would have thought when they realized that the “Word” was syphillis. Or in the fact that it implies the numerous sexual partners teens have.

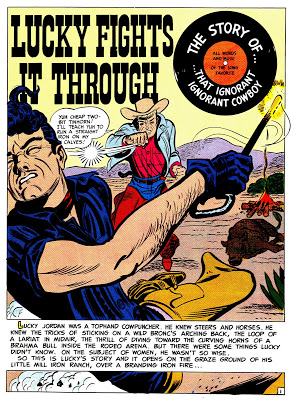

And it should be noted that EC Comics, a clear target of the Committee, produced a similar comic in 1949. David Hajdu, in The Ten-Cent Plague writes:

Kurtzman’s first assignment for EC was the art for an educational pamphlet packaged by the late M.C. Gaines’s brother David . . . . Titled Lucky Fights It Through, the booklet was a Western story about venereal disease — as Kurtzman later described it, “a comic on how to cure syphilis or spot the sores and recognize them, and it came with a little record, ‘The Lonesome Cowboy’ or ‘The Diseased Cowboy,’ something like that. I did such a good job, think of all the people out there who became cured through my comic strip. I don’t know whether it helped cure or helped the sickness, because it showed this guy running around with hookers. It showed how to do it.”

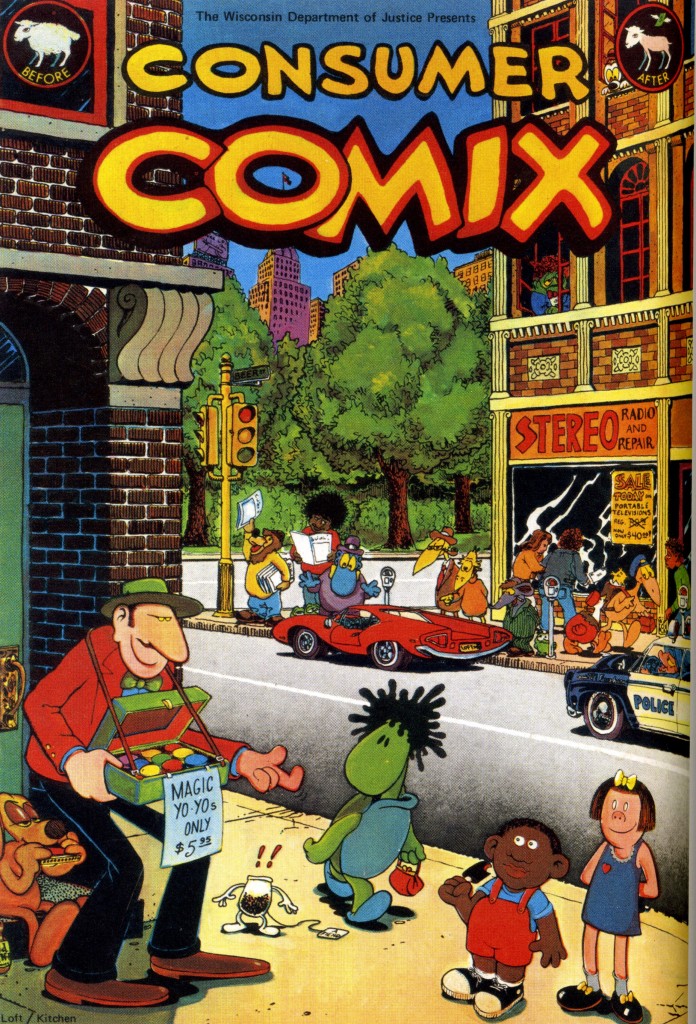

And speaking about sex and government comics, I should also point out that, in 1975, Denis Kitchen, Peter Loft, and Poplaski produced Consumer Comix for the Wisconsin Department of Justice. The title deliberately had the look and feel of the underground comix movement. This was six years after the 1969 raids involving Zap Comix and a decade earlier than the Friendly Franks arrests related to several underground comix (including books by Kitchen) that led to the creation of the CBLDF.

