A year ago this week, the world mourned with the citizens of Paris, France, where a terrorist rampage that began at the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo resulted in the death of 17 people, including 12 at the Charlie offices. Cartoonists Charb, Cabu, Wolinski, Tignous, and Philippe Honoré were among the victims.

A year ago this week, the world mourned with the citizens of Paris, France, where a terrorist rampage that began at the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo resulted in the death of 17 people, including 12 at the Charlie offices. Cartoonists Charb, Cabu, Wolinski, Tignous, and Philippe Honoré were among the victims.

Did we take a stand against this terrorism? A lot of us did — we declared “Je Suis Charlie” (We Are Charlie), we shared Charlie‘s controversial cartoons, we shared our own cartoons in solidarity, and we decried attempts to stifle the creativity of satirists both in France and abroad.

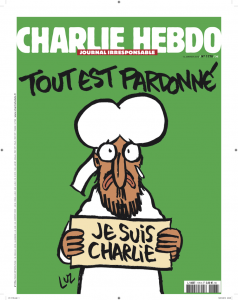

Just one week after the attacks, Charlie Hebdo released an issue that immediately sold out and was reprinted, putting millions of copies of the magazine in the hands of supporters around the world. The 42nd Angoulême International Comics Festival in France inaugurated the “Charlie Freedom of Speech” award and issued a special Grand Prix award, which were presented in honor of the cartoonists and editorial staff that lost their lives during the Charlie Hebdo attack. Malaysian cartoonist Zunar, who is Muslim himself and has faced constant censorship and harassment from the Malaysian government, called for a “World Cartoonist Day” in memory of those slain.

But instead of supporting the rights of those murdered, some questioned the editorial decisions of the Charlie staff, effectively blaming the victims for the terrible crime perpetrated against them. Renown cartoonist (and frequent target of censorship) Garry Trudeau argued that Charlie had crossed a line. Exhibits of Charlie‘s cartoons had difficulty finding a home, and universities canceled Charlie Hedbo events.

When PEN American Center decided to present its Freedom of Expression Courage Award to Charlie Hebdo staff, nearly 100 authors signed a statement opposed to PEN’s decision, and several authors withdrew from hosting the gala where the award would be presented. Some big names in comics stepped in to take their place: art spiegelman, Alison Bechdel, and Neil Gaiman took part in the event to show their support. Gaiman himself was schocked at the response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks, telling CBLDF’s Charles Brownstein:

The thing that fascinates me most about Charlie Hebdo in particular — which completely baffled me, took me by surprise — was it’s the first time I have ever seen not just the “we’re for free speech, but…” brigade coming out—the people who are like, “You know, yes, these people were massacred, but they were writing offensive things. They were drawing cartoons that people were offended by,” as if the correct response to being offended is to murder somebody.

Unfortunately, the attacks on Charlie Hedbo were only the beginning; 2015 proved to be a very rocky year for satirists. Cartoonists weren’t just facing down terrorists — several were persecuted by their own governments. Iranian cartoonist Atena Farghadani was sentenced to nearly 13 years in prison for a cartoon she drew mocking the debate over a draconian birth control bill in her home country. Cartoonist Zunar faces 43 years in prison over sedition charges that resulted from a tweet. A Lebanese comics collective had to turn to crowdfunding to stay solvent after the government fined its editors $60,000 for “inciting sectarian strife” and “denigrating religion” through comics. We learned that Syrian editorial cartoonist Akram Raslan likely died in 2013 after he was arrested for offending Assad regime.

Satire has a long tradition in France and in cartooning around the world. It has been used for centuries to comment on social ills, governmental oversteps, and religious zealotry, often in a way that is more accessible and more appealing to the general population of a community. But why has it been so difficult to learn the lessons of the Charlie Hebdo attacks? Why do many refuse to recognize that no one should be punished by their government or murdered by terrorists for making cartoons, even if we don’t like the images?

In a powerful essay commemorating the one-year anniversary of the attacks, Professor Karima Bennoune uses the response to PEN America to illustrate one of the many reasons why the negative response to the Charlie Hedbo attacks is so problematic:

[The authors] wanted to make clear that they were not Charlie. They claimed solidarity with Ahmed [Merabet, the French Muslim policeman killed outside Charlie‘s offices]. They presumed to know what the Ahmeds of the world think (and that they think alike) while overlooking the contemporary politics of the Muslim majority regions of the world. They regretted the killing, but clearly didn’t understand it.

The petition’s authors presumed a) that French Muslims were mostly devout, and b) that this meant they could not stomach satirical drawings — two huge and highly inaccurate presumptions. This was a recurring theme after 7 January — that all Muslims and all people of Muslim heritage were offended by the publication of cartoons (whether they liked the cartoons or not). It is not at all clear how assuming that 1.5 billion people have no sense of humor (and no politics) is anything other than patronizing.

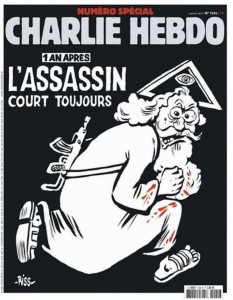

Charlie Hedbo‘s future isn’t guaranteed. Since the attacks, the magazine has faced a great deal of turmoil. The sudden influx of financial support has led to internal strife over how the magazine is run, some cartoonists and staffers have left, and some have questioned Charlie Hebdo‘s continued commitment to free expression. Even if Charlie‘s satire seems more subdued, the magazine remains defiant, putting out an issue every week. The cover of this week’s issue reads “One year on: The assassin is still out there,” reminding the world that free expression still isn’t safe.

Professor Bennoune echoes this sentiment in closing her essay:

So today, in memory of Charb, Cabu, Wolinksi, Tignous, Bernard Maris, Honoré, Elsa Cayat, Mustapha Ourad, Frédéric Boisseau, Michel Renaud, and the police officers Franck Brinsolaro and Ahmed Merabet who were killed exactly a year ago, and all those who died at the hands of Islamist terrorists in 2015, I say simply, “I am still Charlie.” It is a battle cry in the ongoing campaign against fundamentalist violence and the ideas that motivate it, which is one of the defining human rights struggles of 2016. That is perhaps the most important truth about Charlie.

As the Charlie Hebdo staff, France, and the world continue the grieving process, as we remember the cartoonists, editorial staff, police officers, and French citizens who lost their lives a year ago, we can only hope we start to embrace the lessons of Charlie Hebdo: that free expression should never be punished with murder and that no one deserves death for making a cartoon.

Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work in 2016 by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

Betsy Gomez is Editorial Director for CBLDF.