Happy Women’s History Month! All through March, we’ll be celebrating women who changed free expression in comics. Check back here every week for biographical snippets on female creators who have pushed the boundaries of the format and/or seen their work challenged or banned.

Barbara Hall

Isabelle Daniel Hall, who later worked under the name Barbara, was born in Tucson, Arizona in 1919. After attending art school in Los Angeles, where she studied painting, she moved to New York City in 1940. The next year she was hired by Harvey Comics to contribute penciling and inks for the Black Cat, a crime-fighting heroine with the tagline “Hollywood’s glamorous detective star.”

Isabelle Daniel Hall, who later worked under the name Barbara, was born in Tucson, Arizona in 1919. After attending art school in Los Angeles, where she studied painting, she moved to New York City in 1940. The next year she was hired by Harvey Comics to contribute penciling and inks for the Black Cat, a crime-fighting heroine with the tagline “Hollywood’s glamorous detective star.”

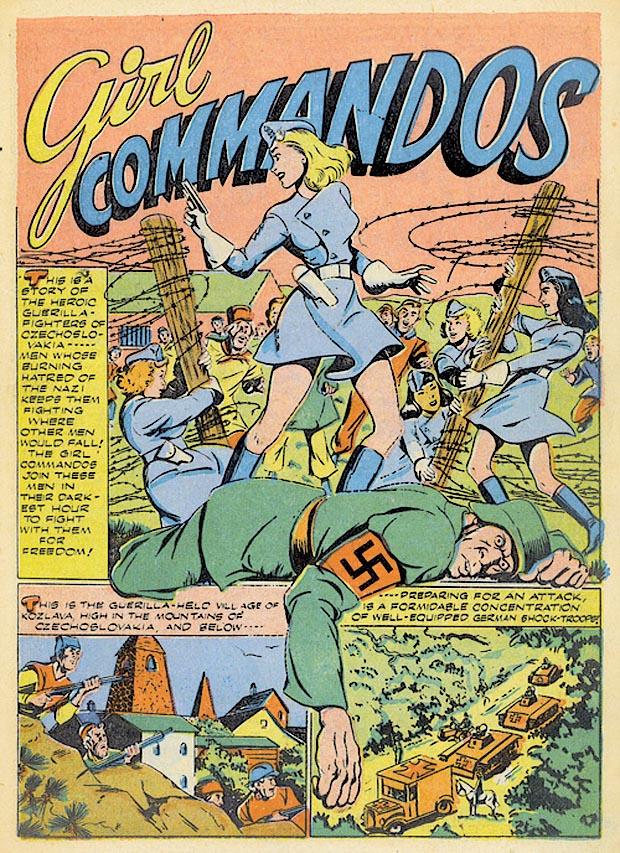

Hall soon earned a more high-profile role as the main artist for the Girl Commandos, an international team of Nazi fighters led by Pat Parker, War Nurse. Aside from being one of the first all-female teams in comics, the Girl Commandos were notable for their relative diversity in body type – Pat Parker’s fellow Brit Ellen Billings was depicted as overweight and eminently capable – and ethnicity, with Chinese member Mei-Ling joining the team early on. The team appeared in several issues of Speed Comics until 1946, but Hall passed off art duties to Jill Elgin in 1943.