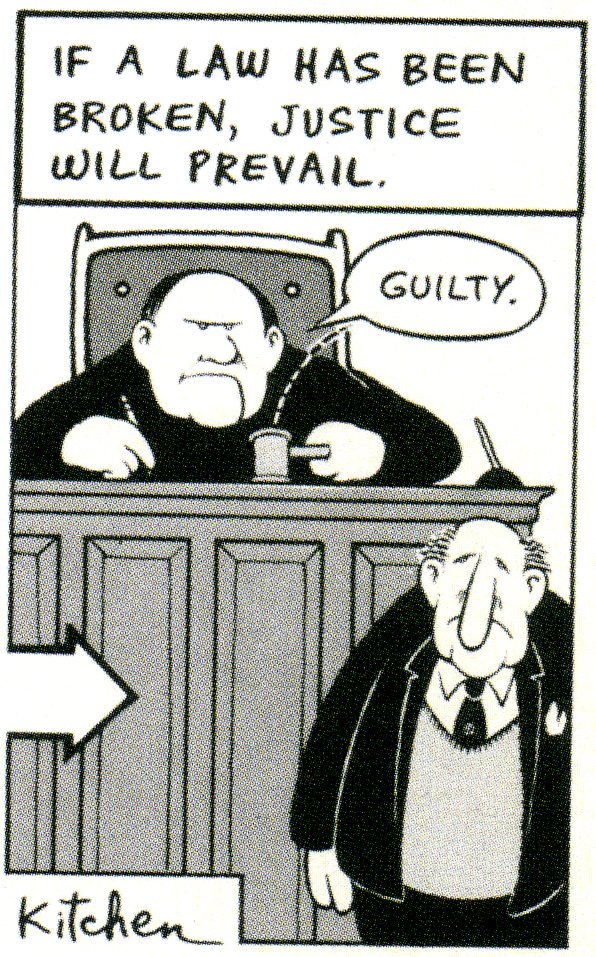

This panel from the book unintentionally foreshadowed the fate for a lot of underground comix:

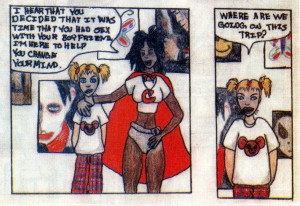

I’m also not sure what CCA would have thought of the Captain Abstinence adventure in Abstinence Comix:

Turning to sexual orientation, in Seduction of the Innocent, Fredric Wertham claimed, “The Batman type of story may stimulate children to homosexual fantasies, of the nature of which they may be unconscious” and “Only someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and of the psychopathology of sex can fail to realize a subtle atmosphere of homoeroticism which pervades the adventures of the mature ‘Batman’ and his young friend Robin.” Presumably, he based his conclusions on panels like this:

I wonder what the good doctor would have thought of these panels from Military Courtesy by artist Al Avison from Harvey Comics.

Of course, as I have previously pointed out: In addition to Batman, Wertham had a huge problem with the other two members of DC Comics trinity: Superman and Wonder Woman. (“This Superman-Batman-Wonder Woman group is a special form of crime comics.”) In essence, Batman was gay, Superman was a fascist, and Wonder Woman was a sadomasochistic lesbian. However, what Wertham ignored was the fact these characters also played a large part in government comics.

