London’s Shubbak Festival is a biennial celebration of contemporary Arab culture that spotlights film, music, visual, and more with programming and events. One of the programs included in the 2015 edition of the festival, which took place in July, focused on Arab comic art. Panelists Asia Alfasi (Lybia), Lena Mehraj (Lebanon), Tarek Shahin (Egypt), and Mohamed Anwar (Egypt) discussed their work and the obstacles they face in making and distributing it. Among the latter: censorship.

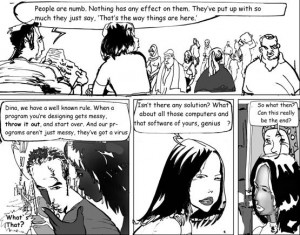

The panelists discussed Magdy al-Shafee’s Metro, a noir tale of software developers struggling against a fundamentally corrupt economy and government under Hosni Mubarak’s regime. Released in 2008, the book quickly gained notoriety when it was banned by the Egyptian government, and al-Shafee was fined for “infringing upon public decency.” Al-Shaffee vowed at the time to fight both the banning and the fine:

Shafee told Daily News Egypt that he was aware that sections of Metro — which contains limited content of a sexual nature — might offend some readers and that it was for this reason that a “for adults only” warning was put on the front cover. Shafee added that the comic’s content does not mean that it should be removed from the market.

“It is unethical to suppress freedom of speech and take books off the market,” Shafee said. “This is about more than ‘Metro.’ If we stay passive we will lose our rights.”

None of the panelists had faced similar persecution by their governments, but they spoke about backlash they faced from their colleagues. From Soraya Morayef at Middle East Eye:

While none of the panellists had similar experiences, Anwar said he recently faced a bitter backlash from his colleagues at the state-run Roz al-Youssef magazine after he made a cartoon of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Such was their vitriol that their complaints gained enough momentum to reach the media and even the presidency, but without any repercussions for the artist.

“For me, what was extraordinary was that this action didn’t come from the government; it came from fellow journalists,” he said after the panel. “I think they did this because of the country’s current state of mind. These are the people that we have to talk to now [as artists].”

The Egyptian government has been especially hard on artists, from al-Shafee to street artists. Many cartoonists in the country have faced a difficult decision: choose free expression or mainstream distribution, but not both. Unfortunately, this means that many cartoonists will self-censor rather than express themselves the way they would like. Shahin admitted that he engaged in self-censorship while creating his political cartoon al-Khan in order to avoid governmental persecution:

“None of my work was ever censored [by the state] but not for lack of trying by the powers that be,” he said. “Credit goes to my editor, who always fought on my behalf. I just didn’t want to give them excuses to arrest me, and that was a reason for my series’ longevity.”

Read more about the panel here. For more on how political cartooning has changed in Egypt, see our previous posts:

- Comic Spring in the Arab World

- Egyptian Humor Fuels Revolution

- Political Cartoonists in Egypt Face Growing Attacks

- Holding Strong Against the Rise of Censorship in Egypt and Tunisia

- Egyptian Woman Cartoonist Won’t Be Silenced

- Cartoonist Keeps Drawing Despite Fundamentalist Threats

- Indie Comics Reborn in Egypt

- Egypt Cracks Down on Street Art

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2015 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!