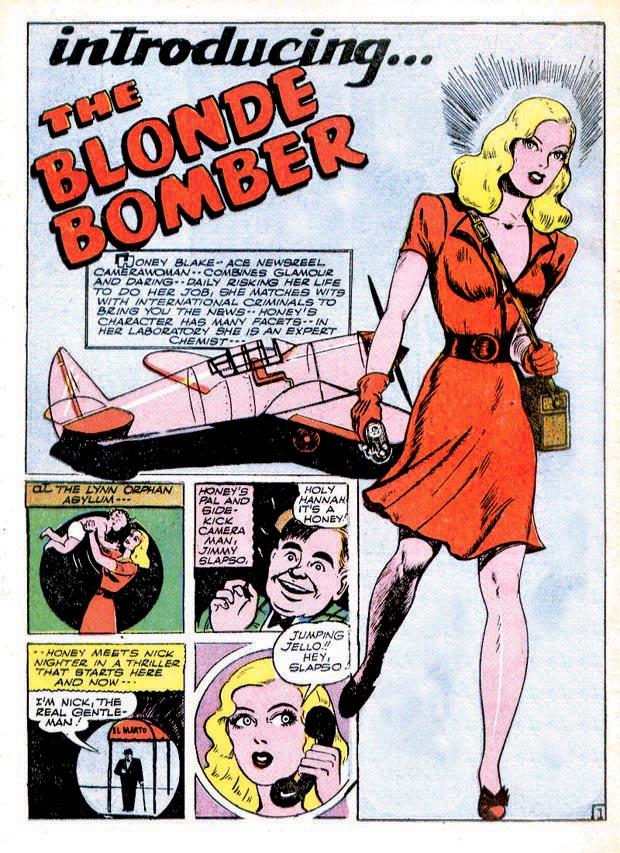

In 1942 Hall also created the character Honey Blake, AKA the Blonde Bomber, who primarily appeared in Green Hornet comics. Blake was an improbable combination of newsreel camerawoman, expert chemist, and crime-fighter along with her sidekick Jimmy Slapso.

In 1946 Hall married writer Irving Fiske and left comics to concentrate on oil painting. The couple retreated to a 140-acre farm in Vermont called Quarry Hill, which they later turned into an artists’ commune. At its peak, the Quarry Hill Creative Center was home to about 90 people, but it still has about two dozen full-time residents. Hall and Fiske divorced in the 1970s, but both continued to live at Quarry Hill, often hosting comics legends such as Art Spiegelman and Robert Crumb. Hall died in 2014 at the age of 94.

–by Maren Williams

Ethel Hays

“A real feather in the feminist’s cap.” This is how one newspaper described cartoonist Ethel Hays in a 1928 article — a description that to this day remains an apt portrayal of the can-do woman who would not only become one of the most prolific commercial artists of the early 1900s, but whose works would epitomize and capture the nuances of a new generation of young, strong, and classy women coming into their independence in the 1920s.

“A real feather in the feminist’s cap.” This is how one newspaper described cartoonist Ethel Hays in a 1928 article — a description that to this day remains an apt portrayal of the can-do woman who would not only become one of the most prolific commercial artists of the early 1900s, but whose works would epitomize and capture the nuances of a new generation of young, strong, and classy women coming into their independence in the 1920s.

Born in 1892 in Billings, Montana, no one ever doubted Hays’ incredible latent talent. The illustrations that she drew for her high school newspaper, the art classes she led for wounded WWI veterans, and the numerous art school scholarships she was awarded saw Hays being recognized by major institutions and newspaper publishers from Los Angeles to New York City.

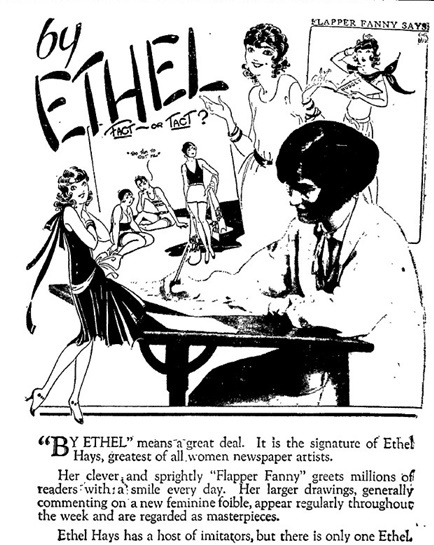

From 1923 to the 1950s, Hays would contribute to some of the most popular strips, producing some of the most iconic cartoons in print. Vic and Ethel (later just Ethel), Flapper Fanny, Femininities, and Maryanne were just a few of the cartoons on which Hays worked, and many appeared in daily newspapers alongside each other. Within her first year of syndication for the Newspaper Enterprise Association syndicate, it is estimated that Hays’ work appeared in over 500 newspapers — a staggering presence for any cartoonist of the time.

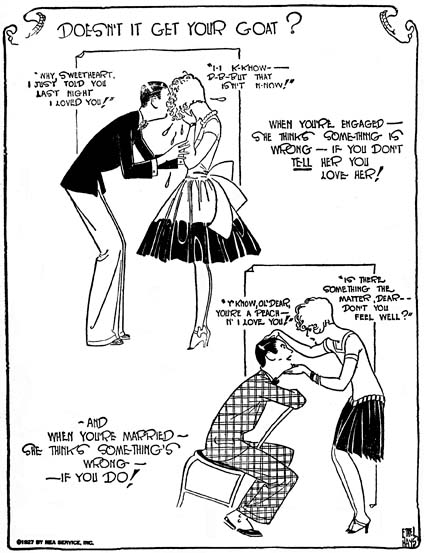

Her saucy wit, playful sense of humor, and knack for commenting on the lives of young American women made Hays an outstanding writer. But it was her clean-lined, full of energy, art-deco inspired artwork that really captured the eyes of all readers. Regardless if you were a man or a woman, you were reading Hays’ work. While young ladies casually pursuing Hays’ Flapper Fanny cartoon everyday, basking in what it meant to be a newly independent woman of the world, young men scrabbled through the cartoons to find out the secrets of the independent women they were trying to court. “Hays’ combination of superb artwork and comedic sensibilities added up to a formula that few female cartoonists of the time could claim,” writes Tom Heintjes. “She created a feature popular with both men and women.”