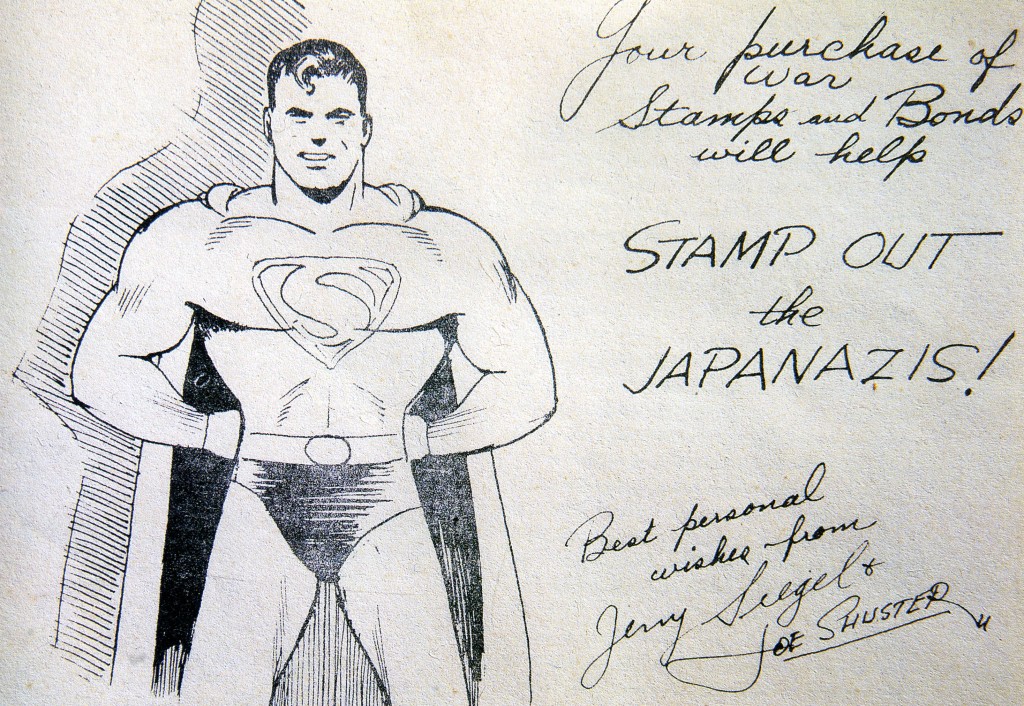

During World War II, Superman sold War bonds.

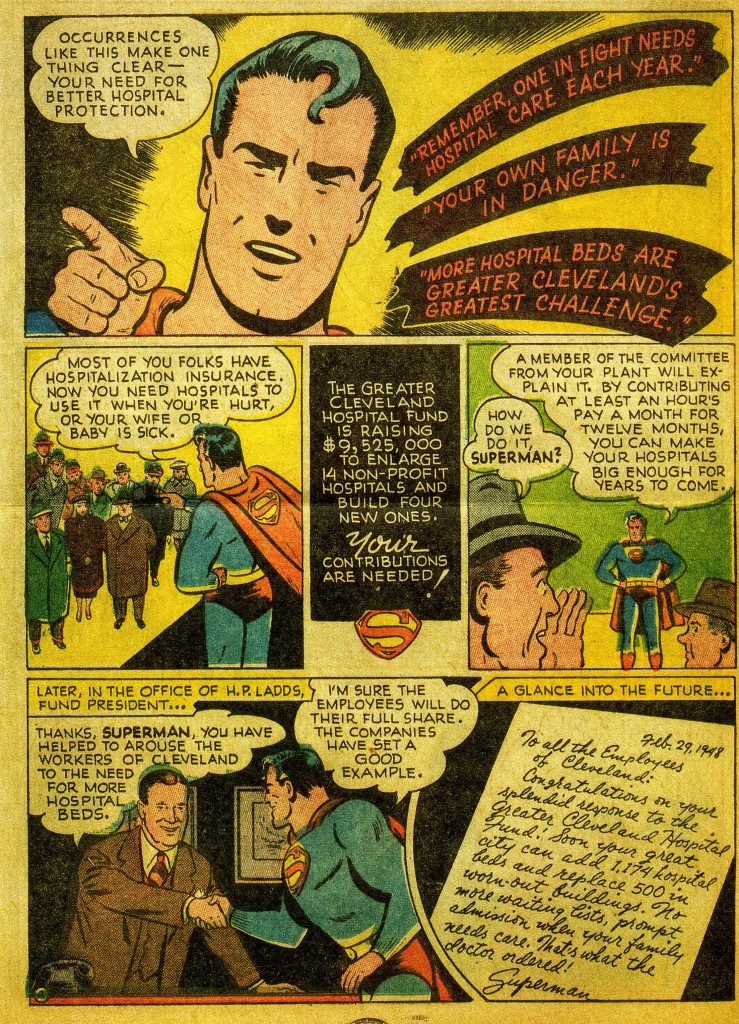

Later, Superman appeared in a four page promotional piece for the the Cleveland Hospital Fund entitled Superman and the Great Cleveland Fire in 1948.

