One of the more memorable book challenges that we covered last year came when the mother of a high school student in Issaquah, Washington pushed to have the graphic novel Mangaman removed from Issaquah High School’s library due to one panel showing pixelated genitals. We have recently learned via ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom that the book was retained after passing through a review committee, public forum, and the school board!

One of the more memorable book challenges that we covered last year came when the mother of a high school student in Issaquah, Washington pushed to have the graphic novel Mangaman removed from Issaquah High School’s library due to one panel showing pixelated genitals. We have recently learned via ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom that the book was retained after passing through a review committee, public forum, and the school board!

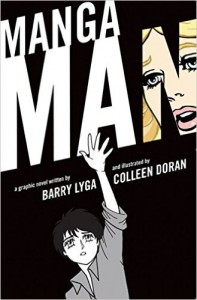

Mangaman was written by Barry Lyga and illustrated by Colleen Doran. It tells the story of Ryoko, a manga character who falls through a dimensional rift into a real-world American high school. The book received starred reviews from Kirkus (“an inventive offering, sure to please fans of both American and Japanese comics”) and School Library Journal (“a story full of clever humor and human emotions”), as well as praise from Bone creator Jeff Smith, who called it “an eye-popping fun-ride through the comics traditions of East and West.” All available reviews judge it to be appropriate for high-school-aged readers, while some even go a bit younger (12-13) in their recommendations.

In the clever metanarrative of Mangaman, Ryoko has trouble fitting in at his new school because he involuntarily brought with him various manga conventions: heart eyes when he develops a crush on the beautiful Marissa Montaigne, speed lines when he moves fast, and perhaps most embarrassing of all, pixelated genitals. On the page that parent Shirley Lopez flagged as objectionable, the nude Ryoko sheepishly cites Article 175 of Japan’s Criminal Code to assure Marissa that “it’s there, you just can’t see it.” In the next few panels both Ryoko and Marissa admit with relief that they are not yet ready to have sex anyway.

According to OIF blogger and longtime North Carolina school librarian April Dawkins, Mangaman was saved because the Issaquah School District scrupulously followed every step in its challenge policy. But due to imprecise language in the very first step, Dawkins argues that this book or any other in the district could theoretically be at risk of a unilateral ban if it happened to encounter an unsympathetic school administrator early on.

The problem, Dawkins says, lies in this first part of Issaquah’s reconsideration policy:

The complainant shall communicate the concern to the staff member(s) primarily responsible for the use of the materials. The two (2) parties shall make every effort to resolve the concern. The principal or department head may be involved at the request of either party.

Those of us who work in defense of intellectual freedom recommend that any school or library’s default position on a challenged book should be “innocent until proven guilty”–that is, it should not be removed based on the judgment of one or two people and should at least have the chance to be considered by a review committee. But all too often school administrators do not share that view and will even bypass existing policy to remove a book immediately when faced with an angry parent. As Dawkins points out, this policy as written would actually permit administrators to “resolve the concern” by doing exactly that.

While Issaquah handled this challenge admirably, the loophole spotted by Dawkins is just one example of why policies must be carefully crafted to make sure that they provide maximum protection for challenged books. Libraries and schools looking to hone their policies can get a jump-start with ALA’s Workbook for Selection Policy Writing!

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2017 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.