In the late 1940s and 1950s, though, when the comics industry came under attack by Seduction of the Innocent author Dr. Fredrick Wertham and the anti-comics crusade was in full force, Hays saw an opportunity to retire from her editorial work, but not cartooning entirely. Ever the resourceful and driven woman, Hays would go on to illustrate educational children’s books, coloring books, and even paper doll cut-out books until her death at the age of 97 in 1989.

In a time when women cartoonists were given only two genres to work within—cute animal stories or romance cartoons—Hays showed the cartooning world that even within these boundaries women could be exceptional and overcome gender biases. Although she was influenced by other women cartoonists like Nell Brinkley, Hays’ fluid art style and independent voice, in turn, influenced whole new generations of cartoonists, both women and men. As Heintjes notes:

Ethel Hays worked in the era’s standard female genres yet rose above them. Her talent for cartooning was so great that her work had universal appeal even while working well within the accepted limitations.

–by Caitlin McCabe

Rose O’Neill

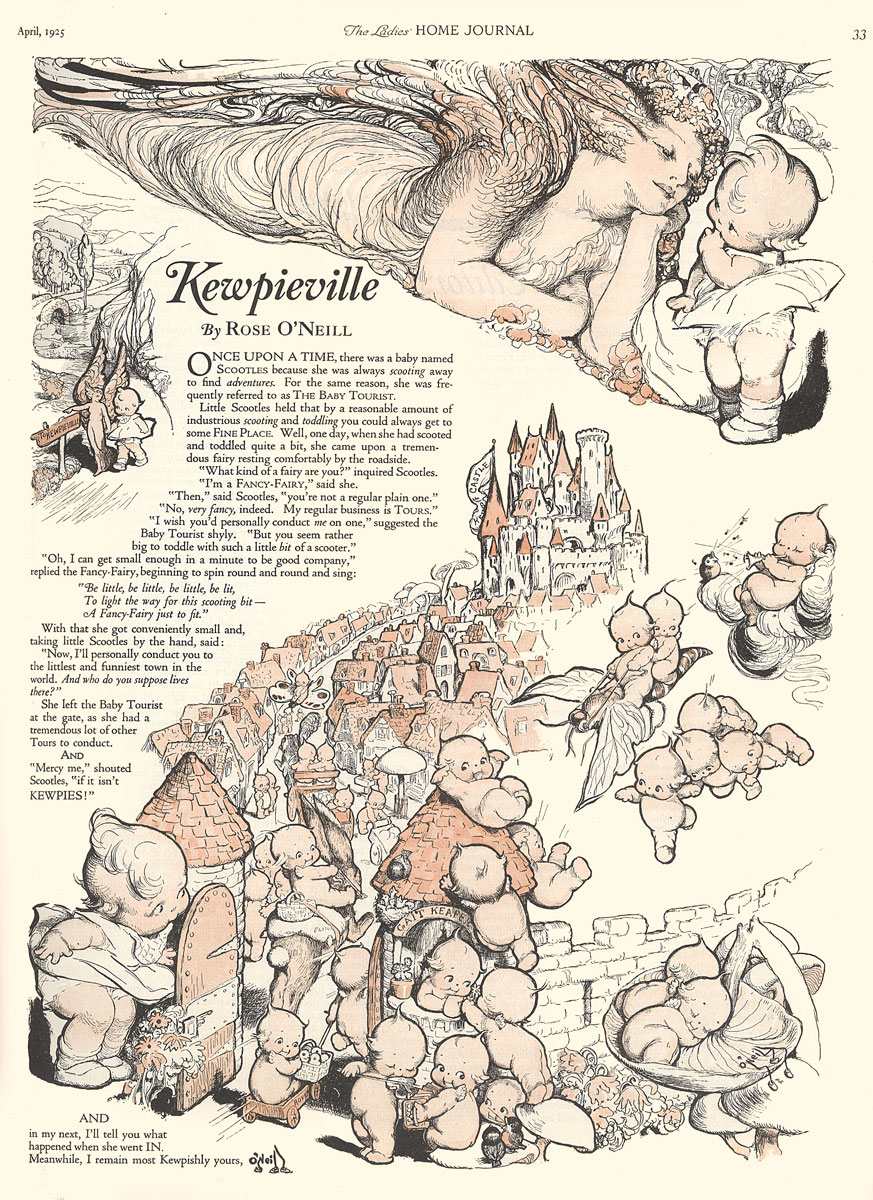

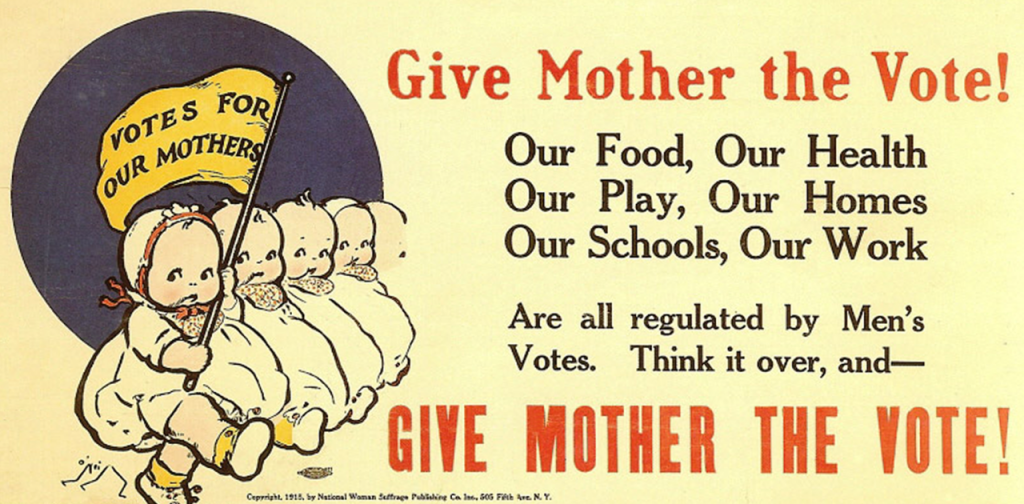

Despite limitations imposed upon women at the turn-of-the-century, faith in her craft and the firm belief that women weren’t meant to be silenced made Rose O’Neill arguably the first American woman cartoonist to be professionally published. During a time when editorial illustration was strictly a man’s business, the self-taught artist, women’s rights activist, and creator of the internationally recognizable cartoon cherub, Kewpie, would rise to fame and become one of the best known and highest paid female commercial artists at the turn of the 20th century.

Despite limitations imposed upon women at the turn-of-the-century, faith in her craft and the firm belief that women weren’t meant to be silenced made Rose O’Neill arguably the first American woman cartoonist to be professionally published. During a time when editorial illustration was strictly a man’s business, the self-taught artist, women’s rights activist, and creator of the internationally recognizable cartoon cherub, Kewpie, would rise to fame and become one of the best known and highest paid female commercial artists at the turn of the 20th century.