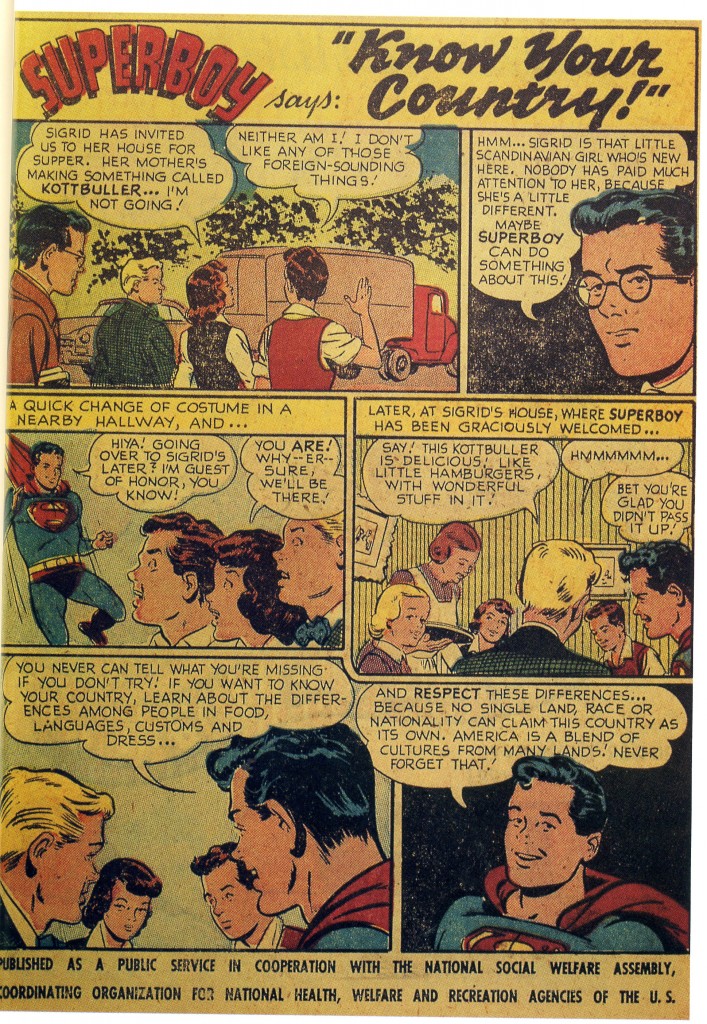

And Superboy appeared to teach a lesson in tolerance on behalf of the National Social Welfare Assembly.

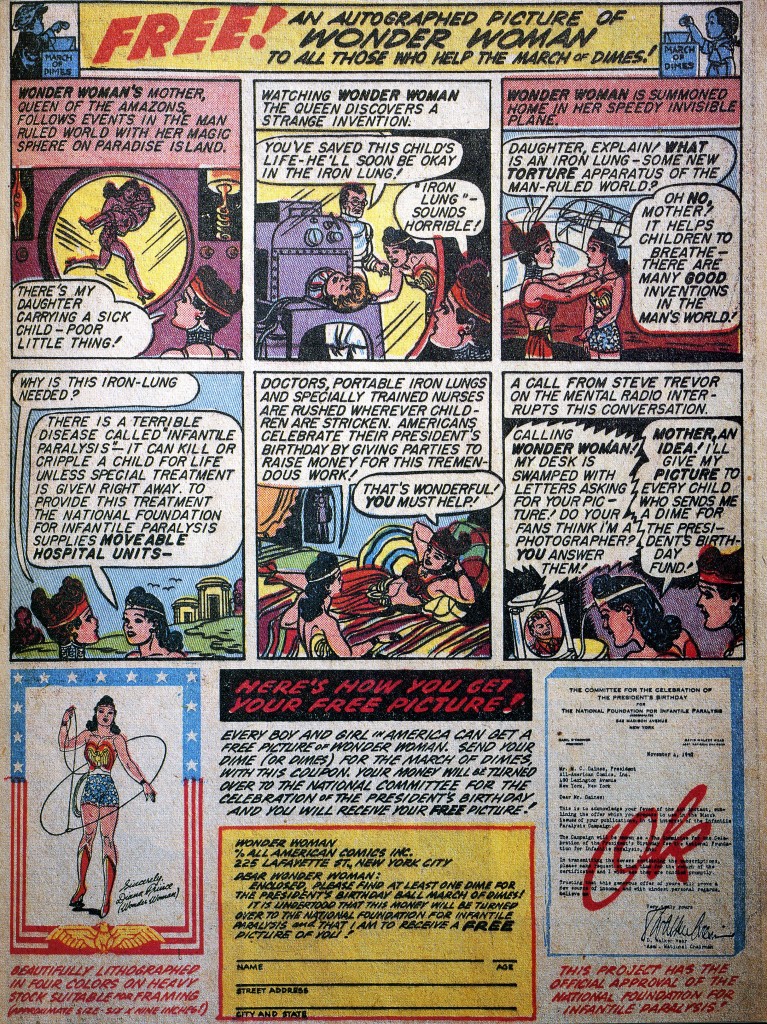

Wonder Woman worked with the March of Dimes to help the National Committee for the Celebration of the President [Roosevelt’s] Birthday. For a dime, donors got an autographed picture of the Amazonian princess.

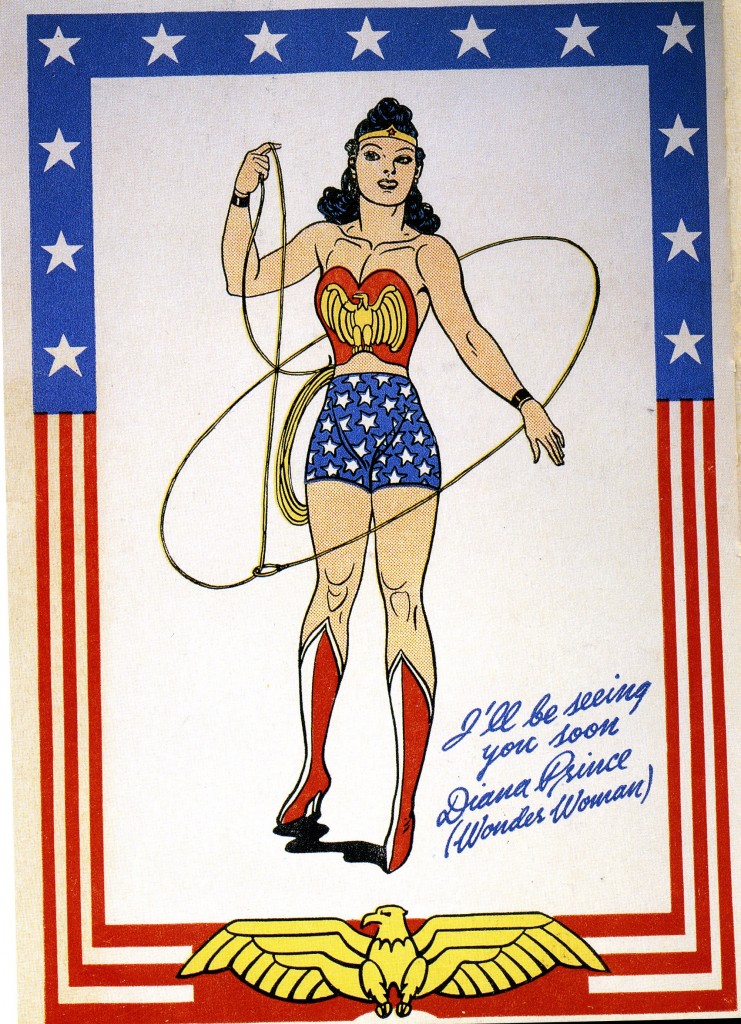

By the way, here is the picture you received for your donation:

DC also assisted the government comics movement, as they touted their good works in the following ad.

I don’t want to leave the impression that the 1954 hearings ignored the existence of these types of books. To be fair, the Committee did address the issue of government comics. The Committee stated:

Crime and horror comic books constitute but a segment, although quite a substantial segment, of the total comic-book industry in the United States. There are some publishers in this field who have not produced crime and horror comic books and do not intend to do so. The members of the subcommittee were particularly interested in certain aspects of the industry which relate to communication, education, and public opinion. In those areas, it appears that there are possibilities for positive contributions.

To further this goal, the Committee heard from Joseph W. Musial, educational director of the National Cartoonists Society; Walt Kelly, president of the National Cartoonists Society; and Milton Caniff, artist. Musial testified about his work with the state of New York in producing Blondie comics for the state’s mental hygiene campaign.