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in 1874, O’Neill had a fondness for illustration from an early age — a talent strongly supported and encouraged by her father. “Give me this child,” O’Neill recalls her father saying. “I want to make an experiment. Specialize. She shall have no studies except those conducive to the Arts”. Whether it be rendering images from her father’s library or doing portraits of family members, by the age of nineteen O’Neill had honed her skills as an illustrator and set out to seek professional work in New York City.

Equipped with only sixty illustrations in her portfolio, O’Neill’s work quickly gained the attention of esteemed male magazine editors and advertising executives despite her gender. By 1896, O’Neill produced over 700 cartoons and illustrations for the popular satire magazine Puck, and throughout her twenties, she amassed an incredibly large and diverse portfolio of commercial work and an equally impressive client list — a set of accomplishments few could claim, man or woman, in the world of illustration. A woman ahead of her time, “O’Neill’s appeal was due to a combination of her sense of humor and her romantic nature,” notes the Bonniebrook Gallery. “It didn’t hurt that she could work quickly and meet deadlines.”

Harper’s, Life, Broadway Life, Cosmopolitan, Collier’s, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and Women’s Home Companion were just a few of publications she contributed to, and her work for Kellogg’s Cornflakes, Jell-O, Edison Phonograph, and Rock Island Railroad could be seen in advertisements across the nation. It was the approximately 100 illustrations that she did for Jell-O from 1909 to 1922 and her own infamous cartoon creation, Kewpie, though, that would make O’Neill a household name and a conduit for women’s rights. Unlike so many of her fellow illustrators, “Rose’s output was prolific,” points out Bonniebrook. Never one to quit, O’Neill would continue to produce Kewpie comic strips up until her death in 1944.