The interim report concludes:

After hearing the presentation of Mr. Musial, Mr. Kelly, and Mr. Caniff to the effect that government and private agencies and philanthropic organizations have recognized the comic book as an effective medium of communication for worthwhile objectives, it is apparent too that the comic book can also be an effective medium of for unworthy objectives. The comic book is recognized as a means of publicizing crime and horror. There was no plausible reason offered as to why this medium should be less impressive when dealing with one kind of subject matter than with another.

Of course, the Committee also concluded:

The consensus is that the comic art has genuine appeal for a large segment of the American public. It is apparent that comic books have assumed major importance in the reading diet of thousands of American youths. For that reason, it is important that the artwork be of a high level.

Still, comics have not only survived, but thrived. And government comics are still produced today. In fact, corporate America has also gotten into the act. As a result, and perhaps in accordance with the Committee’s mandate that “artwork be of a high level,” these government and PSA comics have greatly increased in quality over the years. Here is a sampling of the more recent comics.

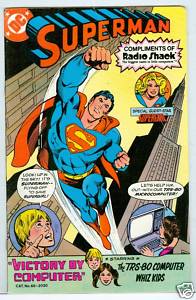

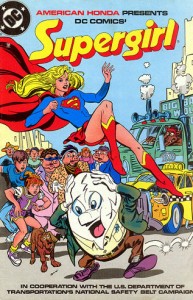

Supergirl tells us to wear our seatbelts when she is not helping her cousin explain the importance of electronics and computers:

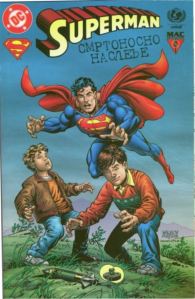

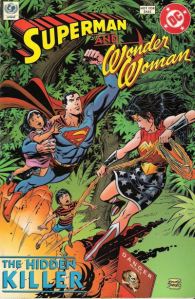

Superman is pretty busy himself explaining the danger of landmines, with and without Wonder Woman. As Larry Tye explains:

Also in were causes to which DC thought that Superman could be of service. that was the case in 1996 when it collaborated with the Defense Department and UNICEF in publishing a special comic book in which Superman swept down and saved two boys about to step on a landmine. The safety lessons were written in Serbo-Croatian, printed in both the Cyrillic characters used by the Serbs and the Roman ones used by the Muslims and Croats, and half a million of the comics were shipped to Bosnia and Herzegovina. More of the same lessons, in Spainish, would be shipped to war zones in Central America. Why Superman? “He’s a citizen of the world,” explained Jenette Kahn.

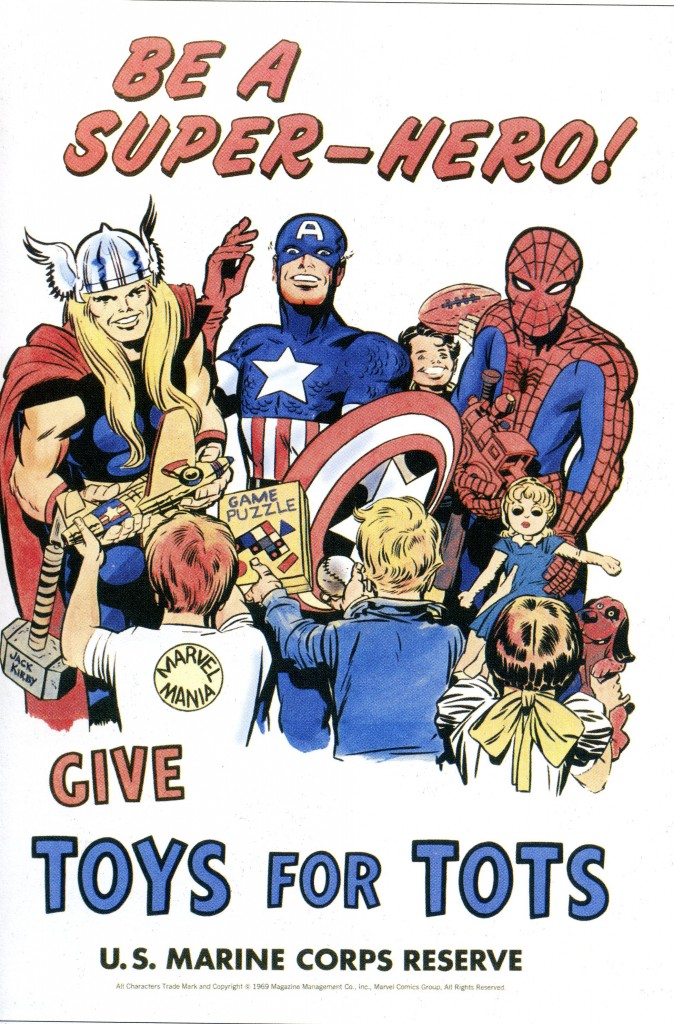

The amazing Jack “King” Kirby drew this poster for Marvel to support the US Marine’s Toys for Tots program.

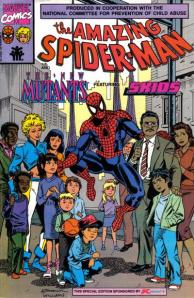

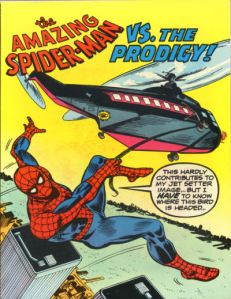

Spider-Man has done comics with the government about everything from child abuse to STDs.

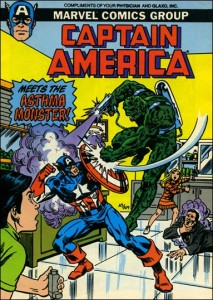

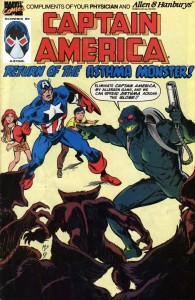

Daredevil fought Vapora while Captain America fought asthma — twice. (Did you know that Steve Rogers was an asthmatic?)

DC Vertigo’s Death warned us about AIDS.

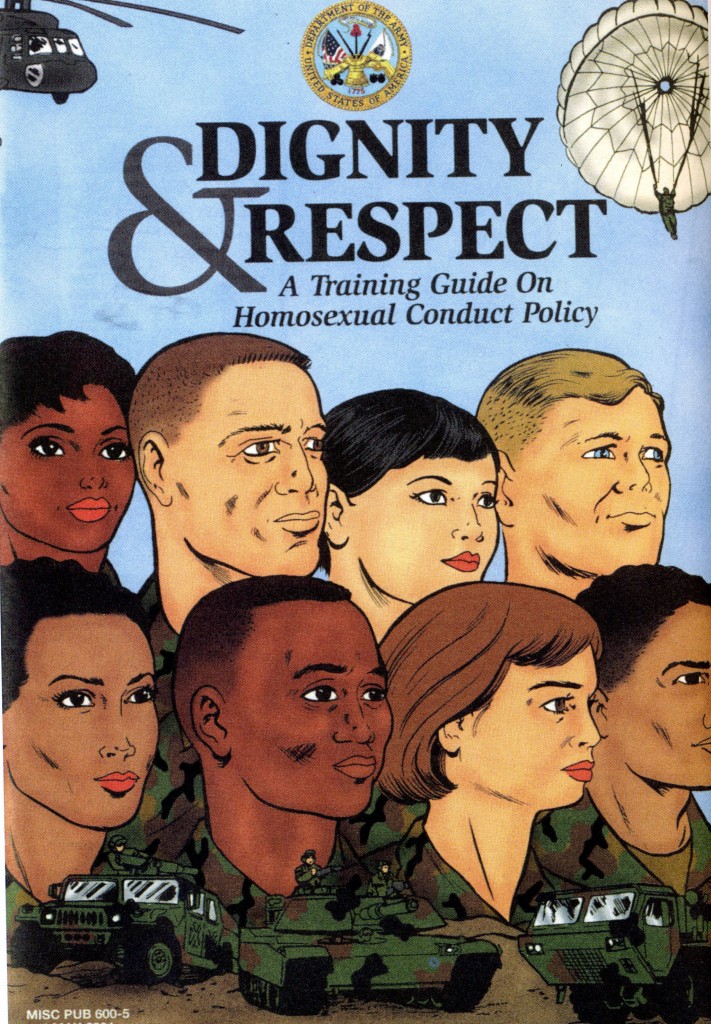

The Army produced a “Don’t ask. Don’t Tell” comic.

They also got in trouble for ripping off Harry Potter in a book drawn by the incomparable Joe Kubert.