O’Neill was an amazing illustrator and woman, both for her latent talent and progressive mindset. Against all odds she used her personal and professional drive to overcome gender biases and political restrictions in a society that saw women more as an accessory than contributor. A fervent activist for women’s rights, O’Neill used her artistic talents to campaign for the equality of women and minorities across the United States. There were countless articles in popular newspapers that told the story of the activist artist and “ardent suffragist.” Through her celebrity and art, O’Neill was able to speak for a population who up until this point didn’t have a voice. Her art amplified women’s rights messages in a way never before seen by the American public.

Her drive and how she used her art to fight for everyone’s right to political equality remains part of the legend of Rose O’Neill to this day. Countless illustrators have been inspired by O’Neill’s beautiful works, but she is also widely admired for the numerous doors she opened for women with her craft. Not one to simply standby and submit to policies that would stifle women’s voice, as Bonniebrook Gallery writes:

Rose O’Neill lived her life a liberated woman. She didn’t have to work at it. It came to her instinctively due to the confidence she had in her own abilities. She did, however, work at liberating others so they might choose how best to live their lives.

–by Caitlin McCabe

Dale Messick

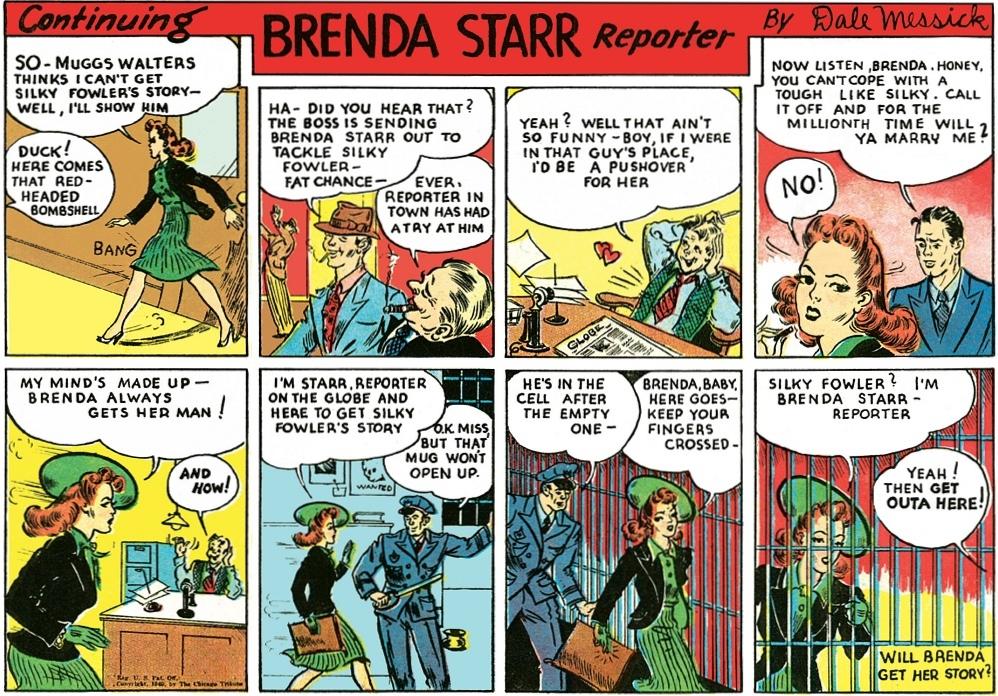

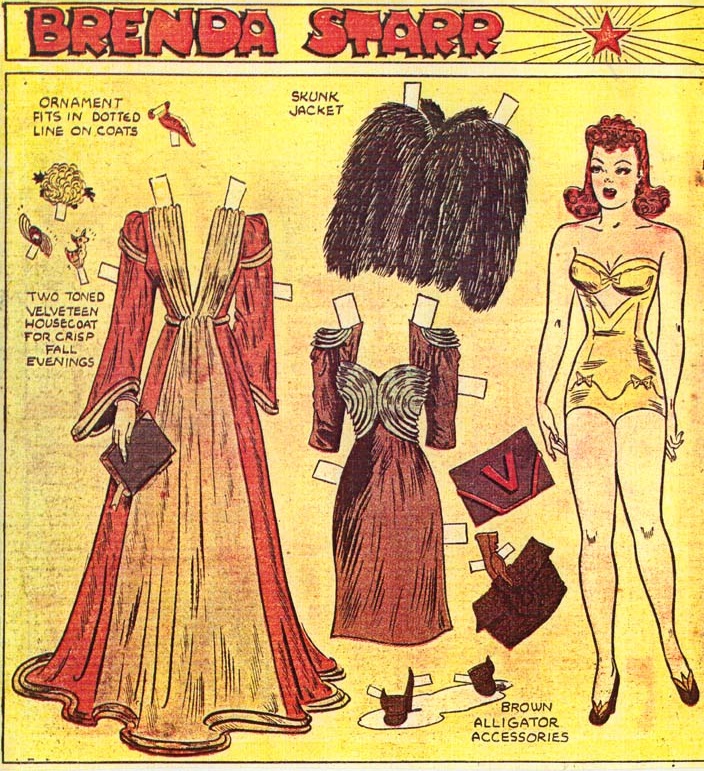

Throughout her life Dale Messick, the first nationally syndicated American woman cartoonist, expanded possibilities both for real women in her own profession and for fictional women in the comics pages. Messick’s jet-setting reporter Brenda Starr was an ambitious career woman when most of her female panel neighbors were housewives, and the creator herself blazed a trail for other women who came after her in the industry.

Throughout her life Dale Messick, the first nationally syndicated American woman cartoonist, expanded possibilities both for real women in her own profession and for fictional women in the comics pages. Messick’s jet-setting reporter Brenda Starr was an ambitious career woman when most of her female panel neighbors were housewives, and the creator herself blazed a trail for other women who came after her in the industry.

Dalia Messick was born in 1906 in South Bend, Indiana, the oldest of five children. Encouraged to develop her creative skills by her father, a sign painter and art teacher, and her mother, a milliner, she drew her first comic at 10 years old. After high school, she briefly attended the Ray Commercial Art School in Chicago during the Great Depression, but soon took a job drawing greeting cards to support her parents and younger brothers. Within a short time she shrewdly increased her salary from $10 a week to $35 by negotiating progressively higher rates at different companies, but she quit in 1934 after “one of her cards sold a bumper-crop of copies and she didn’t receive a bonus,” according to a 2000 profile in Animation World Magazine.