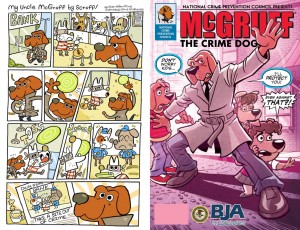

Smokey Bear has been joined by Woodsy the Owl and McGruff the Crime Dog.

And the Teen Titans (sans Robin because licensing disputes the books were sponsored by Keebler and Robin was licensed to Nabisco) joined First Lady Nancy Reagan in her campaign to “Just Say No!” to drugs in a series of books written by Titans Dream Team of Marv Wolfman and George Pérez. (There was also an animated commercial). As an interesting aside, the Protector (the original character of the book created to replace Robin), also appeared in continuity in Teen Titans Secret Files #2 and the Infinite Crisis hardcover and is acknowledged as an official Titan in DC’s Who’s Who series.

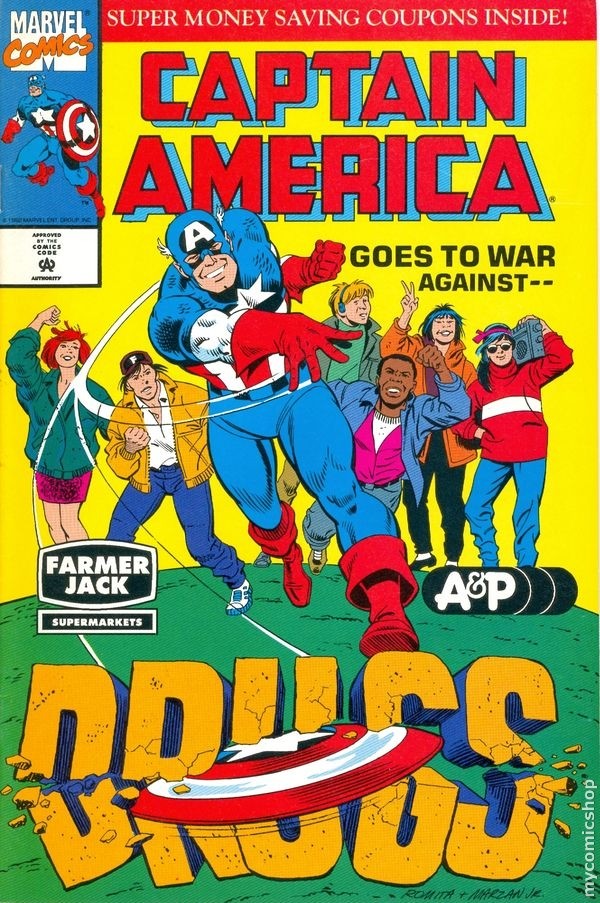

And since, the theme of this post is irony, I should end it with the time Captain America went to war against drugs.

The fact that Cap, himself, owes his powers to being injected with a Super Soldier Serum, is not a black fly in your Chardonnay, but it is certainly ironic. I wonder if the sequel will be a team-up with Hour Man. But I digress.

After the Committee released its conclusions, the comics industry would never be the same. The Code was created; horror and war comics vanished; and many people looked at comics as nothing more than kids books with no redeeming social value. Sid Jacobson, in the Foreword to Government Comics, makes this observation:

However, librarians everywhere had no use for comics of any kind, and they were banned from school and public library shelves. It was decided that neither the message nor the medium of comics was acceptable — despite the fact that federal and state government agencies continued printing them! For the most part, all the good that comics could bring was forgotten and locked behind a door.

So, in essence, by trying to protect its citizens, the hearings had the opposite effect. For a time, the power of the government comic had been lessoned. Thankfully, it was only temporary.

If you are interested in reading complete copies of any of the government comics in this article or seeing what else the government has produced, check out the government comics collection (administered by Richard Graham) at http://contentdm.unl.edu/cdm/search/collection/comics or pick up his book, Government Issue, Comics For the People, 1940s-2000, from Abrams ComicsArts, both of which were incredibly helpful in preparing this post.

Please help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work and reporting on issues such as this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Joe Sergi is a life-long comics fan and author who has written short stories, novels, comics, and articles in the horror, science fiction, super hero, and young adult genres. When not writing, he works as a Senior Litigation Counsel in an unnamed US government agency. More information can be found at http://www.joesergi.net/.