Messick then moved to New York City and found work at yet another greeting card company, still sending half of her $50-per-week salary back home. In the evenings she developed concepts and art for newspaper comic strips, which she then offered to various papers and syndicates without success. Suspecting that editors didn’t take her work seriously because of her sex, she began working under the name Dale during this period. In 1940 she finally sold Brenda Starr, Reporter to the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate, making her the first American woman creator of a nationally-syndicated comic strip.

Like her creator, the character Brenda Starr was ahead of her time. At the time, women in journalism were mostly relegated to the society pages and advice columns. The same had been true for Brenda, Messick said, but she was determined to break out of that mold: “she was already a reporter when the strip started, but she was sick and tired of covering nothing but ice-cream socials. She wanted a job with action, like the men reporters had.”

Brenda got that excitement and then some: At various times she parachuted out of a plane with no pilot, was hijacked by pirates on the high seas, and went undercover to join a girl gang, all while coiffed and dressed to the height of fashion. In fact, during Messick’s 40-year tenure on Brenda Starr, women journalists often complained of its complete inauthenticity, to which she cheerfully replied that no one would read the strip if it depicted the actual life of a reporter.

Messick and Brenda also sometimes pushed the boundaries of what was allowed in newspaper comics at the time. Brenda’s voluptuous figure and red hair were inspired by Rita Hayworth, but a Washington Post obituary of Messick recalled that whenever she “drew in cleavage or a navel, the syndicate would erase it. She was once banned in Boston after showing Brenda smoking a polka-dot cigar.” Even in post-Brenda semi-retirement, her strip Granny Glamour was reportedly rejected by AARP’s Modern Maturity magazine because the senior citizen characters were “too activist.” That weekly strip instead found a home in Oakmont Gardens, a magazine for the California retirement community where Messick was living by that time.

Messick drew Brenda Starr until 1980 and continued writing the storyline until 1983. The strip lived on until 2010 under two successive writer-artist teams, all women. At 92 years old in 1998, Messick received the National Cartoonists Society’s Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award, which she called “the greatest moment of my life.” She died in 2005 in California.

–by Maren Williams

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!